There was no greater documenter of the second half of the twentieth century than Andy Warhol. In the 1960s, with his Bolex and Auricon movie cameras, he documented the goings-on at his legendary studio, the Factory, where he held “open house”. In the seventies he went forth every night into the New York social world, armed with his Polaroid camera and tape recorder—which he referred to as his wife—and snapped away in search of portrait commissions. And in the eighties, via his TV shows, videos, photography, audio recordings and Time Capsules, he would document—well, everything. On top of that there was all the art, of course.

There was no greater documenter of the second half of the twentieth century than Andy Warhol. In the 1960s, with his Bolex and Auricon movie cameras, he documented the goings-on at his legendary studio, the Factory, where he held “open house”. In the seventies he went forth every night into the New York social world, armed with his Polaroid camera and tape recorder—which he referred to as his wife—and snapped away in search of portrait commissions. And in the eighties, via his TV shows, videos, photography, audio recordings and Time Capsules, he would document—well, everything. On top of that there was all the art, of course.

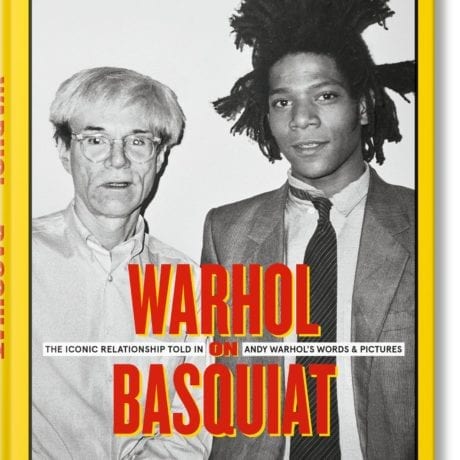

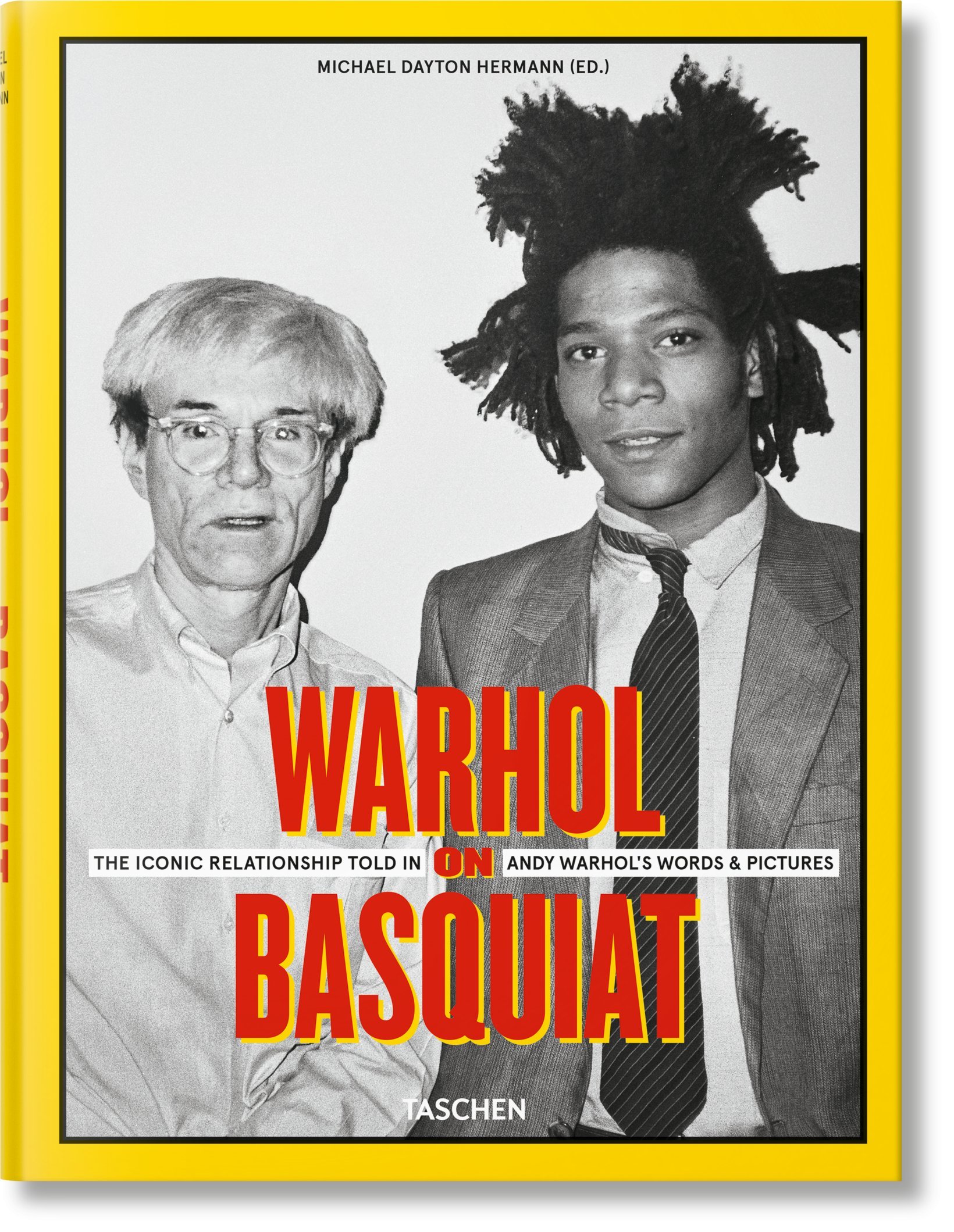

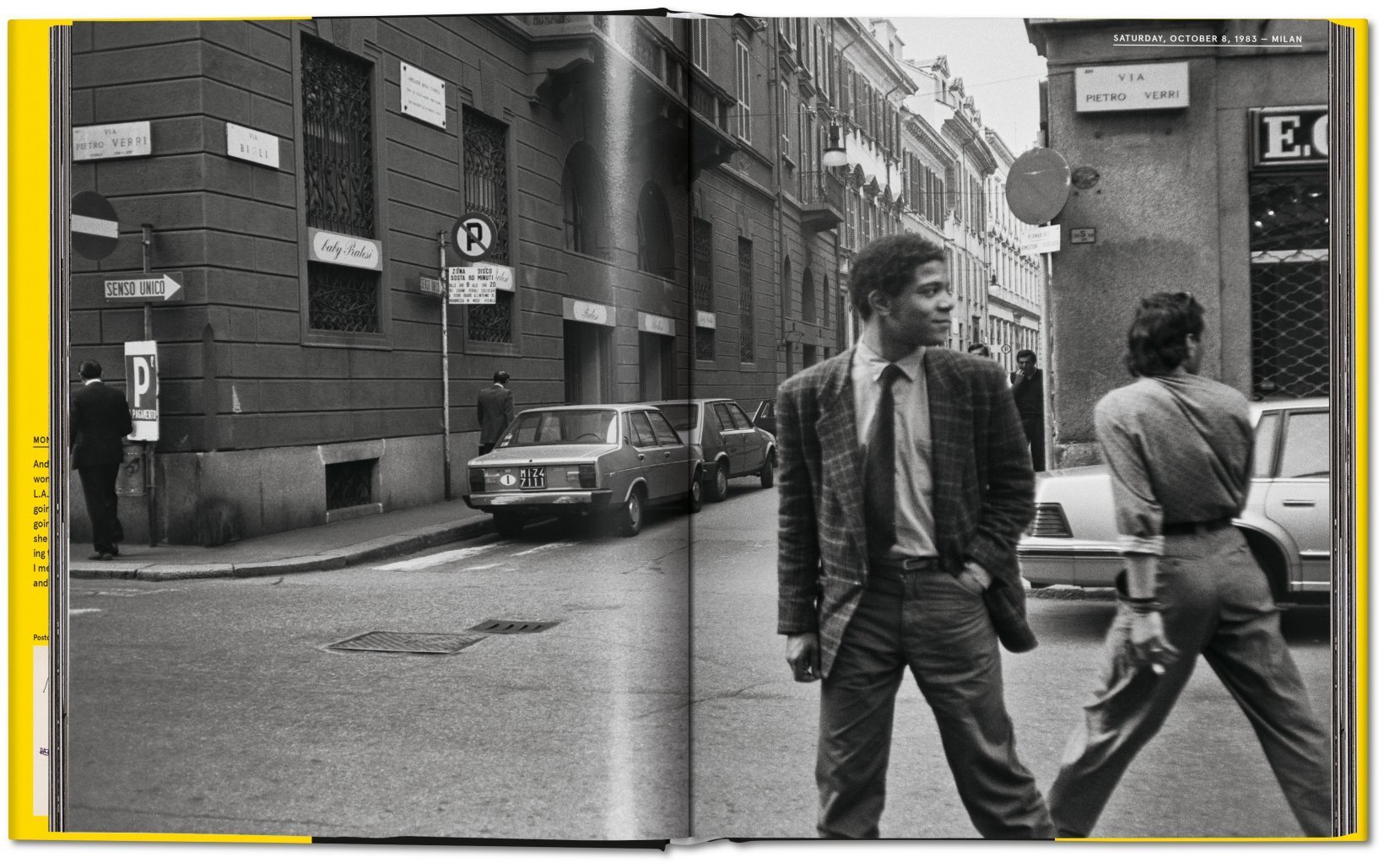

So if you want to know about Andy’s relationship with Jean-Michel Basquiat in the early eighties, the place to begin is the Warhol archives. Which is what Michael Dayton Hermann did to create this wonderfully rich visual and verbal resource, which draws on Warhol’s photographs and his words from his published Diaries, to create a complex portrait of the two men’s relationship.

