It is amazing that Glyn Philpot is not better known. The British artist blazed a trail as a young society portraitist at the outset of the 20th century, riding the modernist wave to capture the likeness of Bright Young Things, actors, aristocrats, and more.

Born into a middle-class family in Clapham in 1884, he left mainstream education at the age of 15 to attend art school thanks to a scholarship awarded on the basis of his impeccable draftsmanship. Early in his career, his devotion to the works of the Old Masters so dazzled the Royal Academy that he was elected as the youngest member of his generation, in what was seen as a celebration of his dedication to traditional formalism.

Yet, Philpot continually went through periods of radical reinvention, shifting to the avant-garde aesthetics of Art Deco and the sizeable influence of Picasso, while coding his works with personal connections to sexuality and religion. He also elevated the visibility of Black sitters, in a manner that was largely unheard of at the time. Even now, his paintings still feel strikingly contemporary, and at times even surreal.

“Philpot was what we would now term a gay, or queer, man”, says Simon Martin, director of Pallant House Gallery, where a new exhibition shines a much-needed light on the artist’s work. “These labels didn’t necessarily exist in the 1920s and 1930s, but we do see expressions of his desire through the work”.

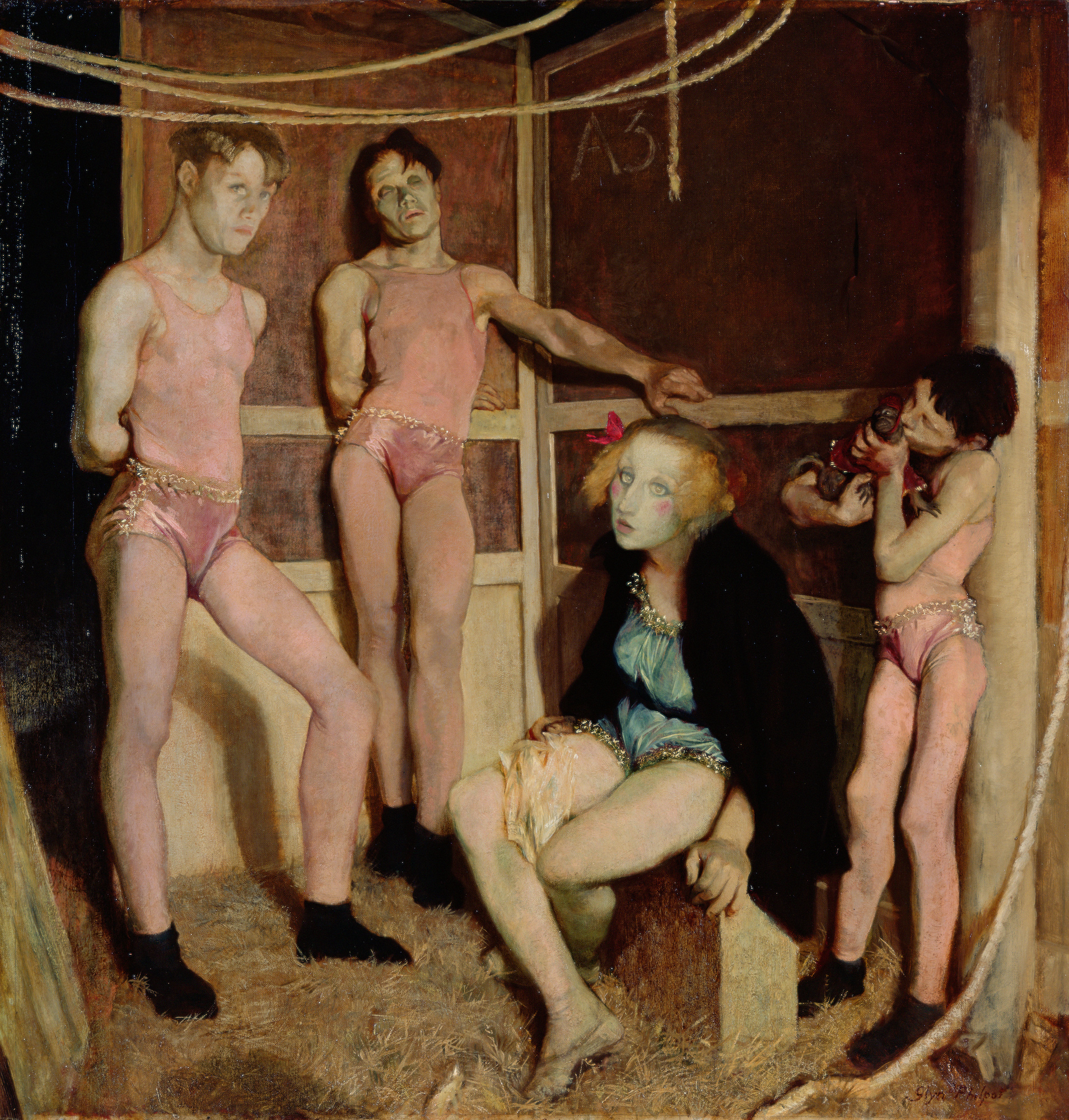

The primary desire, it seems, was indeed the male body. Beyond the society portraits, erotic nudes fill the exhibition. For example, in a reinterpretation of The Odyssey, the hero’s long-suffering wife Penelope is seen surrounded by three semi-clad suitors, one of whom was originally intended to be entirely naked, with chiselled buttocks, before Philpot reconsidered for fears of impropriety.

