It starts with the patter of rain, swelling thunder, bells tolling, the night made audible. And then a crash: distortion’s white heat, a plaintive wail, dissonance, bass charging, a plea for redemption.

Heavy metal emerged fully formed in that moment in 1969, on the opening track of the first LP by an emerging group from Birmingham, an industrial city in England’s West Midlands. All three—song, album and band—were named Black Sabbath.

The music felt like a reflection of the environment that its creators grew up in. “It was quite a bleak place,” says arts producer Lisa Meyer. “Their fathers had worked in factories, and they knew what life was set out for them.

“Their fathers had worked in factories, and they knew what life was set out for them”

“In Park Lane, where [guitarist] Tony Iommi grew up, you had small factories right next to domestic housing—it was all part and parcel of growing up in Birmingham. So that shaped the sound, the combination of heavy industry and wanting to escape from that.” The sound was an early influence on Meyer, whose projects have ranged from organizing experimental music festival Supersonic to producing exhibitions exploring metal’s impact on visual culture.

Alongside the saturated audio came lyrics that referenced occultism and the supernatural. “There’s that fantasticalness in terms of the imagery and the lyrics, but when people think about the darkness of it, the darkness isn’t necessarily around Satanism—it’s the darkness of real life, the heaviness.

“At that time you had books by people like Dennis Wheatley, and Hammer Horror films. They were a form of escapism, taking you out of the ordinary. And at the same time, there were the anti-Vietnam war demonstrations. If you think about the lyrics of [Black Sabbath song] War Pigs, they’re about real-life horror, as opposed to the more the fantastical sense of horror and escapism.

Jump forward half a century, and what began as an isolated response to life in the West Midlands has become a worldwide phenomenon, with bands and devotees in their millions spanning from Chile to North Korea, California to Jerusalem. Yet in the city where it all started, acknowledgment of that is hard to come by.

- Home of Metal at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Exhibition View © Home of Metal

“Running Supersonic festival, I was putting on experimental bands like Godspeed You! Black Emperor and Sunn O))),” says Meyer. “They were coming to Birmingham and saying, ‘this is the home of Sabbath and Napalm Death, what can we go and see?’ And there’s only an empty shop that used to be a famous club, or a car park that was an amazing venue in the sixties. It felt like there was nothing to pay homage to.”

In the absence of a focal point in the region, Meyer organized Home of Metal, a season of exhibitions and events celebrating the region’s most enduring export on the fiftieth anniversary of its birth. “We started the project in 2007 with a number of artists including Mark Titchner. We were looking at how metal culture and the aesthetics of metal had permeated beyond the music and into contemporary visual arts and fashion. It spawned from Birmingham, and yet it’s become something so much bigger.”

Alongside an exhibition at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery celebrating Black Sabbath, this season brings together a number of shows exploring the genre’s broader impact on visual culture. Foremost among these is a group show at the nearby New Art Gallery Walsall titled Four-Bed Detached Home of Metal, organized by British artist Alan Kane.

“I chose to wilfully misunderstand the brief slightly and be very literal with the idea of the home, very literal with the notion of metal,” says Kane. “In a way I’ve made a fictional character who is the dweller in this home, and then played with the idea of what might have been of interest to that individual.”

The show brings together pieces by artists including Sarah Lucas, Jeremy Deller and Kane himself, alongside works created by “citizen artists”—members of the community who collaborated with Kane to create installations in the form of bedrooms within the exhibition space.

The collaborative installations are a surprise highlight of the show. “The impact of the fans’ bedrooms is pretty dramatic in my view,” says Kane. “They stand up as an experience with any other work in the show, and that was not necessarily something that I thought would be easy.”

While Kane is no fan of the genre (“I saw Black Sabbath when I was quite young but it wasn’t a particularly earth-shattering moment for me”), he was attracted by the creativity it inspires in its devotees. “I keep coming back to looking at where that impetus for making art comes from. Heavy metal is undeniably a huge source of creative energy, creativity like you might expect to see in an art gallery all over the world. Creative energy in that volume can’t really be overlooked—it’s a significant global force.”