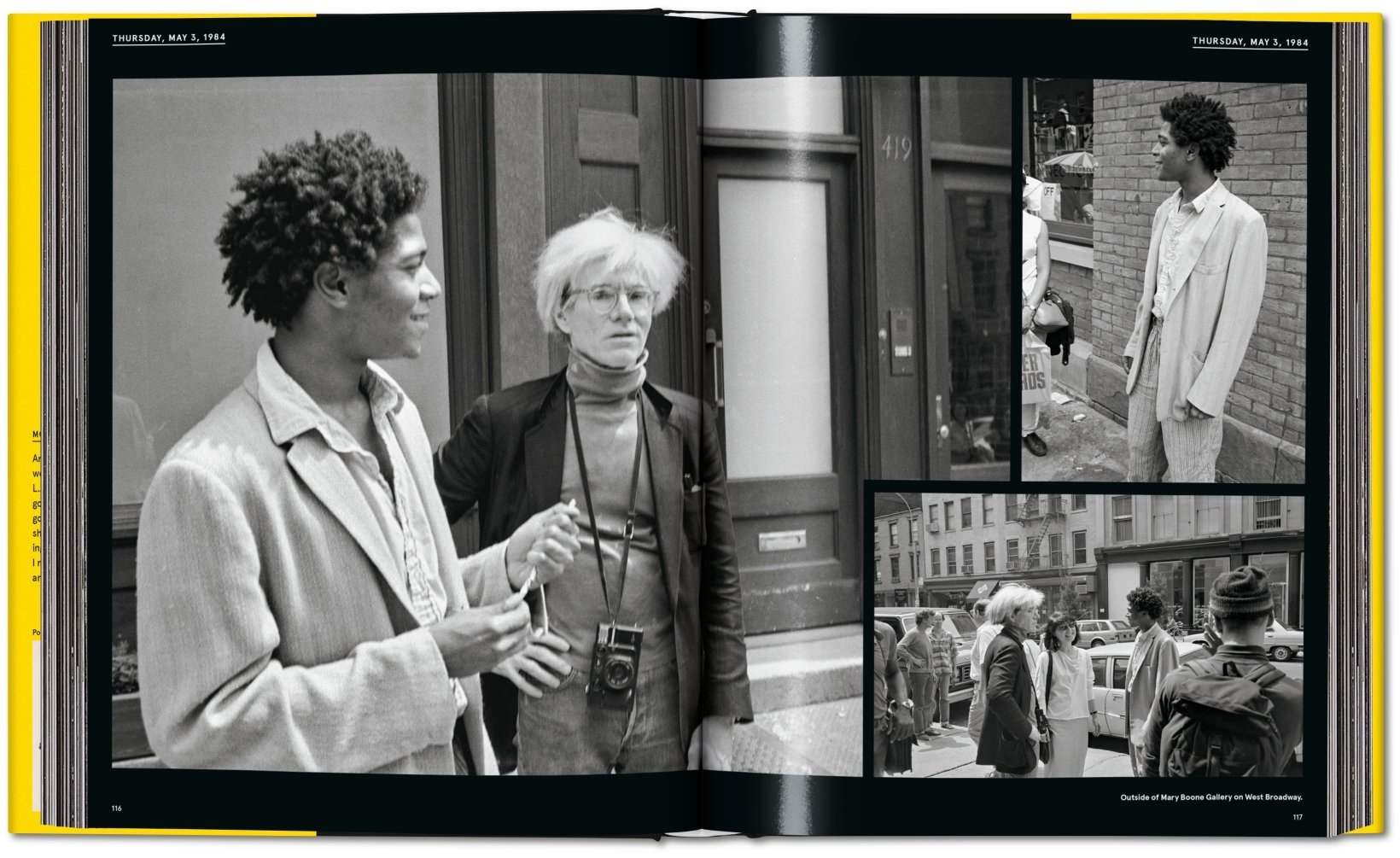

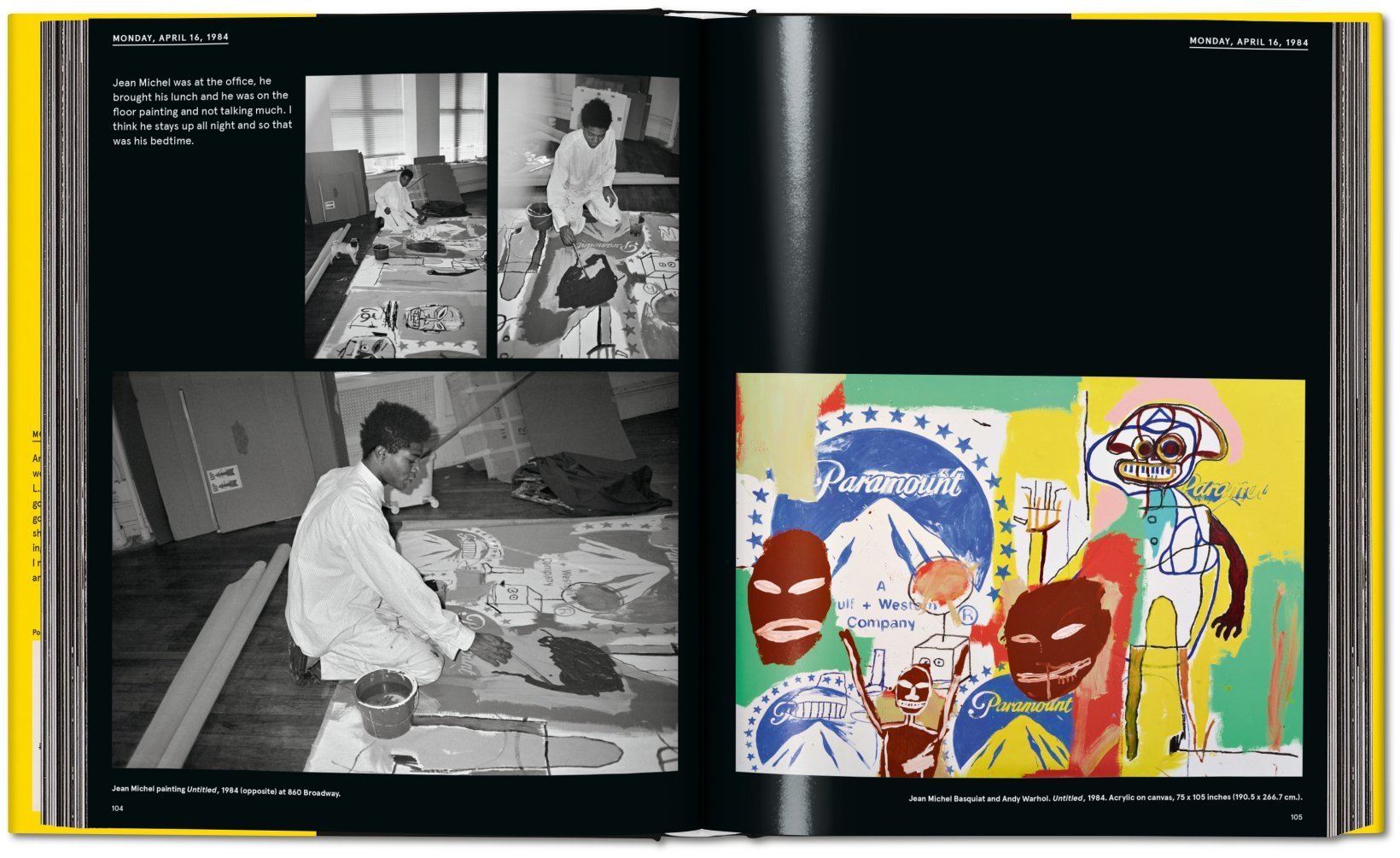

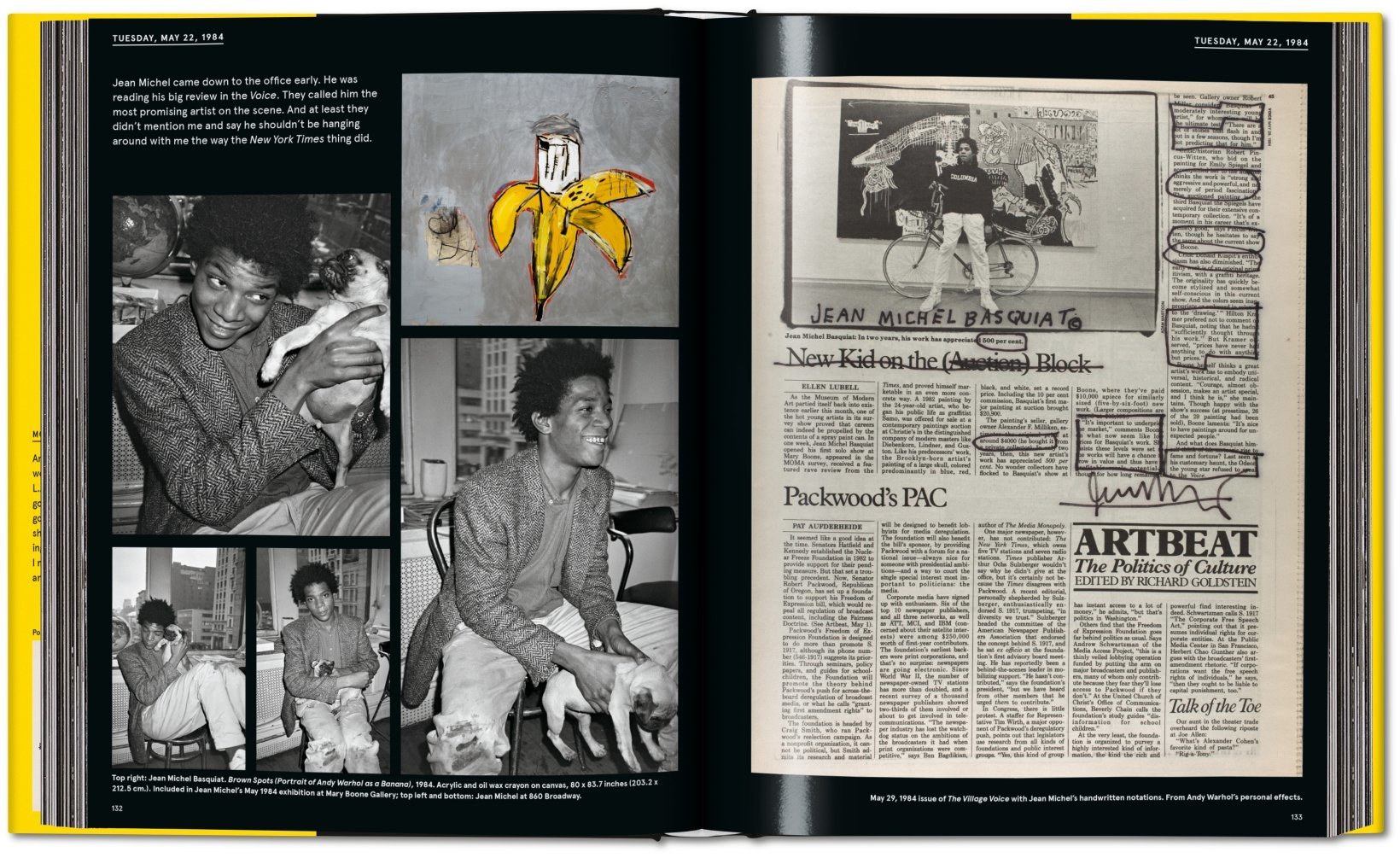

In artistic terms, Basquiat saved Warhol’s life—or at least revived his ailing creativity. He convinced Warhol to return to painting by hand, and Warhol certainly acknowledged a positive artistic influence from the younger artist. “Jean Michel got me into painting differently, so that’s a good thing,” he noted in his Diaries. They made playful portraits of one another: Basquiat offered a homage to Warhol in the form of a painting of a peeled banana on a silver ground which formed the centrepiece of his first one-man show at the Mary Boone Gallery in May 1984, while Warhol did one of Basquiat in his briefs as Michelangelo’s David. They even exchanged hair.

We asked the author about the experience of putting the book together.

How would you sum up the relationship between Warhol and Basquiat?