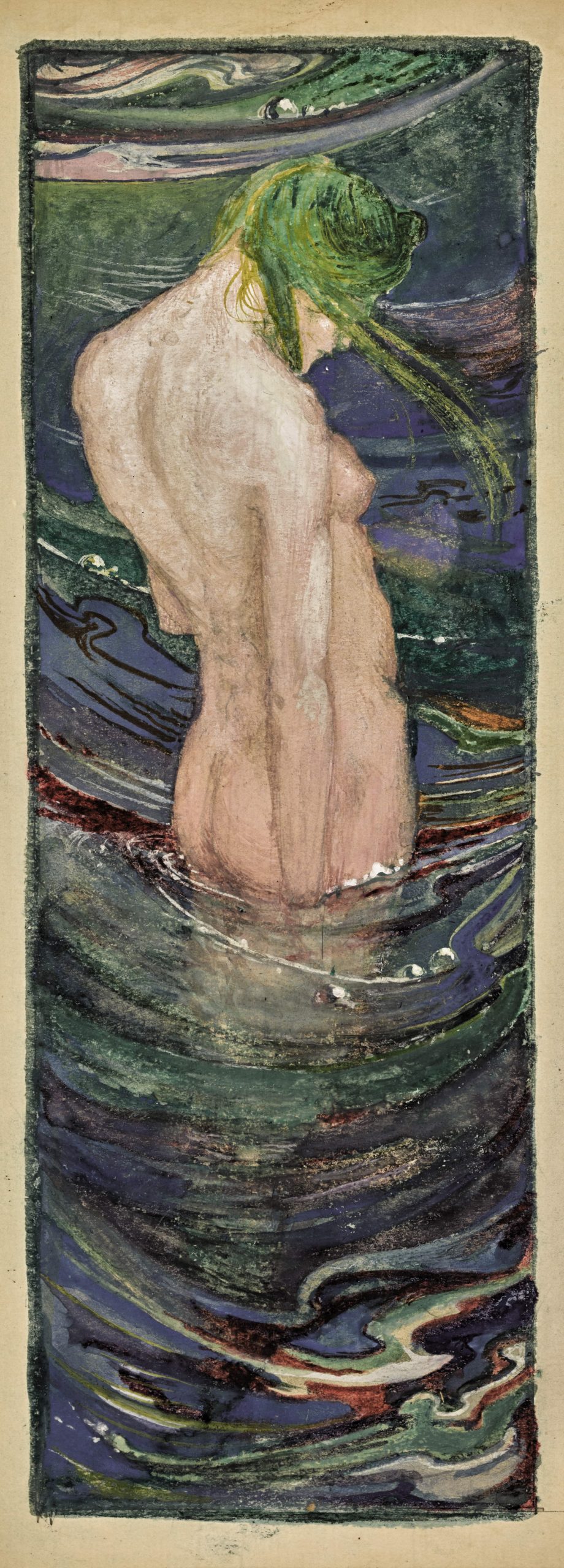

Elsewhere, he skates close to the edge of ‘acceptability’ in other ways. The androgynous watery visions seen in Two Figures Under the Sea

(1914-18) and The Mermaid (1902-03) play with gender binaries and feel fantastically sexually charged, alluding to the longstanding relationship between oceanic myths and eroticism.

“Even now, his paintings still feel strikingly contemporary, and at times even surreal”

