Juno Calypso, A Modern Hallucination, 2012

Juno Calypso knows a thing or two about the creative potential of domestic interiors—particularly if she is left home alone. As she explains: “I was always better at taking pictures when I was alone, so self-portraiture was my only way around that. It was still a private thing for a very long time—an offshoot of the kind of pictures you’d take of yourself in your bedroom as a teenager.” The British photographer’s eye for pastel hues, darkly humorous compositions and unsettling glamour has whisked her far beyond teenage selfie territory, but her focus on the role of women in the home remains a stalwart. Shot in her grandma’s bedroom, A Modern Hallucination takes its title from Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth, and develops ideas around a woman paralysed by her obsession with self-improvement and the artificial construct of femininity.

Do Ho Suh, Toilet, Apartment A, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA, 2013

The home goes handcrafted with Korean artist Do Ho Suh, who takes a deeply personal approach to everyday interiors. From a full-scale replica of his childhood home, which visitors can walk within, to smaller details that would otherwise be overlooked, light switches, sinks and even a detailed rendering of a toilet are brought to life by his deft hands. His use of translucent fabric is suggestive of the “invisible memories” of our daily experiences at home, bringing them into focus in bright monotone shades of blue, pink, orange and countless other colours. Suh has lived in London, New York and Seoul, and his scrutiny of his intimate surroundings reflects this nomadic existence, as does the fact that these sculptures can be folded down after exhibition and packed away into a suitcase.

Andy Warhol, Sleep, 1961

A silent film showing nothing more than a young poet sleeping might not sound like much, particularly in the age of TikTok videos that depict every last inane detail of our lives, but Andy Warhol’s early foray into the possibilities of cinema remains radical. With its simple concept and intimate subject matter, featuring Warhol’s lover at the time John Giorno, it takes a journey into the psychological space of the bedroom. With every rise and fall of his sleeping chest, we are lulled into a state of near-hypnosis—one that is amplified by the durational nature of what Warhol termed his “anti-film”, measuring an eye-watering five hours and twenty minutes in total. If you can stay awake, it is an experience that you won’t forget.

