E. Jane spent years researching Black femme performers. Their alter ego MHYSA continues to channel their archive with her third album.

E. Jane is a world-builder who contains multitudes, including their underground pop star alter ego MHYSA.

Their universe is technicolour and rhythmic: luminescent pink and lavender hues set to a soundtrack of vocal powerhouses. It is steeped in past and present history, filtered through fantasy that, when you spend enough time with it, eventually gives way to a softer, more empathetic future that centres the inner lives of Black women.

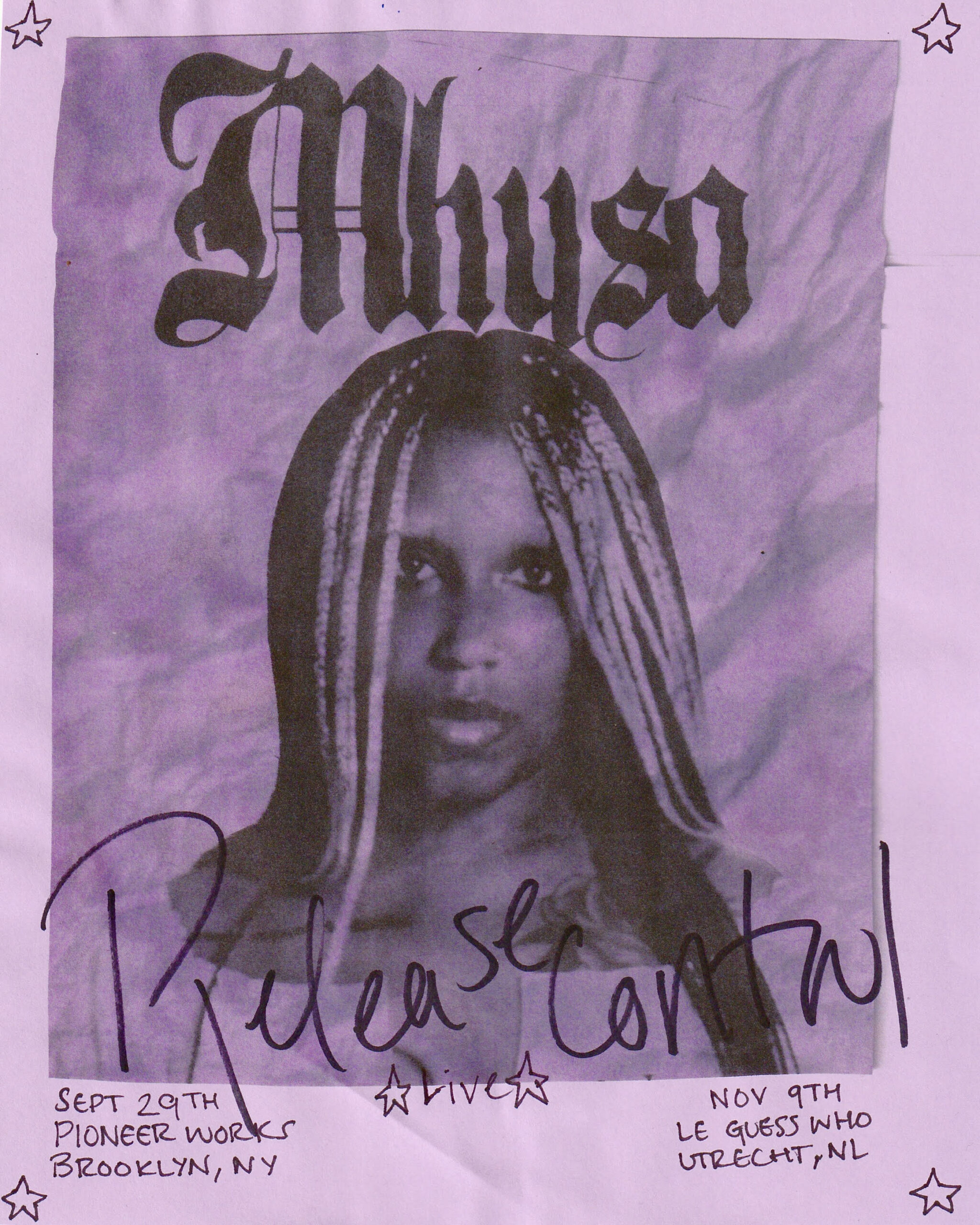

While the New York-based multidisciplinary artist’s work is research-based and built upon countless hours of footage of iconic divas, Jane grounds the concept in MHYSA’s physical performance and moving soundscapes. The musician’s third album, “Release Control,” a synthesis of Southern rap, experimental pop, R&B, and ambient electronic music, comes out on October 6.