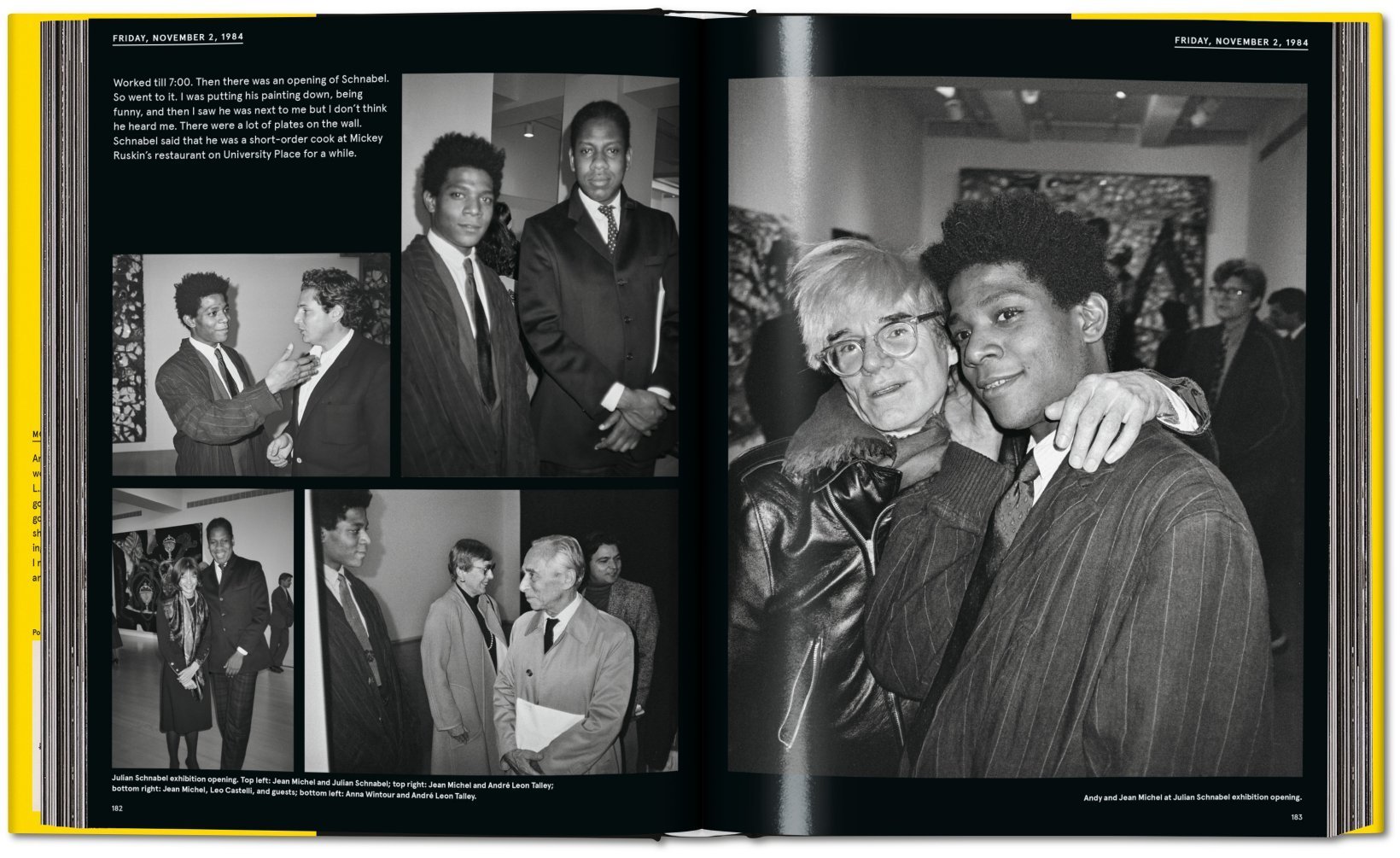

Warhol and Basquiat’s unique relationship defies any easy characterization other than to say it was complex. As I put the book together I was continually surprised by the emotional depth of what was clearly a caring relationship among two nearly mythical figures. Moreover, it was fascinating to see how much they genuinely enjoyed one another’s company—from dinner parties to hotel rooms to the gym and, of course, the studio.

The book contains over 400 photographic images. How do you approach research when you’re working with someone like Warhol, who was such a relentless documentarist of his own (and everyone else’s) existence?

Over the course of many years working at The Andy Warhol Foundation, I’ve become quite familiar with the vast photographic archive. This foundational knowledge proved to be essential when navigating 130,000 photographic negatives to be interwoven with diary entries, artworks and archival material.

The photographs, which appear to detail every moment of the artists’ relationship, have been compared to a social media feed. Is that a reasonable analogy?

Warhol on Basquiat uses the contemporary diaristic language that is so familiar in our social media-obsessed moment. However, it is striking in its refreshingly honest depictions, clearly not staged to market a lifestyle that will result in more likes and followers.

