For her first institutional UK exhibition, Green in the Grooves, Tamara Henderson takes us by the hand and walks us through her chaotically poetic world. Leading us, with hope, to an intimate relationship with the earth and the possibilities of a shared future.

The exhibition is a landscape of dark and light spaces, dotted with glass candle holders that peel at the top like globulous bananas – the flickering flames enlivening each space. The first room holds a museum-like quality. Dimmed lighting and spotlit paintings of frogs and worms meeting together, their mouths in a half smile, with lipsticky pinkish lips. The frames, instead of the gold baroque style typical of a museum, are deep blues and vibrant yellows, with large wave-like pieces strutting out into the space. The frames are coated in a layer of thick material, which has been fingered and poked at, giving them the look of soil that has been pushed around and compacted after planting.

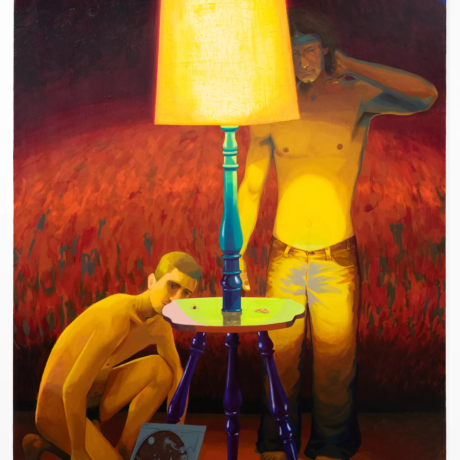

In this room, the manifestations of the four main characters in Henderson’s compost-scape – The Gardener, The Director, Sound, and Light – spin slightly too fast to be comfortable and slightly too slow to be characterful. It is this in-between of fantasy, absurdity, and the earthly realm that all works in this show come to life. The spinning outfits of these manifestations are sculptural portraits, each made with intense detail: The Gardeners’ jacket is stuffed full of seed packets, nasturtiums, sage and sweet basil. On another sculpture, there is a cyanotype-printed jacket and skirt, beautifully tailored with a toned patchwork of navy, orange and yellow. Grids, peace signs and puzzle pieces are exposed on the surface, glowing in white, just one example of the microscopic qualities in all the works in the show. The zooming-in on the complex detail of each piece is much like looking at a leaf under a microscope and seeing the cells and veins that constitute its makeup.

Behind a curved brick wall, a film plays, delving into the archaeology of each work and their earthly identities. In one shot, two ball magnets connect metal filings; pulled slightly apart, the filings are stretched through space with a glimmer of light dancing across the 16mm film. In another, more spinning structures form into cone-like shapes, this time in front of an open garage, rotating to the blaring of disco music. With each shot, another layer is removed, like a dancer peeling off a jacket, then a t-shirt, until all that’s left is their spinning frames, dancing with abandon.

From here, we move through a jarringly bright installation, timber-framed arches peppered with speakers amplifying the mulch digestion of the composting bin, which throbs in the centre, and onto a room which is home to a greenhouse charged with emblems. The walls are decorated with small plastic objects, the unnatural colours of this man-made material pop from the glass walls, puzzle pieces and letters from children’s games. Trinkets and necklaces are motorized, rising and falling with a watery rhythm. The floor of the greenhouse is hose pipe, cut and drilled into place in spaces that resemble the previous 3D frames. It becomes clear that the trinkets are the same objects that littered the costumes in the previous room as if those marks had actually been made in the greenhouse, etched and sunbleached onto the clothes as though the character had overworked in the space, becoming too immersed in the task at hand.

There is something of the above and below in this exhibition, a spirituality mined through the earth. The energy in this is consuming, a tactile relationship to the earth, which is both charming and effusive. There is also a pull towards the domestic, the greenhouse and its suburban equivalence, the garage, and the frogs communing within the safety of frames. This seems to not be nature with a wild and ferocious attitude but Mother Nature, with her flourishing moments of nurture. The works are networked, a community with its own microclimate. There’s a demonstration of reliance on each other in a holistic sense, a deep caring understanding and crucially, an alive communion with the earth that surrounds us, being the only chance we have for us all to protect a possible future.

Words by Lisette May Monroe