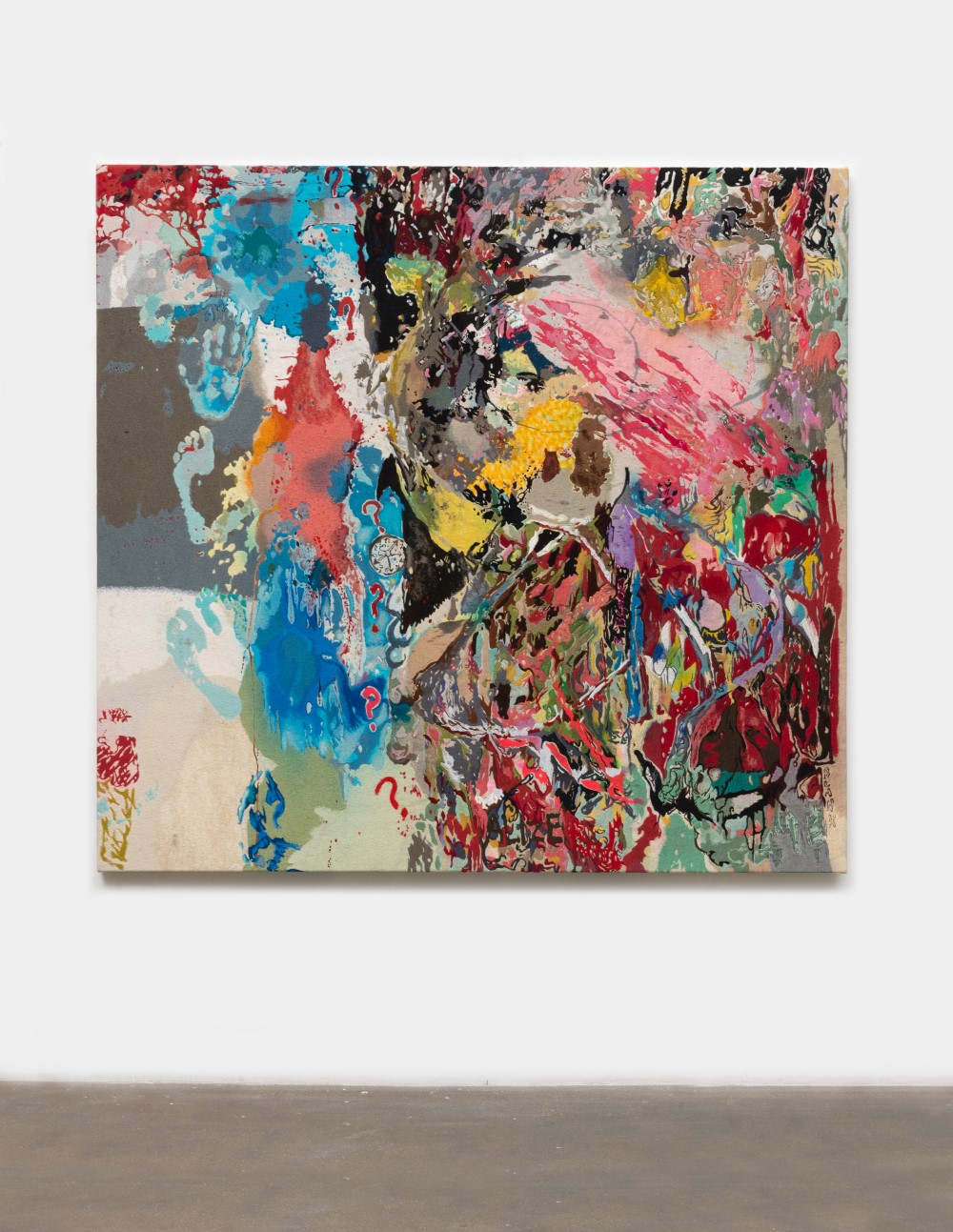

In his new David Kordansky Gallery exhibition, Olvera St., Ivan Morley pays homage to his hometown Los Angeles, where he works from a studio compound located in the city’s historic neighbourhood, Lincoln Heights. Furthering his genre-defying approach to painting, Morley conceived these works in thread on canvas, leather, gold and mother-of-pearl on glass, and paint on butcher paper. His subject matters—which often blend collective histories and folktales—blur the distinction between fiction and reported fact. Coinciding with our times, in which we struggle to separate reality from fiction, Morley’s hallucinatory images and stories both render and distort human remembrance on their surfaces, challenging the evolving processes and objectives of art beneath their gnarly forms and striking hues.

