Over the years the British government has gradually, drastically, eroded the place of art in the classroom. It is a shift that has led to an ever-more elitist creative industry, populated by those whose parents could either afford private schooling or who could pass on their own experiences of working in such jobs to their kids. “It’s not that politicians don’t understand art education,” artist Bob & Roberta Smith told Digital Arts magazine, “but they’re so driven by the idea that they’ve got to get kids to do basic English, Maths and Science that it is taught to the exclusion of the arts.”

That exclusion affects all kids differently: access is thoroughly dependent on not just educational and socioeconomic factors, but on cultural background too. “My peers had to ‘discover’ graphic design; it’s not encouraged as degrees in law or medicine,” our editorial assistant and former Central Saint Martins student Anoushka Khandwala wrote in a piece for Creative Review. “The visibility of the design industry is a real problem not just in terms of outreach programmes, but in breaking down ideas about what a creative career can be and what a stable profession is. We need to destroy stereotypes that put parents off ‘allowing’ their children to follow careers in design and instead educate families to encourage it.”

Where schools are failing, could galleries be the ones to step in? I began to reflect on the community-based role of the gallery after visiting the thought-provoking Whitechapel Gallery exhibition, Exercising Freedom: Encounters with Art, Artists and Communities, which documents the gallery’s education programme from 1979-89. This was a challenging time for art: after Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in June 1979, the new Conservative government’s first spending review cut off £1 million to the arts.

“Access to the arts is thoroughly dependent on not just educational and socioeconomic factors, but on cultural background too”

