Ian Wolter is openly political in his practice. Most recently, he has been working on a sculpture called The Children of Calais, which will be shown to the public from this Friday at Dorset House Garden, off Church Street, in Saffron Walden in the UK. The piece is being unveiled by Lord Dubs, a Labour party peer and former child refugee, in a fitting nod to the sculpture’s roots. It depicts six children in contemporary clothing, one holding a life raft, in a pose reminiscent of Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais. Like the original, this work comments on an “inhumane” act by the country’s leaders, as the government has about-turned on a previous promise to take in 3,000 unaccompanied children. “I wanted to make a very vivid, very solid response,” the artist tells me.

Can you tell me a little about The Children of Calais project?

This project grew directly out of an argument with an MP. His contention was that child migrants and refugees couldn’t be allowed to enter the UK, even if they had the legal right to come here, because that would encourage others to follow. That struck me as utterly inhumane. I think this view is sustained by keeping refugees in a rather theoretical realm, keeping them as “other”, a view perpetuated by the right-wing press. In Calais, when face to face with these young people, who could not want to help them?

“As with Rodin’s sculpture, the figures don’t look at one another; they are lost in their own despair”

I wanted to make a very vivid, very solid response. The story behind Rodin’s Burghers of Calais seems to present a similar narrative of a sacrifice demanded with the possibility of a positive outcome. Rodin’s piece commemorates a moment during the Hundred Years’ War when Calais was besieged by the English. King Edward offered to protect the city if six of its burghers would surrender themselves to be hanged. The burghers’ lives were eventually spared by the intervention of the queen at that time.