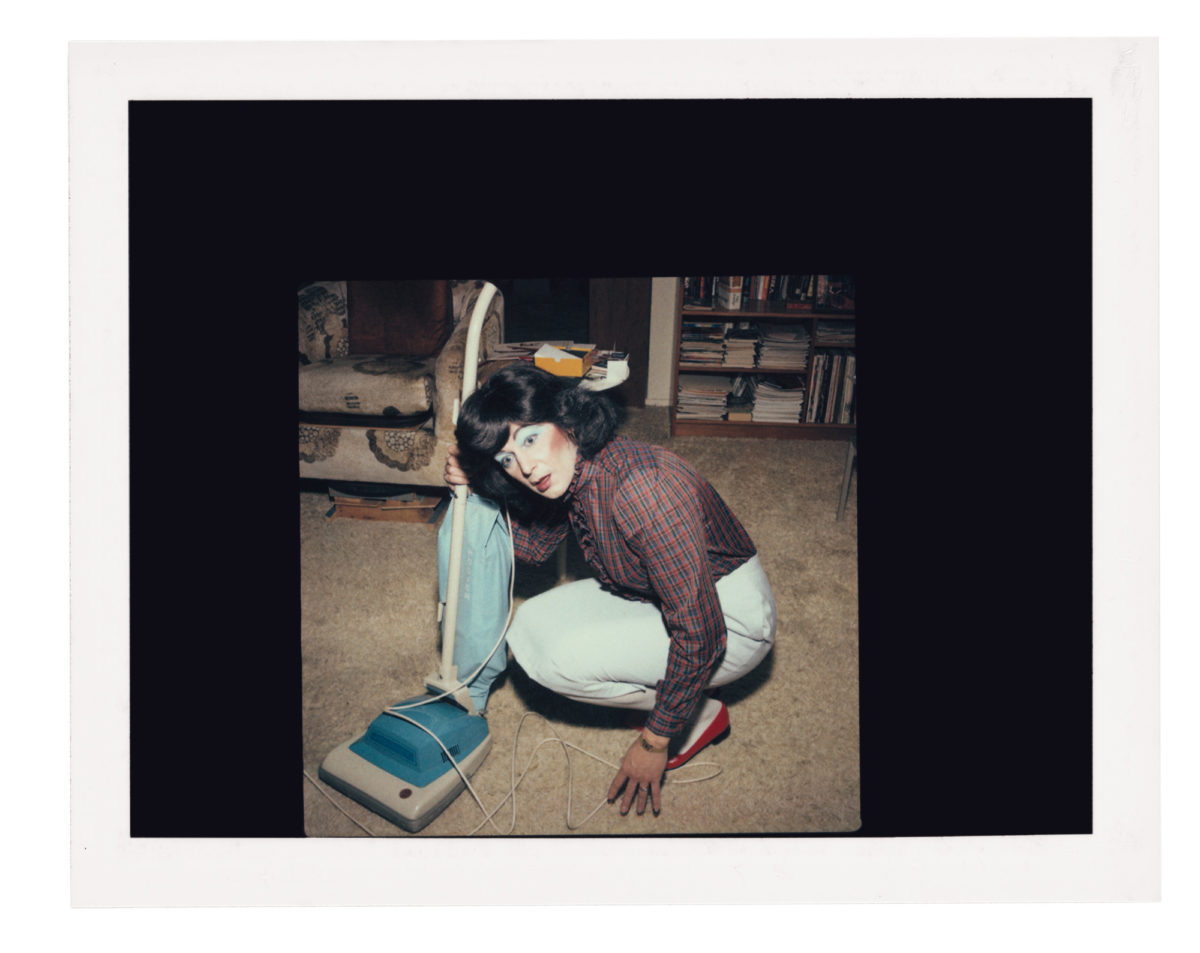

April Dawn Alison, Untitled, Date Unknown

For April Dawn Alison, the female persona of a California-based photographer who lived in the world as a man, the transition between exterior and interior, and between public and private, was sharply defined. In self-portraits taken over a thirty-year period, April reveals herself in the seclusion of her home, posing for the camera amidst the domestic setting of a cluttered kitchen, a carpeted living room or an ordinary hallway. Within these four walls, April Dawn Alison was born. After their death, over 8,000 Polaroid pictures were found by chance by a house clearance team, and later donated to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The self-portraits capture a life lived out-of-view in the privacy of the home, and reveal a rich inner life filled with as much humour as pathos, and as much joy as loneliness.

Gordon Matta Clark, Splitting, 1974

How do you cut a house in two? New York artist of the avant-garde Gordon Matta Clark, who trained as an architect, attempted a series of “building cuts” during the 1970s, carving out sections of entire structures in order to transform them into spatial compositions that he called “anarchitecture”. In the film Splitting, he documented his decisive slice into a New Jersey home slated for demolition, showing the hard, messy work behind the striking division of the house, whereby the building was bisected to allow light to flood into the usually dark centre of the domestic space. Matta-Clark invited visitors to see the result firsthand, although to venture inside the destabilized house was at their own risk, as it teetered on a temporary structure before finally being torn down.

