Jack Sutherland paints self-portraits, but you’d be forgiven for not recognising him at first, or even second, glance. In one portrait, a nude male back is exposed from behind, with fat bulging around the thick buttocks. Sutherland was inspired by his own experience of sitting on the edge of the bed and feeling his own body, fat deposits and all, move with him. The painting conveys a heightened sense of awareness, and reflects the interiority of the mind as it connects and disconnects from the body. Nude skin is angrily, exaggeratedly pink in Sutherland’s work—an acknowledgement of his own status as a white male painter.

A recent graduate from the Slade’s MFA, he has taken up residence with the Elephant Lab, which offers studio space and all the artist materials that one could wish for. Selected in partnership with New Contemporaries, he tackles subjects as diverse as Brexit, car interiors and Greek tragedy.

What have you been working on during your residency at the Elephant Lab?

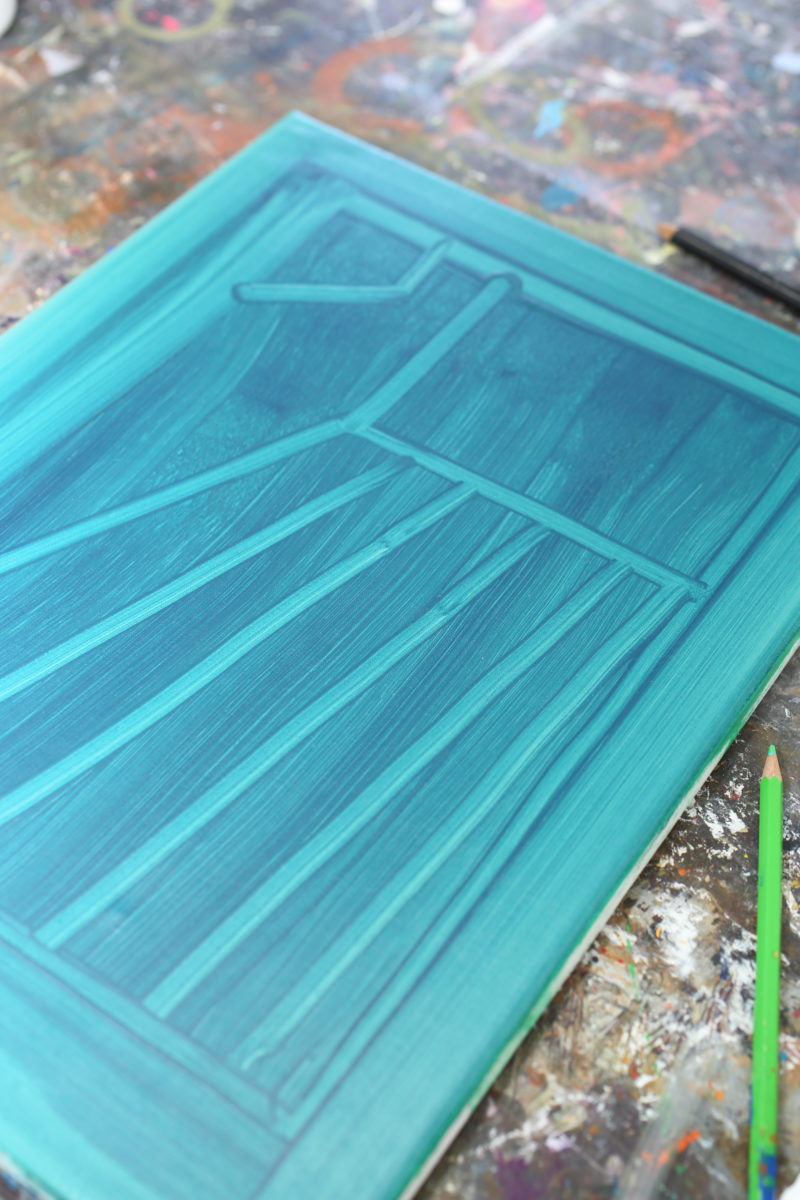

It’s been really nice to have the space to work on multiple pieces at the same time, all slightly larger than those I would normally work on. The studio space I usually have isn’t massive, so I can only really work on one thing at a time. I’ve mostly been working with acrylics here, so drying time isn’t as big an issue as it would be with oils, but having the opportunity to work on lots of ideas at once has been great. I think I can sometimes get hung up on a painting and get stuck, so it’s really nice to be able to just spin around and work on something completely different.