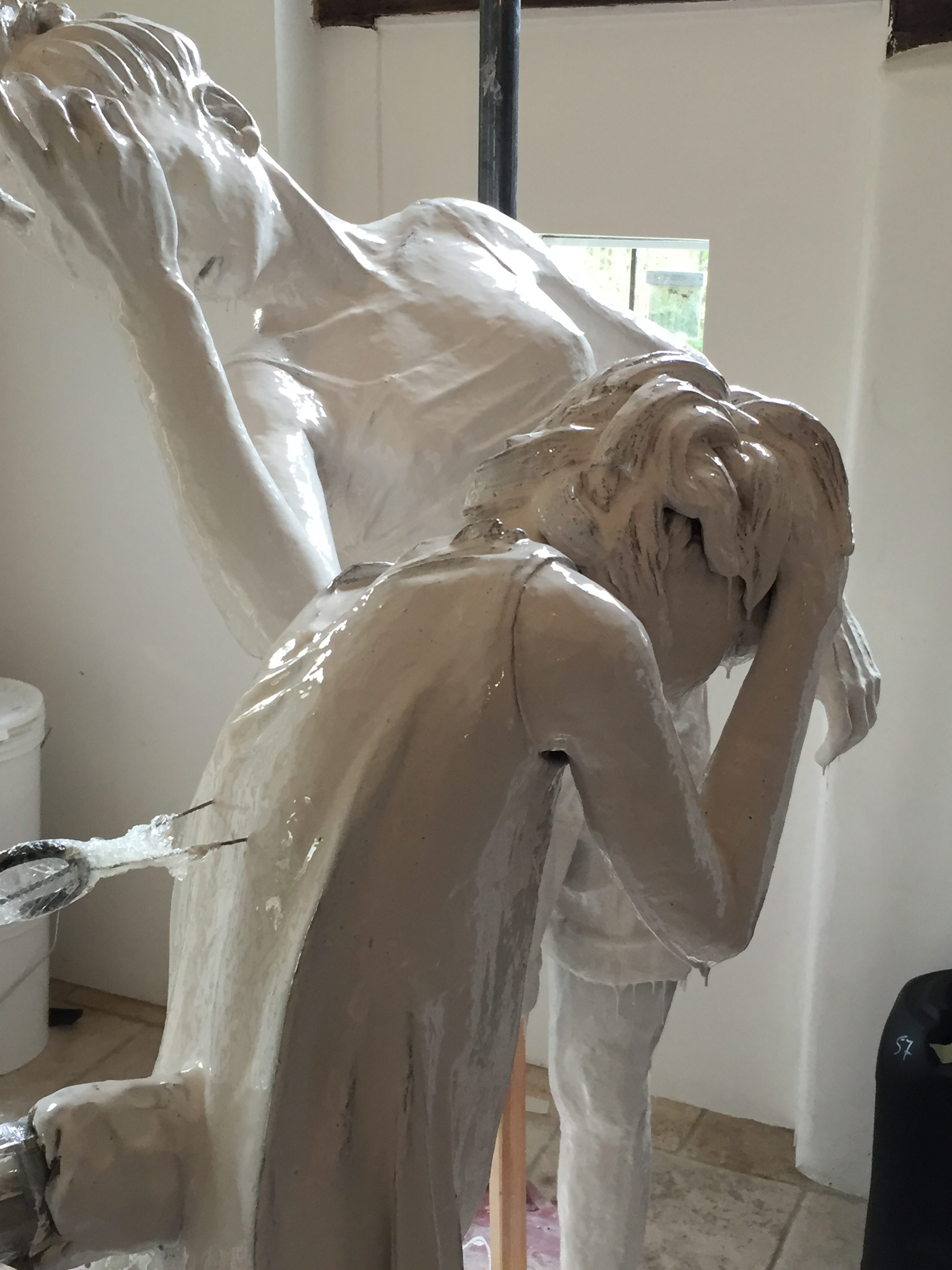

My piece, The Children of Calais, portrays six contemporary British children in the same poses as Rodin’s burghers. Instead of holding the key to the city of Calais, as in the original, one holds a life-jacket. As with Rodin’s sculpture, the figures don’t look at one another; they are lost in their own despair. The parallel in the stories of human suffering, forced migration and eventual grace is very powerful.

You worked from life on the project. How did you select the children for the sculpture (was there anything in particular you were looking for when you began?), and what was your process for working with them like, where the subject itself is very harrowing?

The first model was my daughter so I had no choice in that: she insisted! Thereafter I was interested in how tall they were and I wanted a balance of gender and ethnicity. The effect that I wanted to create was just a collection of British kids. The other five models were all children of my friends and it became a fascinating process. All of them were very highly motivated to be a part of the project because they felt very strongly about the politics involved. They were aged between nine and seventeen and most were well informed about the issue. Several didn’t want to be paid because they just wanted to lend their support to the project (I had to insist).

The other really interesting thing was that I spent between twelve and fifteen hours with each child and you don’t normally get to know your friends’ kids that well. I was really struck by what engaged, interested young people they all are.

I also went to Calais with Art Refuge UK and Secours Catholique to better understand the situation, which is truly shocking and is no longer being reported.

You have formed the sculpture in resin and made it look like bronze. Can you tell me a little about your play with materials and with the traditional aesthetics of public sculptures and memorials? Obviously your previous work caused quite the stir, with James Delingpole and Viscount Monckton threatening legal action…

The piece I made a few years ago, called Memorial, addressed climate change and the idea that those who had deliberately delayed efforts to tackle global warming should not be allowed to have their actions forgotten. I was inspired by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC but made this piece as a slow “waterfall” of oil trickling over the names of known climate change deniers apparently carved into a marble memorial. I think what aggrieved Delingpole and Monckton so much was the air of permanence implicit in the form of a memorial—that it would be a lasting record of their denial.

“Not all of my work is so direct in its message, but it seems to me that we live in a time when it’s important that we stand up and say what we believe”

I want The Children of Calais to work in a similar way, to be a reminder that the decisions we make now will be judged in the future. With a different material it could seem more contemporary, transient, ethereal or whatever; bronze feels permanent. This way it should be read as a permanent indictment, a record of inhuman decisions and policies, or equally it could be seen as a memorial to the young victims of the present crisis.

What response do you hope to trigger with a work like this?

It would be great if The Children of Calais prompted further debate about a more humanitarian response to the present crisis. Will it change anyone’s mind? I don’t suppose I’ll ever know. But I would like to think it could encourage people to have confidence in their own kinder, better nature, and speak out.

Many artists I speak with, even when their work touches on political subject matter, will say they aren’t outwardly political. You have made a very clear statement here in having your work unveiled by a Labour peer and former child refugee. What more do you think art can do to break through into political life?

Most art doesn’t attempt to impart a direct message. Political art does; it’s a very strange subset of art. When it works well, this is conveyed in the medium and the form of the piece, not just as a cartoon or slogan. It embodies the message in a new and hopefully thought-provoking way. Many artists shy away from being too literal, or don’t want their art to be dominated by a political stance or message, which I understand. Not all of my work is so direct in its message, but it seems to me that we live in a time when it’s important that we stand up and say what we believe.

All images The Children of Calais, final work and process photography. Courtesy the artist