A few dozen people crouch on a lawn, curled into pebble-shaped balls. As you draw near the closest one, she steadily moves to a standing position, pulls out a mask from her pocket and puts it on. And then she walks over and regales you with a story.

This is one of the central works in Tino Sehgal’s summer exhibition in the grounds of Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. Sehgal’s artworks, which he calls “constructed situations”, hinge on encounters between singers, dancers, storytellers and an audience.

They have long had the power to startle: 2012’s These Associations was the most unforgettable work to fill Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in the last decade. But this year the Berlin-based artist’s work carries a new charge. After months of isolation, even talking to a stranger feels liberating.

The pandemic lacerated artists and art institutions the world over (with the exception of a few auction houses and blue-chip galleries). Live art was hit with particular keenness. “It stopped it in its tracks,” says live art curator Rose Lejeune. “The central tenet of performance art, bodies in spaces, became dangerous, something to fear.”

In many countries, live art was banned outright. Artists and organisers faced closed venues, cancelled programmes, postponed funding schemes: an mammoth threat for a field that often relies on ticket sales and grants to survive.

Covid-19 remains. But in some countries at least, live art has begun to return. In London in August 2021, Lejeune organised Performance Exchange, a weekend of live artworks held at private galleries in the city (it had originally been planned for 2020). When I visited on the Saturday, the early evening audiences crowded outside Belmacz gallery in Mayfair watching a piece by Sadie Murdoch and Abbas Zahedi, contending with angry chauffeurs leaving the nearby Claridge’s hotel.

“The central tenet of performance art, bodies in spaces, became dangerous, something to fear”

Earlier, at Sadie Coles HQ, a work by Darren Bader saw a five-piece brass band attempt to pop corn through music (though neither they, nor a bagpiper who came in part-way through, succeeded). Standing in an informally distanced crowd listening to the glorious racket was thrilling.

“The response to it was incredible,” says Lejeune. “I think people have missed that kind of live interaction. It’s a physical experience.”

Many restrictions remain. At the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, German performance artist Anne Imhof’s Carte Blanche exhibition opened without any live performance. Performance Exchange was originally going to feature international galleries and artists, but ever-shifting rules necessitated a London-focused programme.

“Travel feels like it’s the very last piece of the jigsaw puzzle to me,” says Lejeune. “It’s unclear how it’s going to work again, and some people are still pretty unwilling to travel.”

