Before lockdown, the first thing that I would do when I got home from work was open the fridge. Now that I find myself rarely out of the house, it is an impulse that has nevertheless stayed with me; an unthinking gesture towards normality that punctuates the day. The desire to eat when bored is a common one, but a restless appetite represents more than just greedy distraction. From idle snacking to elaborate meal preparation, the food that we eat evokes heritage, knowledge, travel and the chasing of desire.

The fridge is a cultural and class signifier, revealing our habits and tastes as individuals—from pickles to dairy products. While rooted in the deeply personal domain of the domestic sphere, the fridge is just as representative of its era as it is of singular preferences for, say, oat substitutes over cow’s milk. Just as recipe books from the 1970s have the uncanny ability to conjure vivid pictures of a cheese-and-pineapple fuelled cocktail hour, so does the refrigerator offer unexpected insight into its age.

For William Eggleston, the pioneering colour photographer, seemingly everyday subjects can communicate volumes about their time and place. He has spent more than five decades turning his lens upon unlikely scenes and nondescript objects, often situated in the American South and Southwest. Food and its various trappings recur in his images across the decades, from a lonely assortment of ketchup and mustard bottles in a roadside diner to a glistening roast chicken on a freshly laid red-and-white checked tablecloth.

Eggleston’s photograph of his own ice-encrusted freezer, titled Memphis (after its location in his Tennessee hometown), gives an intimate slice of the underside of 1970s America. Processed foods, beef pies, ice cream and “tasty taters” pile together in a brash, artificially-lit still life. It is a haphazard array of pastel packaging. There is an immediacy to Eggleston’s images that elevates even the most mundane of subjects. “I never think about it beforehand,” he explained of his process in an interview with the New York Times in 2016. “When I get there, something happens and in a split second the picture emerges.”

- Courtesy Chef & My Fridge

“From idle snacking to elaborate meal preparation, the food that we eat evokes heritage, knowledge, travel and the chasing of desire”

Not only the food that we eat, but the brands that we choose can give away more than we would like to admit. Some, like Campbell’s Soup, become so ubiquitous that they travel far beyond the supermarket shelves. Andy Warhol was rumoured to sustain himself almost solely on the brand’s tinned soup, which led him to famously immortalise them in his 1962 eponymous work. “I should have just done the Campbell’s Soups and kept on doing them … because everybody only does one painting anyway,” he later admitted.