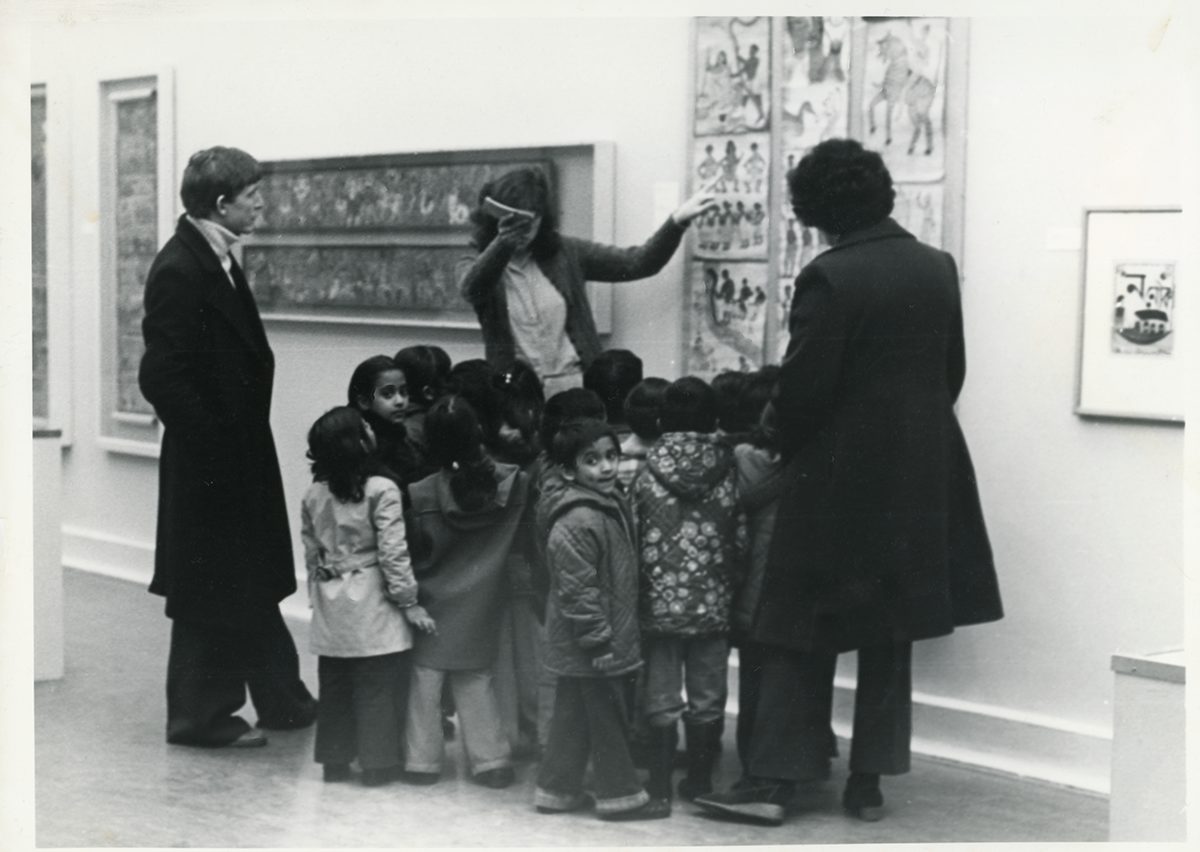

Whitechapel Gallery was one of the first UK publicly funded art galleries to formally create an education department in the late 1970s, but what makes the exhibition so compelling is the specific targeting of their work towards the local community in Tower Hamlets, East London. Thanks to its location right next to the affluence and banking hubs in the City of London, the borough displays startling discrepancies of wealth. It is a richly diverse area, with significant economic deprivation, then and now; as of 2020, 132 different languages are spoken in schools, and it has the second highest levels of hate crime in London.