“I’m putting my body on the line. I’m not just judging these women from afar. I want to see how hard it is.”

“I’m putting my body on the line. I’m not just judging these women from afar. I want to see how hard it is,” Jane emphasises. “Studying the labour of Black women is a big part of my practice.”

The term diva originated in the nineteenth century to describe the lead female singer in opera (there was also the divo for men), Jane explains. Now, the word is often associated with a misogynistic, negative connotation: a woman, often Black, whose ambition and self-worth overshadow her talent. Today, the term’s colloquial use, they suggest, tells us more about America’s limited understanding of what a successful Black woman should deserve and strive for.

Jane is reclaiming what it means to be a diva through their art, while MHYSA serves as a conductor of sorts. She is a student of the divas that Jane has studied: Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, and Beyonce. MHYSA is the embodiment of Jane’s practice, and she is constantly evolving, leaving a trail of her genesis online and through Jane’s work.

While MHYSA is grounded in the present, Jane is an archivist of Black divas across time. They are a new voice in Afrofuturism.

Jane’s four-dimensional work often creates a dialogue between the countless Black women who have blazed the trail for a new generation of performers like MHYSA. They place performances and video essays in immersive yet decluttered installations: subjects’ names have been painted on walls, photos printed on fabric and hung from the ceiling, monitors placed on the floor like giant iPhones and soft seats planted in front of projections.

In the case of Jane’s installation last year, “Where there’s love overflowing,” at New York venue the Kitchen, visitors took turns standing inside a shimmering, pink tulle bag to watch a recording of MHYSA’s live-streamed performance “When I Think of Home, I Think of a Bag.” (She originally sang the cover of “Home” from The Wiz from inside the same bag at Canada Gallery.) At the show’s closing night, MHYSA performed the song with a full band for the first time.

“Now, the word diva is often associated with a misogynistic, negative connotation: a woman, often Black, whose ambition and self-worth overshadows her talent.”

With Jane’s first solo museum show at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, “Drenched in Light,” underway, MHYSA — their persona they have been developing for nearly a decade — is entering a new era. The reintroduction of MHYSA will take place at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn on September 29 with a live set featuring all-new music. The show is the second event in the series HERETICS, curated by writer Jane Ursula Harris, which features artists who combine performance art and music.

“When I think of MHYSA, I think of the term Gesamtkunstwerk, the total art of everything,” they say. “I’m deciding the cover art, I’m playing with merch, and the promo images. It’s all in-house right now,” adding that this also includes the tradition of working with collaborators to bring their vision to life: in this case, Dreamcrusher did the album design.

Going on tour as MHYSA opened up Jane’s eyes to the level of work expected from performers. “The language that agents use made me think a lot about the relationship between America’s colonial past and music,” they say. “There’s still language that agents use, words like buying talent, that are really nefarious to me.”

They cite writer Robyn Crawford’s memoir about her friendship with Whitney Houston and Claudia Jones’s essay “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman” as key texts in understanding the expectations of Black female performers. “What could we do to be better as a world? What would it look like?” they ask.

“In a state where Black people are expected to be hypervisible, the right to hide when you want is already a utopian demand. How do we refuse that surveillance? How do we play with that surveillance?”

At Boston MFA, pages of Jane’s “Diva Zine” expand onto the walls. Excerpts from Zora Neale Hurston’s writing are collaged with found images from Jane’s archive. In the middle of the room, a set of three large, round floor cushions face a wall with a projection of their video essay “LetMEbeaWomanTM.mp4,” 2020. The video begins with a glitchy black and white clip of Diahann Carroll accepting a Tony Award for Best Lead Actress for her performance in “No Strings.” Carroll made history as the first Black woman to win in that category.

“I wanted this. I really wanted this,” she says, as purple sparkles scatter across the screen as Summer Walker softly croons, “and you let me be a woman.”

Here, the notion of the diva is deconstructed, unearthing the corners of a collective psyche so often ignored or whitewashed by popular culture. Jane shows the labour that it takes to keep up the persona of divadom. They show divas present and past, like Summer Walker and Diahann Carroll, in a nonlinear dialogue, striving and excelling — tired and frustrated — as an emblem of

the American dream built on the back of slavery and Black creativity and memorialized on the

Internet in digital clips.

The divas on screen are nuanced in their ambition. “They’re having conversations through time,” says Jane. “I’m really trying to point at how these issues are persisting today.”

