Eloise Hendy speaks with artist and president of the Royal Academy about her duties as both, and more specifically, her new show titled ‘Tracing Time’ at London’s Huxley-Parlour.

When I meet Rebecca Salter at the Royal Academy at the end of August, I don’t know it’s her first day back at the helm of the institution, after a month in her studio. What I do know is it’s the hottest day of the year, and along Piccadilly everyone looks frenzied, or as if they are wilting. Salter, on the other hand, arrives in the lobby like a breath of fresh air, in a soft monochrome outfit, with streaks of black painted through her cropped white hair. Usually I wouldn’t remark on an artist’s ‘look’ – especially in the case of so-called ‘women artists’ who are all-too-often hemmed in by their appearance. But I can’t help myself in Salter’s case, because, as we choose a spot to sit outside in the courtyard, it strikes me how much she looks like one of her own artworks: all monochromatic contrast and considered abstraction.

Salter has been President of the RA since December 2019. Stepping into the role, Salter stepped into history in a way none of her predecessors had. She is the first female President in the RA’s 251-year history. No pressure, right? “It’s a very difficult one,” Salter says frankly. “I mean, whoever you are, you don’t want to screw up being the president of the Royal Academy, let’s face it,” she laughs. “But there is additional pressure as the first woman, because, well, we know the conversation.” She pauses briefly, then reels off the kind of criticism she imagines could attach to her tenure: “‘She couldn’t take the pressure, she couldn’t do it’.” If this burbling pressure wasn’t enough to deal with, a couple of months into Salter’s stint, the pandemic happened. The RA closed its doors, without knowing when they might open again. “We were losing a million pounds a month,” Salter declares. Four years later, the institution is still experiencing aftershocks. “Things are still difficult,” Salter says, “because audiences – for all of the venues in London – haven’t come back to pre-COVID levels, so we all have to look at different models”.

The pandemic was a sharp introduction to being Presidenton a personal level too. “I learnt an interesting lesson very quickly about leadership,” Salter tells me. “During Covid, we had security staff in here 24/7,” she says. “At the time, the exhibition we had on was Picasso and Paper. It was worth I don’t know how many gazillion pounds, so there was no way we wanted a pipe to burst or anything like that!” Salter’s eyebrows jump at the thought. “So every Saturday morning, the Chief Executive and I would cycle in,” Salter recalls. “We’d bake cakes and have cups of tea with the security guys. And I think it was the second Saturday I arrived, and weeds had grown up between these limestones,” she says, pointing to the centre of the courtyard in front of us. “I thought that’s a message, isn’t it? The world’s fine without us.” Salter smiles. “So I go in and say, ‘there are weeds all over the place. They’re growing through the courtyard. How incredible’. Of course, because I’m the President,” she continues, in a tone that seems to draw quotation marks around the title: “I mean, there’s me, Miss Naive. I loved them. But by next week they’d gone. I think everybody thought, ‘the President doesn’t like weeds’, and they’d gone and pulled them all up,” Salter says, eyes wide in mock incredulity. “I learned a lesson,” she adds. “I thought, ‘OK, you’re President now, so you’ve got to be very careful what you comment on, because people won’t just take it as a comment’.”

It’s hardly surprising, hearing Salter skip from the major worry of funding, to the endearing concern with whether the security had enough tea, all the way down to the cracks in the courtyard’s slabs, that her artistic work often took a backseat during the pandemic years. There must not have been much time for her own creative practice, while she was down in the weeds. “It’s supposed to be three days a week,” Salter says of the presidential role, “but it isn’t really, especially not during COVID.” She realised she would have to set herself different parameters; come up with new tactics. “I really didn’t want to have so little time in the studio that all that happened was I’d go in and I’d do a small one, because I wanted to finish something,” Salter says. “And then I’d finish this job and I’d have a studio full of little postage stamps.” She smiles again, but I can tell this was not a minor concern. “I didn’t want to just have lots of little things, because that would feel as if my practice had been diminished,” she says carefully. “So, I deliberately made what would seem like a counter-intuitive decision to do the opposite, and do maybe one or two big paintings a year.”

It’s at this point she tells me this is her first day back. “I’ve just been in the studio for August,” Salter says. “If I don’t consolidate something over August, then once everything starts up, I haven’t got concentrated time to think through new ideas.” It’s clear it is this thinking that matters most to Salter. “Of course, you think the practicalities of being in the studio is the real problem,” she says softly, as if turning the question around in her mind, looking at it from a different angle. “The real problem actually is finding space in your head.”