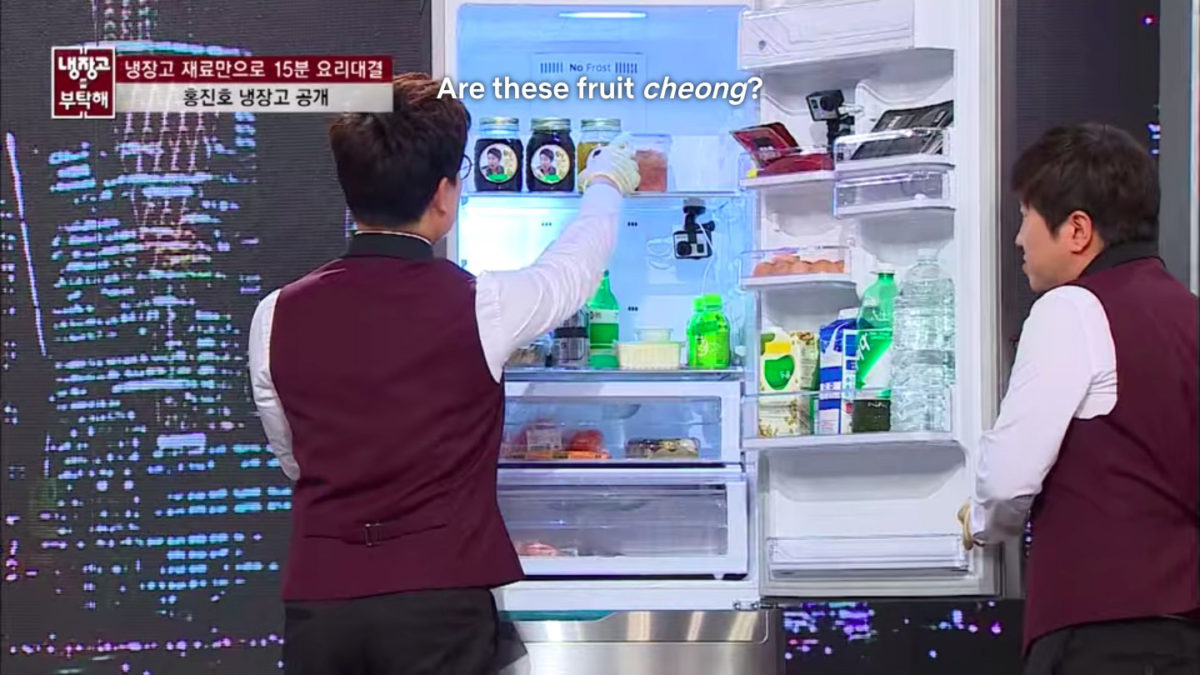

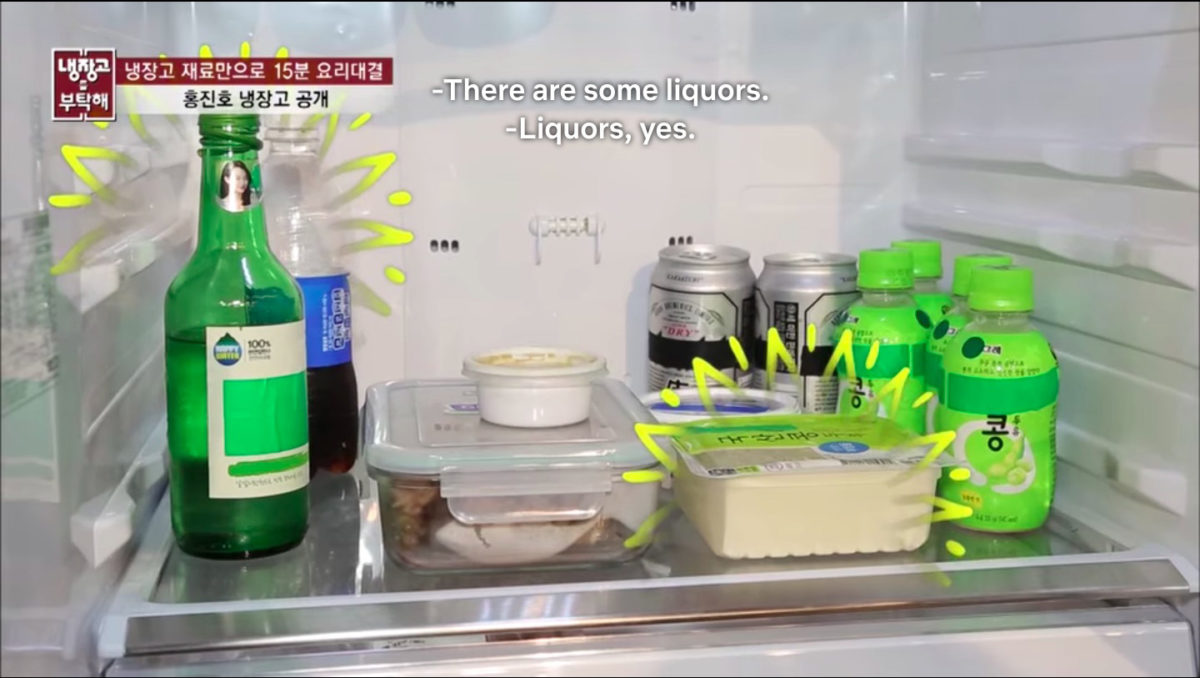

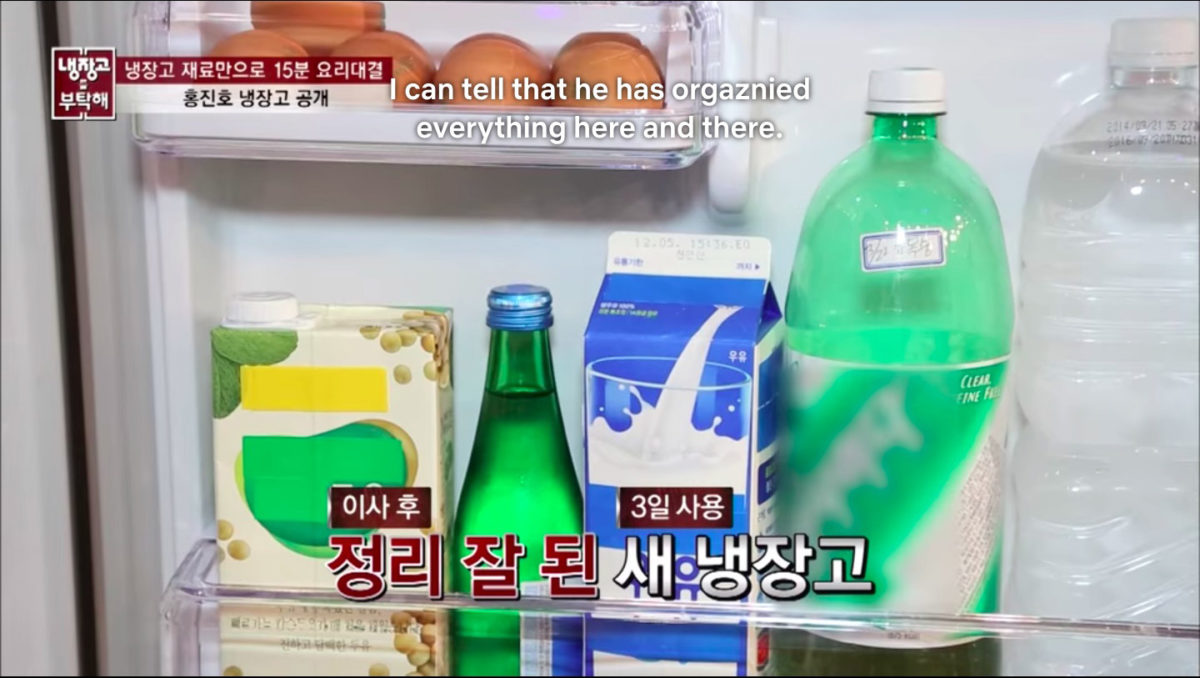

There is mystery and intrigue surrounding kitchen cupboards and the fridge—a fascination well suited to the public’s interest in the private lives of celebrities. South Korean Netflix cookery show Chef & My Fridge takes this intrigue as its starting point, inviting two celebrity guests per episode to expose the contents of their fridge to an array of professional chefs. It does what it says on the tin, and is billed as: “The project that turns your leftovers into an amazing dish! The best chefs in Korea will take care of your fridge!”

Of course, part of the fun is the exterior and general design of the fridge as much as its contents. How many magnets adorn its front, and how neatly are the condiments stacked inside? Could it all do with a good clean? Chef & My Fridge delivers the goods by quite literally winching each guest’s refrigerator into the studio. The show’s merciless presenters then proceed to pull on gloves, pull open the fridge door and explore them inside out, with a fair amount of shit-talking and mockery along the way. “Did your mother really make this?” one asks, “It tastes awful!” Animations flash frequently across the screen, highlighting flushed cheeks of embarrassment or a particularly ruthless stare. Taken together, it’s an assault on the senses.

Following a thorough examination of each fridge, the chef competitors must each select items with which to concoct a dish in just fifteen minutes. Curious hybrids emerge, from instant ramen seasoning used to season a sauce, to soy milk and crushed biscuits transformed into an elevated dessert. “It tastes like food from a convenience store,” one guest exclaims. Another is more generous, declaring with admiration: “How can dishes like these be made from my refrigerator?”