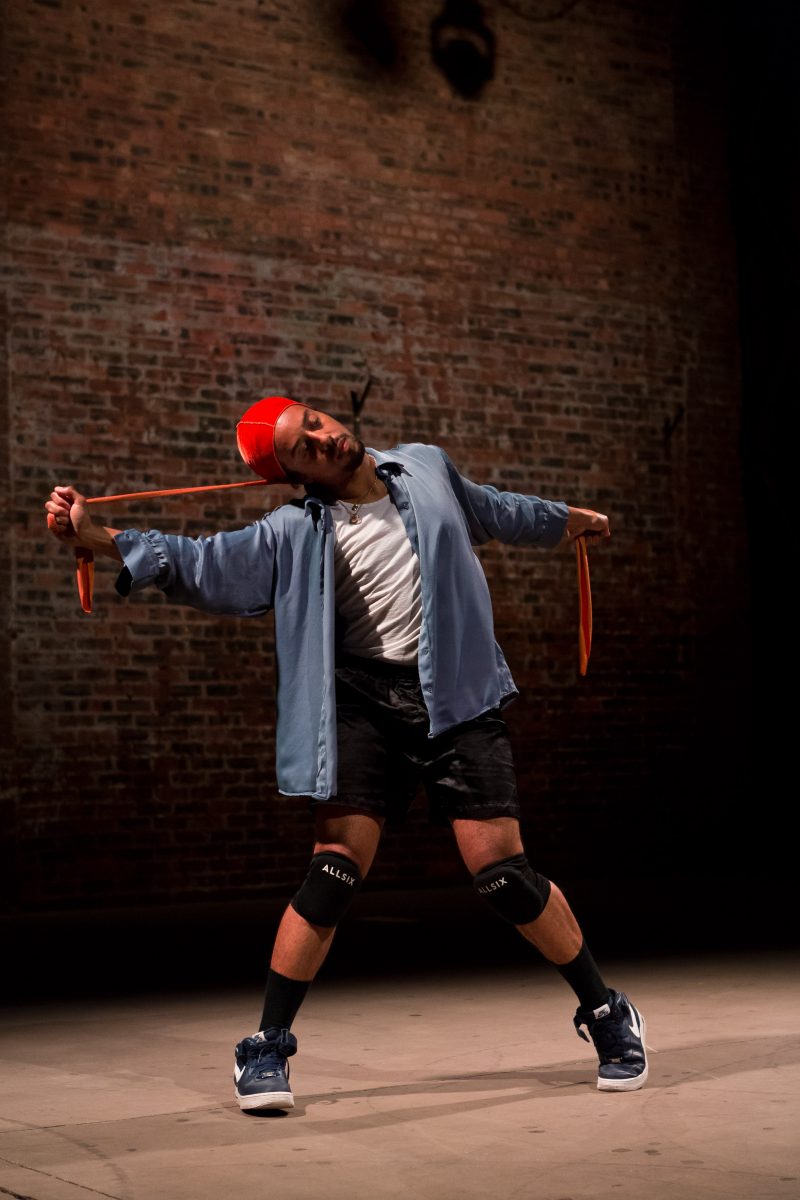

Restrictions can even pose a problem within a country. In June 2021, Paul Maheke performed his piece Taboo Durag at Glasgow International. The performance was organised by the Roberts Institute of Art (RIA, previously DRAF), a non-profit organisation which has supported performance events since 2007.

“It was particularly difficult for us,” says RIA’s director Kate Davies, “because Scotland has a different set of Covid restrictions. It was difficult working at a distance. Everything was changing so fast: we were actually releasing tickets to the public at a point when we were still not allowed to put the work on.”

With the help of the Glasgow International team and the venue SWG3, the performance went off without a hitch. Audiences were limited to 100 people, distanced across a large space. Some aspects of the piece had to be changed, including sections where Maheke would normally walk through the crowd, to meet regulations and ensure safety.

“It had people in tears… it felt so emotional, not only the nature of the work but just being able to see live work again”

“It was a huge challenge,” recalls Davies, “but luckily people did feel safe. And actually it had people in tears, I think because it felt so emotional, not only the nature of the work but just the fact of being able to see live work again.”

RIA’s next performance project is six commissioned works, which will be performed in London this December. They, too, were delayed a year. RIA’s Evening of Performances, previously held annually during Frieze week at high-capacity venues including Ministry of Sound, Kentish Town Forum and the Koko, remains on ice.

Davies explains: “You’ve got to take into account that there are still people who are vulnerable. You don’t want to exclude these people.” Such changes might not be a bad thing. “Maybe a loud celebratory environment,” Davies says, “isn’t always the best environment to show the nuance in work, and have audience engagement that is more personal and individual.”

The past year has had an acute psychological affect on many practitioners. “I feel like we’re still in the middle of processing what happened,” says Joseph Morgan Schofield, “and that’s the thing with this crisis and trauma.”

Schofield is co-founder of Deptford performance art space VSSL, artist development coordinator at Live Art Development Agency (LADA), and a practising performance artist himself.

“Although performance art in the UK is quite a broad church,” they continue, “there are communities within it. And I think that the communities are very active and very interwoven, and friendships and other kinds of interpersonal relationships play a huge part of it. Isolation meant that this whole kind of support network disappeared.”

The pandemic did not happen in a vacuum. At LADA, the murder of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement that followed prompted what Schofield calls “a necessary and very overdue reckoning with white supremacy.” The organisation underwent a process of review, emerging with new leadership and an embedded commitment to anti-racist values.

Other platforms reflected on the future of live art itself. Block Universe, an annual London-based live art festival, suspended its live programmes. Instead, it presented a newsletter, interviews with artists, and roundtables on how to sustainable present performance works in future.

The most widespread change was an embrace of the digital. This March, Serbian performance and conceptual artist Marina Abramović collaborated with the file-sharing platform WePresent to introduce her own work and that of five other artists online. At Performance Exchange, a number of people asked Lejeune whether its events would be live-streamed.

But artists were not only migrating online. Schofield saw “the incredible resourcefulness of artists who continued to find unusual or new ways of performing. Some works happened where maybe you weren’t actually connected to anyone at all, but things were happening at the same time in different places.”

Artist, dancer and choreographer SERAFINE1369, for example, has an exhibition at Tate Britain this September that will resemble a performance without a performer.

VSSL began staging performances as soon as private galleries were allowed to open in April. It began with a one-on-one work by Chinasa Vivian Ezugha. Then, when crowds were allowed to assemble outdoors in early May, it hosted a performance by Jasper Llewellyn on the shore of the Thames.

“We saw the incredible resourcefulness of artists who continued to find unusual or new ways of performing”

Once larger audiences were allowed indoors, the gallery exhibited a durational performance piece by EM Parry. “I was very anxious hosting,” recalls Schofield, “because you’re trying to help the artist to do the best work they can but also need to look after everyone’s literal health at the moment.”

Despite ongoing anxieties, some things have returned at least. Schofield recently went to London’s ICA to see Martin O’Brien’s The Last Breath Society (Coughing Coffin), a durational piece held over several days.

“It’s an amazing work looking at the temporality of death,” explains Schofield, “and that becoming paradoxically a celebration of life. There was a moment at the end where I had seen various people who I hadn’t seen for 15 or 16 or 17 months, including performance art elders, legends in our community. And even though we were all masked up and had to be quite distant, it felt so moving to be with those people having come through it all.”

Live art may not be back to normal, but it might be emerging from the fire with renewed power.

Joe Lloyd is a London-based freelance writer on art, architecture and photography