When looking at abstract paintings, audiences tend to spot traces of familiarity, or elements of figuration, that they can latch onto. How do you respond to your viewers’ inclination to seek figurative elements in your paintings?

That tendency is definitely there—I am looking into an area between representation and abstraction, and this in-between area is interesting. I don’t personally tend to see what the audience is seeing, but the baggage is always fun for me to hear about. I’ve spent the last few years reaching a comfort level with non-representation as opposed to being figurative. I stopped making a distinction between my various materials. For example, I work with thread in addition to five or more other techniques, yet I don’t see a hierarchy between fine arts materials and so-called craft materials.

I work past the language of modernist painting. A drip or a gesture used to intimidate me because of its baggage from the 1950s and sixties. I ended up working with oil paint in reverse on glass so that I could abandon the brushstroke and the drip. Everything the Modernists wanted to empty out of the painting, I am taking on now—I find them rich.

Working with needle and thread at your scale implies a degree of patience. Are you patient with your creative process?

I use slightly archaic embroidery machines. The process is not digital the way embroidery is done these days. Sewing is an interesting transition from something associated with comfort and domesticity, but it becomes compulsive and physically uncomfortable after a number of hours. I am more patient about the months a painting takes. Old Masters would take a year or so to finish a painting. There is a rich relationship between the work and the amount of time it takes for its creation. My painting is a literal measurement of a passage of time, which is noticeable because it takes such a different amount of time than something mediated digitally.

Your paintings don’t shy away from direct narratives that charge your work with precise thematic concerns, such as in the True Tale piece. How committed are you to your stories in the creation process?

I shorten the stories down to a sentence or two. The information motivates my activity of sewing. I am still not completely sure about how to include the narrative, especially stories which transform and change with the person telling them. I’m not too invested in how the narrative is received. Retelling of information adds new layers. A True Tale stemmed from a story I read about a former slave in Los Angeles who made a fortune in the nineteenth century after realizing San Francisco was overrun by rats and LA had too many cats. He shipped cats to San Francisco and amassed his wealth, which he later lost in gambling. After some of the cats died along the way, he sued the shipping company and made some profit. When I read this around 2000, I couldn’t stop thinking about the cats drowning. I imagined the story through its periphery; I never rendered the man, but the ship instead. The sails of the ship became a grid of colours I started to use decoratively. I am interested in combining cues from different periods to complicate the colours’ relationship with time.

There is always a pattern and consistency particular to embroidery; however, your style challenges the visual order with fluctuating colours and forms. Is this an intentional stance against the embroidery tradition?

I find a back and forth in my paintings in terms of what is underneath the thread and the surface. I embed thread into ink or watercolour figures that I initially illustrate on the canvas, which is between following a pattern and improvising on the sewing machine. I start working from the lower corner all the way up. I am not able to see the overall composition until the very end. The back and forth between the ink and thread leads to the visual of a finished painting.

You could say California is an influential figure in your work. How is the West Coast reflected in your new exhibition?

The exhibition is specifically regionalist. In the past, I enjoyed the complications of making very Southern California-themed exhibitions in different destinations, such as Germany or Greece. In this case, I am using a very specific location, Olvera Street, which lends its name to the exhibition. In the same story about the entrepreneur who brought the cats to San Francisco, there is a party in which Spanish ranchers specifically served beef and peppers. I like the idea of looking at history through fragrances and flavors. This is also the street where the Mexican muralist Siqueiros did a mural which was quickly painted over in the thirties due to its politically controversial content. Jackson Pollock and Philip Guston were high school buddies in Los Angeles, and they went to see the mural before it disappeared.

Your work zooms us into a pool of memory. It seems to replicate the process where memories blend and bleed into one another; each colour represents an emotion or past moment. In one work, I can see a tiny depiction of a car next to a large smear of paint, for example. Could you talk about this non-hierarchical approach to memories and forms?

I am very interested in how people describe shapes of memories. My fear is that my work will look nostalgic or retro, so I really hope for the present tense. My source material is still memories, but my relationship to history is an alternative one, which is still about the present in a poetic way rather than retrospective. I’d be happy to hear that my paintings reflect experiences of the past. Although I’ve jumped into abstraction more than ever, I can’t fully justify excluding figuration. I like hearing your comment about pools of memory, because after working on this body of work for a year, I don’t have objectivity at the moment. I won’t be able to look at the work separately from my studio for a long time.