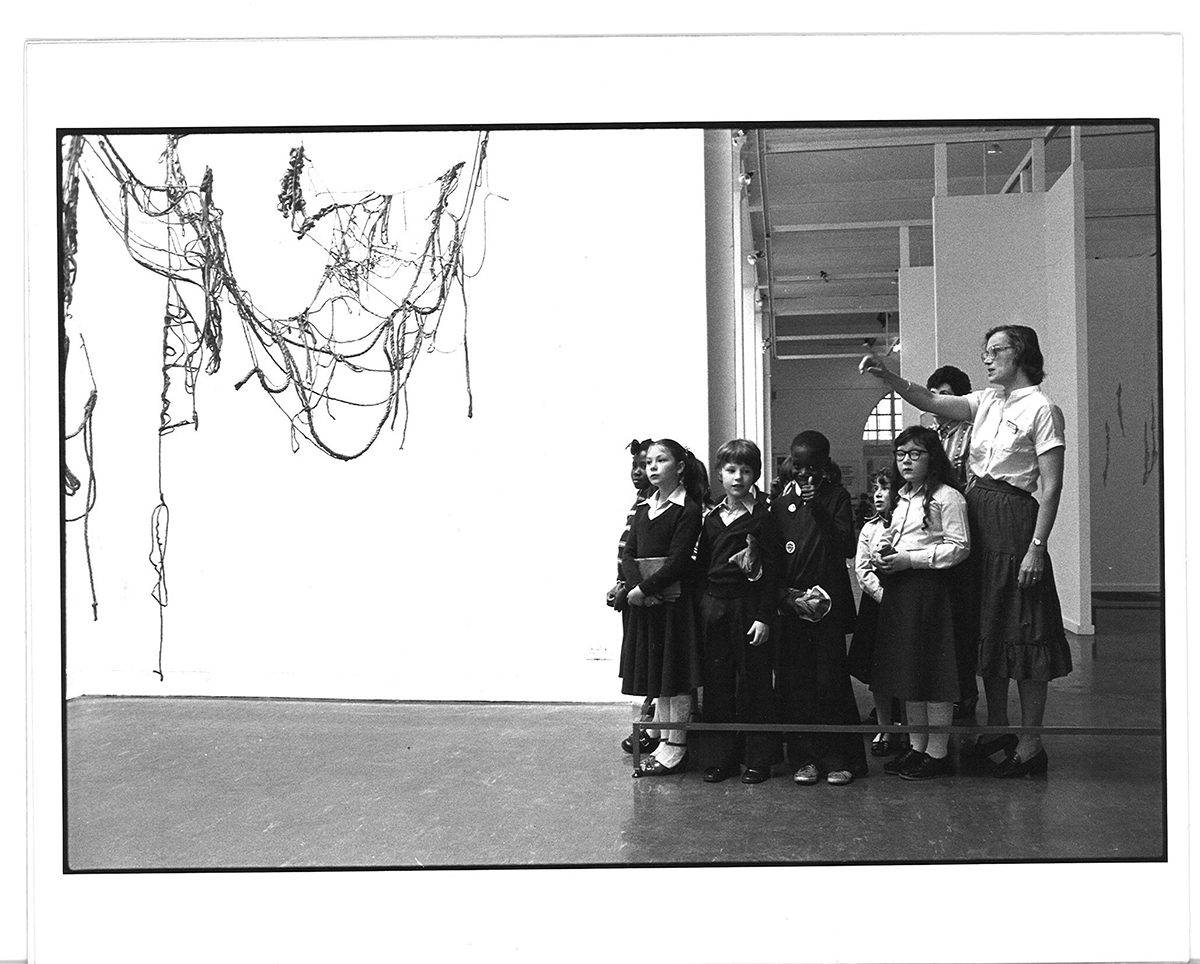

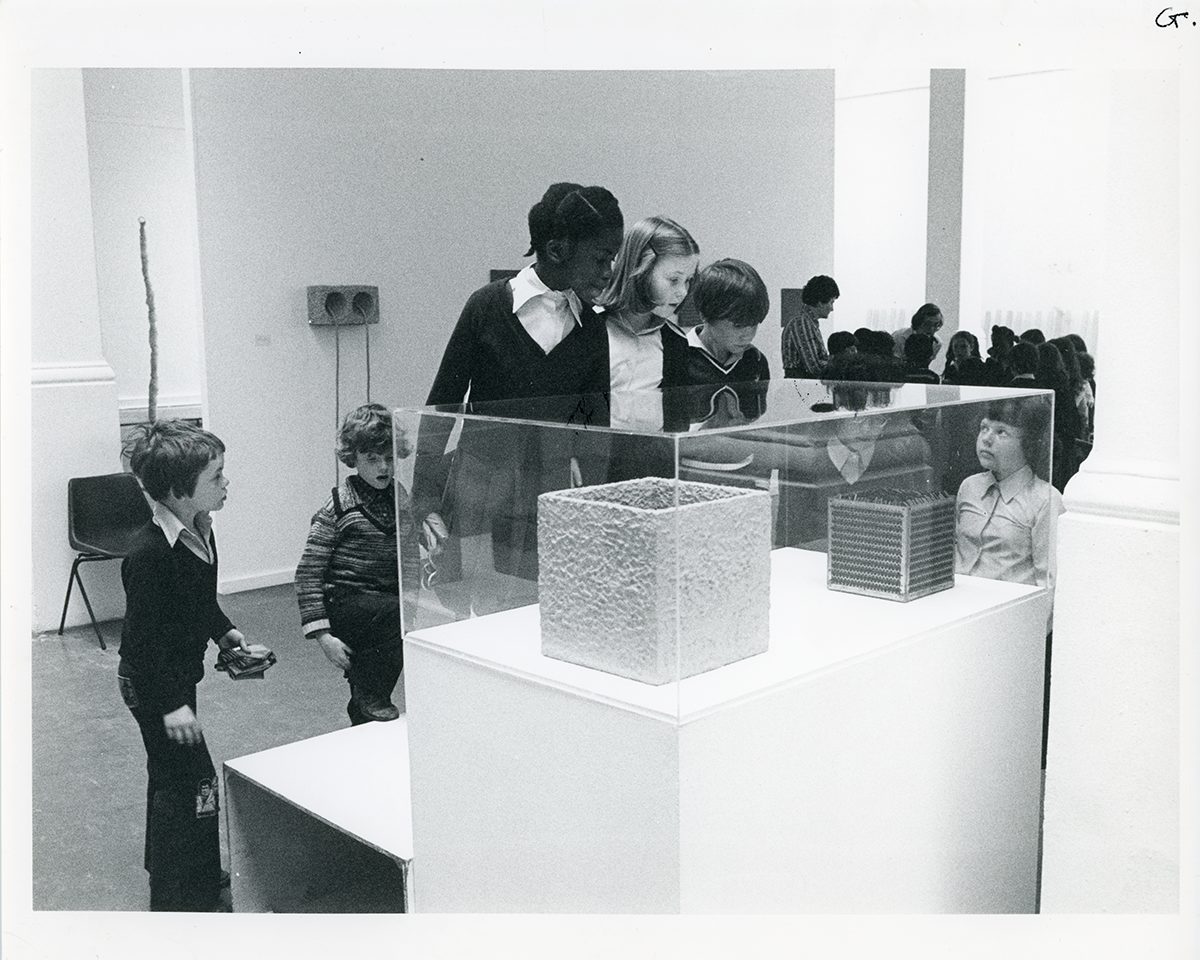

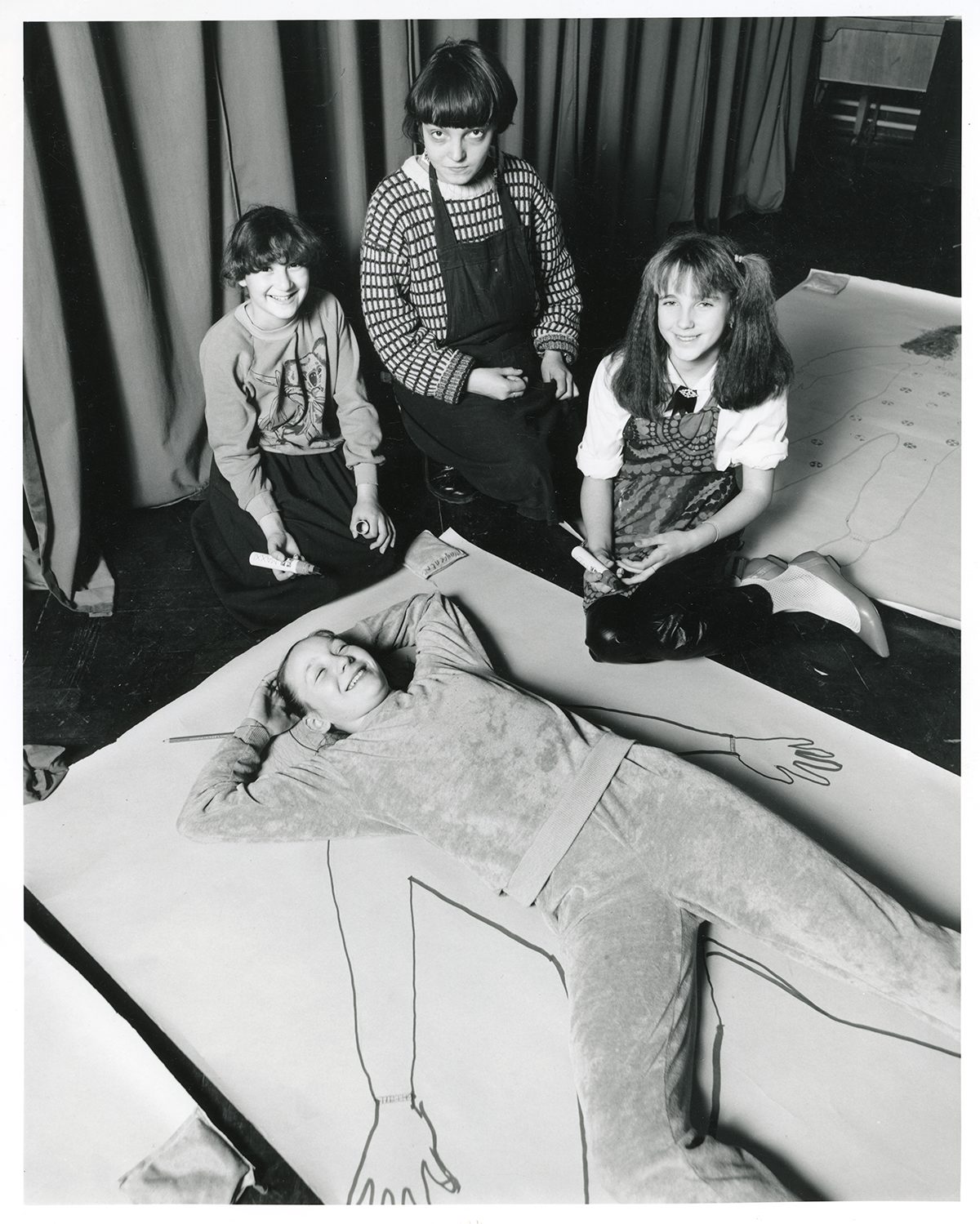

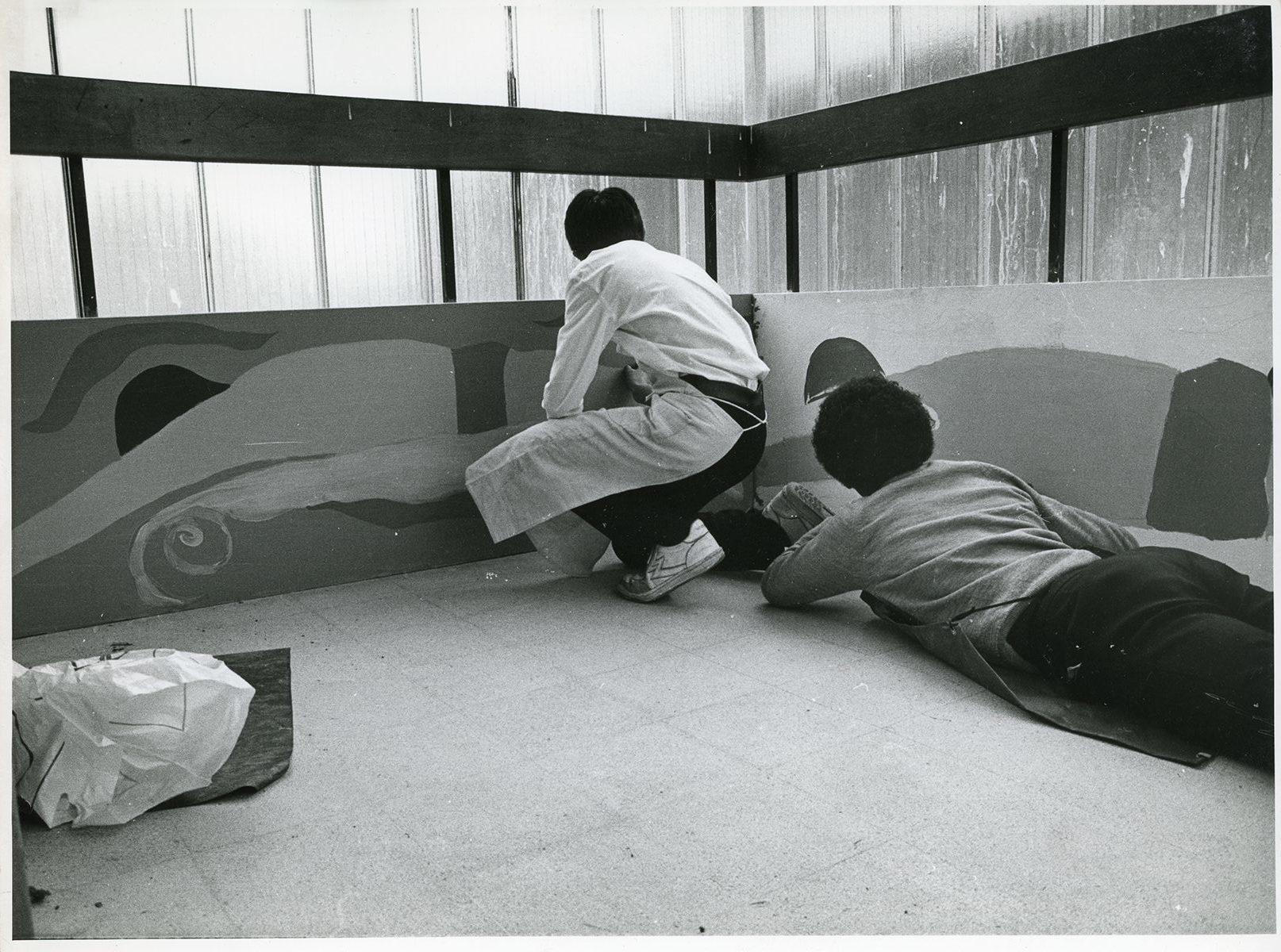

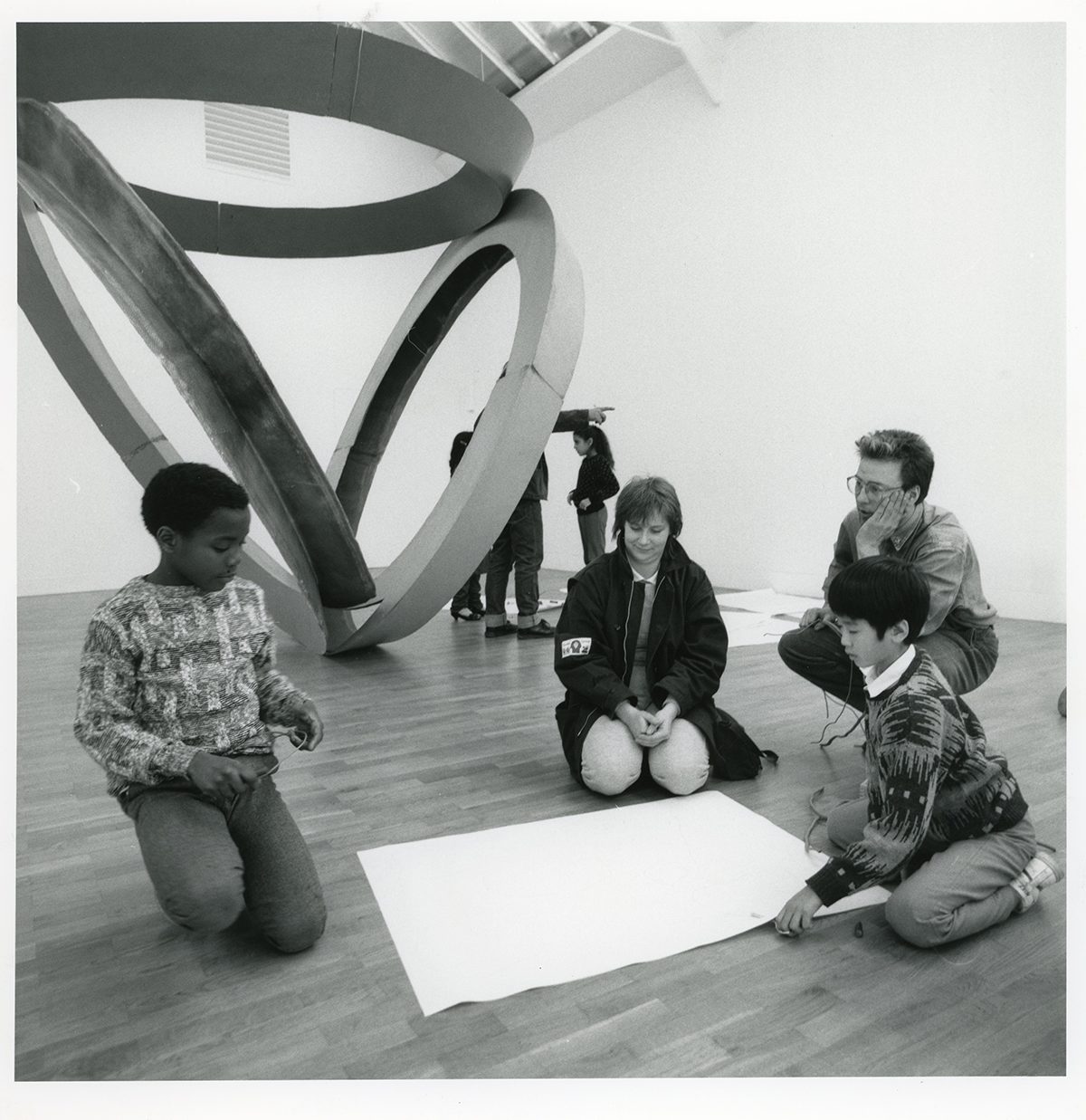

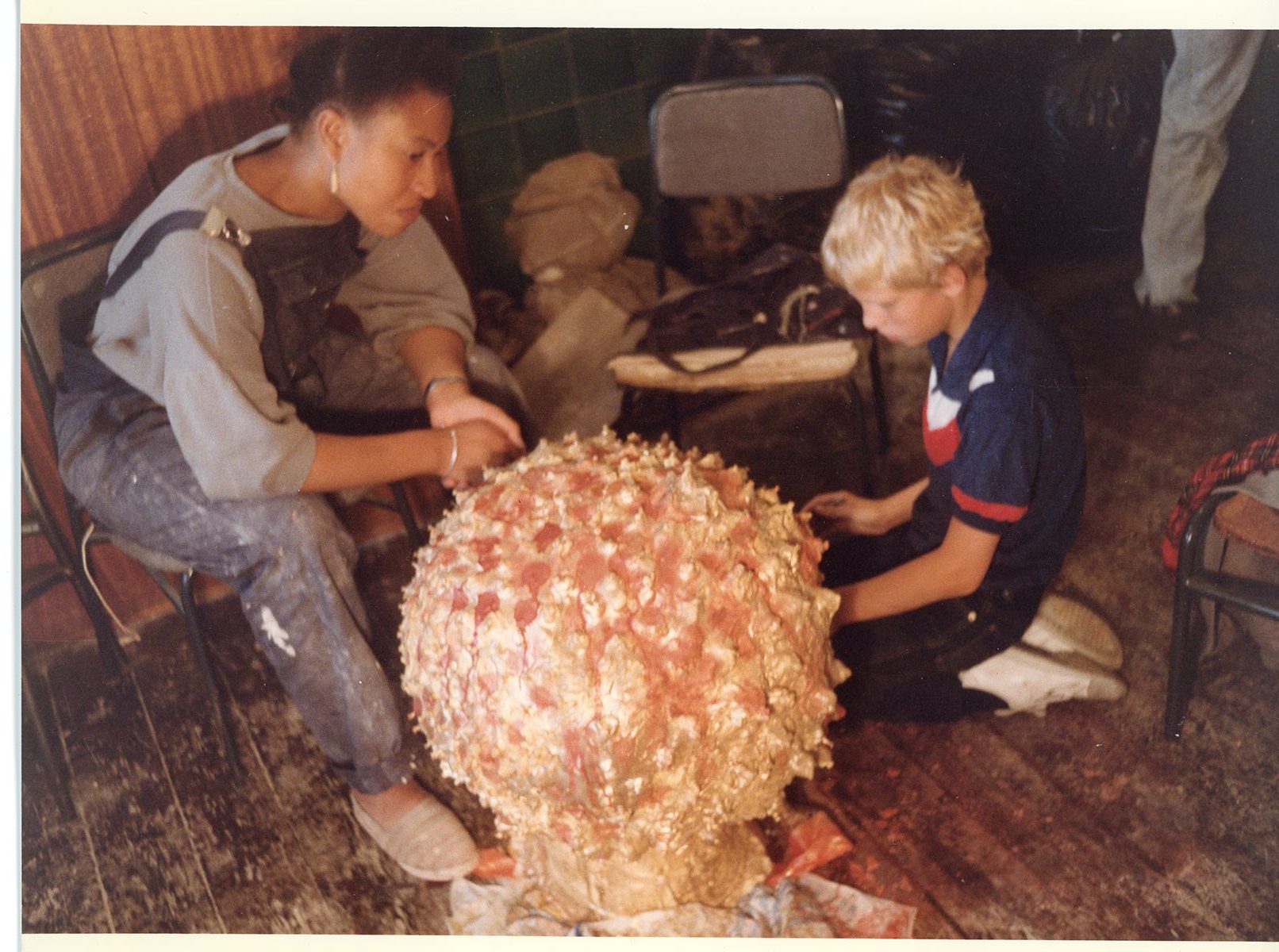

In the early 1980s, the area’s many empty warehouses began to attract artists, and organisations like Acme and Space encouraged them to live and work there—an initiative that Whitechapel Gallery took advantage of in its pioneering approach to working with local schools and artists and promoting collaborative learning. This was spearheaded by Jenni Lomax, the community education organiser from 