I always used to be the most cynical person in the room. At school, I was known as the Ice Queen. Now I’m the person who weeps at episodes of Queer Eye and hugs strangers at weddings. Have I gone soft? Is this what people mean when they say that having a baby changes you?

In half a year as a mum, I’ve had plenty of unexpected experiences. Some of them have been alarming; such as post-partum hair loss, which for me kicked in around four months and is still going. The few hairs that have remained attached to my head are tugged constantly by two determined little hands that are getting to grips with the world. There have been some experiences that are more surprising than disturbing too. Recently, while visiting my baby’s fatherland, I was panting uphill into the blaze of the Middle Eastern sun, baby strapped to my front. A car rolled down the hill slowed, the window was wound down and a shout of “Mazal tov!” came from a stranger inside. In my previous life, I never experienced anything like this. The nicest thing that had happened to me until then was probably when someone complimented my eyebrows, but it was marred by my memory of the Seinfeld episode in which George squawks, “Who cares about eyebrows?!”

Nowadays, people sweet-talk to me (via baby) in the street all the time. A bus driver smiled at me (her). Supermarket staff have cooed. “At THAT age they’re lovely,” the person sat next to us on the bus will say, no doubt cognizant of the horrors to come. Every day I see the softer side of humankind. Cynicism is clouded, if only for a passing minute. “I always said I’d never do baby talk,” a friend, father to a one-year-old daughter, told me, as he bounced my daughter on his knee goo-ing and gaa-ing. “Well, here I am…”

The daily experience of watching my daughter’s chubby wide-eyed face staring in sheer fascination at the world around her—rustling leaves, a plastic bag, a running tap, an annoying dog that I would really rather did not lick my ankle—chips away at the cynic in me. Her hearty laugh at random things, and her instinctive cry at others, will melt my heart quicker than the heatwave liquefies armpits on the Tube at rush hour. The way her little fingers examine anything with equal wonder makes life look interesting and innocent again. It’s like being with someone who is constantly on mushrooms.

Being pulled into the present with this wee thing who has no sense of the future has changed how I look at human creativity. I took the baby to see an installation of Ron Arad’s at Gordon Gallery in Tel Aviv. I would normally have had no tolerance for the work. The moment I stepped into the gallery, I was flooded with disappointment and thought it was a bit shit: the show was comprised mostly of one large installation of wavy mirrors, some of them positioned as tables on the floor, some mounted on the walls, the negative space carved between them creating a maze-like path to different positions from which the reflections looks different. Self-conscious, basic selfie-art, I would have thought—if I wasn’t there with a six-month-old baby who was enthralled, waving her little arms around. The reflections, unfamiliar movement and strange shapes brought her very new senses unprecedented joy.

Certainly, when I go to an exhibition now, I approach it differently, from the architecture up. Does it have stairs? Will it be crowded? Will there be a massive echo if—as she did at the Royal Academy recently—she starts to shout? Is there somewhere to deal with a poonami, should it occur? But it’s not only the practical matters that affect my gallery-going these days.

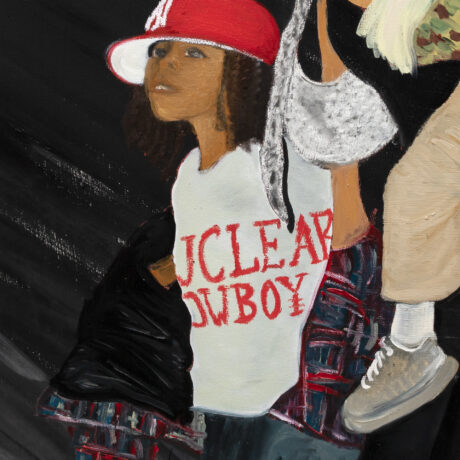

Back in London at the Whitechapel Gallery, I found myself again spending time with a work I would previously have skipped at the Whitechapel Open. I was drawn to Elisabeth Tomlinson’s female gaze on the black male body in her video trilogy William Series. I was enjoying Relic 1, an instalment of Larry Achiampong’s ongoing series, starring his own son, Sinai, when the baby woke up. Too bitesize for the headphones there, we wound up in the big, noisy, four-screen HD video installation by Tom Lock called Within. With its moving blobs and surround sound, coming at us in the semi-dark, I wondered if it reminded her of being in the womb. Her review was to blink a lot and stare.

Being analytical is highly valued in our society. It’s considered necessary for a cultured, civilized community. But often, as we sharpen our critical faculties, we blunt our senses and nullify our basic needs. The more you see, the less you feel. Many people won’t agree, but I think art is psychological. It is instinctive. In art, we see the world, as Anaïs Nin wrote, not as it is, but as we are. If we go back to our primitive version, our fundamental selves, in possession of little more than our senses and still not in control of those, art would look very strange, but maybe it would be more fun. I associated cynicism with strength. Now I find that stultifying.

One day, probably, my daughter will have her own cynical thoughts. In the meantime, a message to all the haters at heart: try taking a baby to a gallery and let them be the judge.