“One way to look at my work is that it’s not just mine, it’s all of ours, as a community”

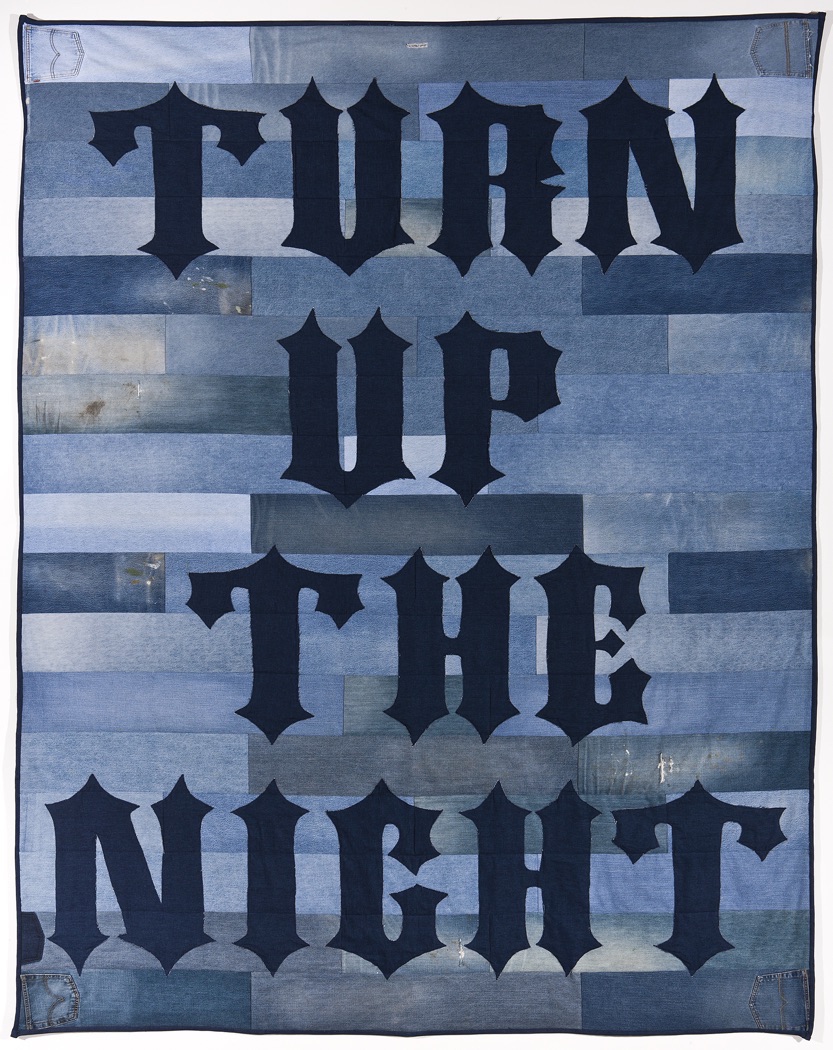

Overseas, American artist Ben Venom’s practice was shaped by his participation in Atlanta’s punk and heavy metal scenes. “I grew up listening to heavy metal music from a very early age, and that never left as an interest for me. As I started making artwork, I was influenced by the designs, the aesthetic, the mystique of heavy metal.”

Drawing on the do-it-yourself attitude of the punk scene and the sense of a broader metal community, Venom creates textile pieces and clothing from patches of donated materials. “The community aspect is very strong. Sometimes people send me boxes of clothing that I cut up, and that becomes my artwork. One way to look at my work is that it’s not just mine, it’s all of ours, as a community.”

“In part, Venom was attracted to metal by its aesthetic of excess: I was always drawn to the over-the-top mentality: go big or go home.” For All This Mayhem, his exhibition at Midlands Art Centre

, Venom has taken this approach to extremes, creating large-scale works featuring phrases and imagery drawn from the music. “The centrepiece of the show is a quilt called See You On the Other Side. It’s the biggest I’ve made to date. That was made within that idea of trying to go big.”

For Venom, the global reach of the genre is testament to the depth of feeling that it inspires. “It really speaks to the power of heavy metal music—it’s influenced so many different types of people. In Botswana there are people who dress up as heavy metal cowboys. When you have a band that’s formed in Baghdad playing heavy metal music, they can literally lose their lives by doing that. That’s the ultimate dedication—you’re potentially at risk of losing your life, but you’re so into this particular musical genre that you don’t care, you say fuck it and go all the way.”

For Kane, too, the universality of metal’s appeal speaks to something fundamental. “There must be something about it which is human, rather than individual. It is quite camp and theatrical, and that’s a universal attribute that might appeal globally. It’s not something you could pin down to being a fashion thing—it must be deeper than that.”

Meyer feels that this global force, a movement that speaks to something fundamentally and deeply human, has been underappreciated in its home country for too long. “For me this is a stepping stone towards creating a permanent collection or museum that celebrates this musical culture. It’s important for me that this isn’t a one off. This is sticking a stake in the ground to say look, there are the people, there’s the audience. This is something that we should embrace.”