The environment in which we encounter art is often as important as the artwork itself. In 2011, Marcelle Joseph, a curator and collector, began to look for alternative spaces to present art: she organized pop-ups in Shoreditch and a sculpture show in a park in Surrey.

“After those shows, I decided that a turn to the domestic was necessary. I thought that it would appeal to artists to see their work displayed in the place where much of their output ultimately lives, as well as to contemporary art aficionados and novice collectors who might be intimidated by the often rarefied air one breathes at white-cube galleries.”

“I find it increasingly difficult to acquire artworks by artists that I have never met”

Joseph lives in Ascot, thirty miles from London, a leafy suburban area known for the races. Her generous house and garden were the perfect setting for a show: a salon-style group exhibition with indoor and outdoor performances, an artist DJ and poetry readings on the opening night, completed by a taco truck and a speciality cocktail—designed to “attract people from London as well as the local area”. Guests were invited to wander through almost all of Joseph’s home to see artworks, the comfortable setting also allowing potential buyers to “envision how an artwork may look in their own domestic setting”.

The formula worked, and Joseph went on to run four exhibitions at home—more than 200 people showed up for the most recent one, and more than 125 artists have been shown at home, including Victoria Sin, Colden Drystone and Bea Bonafini

. There has even been Turkish cuisine prepared by Jonathan Trayte. According to Joseph “the last train back to London from Ascot is quite raucous, I hear!”

The homely environment is not only a commercial gimmick in Joseph’s case: most of the artists she works with as part of her roving curatorial platform are people she knows and collects herself. “I find it increasingly difficult to acquire artworks by artists that I have never met. The relationships I have made with artists somehow feed into the narrative of the artworks I have collected.

“My favourite pieces are often some of the most recent artworks I have acquired, including three artworks from this year’s graduate degree shows by Gray Wielebinski (Slade MFA), Alexi Marshall (Slade BFA) and Beatrice Lettice Boyle (RCA). Ceramics has been a recent focus of my collecting and curatorial activities. I will curate a two-person show at the Hannah Barry in November, featuring the work of two ceramic artists, Lindsey Mendick and Paloma Proudfoot.”

Rebecca Fairman is the director of ArtHouse1, located on the top floor of “my beautiful big old house in Bermondsey”, a few minutes’ walk from the ultimate white cube: White Cube. For years, the space served as Fairman’s graphic design studio, but in 2013 she decided to repurpose it as an exhibition venue, organizing sporadic shows every year, at first. “It was such an amazing experience for me, the artists, colleagues, friends and neighbours, that I decided to take some time out to research the market, other possibilities and artists.”

Rather than considering it a commercial enterprise, Fairman says, “I see myself as an artist, offering other artists and curators the space and opportunity to develop and push their own boundaries.” The atmosphere of exhibiting in a private home encourages an open relationship and builds a network with other like-minded individuals—bypassing the formalities of the commercial white cube. “The benefits for myself are very small in terms of remuneration, but huge in terms of the buzz I get from supporting and helping others.” Fairman reflects. “It’s a unique, intimate, humble and welcoming space, with an amazing serenity that surrounds it.”

When visitors step through the door, however, there can be a bit of initial trepidation, Fairman notes. “New visitors enter with a little nervous hesitation to start with. However, by the time they have climbed two staircases with me up to the gallery, all hesitation has melted and turned into a magnificent grin.”