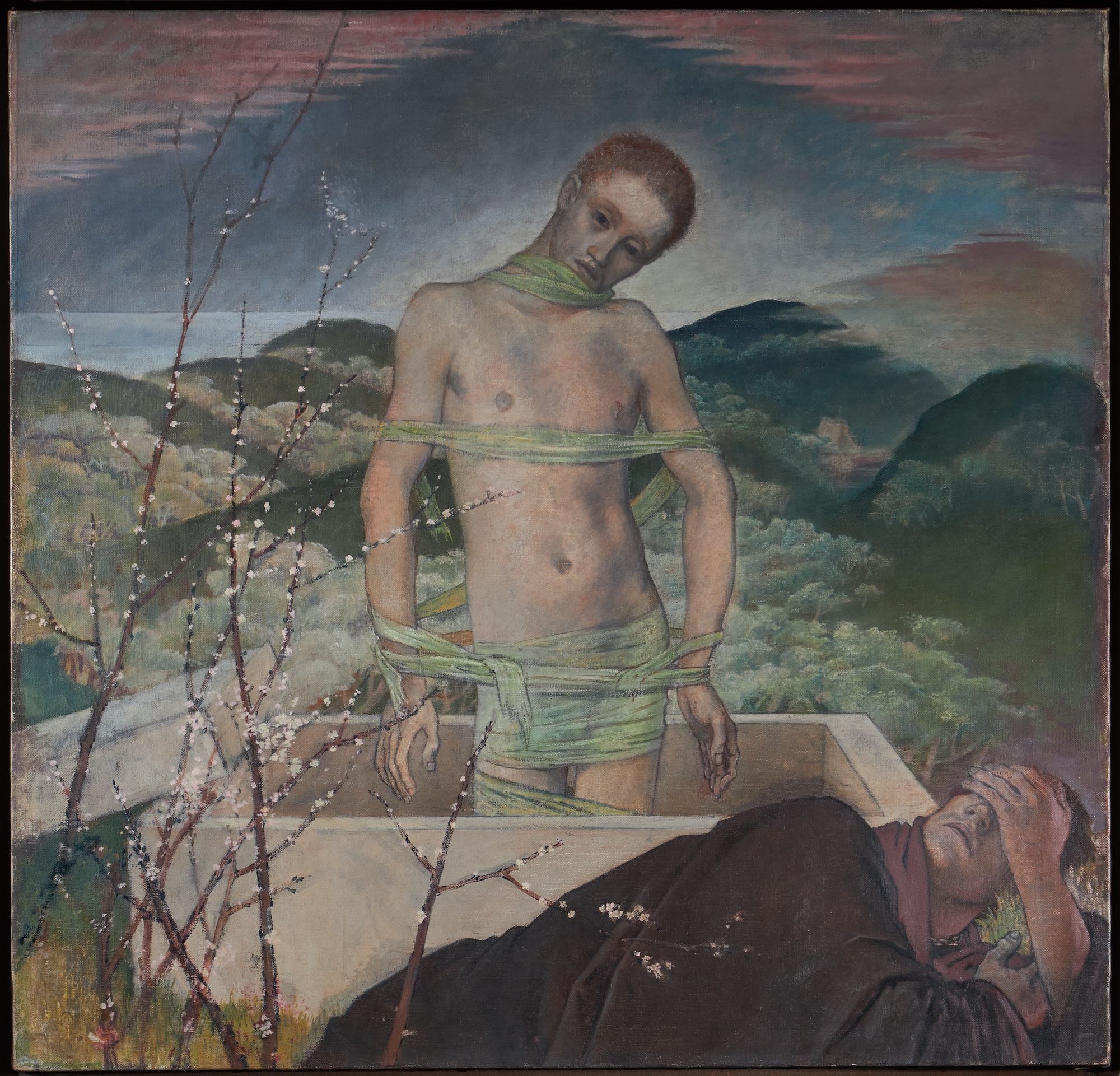

More direct religious interpretations include a vision of the Resurrection titled Resurgam (1929), which depicts Christ as a nubile waif wrapped in tantalisingly diaphanous cloth. Similarly, an image of Saint Sebastian (long considered a gay icon) is presented in dreamy pastel shades. The body is cropped just above the crotch, in a manner that would make even contemporary audiences blush. These examples show that Philpot was not afraid of fusing his Catholic faith with sexually potent imagery, but always stopped short of being explicit.