1979-89. At the heart of her approach were educational activities with artists both on and offsite, with artists encouraged to bring elements of their own practice, conceptual premise and working processes into the projects.

Lomax describes the gallery as a “conduit” that brought artists and schools together; facilitating activities, exhibition-based learning and visits to local artists’ studios. Pupils were given the chance to see a bigger picture of what artists really did, and what art meant: they could see that they were working in the very same area that they called home, how they worked, and where art came from. Another of the Whitechapel’s priorities was working with children who had special educational needs, and for whom English wasn’t their first language. Lomax says that the very “physical”, “immediate” and “direct” approach they took meant that “there wasn’t a distinction between those who had the intellectual knowledge of art, and those who didn’t.”

These sort of priorities—giving pupils direct access to working artists; democratic teaching approaches; inclusivity for those who might not usually be able to access art; a focus on artists local to the schools and the institution—are as relevant today as they were in the late 70s. But which institutions’ education programmes are still pushing them?

“Pupils were given the chance to see a bigger picture of what artists really did, and what art meant”

Shepherd Manyika is well placed to ask: he’s an artist and BA Fine Art teacher, and one who himself entered his creative practice through an outreach programme, Central Saint Martins’ Insight. He arrived in South London at the age of 12 from Malawi, and was always “obsessively” drawing as a kid. “Everything that I did good in at school was to do with the arts. So for me, it just made sense to go into something similar. But obviously, parents have a different path for you,” he says, explaining that his mother was set on him pursuing architecture.

Khandwala, who now works with Manyika as a teacher on the Insight programme, argues that the full breadth of careers available in the arts is rarely visible to those outside of it, which can be a particular problem for those who lack role models or other guidance. “We have to work with cultural pressures, as so many parents think that architecture is a steady job, for instance, but [their child] might be better suited to, say, jewellery design or product design,” she says. “Accessibility is one thing; visibility is another thing entirely.” The cliché “you can’t be what you can’t see” exists for a reason.

