Conceived as “a tapestry of shared histories and stories”, Gathering’s newest show translates our state of interconnectedness onto images that speak of us all

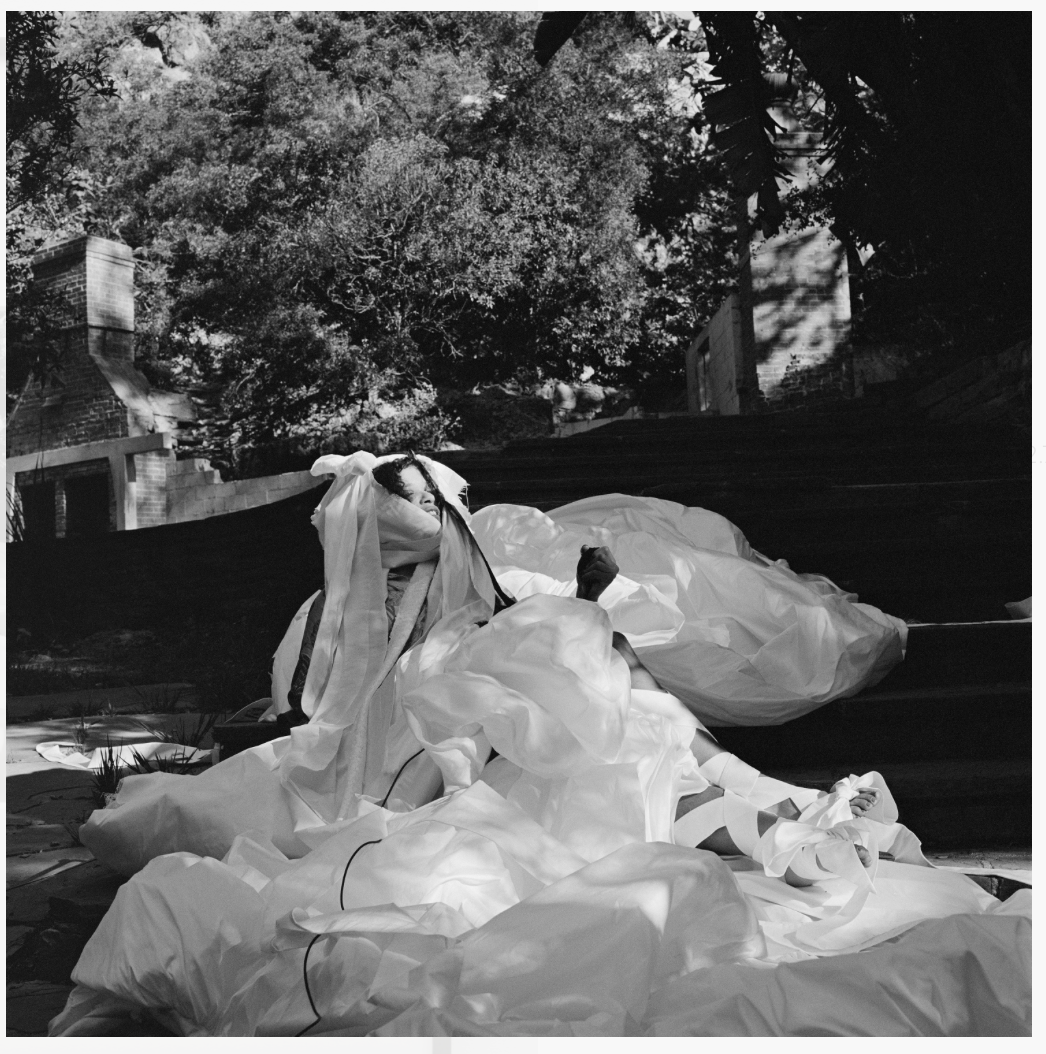

There is something effortlessly organic and coherent about the selection of artworks brought together in Pictures of Us, the newly inaugurated group exhibition currently on view at London’s Gathering, Soho. It seems as if, rather than standing out for their own signature aesthetic, the photographs and film installations inhabiting both floors of the gallery moulded into one long, uninterrupted sequence of human stories, at once expanding and complementing each other. As I stare at them starting from the right-hand side, my gaze is naturally transported from one print to the next and the following one in an almost hypnotic, linear flow. Heralding this immersive experience is artist, filmmaker, writer and activist Tourmaline’s Silver Cloud I: a black-and-white shot whose sunkissed, vaporous atmosphere was enough to capture my eye for entire minutes and stop time altogether. Next to it hangs a monochromatic visual quartet by British-Congolese multidisciplinary creative Bernice Mulenga, whose grainy portraits of friends — framed in electric blue — render the overlooked magic of everyday togetherness.