“The fridge is at once a great leveller and a source of anxiety and alienation. After all, no two fridges are the same”

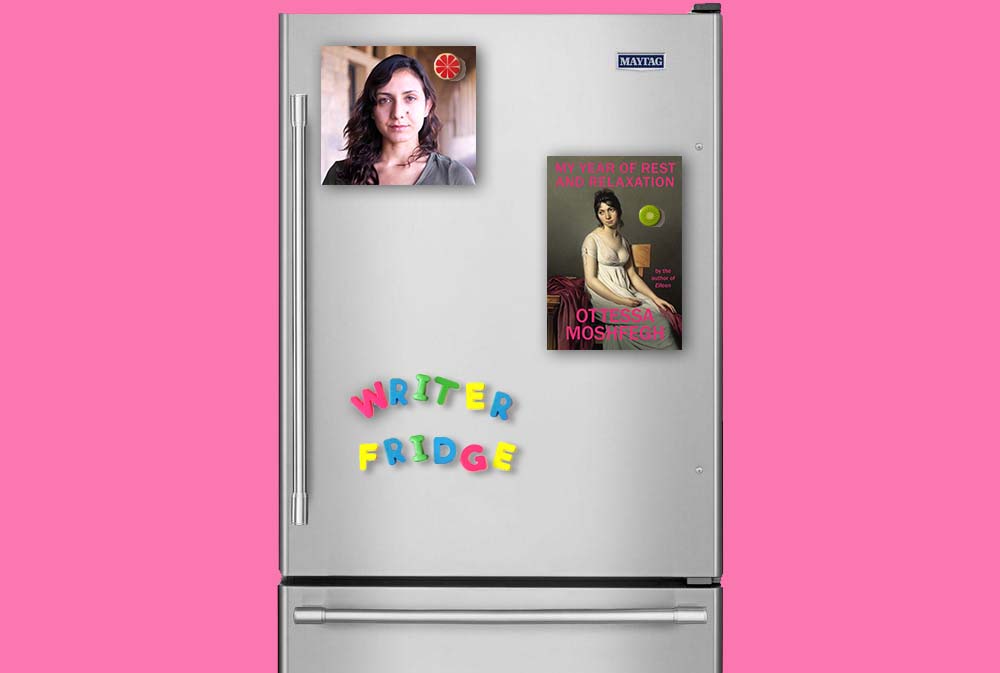

Our fascination with the fridge and its contents is not limited to celebrities within the pop cultural realm. The Paris Review runs a regular column titled, simply, “Writer’s Fridges”. It seems that literary types are just as intrigued by the fridges of their favourite authors as any of us. The series wryly promises to “bring you snapshots of the abyss that writers stare into most frequently: their refrigerators.”

And who better to explore the abyss than the darkly comic chronicler of our alienated times Ottessa Moshfegh, author of My Year of Rest and Relaxation. “Do you see that half-eaten can of tuna on the top shelf? That was a mistake. Most of the food in my fridge is inedible”, she dryly recounts. Other featured writers include Olivia Laing (pomegranate molasses and aubergine pickle) and Jia Tolentino (strawberries and hot sauce). Every uneaten bag of salad leaves and each extravagant bottle of champagne allows us to feel that we know the owner of the fridge a little better, and that we could begin to understand them. Like those who obsess over the daily rituals of famous creative people, it might even bring us a little closer to them.

The fridge is at once a great leveller and a source of anxiety and alienation. After all, no two are the same. The kitchen is often said to be the heart of every home, where domestic dramas play out amidst the pots and pans. Adorned with personal snapshots, postcards and novelty magnets, the fridge offers a freeze-frame of these intimate lives—suspended in something as innocuous as an array of condiments. Like Eggleston’s instinctive eye for the most unremarkable of subjects, the refrigerator has the surprising potential for truth.

Top image: William Eggleston, Memphis; negative about 1971; print 1980 © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Caldecot Chubb