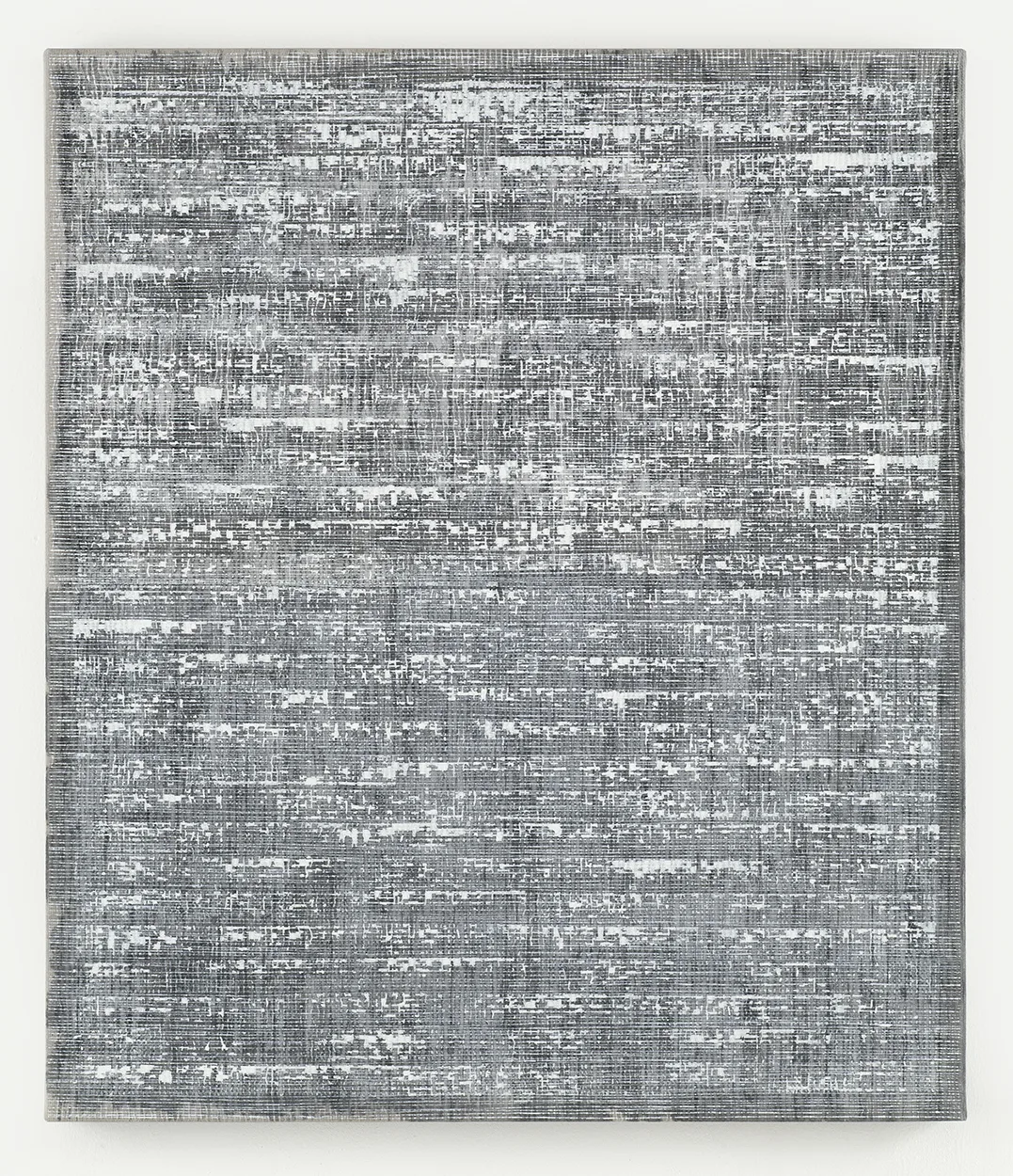

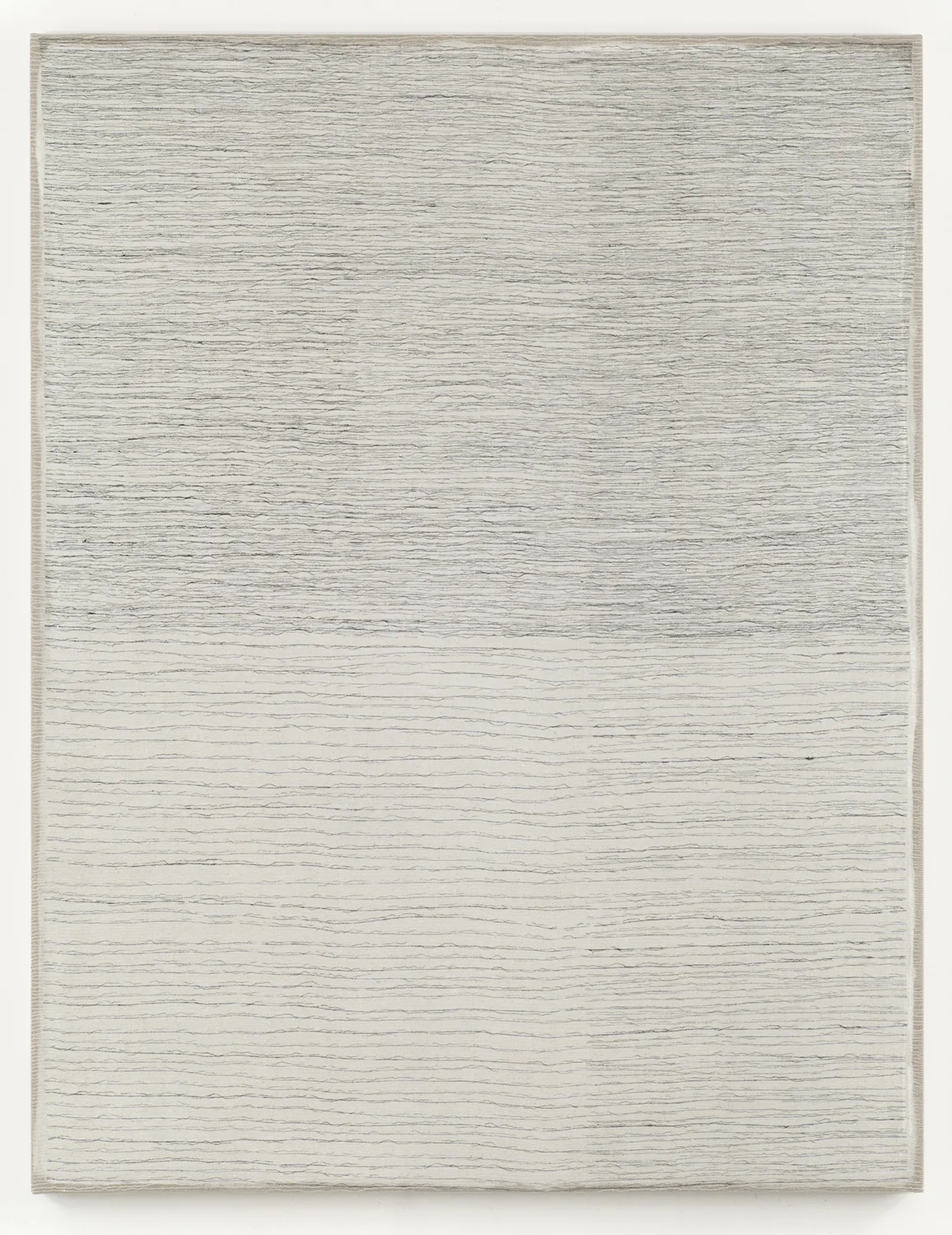

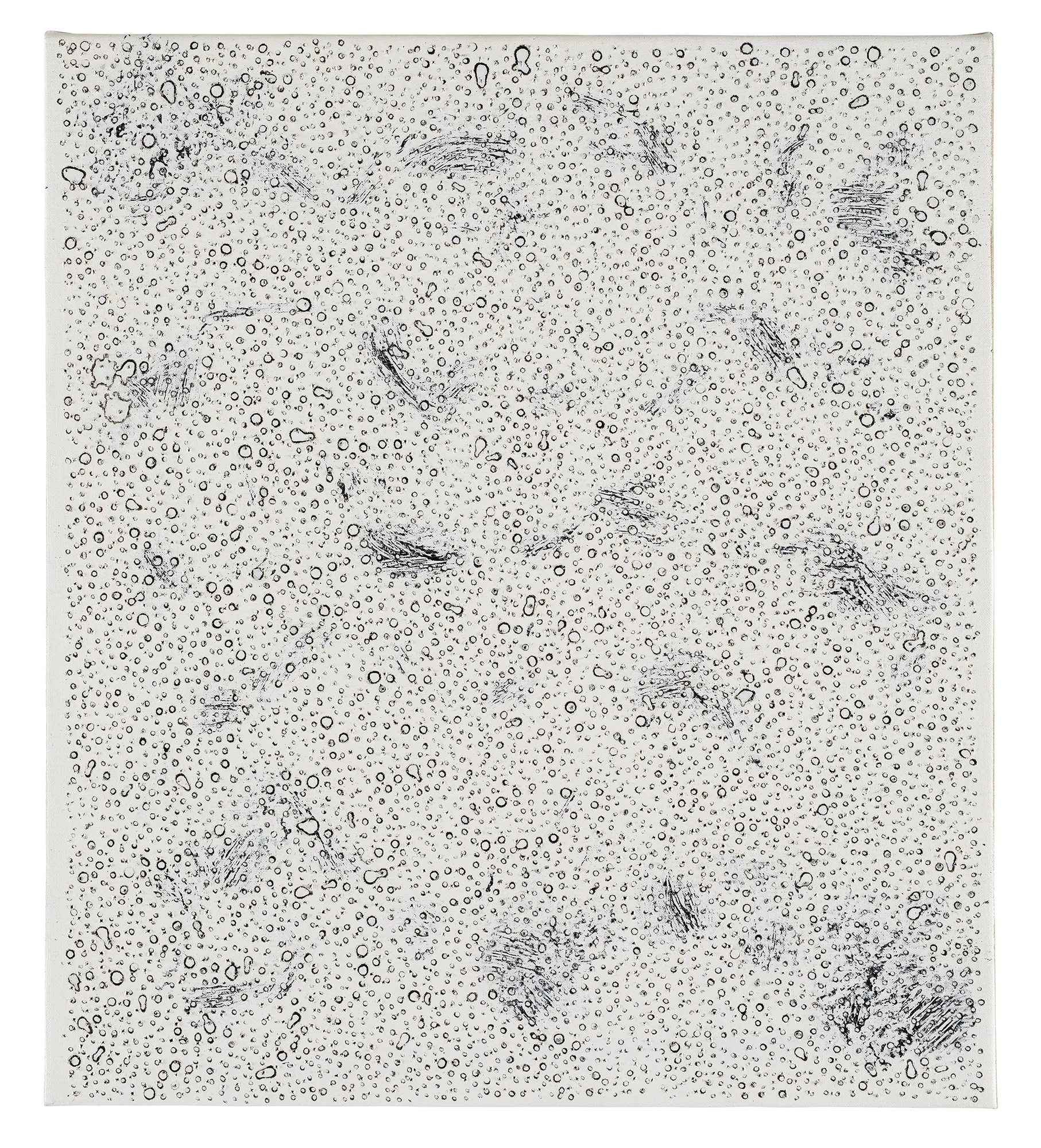

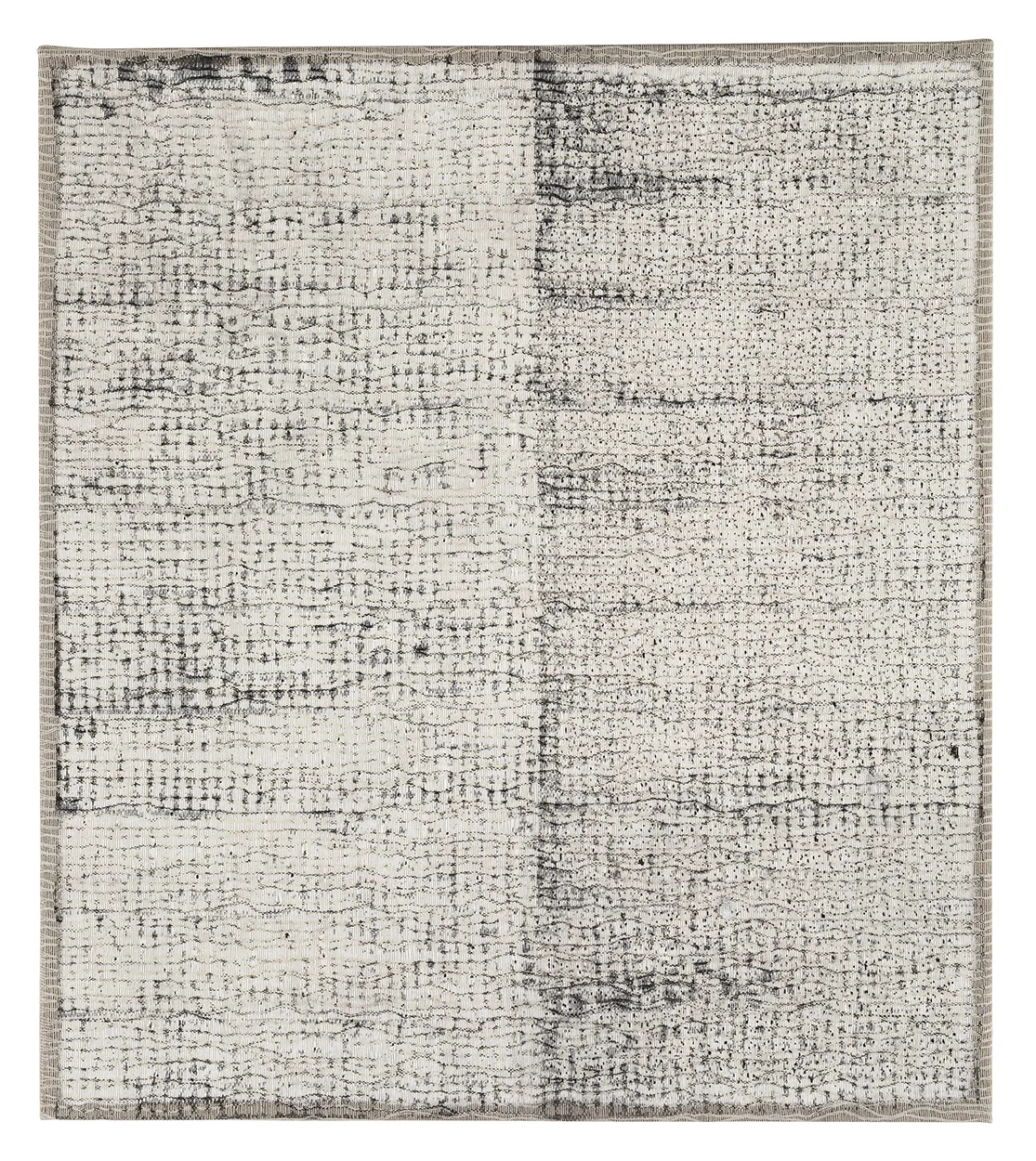

Yet Salter has, it seems, been pretty successful at making time and finding space. Enough, at least, to fill a new exhibition at London’s Huxley-Parlour – her first with the gallery, and her first solo commercial show in eight years. And there are not just “one or two big paintings,” but 19 works, all of which showcase Salter’s exquisite attention and experimental approach to material. Lines of ink waver across her canvases, or pool through layers of muslin and linen. Threads are painstakingly pulled apart to create patterns that sometimes look like rippling water, sometimes like mist, the