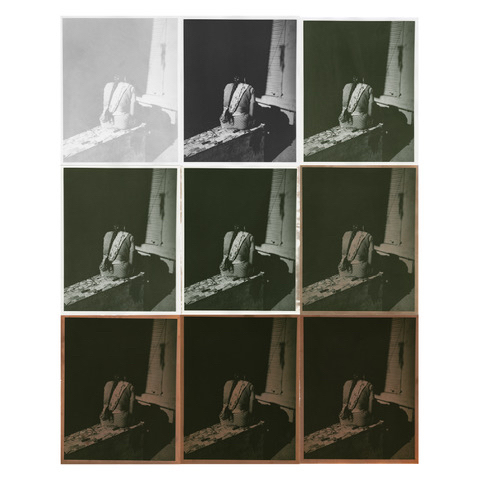

Sitting on white plinths placed in the centre of Gathering’s main room are Tweeky (2022) and Gotcha (2022), two woodblock puzzles by London-born artist Lotte Andersen. Plastered with a photograph taken from her family album on both surfaces, each one of the pieces belonging to these fragmented compositions can be flipped, moved and positioned as visitors please, thus encouraging live interaction with the artworks on display. A readaptation of an image part of her aunts’ personal archive, the first one of Andersen’s wood-cut puzzles, portrays the wide-eyed, heartwarming face of a baby called Nancy. Gotcha, on the other hand, appears to show that of a teen, though the cartoonish silhouettes into which the original shot was fractured keep the artist’s work open to the most disparate interpretations. Moving away towards the opposite side of the space, the public is met by Vivek Vadoliya and Jess T. Dugan’s contributions to the show: the former sharing six hand-printed replicas of the same haunting photograph of an Indian woman dressed in traditional clothing, her dark hair gathered in a braid falling down her back; the latter, three softly-lit images grappling with domesticity, intimacy and the body.

If there is anything binding each of the works on view on Gathering’s main floor, that must be how the sensorial experience of light is embedded in them. Shifting from dawn to dusk with numerous images captured at sunset, this collection of shots acts as a sundial, keeping time on the human experience, the rituals associated with it and the moments through which it unfolds. Even stronger, though, is the unexpected sense of familiarity that pervades these vignettes of life, making it instinctual for viewers to feel somehow connected to those presented in them. “With its title, Pictures of Us refers to the fact that these narratives should touch all of us, whether we identify with a particular community or not,” Lewis Dalton Gilbert, curator of the exhibition, tells Elephant. “In this regard, my aspiration is for the showcase to act as a catalyst and inspire a collective sense of humanity — something we all need right now.”