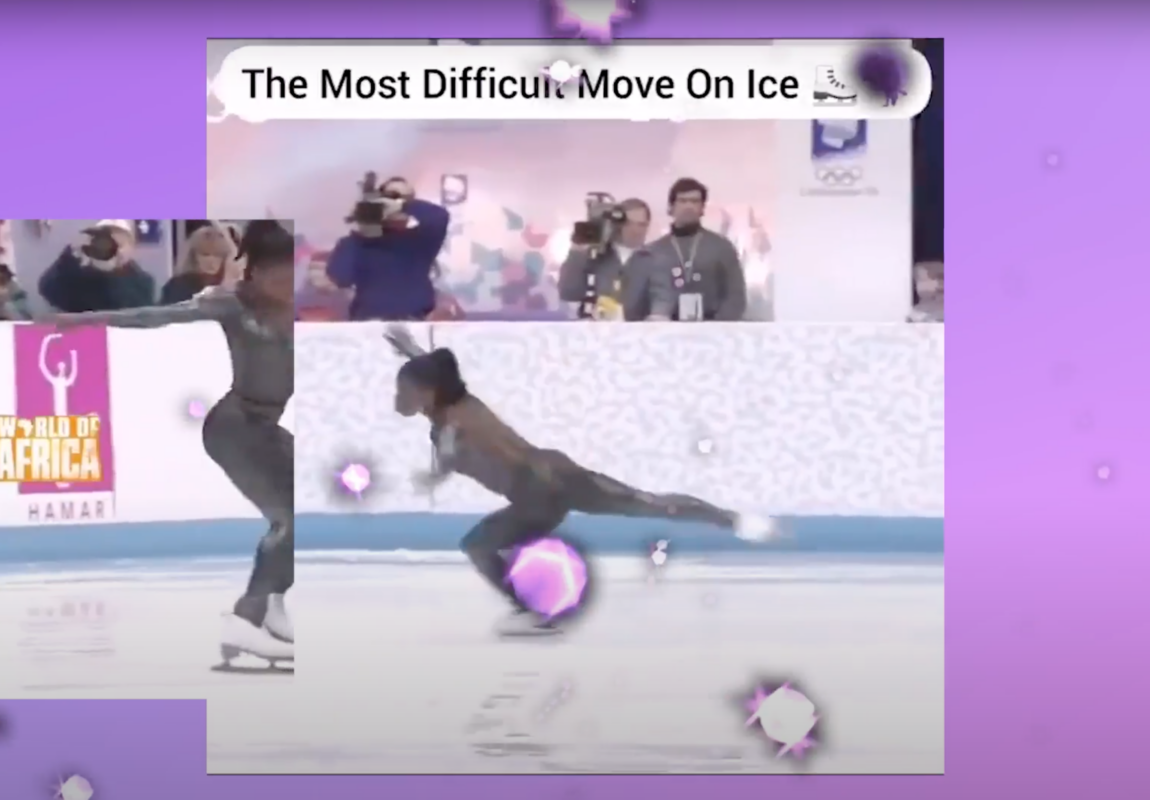

French Olympic figure skater Surya Bonaly appears on screen, completing, as subtitles written by a Twitter user tell us, the hardest move on ice. “It is interesting because that footage is old, but they are making it new again on Twitter by adding emojis, by adding text, by re-contextualizing it,” says Jane, adding that the larger story is that the move was also illegal.

“That was a move that disqualified her,” they tell me. “She did that because she could never win first place, even though she was super talented and could do things that your body is not necessarily able to do. She was like, well, let me show you what I can do since I’m not going to win anyway.”

As Bonaly spins on the screen, the unrealistic expectations and public scrutiny that Black women face in the spotlight is mirrored in their private lives: an impassioned clip from Walker’s infamous Instagram live zeroes in on the singer forced to defend herself for simply stating that she preferred baths to showers.

The film’s score (an original composition by Jane that mixes Walker’s “Shame” with ethereal synths) offers a connective tissue for the clips that often double before they disappear, refracting and seeping in and out of each other’s screen time: an archive of Black femme performers pushing up against their limitations in professional spaces. “There are all these moments in “LetMEbeaWomanTM.mp4,” where I’m like: ‘I don’t think y’all heard her. Let’s play that back. Let’s slow that down,'” says Jane.

At one point, an edit of Jennifer Holliday belting “You’re Gonna Love Me” is mashed up with the lyrics “Look out baby a star is a slave,” then, “I don’t wanna be free.”

“By putting those words next to each other, that’s a moment where people understand,” says Jane, “that it’s a Faustian contract, the bind that you’re in: desiring hyper-visibility in a structure that started out of colonial violence.”

“As MHYSA, Jane turns their gaze inward, fleshing out an internal narrative for their musical alter ego. They draw from the stories of the women that they have spent their practice studying and vindicating. In a sort of artistic osmosis, they go from documenting Summer Walker to channelling her.”