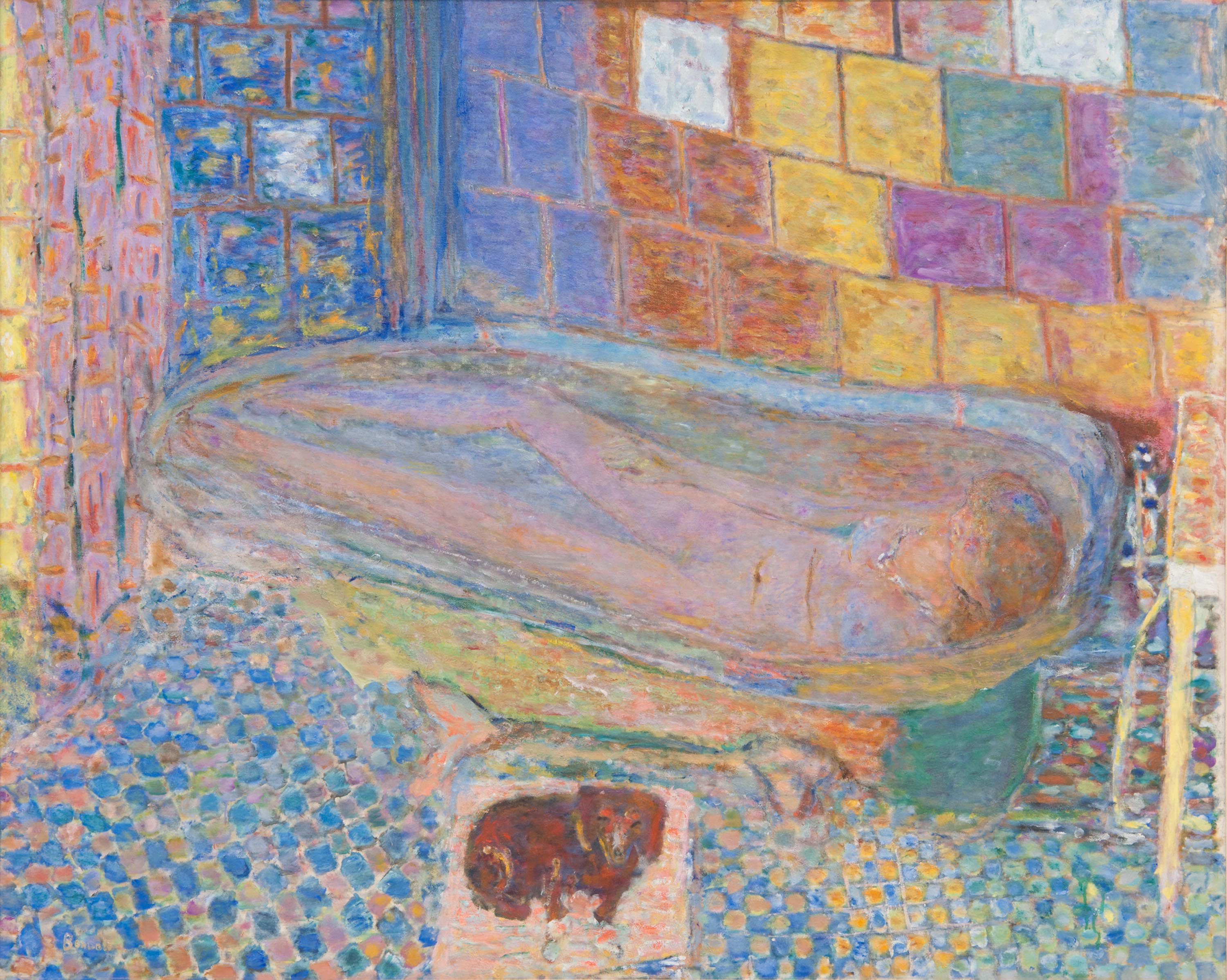

Pierre Bonnard, Nude in Bathtub, c.1940-1946

Bonnard had a knack for capturing the life of a room and the fleeting encounters that take place within it, rendering them in evocativ, dappled colours. In a series of paintings he turned his focus to the bathroom, a private space rarely depicted in paintings of the time. Bonnard’s wife, Marthe de Méligny, can be seen lying in the bath, offering a glimpse of an introspective moment of calm. But there is a darker undercurrent at play here, as bathing was a form of therapy for tuberculosis and hints at her ill-health. Infused with sunlight that bounces off the colourful tiled floor, there is a dreamlike, uplifting quality to the image as it offers a reminder of even the smallest pleasures of the everyday.

The Beach Boys, In My Room, 1963

The Beach Boys might be best known for their good vibrations, but they could pen a more sombre number on occasion too. “In My Room” captures a quietly reflective side to the group, and was written by Brian Wilson after he experienced a period of agoraphobia. His lyrics shrink an entire world down to a single bedroom, and recall the teenage compulsion to shut the door and allow the worries of school, parents and young love interests to melt away. As Wilson described in the 1998 documentary Endless Harmony, it’s about “somewhere where you could lock out the world, go to a secret little place, think, be, do whatever you have to do.”