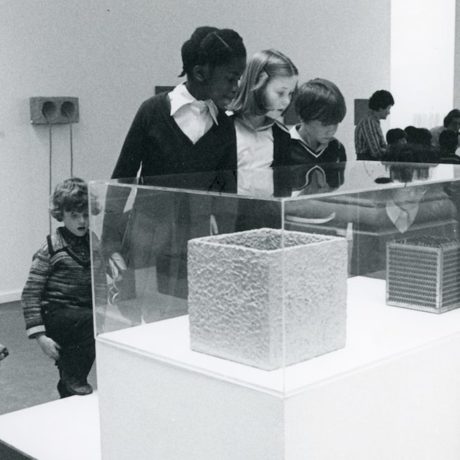

- Left: School groups at the Eva Hesse exhibition, 4 May – 17 June 1979, Whitechapel Gallery. C/o Whitechapel Gallery Archive. Centre: Primary school children led by Jenni Lomax on a tour of the exhibition Arts of Bengal, 9 November – 30 December 1979, Whitechapel Gallery. Whitechapel Gallery Archive. Right: School groups at the Eva Hesse exhibition, 4 May – 17 June 1979, Whitechapel Gallery. © Whitechapel Gallery Archive.

Even beyond the role of art in the curriculum, the current doctrine of the British government often appears to actively promote the fallacy that the arts are inherently frivolous. We should all really just do something sensible, their communications seem to suggest. Last year, a controversial advert advised those working in the arts to be a bit more like “Fatima”, hang up our metaphorical ballet shoes and “get into cyber” instead. These sort of messages put forward the suggestion that creative roles are somehow invalid. “When those young people come to applying for university or thinking about their future,” says Manyika, “they’ve been conditioned into thinking that there’s nothing for them within that industry, and no money.”

Schools need to demonstrate the opportunities that art can offer, especially for those kids who don’t have the privilege of parents with “cultural capital,” as he puts it. “They might be drawing things from animé, or trying to replicate what Virgil Abloh is doing, but if interaction with visual culture is lacking in their everyday life, they’re not really seeing the value in it.” Manyika has worked with institutions including Camden Arts Centre, Tate and South London Gallery. The latter takes an original approach, allowing young people themselves decide what they’ll be working on, and with which artists.

“Young people have been conditioned into thinking that there’s nothing for them within the arts, and no money”

For the outreach programmes of arts institutions and galleries to succeed, more joined-up thinking is needed: curatorial, PR and educational departments should not be seen as discrete units, for instance, but inextricably connected. Are they currently doing enough and reaching the people they should? “I think it depends on who you’re working with,” says Manyika. “Each individual gallery will always have an education department, regardless of whether they are interested in it or not, because that’s how they make their funding—it looks at how you’re engaging with the community.”

As such, while Manyika reports numerous positive experiences working with institutions on educational programmes, he points to a frustrating amount of red tape, and a worrying tendency to overlook individual experience. “Everyone that comes through is a number—it might be, ‘Today we engaged with 30 Black kids.’ I think it’s really quite troubling.”

Such box-ticking fails to fundamentally address the institutional racism that many have highlighted in the art world. This was brought into sharp focus last summer during the Black Lives Matter protests, which prompted many public-facing bodies to pledge changes. It now remains to be seen just how resolutely they will stick to their promises.

“What institutions need to do in the long term is to really think about representation and why representation matters”

For any institutional educational programme to bring about real change, it needs to be genuinely inclusive. It’s about what’s on the walls, who they’re showing, who’s delivering programmes, and what they’re communicating in written and visual messaging. It’s about how they structure their teams, curate their shows and programme their outreach. One community arts programmer, who has organised workshops for up to 2000 children at the Tate and wished to remain anonymous, argues, “What institutions actually need to do in the long term is to really think about representation and why representation matters.”

This means more than just meeting “quotas”, they add, but considering race, class, disability, sex, gender, neurodiversity and more on a more individual level.

Gallery outreach programmes could learn a lot from Whitechapel Gallery’s early approach. “If the organisation lost its preconceptions about gallery education, [it] could feed into the programme that made the life of the gallery richer and the life of the community richer,” as photographer Zarina Bhimji, a 1989 artist in residence, put it. Bhimji’s approach to teaching also bears repeating: “I wanted them to be an artist. They hadn’t imagined that that could be their thing, that they could be an artist.” She invited kids to reflect on broad issues, like defining creativity, as well as thinking about the personal, such as their experiences of racism in their local authority estate. “It was also making them feel confident about themselves and their place in the world… being an artist is interconnected to properly feeling that you can take that space.”

Exercising Freedom: Encounters with Art, Artists and Communities

At Whitechapel Gallery 7 October 2020 to 21 March 2021 (new dates to be confirmed)

VISIT WEBSITE