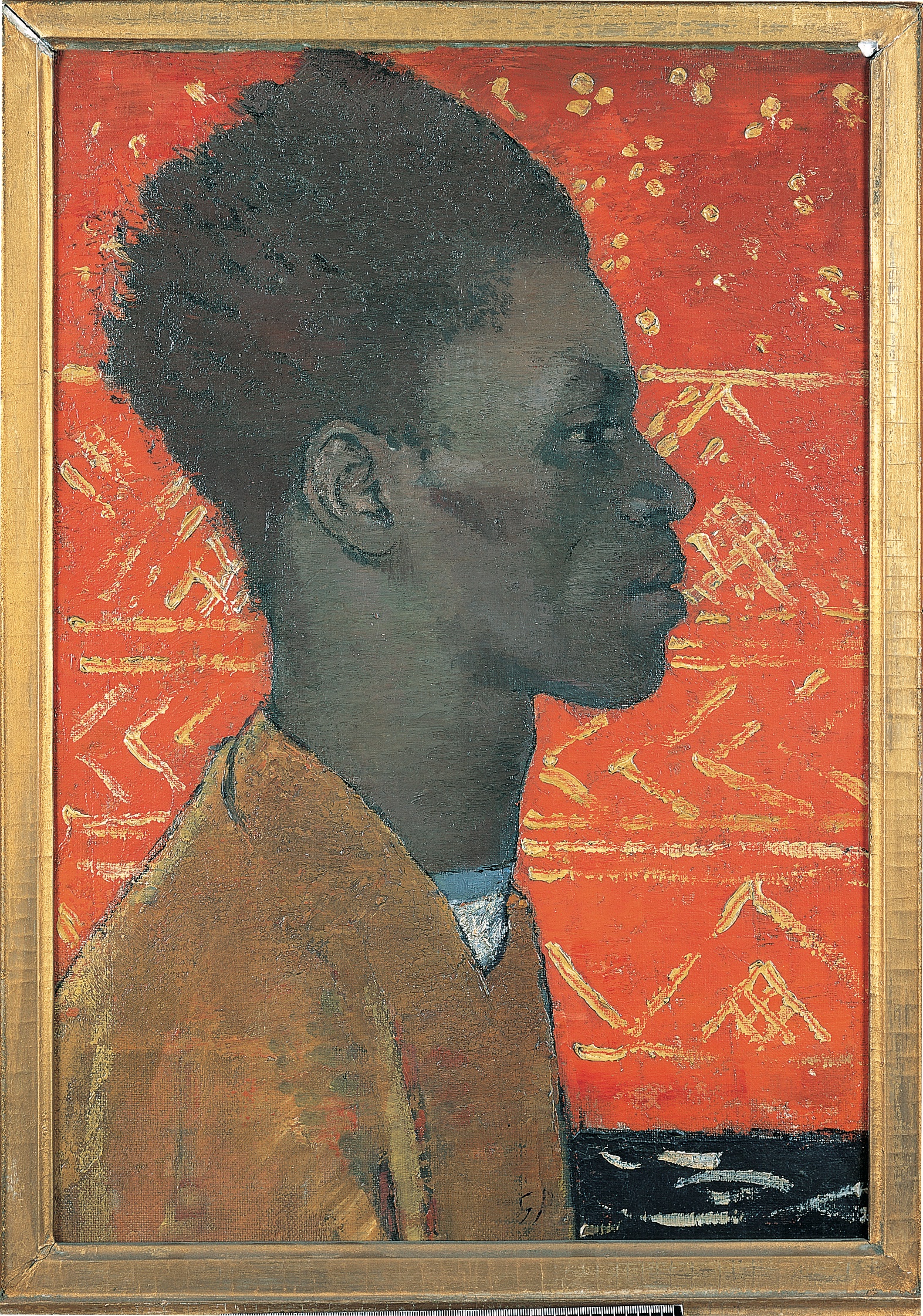

Portrait of Henry Thomas in Profile, 1934-5

Such nuance is also visible in L’Apres-midi Tunisien (1922). This presentation of two Tunisian men is an obvious example of Orientalism, the problematic aesthetic fetishism that dominated in the late 19th century. However, rather that replicating the motif of the odalisque, Philpot presents an intimate scene filled with homoerotic symbolism. The pair’s bodies barely touch, but their gaze is unwavering, and the addition of a white carnation crystallises the idea of pure love. Rather than being simply figures of fantasy, both men appear as individuals, as protagonists in their own romance.

“Philpot was not afraid of fusing his Catholic faith with sexually potent imagery, but always stopped short of being explicit”

Conveying dignity is something that Philpot took seriously in his portraiture, each one imbued with a realism that he cast aside in his more allegorical works. This is evident in several portraits of Black sitters, not least his stunning image of actor and activist Paul Robeson as Othello. This last was given an erroneous anonymous title for decades, despite its clear connection to the actor’s role in the Shakespeare play at the Savoy in London in 1930, which was considered a milestone of representation in British theatre.

Other images were similarly mis-attributed, including several of his servant Henry Thomas, whose long-standing relationship with the artist is complex and somewhat opaque. Though deep affection beyond their working association was evident, the power dynamic was undoubtedly one-sided. Nevertheless, these powerful portraits, including Balthazar (1929) show a dedication to presenting Thomas as a formidable figure, at a time when Black people were rarely protagonists within British paintings, appearing instead as attendants, supporting figures, or merely exoticised symbols.

It is baffling that Philpot’s work is not better known. The answer probably lies in the fact that so few of his paintings are in public collections: his work, especially commissions, were in high demand during his lifetime (he died in 1937) and most still remain in private hands. At a time when digital images are freely disseminated across the world, scant records of many of Philpot’s works even exist online.

Another explanation lies in the fact that he refused to be tied to one style or aesthetic. He flitted between surrealism, hard-edged modernism and rather formal representation, meaning that a singular aesthetic arc is hard to identify. This elusive trajectory has left an artist who was wildly successful during his lifetime all but forgotten. One can but hope that this exhibition is the first step to reappraising a key player in the British Modern canon.

Holly Black is Elephant’s managing editor

Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit is at Pallant House, Chichester until 23 October