The source for the text is Warhol’s diaries. Shortly after Warhol’s death, when they had just been published, Lou Reed sang: “Your diaries are not a worthy epitaph.” Was he right? They seem a fairly rich resource in the case of Warhol on Basquiat.

The Andy Warhol Diaries are full of astute observations and unexpected candour, sprinkled with catty gossip. Yet its real strength is that it generously humanizes Warhol. It allows the reader to get beyond his caged veneer and into his head. Warhol left behind a vast and complicated legacy so it should go without saying that no single contribution could be a worthy epitaph. However, Warhol himself left us with something interesting to ponder about his own absence when he said, “When I die I don’t want to leave any leftovers. I’d like to disappear. People wouldn’t say he died today, they’d say he disappeared. But I do like the idea of people turning into dust or sand, and it would be very glamorous to be reincarnated as a big ring on Elizabeth Taylor’s finger.”

You work for the Warhol Foundation and at the same time maintain your own art practice. How has the former influenced the latter (and vice versa)?

When I came to work at the foundation as a young artist, I took for granted much of what Warhol did. Over time, what resonated with me personally was his bold embrace and fearless celebration of nonconformity. In this moment when many artists are celebrated for creating unoriginal work that is often not much more than a luxury product, it is helpful to be reminded of Warhol’s early embrace of the avant-garde.