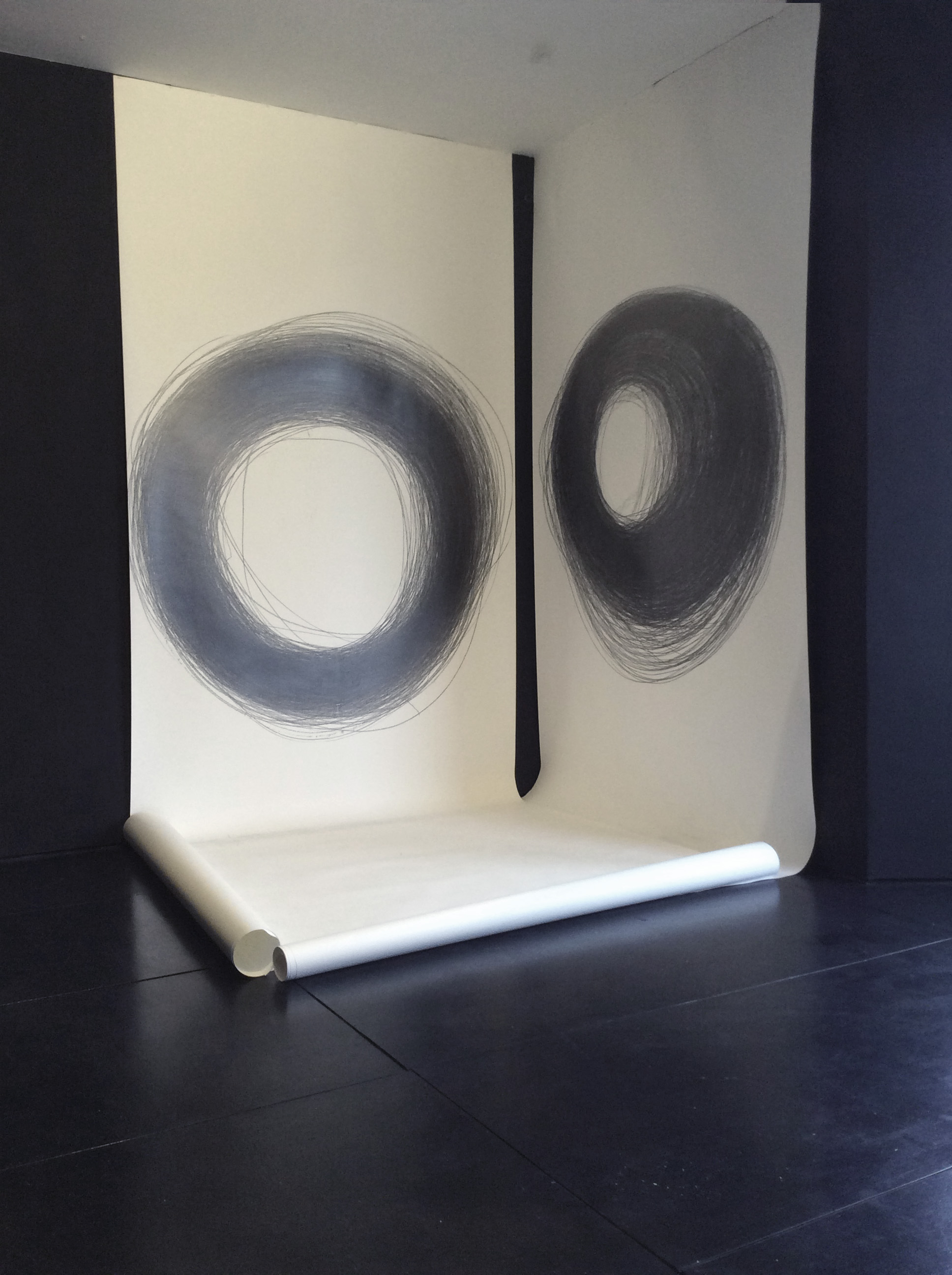

Her 700 square foot gallery space still feels domestic: white walls and waxed wooden floors, also painted white, with original Georgian fireplaces and windows dotted all over give the room a cosy and light feel. “Some of the very best exhibitions have used the domestic architecture to enhance their works in incredibly skilful and unusual ways,” Fairman recalls. “I think the space allows work to be viewed and considered on a more intimate level, on a scale that people can relate to.”

The ambience couldn’t be more different from the neighbours’, with its conventional, cavernous, impersonal interiors and black-clothed staff. This has a discernable effect, Fairman feels, on the way visitors feel they’re able to interact with and respond to the art. “There are no placards or signs to regulate or rule. Every visitor gets a personal tour here, and a cup of tea should they wish.”

Walk down Evelyn Street from Surrey Quays station towards Deptford, and you will find the Agency gallery, which stands out with its black, somewhat ominous, front. Ring the bell here, and Beatrix Gassman de Sousa, director and founder, will most likely let you in, most likely also dressed in black—but here the similarity with a traditional gallery ends. Once you are over the threshold you feel at home among the artworks; an installation might dramatically fill the living room in front of the bay windows; a video work might play in the dining room. Gassman de Sousa’s personal effects have been moved out, but she very much lives here, with her wife—their own spaces are cleverly concealed, so they can have privacy when needed.

Gassman de Sousa bought the house at 66 Evelyn Street in the nineties when the area was still impoverished. “Then I used it as a casual project space with friends who I was sharing with for a year. The name of the project, the Agency, reflected its collective spirit at the time.”

Among the earliest shows were projects with friends of the collective and a joint show with a very young Rebecca Warren and the writer Fergal Stapleton. “The house was not designed as a gallery, but I guess it comes with the job that any house-space you imagine becomes quite gallery-like by default. I personally worked out a warehouse-style open-plan concept because the house was fairly derelict when I took it over and it had lost most of its original Victorian features.”

“The architect who worked the ideas into a proper design was Anand Zenz, an interesting maverick who at the time had designed one half of the first Wagamama restaurant. (The other half of the restaurant was designed by Ron Arad.) I loved the bare concrete style mixed with attitude and irreverence. I enjoyed working with an architect who did not design houses but industrial and commercial spaces. Today the house part and the gallery part are evolving creatively in dialogue with my partner and the artists.”

“It was my mantra not to cover up the quirky character of the space, but to offer artists the opportunity to work with it”

When converting her home into a gallery, certain elements were paramount in the design. “My priority has always been to maximize space and light, so we opened up the existing space, but the best thing was to go for extra height and light in the extension by creating a Victorianish dome with wood and honeycomb plastic rather than some slick glass extension.” Just as important, she says, was to build an energy efficient house with low-cost materials.

“It was my mantra not to cover up the quirky character of the space, but to offer artists the opportunity to work with it. In fact, it was a conceptual nineties thing to critique the museum and the white cube. So, the artists and I used to dream up ways to express the critique through the institutional architecture. At some point, I even wanted to build in a slanting floor and ramps instead of stairs, but that ended up breaking the budget, so it remained a dream.”

“People stay and engage strongly rather than to just dip their feet in”

Gassman de Sousa, like Fairman, notes that visitors also interact differently with the artwork in this type of setting, spending longer looking at the art and talking. Pushing the boundaries towards more political and problematic work is also possible in a private setting, as “people stay and engage strongly rather than to just dip their feet in. It feels like people respect the hospitality and effort more in a private salon-style setting.”

At first, Gassman de Sousa didn’t live in the gallery, but in the wake of the financial crash in 2008 it seemed like a sage decision, and “challenging art needs a safe space from capitalist constraints, so it can evolve in the first place.” That pragmatic decision was symbiotic with Gassman de Sousa’s political stance. “Independent galleries need to offer the space to experiment, evolve and to work in culturally progressive ways. The artist and the gallery need to be free from unreasonable commercial constraints to grow.”