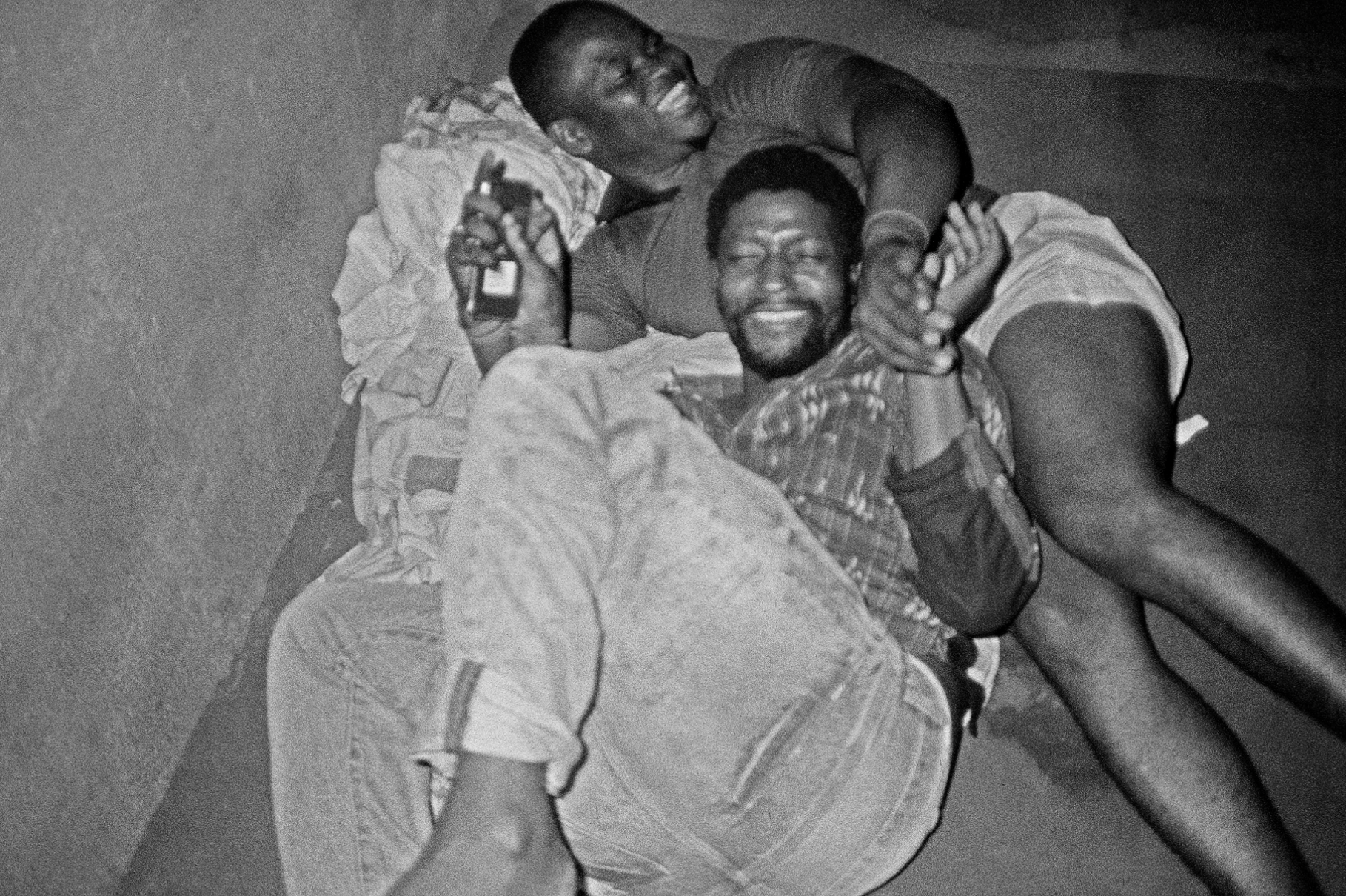

It doesn’t take much to give in to the tenderness of Genesis Báez’s hazy, poetic documentation of family: brought to the audience in the form of three Hahnemuhle photographic prints, her work visualises the inborn complicity and secret language of the maternal bond. Through a play of blurred silhouettes, the Brooklyn-based artist not only captures her mother but she also leaves a margin for everyone else to project themselves into her delicate compositions. The same can be said of the selection of photographs taken from Sabelo Mlangeni’s 2020 series The Royal House of Allure: an uplifting, joyful exploration of the relationships surfacing within the walls of a house in Lagos that was conceived as a refuge for queer people in need of boarding. Developed over the course of six weeks, this grainy diary looks at the quotidian of its guests, detailing the candid minutiae of their communal living. Also featured in Pictures of Us are some of Mlangeni’s photographs of the George Gogh Men’s Hostel and its inhabitants, many of whom have dealt with poverty and exclusion. By redirecting his lens away from the challenging situation of his sitters to zoom in on their personal dimension, in both of these instances, the photographer reclaims his subjects’ right “to define themselves outside of hegemonic culture”.

Still, as Gilbert puts it, rather than simply relying on photography and moving image to amplify the reality of a given community, “the exhibition seeks to underscore the interconnectedness of individuals with the broader human experience, inviting viewers to reflect on their place within its intricate tapestry of shared histories and stories”. It is a mission that echoes through Alberta Whittle’s film The Axe Forgets, one of the audiovisual pieces showcased in the intimate theatre installed for the occasion on Gathering’s lower floor. Calling, like a great part of her oeuvre, for a return to nature and its rawest elements, the artwork fuses dreamlike sequences of bodies and water in motion with material sourced from the Hackney Archives and clips of interviews with her family members and Hackney’s Windrush residents. Rejecting the understanding of historical archives as fixed in stone and static, the Barbadian-Scottish multidisciplinary talent borrows from the social ferment that characterised Commonwealth migrants’ life in post-war UK to restitute a picture that honours their zeal, legacy and contribution to British society.

Part of the film-based offering of Pictures of Us, which comprises more works by Andersen, Dugan and Báez, is Matthew Arthur William’s Soon Come (2022). A multisensory installation translating the reach of his diasporic heritage into a story that dissipates the boundaries between truth and imagination, landscape and the body, analogue and digitised footage, the piece immerses the audience in a liminal mindscape that superimposes views of the Jamaican parish of Clarendon — where his mother was born — with those of Stoke-on-Trent — where she grew up. Speaking on the relevance of the group exhibition and the reflections sparked by it, Gilbert argues that “while each individual is a unique thread in the grand design [of humanity], Pictures of Us illuminates the profound truth; or that our uniqueness can, in itself, act as a unifying commonality”. Praising the way in which the participating artists turn to their medium as a means of confronting challenging aspects of their existence, the curator explains that, at a time when more and more people are being silenced for expressing their views on sensitive issues, “art should provide a sanctuary for creators, allowing them the freedom to craft their work unencumbered by the constraints of censorship”.

An enthralling, complex portrayal of the human spectrum, rather than aiming to convince viewers to overcome the differences that set us apart, Pictures of Us serves as a jubilant celebration of our shared human fabric by focusing attention on what brings us closer together. “Many divisions among us are either enforced or subtly encouraged by a vocal minority,” Gilbert concludes. “In acknowledging this, we empower ourselves to dismantle the barriers that hinder our collective growth and harmony and lay the foundations for a common future.”

Words by Gilda Bruno

Pictures of Us is open at Gathering, London, through 13 January

find out more