bark of a tree, or the mysterious micro-universe of a petri-dish. All are untitled, except for a four-digit code: (AM02); (JA19); (AM24). These technical labels, which recall paint colours and chemicals, give the pieces a scientific air – a sense of having been honed to pure essence. This isn’t the only scientific resonance in her work. The paper Salter often uses allows thin paint to soak through, in a technique inspired by Japanese woodblock printing. “In this process,” the exhibition text declares, “the paper absorbs the materials laid onto it, altering its makeup and producing a molecular shift in the object.” Taken together, Salter seems not so much an artist, but an alchemist. It doesn’t surprise me to learn she often works in a white lab coat.

Yet, Salter insists there’s a practical reason for her technical labels. “When I first started showing, I was living in Japan,” she says, referring to a period in the early Eighties when she studied at Kyoto City University of Arts, before remaining for a further four years. “You’re immediately faced with this dilemma,” Salter says. “You think, ‘putting Japanese titles on would be pretentious because I’m not Japanese’.” She admits to having toyed with this idea initially. “Then I thought, oh, that’s not a good look really! So I’m not going to do that. But if I go and call it, ‘Sunset over Shoreditch’, all the Japanese people are going to go, what? So I just went down a very practical and very boring route.”

I can’t help laughing with her as she says this, because I can’t imagine anyone finding either she or her work “boring.” Indeed, the word that’s used most often in relation to Salter’s work is ‘meditative’. “Meditative is interesting,” she says, “but I’m actually very interested in repetition, because a lot of what I do is hugely repetitive. But it’s repetition with difference,” she stresses. “At the moment I’m doing thousands, not unlike this table” – she taps the flecked tabletop lightly with her fingertips – “millions of dots. But every dot is different, you see.” It’s an artistic process that, to outsiders, might seem like madness, she admits. “People often say to me, why can’t you just get a stamp or something,” Salter says. “Mechanise it. And you just think, well that defeats the whole thing.”