Through their loving and meticulous archive, Jane arrives at a new framework for understanding American history: a safe space for Black women that challenges thinly veiled cultural moments of systemic racism, sexism, and media surveillance.

“I am not grappling with notions of identity and representation in my art. I’m grappling with safety and futurity. We are beyond asking if we should be in the room. We are in the room,” Jane declared in their 2015 “NOPE Manifesto.” The statement originated as a Facebook status after they attended Fred Moten’s lecture on “Blackness and Nonperformance” at MoMA, where, for the first time, they experienced a physical space that centred a community of Black luminaries such as Glenn Ligon, Coco Fusco, and Saidiya Hartman.

Inspired, they began an ongoing exploration of physical space underscored by a list of utopian demands: “We need more people, we need better environments, we need places to hide, we need utopian demands, we need a culture that loves us.” Their manifesto hurdles past the limiting binaries of identity art and outlines an expansive notion of Blackness, queerness, creativity, history, and of a sustainable future. “I reject the colonial gaze as the primary gaze. I am outside of it in the land of NOPE,” they wrote.

Jane lives out their utopian demands through their work. “In a state where Black people are expected to be hypervisible, the right to hide when you want is already a utopian demand. How do we refuse that surveillance? How do we play with that surveillance?” they ask. At their show at Kitchen, MHYSA’s rehearsal happened during gallery hours: visitors could eavesdrop, but they couldn’t come in.

Around the same time as they wrote NOPE, Jane created #CindyGate, a call for discussion and critique of the artist Cindy Sherman’s racist early self-portraits wearing blackface. “#Cindygate reflects larger systemic issues in art, spec. Whose body is expected in the gallery + whose body matters,” they Tweeted.

Their use of the Internet to subvert and disseminate ideas traces back to their childhood. They came to consciousness online as an only child in the suburbs of Prince George’s County, Maryland, surrounded by conservative Southern Baptist culture. From an early age, they were obsessed with the music of bonafide divas of the 90s: Brandy, Monica, Janet Jackson, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, Whitney Houston, Chaka Khan and Mariah Carey. (They began burning tapes of R&B they heard on the radio).

In middle school, they learned how to shoot and edit videos. “Talking through video really started for me there. It was the first language that I felt articulate in,” they reflect. Their interests in digital spaces and music came to fruition while they were in the MFA program at the University of Pennsylvania, where they found solace from the predominantly white spaces of academia through music as well as with a community of Black women and femme students and artists they met online.

“I remember there was a shift between my first and second year of grad school. where I was like, ‘I want to work in video, but I don’t know what I want to talk about, but I kept watching these music videos.'” They recall the music video for “Trippin,'” a song by R&B girl group Total and Missy Elliott that they watched on loop in 2016. “I thought, the women are in these pink frilly outfits, and they’re being really sexy, but they’re just with themselves,” says Jane. “That was really exciting to me.”

At the same time as they were honing in on their voice as a visual artist, MHYSA was born “in that middle space between doing a live experimental electronic set and performing for myself in the house.” Her first album came out in 2017, and she began touring soon after.

As MHYSA, Jane turns their gaze inward, fleshing out an internal narrative for their musical alter ego. They draw from the stories of the women that they have spent their practice studying and vindicating. In a sort of artistic osmosis, they go from chronicling artists like Summer Walker to channelling her.

As Jane has developed MHSYA’s image and sound, they have collaborated with photographers such as Naima Green, Elle Pérez, and Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. Today, collaboration still pulses through the project. They began working on their forthcoming EP with their life/work partner chukwumaa (together, the two make up the performance duo SCRAAATCH) and fellow musicians Abdu Ali and Bapari in the summer of 2020 after they arrived in Brooklyn from Philadelphia. Around the same time, they began taking vocal lessons with Nicholas Ryan Gant.

While MHYSA is an entity unto herself, her identity is connected to Jane, as well as the Black divas who came before her. “I’m thinking about my own interiority in some ways, how my interior needs relate to performance,” Jane offers. “I root it in her because I’m thinking about myself a bit, like what needs to be put back into me? But then I am also thinking about how divas have performed divadom over the years,” they say.

Jane asks themself, “What does the empty vessel need to be filled with?” as they prepare for MHSYA’s upcoming performances, including their live show at Pioneer Works at the end of the month.

Written by Meka Boyle

E. Jane: Drenched in Light

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, until 01 October 2023

MHYSA: Release Control Performance

Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, 8pm, 29 September

“Release Control”is out 06 October 2023

FIND OUT MORE