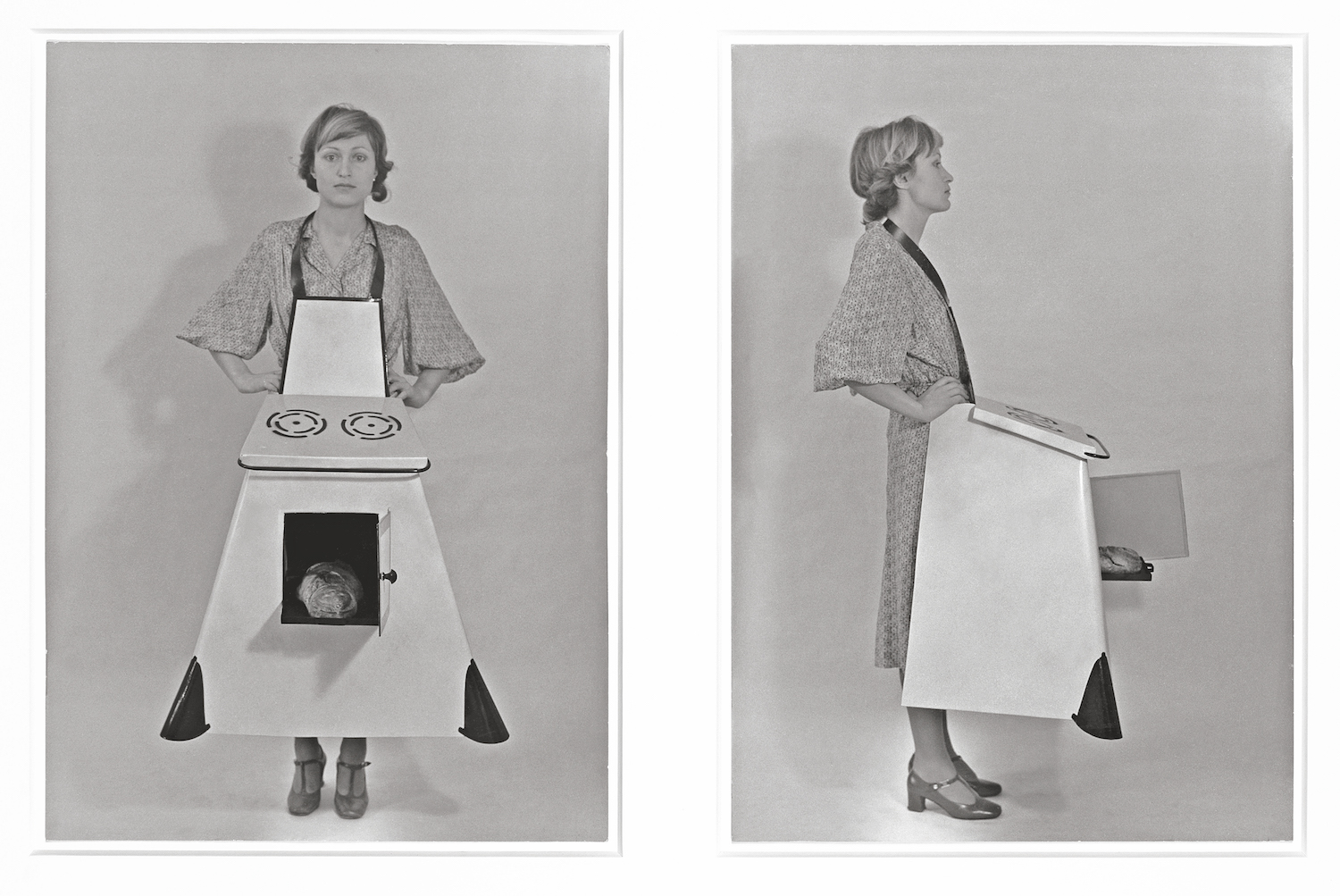

Birgit Jürgenssen, Housewives’ Kitchen Apron, 1975

An oven strapped to a female body sends a clear message, and Birgit Jürgenssen’s sharp and humorous work around gender roles and identity doesn’t mess around. The Austrian artist was part of a group of feminist artists prominent during the 1970s who carved out space for conversations around women’s issues, challenging the rampant sexism of the time. She used striking visual cues to make her voice heard; in Housewives’ Kitchen Apron, she photographs herself with a loaf of bread in the oven, a direct reference to female freedom of choice when it comes to pregnancy and abortion. Pointedly situated within the kitchen, it raises questions about female domesticity and entrapment.

Joanna Hogg, Exhibition, 2013

Before Bong Joon-ho’s surprise Oscar-winner Parasite, set almost entirely in an upper-class home in Seoul, there was Exhibition. The real star of Joanna Hogg’s film is the house in which it is set, as many critics have commented. It is ostensibly a portrait of an unhappy marriage between two privileged artists, played chillingly by Viv Albertine, the former lead singer of The Slits, and Liam Gillick, a real-life artist once nominated for the Turner Prize, but the house that they inhabit is never far out of sight. The two live in a modernist home in West London, featuring an impressive spiral staircase, numerous sliding doors and even a lift. The camera contrasts long, static shots of these artful interiors with glimpses of the outside world, as seen through slatted blinds, until interior and exterior become entangled with the states of mind of the film’s self-absorbed protagonists.

Sarah Lucas, Edith, 2015

You know a Sarah Lucas sculpture when you see one. The domestic mingles with the erotic in her careful assemblages of bodies and furniture, where a single well-placed cigarette can be enough to signify a crisis in masculinity. The British artist has made a name for herself with her talent for suggestion, drawing out the bawdy and the abject from items as innocuous as a washing machine, an Eames chair or a toilet. Her work seems to swell with a suppressed laugh, but it is left up to the viewer whether they ought to allow themselves a smile or a cry. Female breasts are revealed in stuffed and lumpy tights, and her preference for egg yolk yellow throws up multiple possible readings, from school canteen custard to sunshine through the kitchen window.