By this she means time itself. The title for the Huxley-Parlour exhibition couldn’t be more apt, for, as Salter says, “with a lot of the works, you can actually read time in it. When I come in again in the morning, inevitably the marks are slightly different,” she notes. “By the end of the day, they’ve changed again. I can think, yes, I started there yesterday, and now I’m starting here today”. The weather makes a difference too. “Things will dry really quickly,” Salter says. “Out of my control. You work into wet surfaces very happily when it’s pouring with rain in February and then the sun comes, you try to do the same thing in June, and it’s different.” She enjoys this unpredictability though: “I quite like the fact you have to go with that and say, okay, now it’s slightly different.”

Tracing Time is a perfect phrase for another reason too. “They do take a long time,” she says simply. Many of the exhibition works have muslin overlaid onto linen. “I’ve painted on the muslin first, and then I move the threads apart,” Salter explains. “Drawing with the thread, that takes months. Because you’re spending all day just with a sharp thing, moving the thread. But by doing that,” she adds, “you disrupt the lines that you’ve drawn.” In Japan, Salter tells me, there is a belief in “keeping the line alive”: “If you get too good at it, then the line dies.” So, at the moment, Salter is working on “a huge drawing” that she has done entirely with her left hand. “Because that means you have to actively draw, rather than with your right hand, where you can draw it and be thinking about something else”.

Again, it is thinking that is important, or perhaps more accurately, attention. “There is a read across between the time it takes me to make one, and the time, I hope, it takes people to find everything in them,” Salter muses. “Unfortunately, the world we’re in now everybody’s on a very short time scale,” she says, and I can’t help glancing out onto Piccadilly, where people push past each other in 33 degree heat. This reference to our fast-paced way of living seems to strike all the key elements of Salter’s work: time, attention, and materiality. “I have to keep making this gesture,” Salter says lightly rubbing her forefingers together, in what could easily be mistaken as the Western sign for ‘money’. “Japanese people make this gesture for materiality,” she explains. “The feel of something. And that is so completely lost if everything is screen based.”

Aware of the irony, Salter gets her phone out to Google the name of a Finnish architect she wants to reference: Juhani Pallasmaa, author of The Eye of the Skin and The Thinking Hand – two titles that could, in another life, work well for Salter’s works. “He’s an architect,” she says, “so they’re all about hapticity, texture and touch in architecture. But for me, it’s also very important.” By way of an example, she offers up an anecdote about her return to the UK from Japan, in 1985. “All the painting is on paper, everything is water based, so there’s a softness to the surface,” Salter notes. “You come back here, and you drop down to the National Gallery,” she says, her features taking on a faintly horrified expression. “It was the varnish I found really excruciating – that glossy, hard surface.” Rows of Rembrandts swim through my mind like a series of phone screens or skyscrapers. “I want a much more ambiguous surface,” Salter stresses. “Where does the surface meet the world? How do I get inside it?”

It is this urge to really “get inside” the work that means, for all the control and care Salter clearly takes over each of her pieces, there is an alluring element of chance and surrender too. Indeed, at one point she describes her process as, “go straight in and see what happens.” Hers is an art of precision, which allows for accident. “There’s a feeling that the seed of the next work comes from an imperfection,” she says lightly. “In whatever painting you do, there will always be a bit where you think, ‘damn, that’s not quite right’. But, rather than resolving it, you allow that to exist because that is the seed of the next work.” This desire to work against resolution strikes me as a similar urge to that of drawing with her left hand. “You acknowledge that this work is finished, but it’s not perfect,” Salter adds. “It’s that that’s going to give rise to the next one. And it’s going off into the world, taking that seed of the next work with it.” Salter’s face is almost wistful for a moment, then she breaks into a grin. “It all sounds terribly romantic and a bit over fluffy when you say it!” Perhaps she’s right. But, as we say goodbye, and I cross the courtyard towards the urban heat, I find the notion moving. I think back to Salter’s fondness for the burst of weeds, her desire to allow those to exist too, and it seems like a fitting metaphor for art making – seeds sprouting from unlikely places, growing between the cracks, in whatever space they can find.

Words by Eloise Hendy