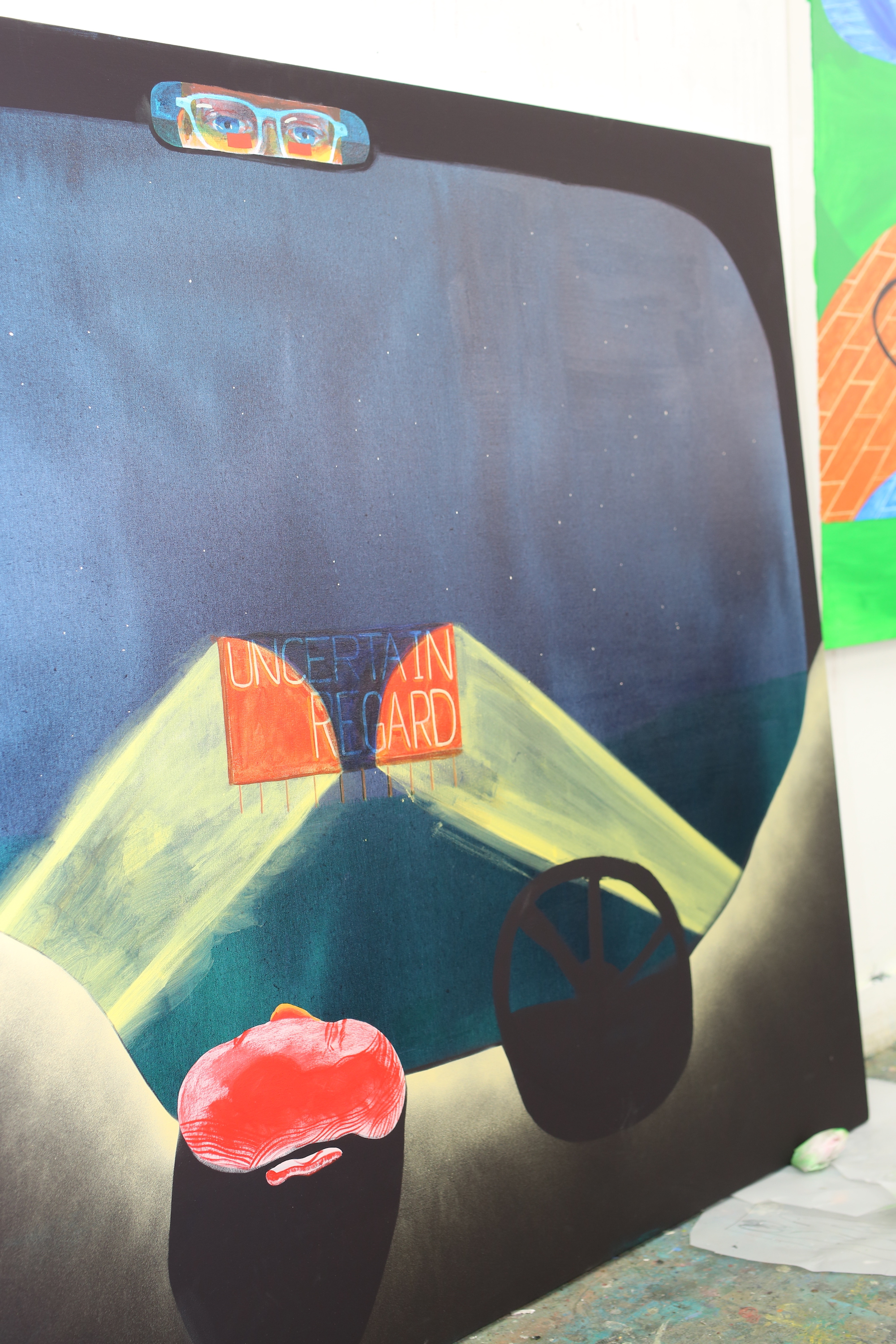

The car is a motif in some of these works. What were you looking to convey with this?

I’ve been working on a series of drawings that all revolve around cars and the car interior: internal and external spaces, and internal thoughts and external voicings—it’s a nice playground of duality. This also relates to my exploration of the masks that people wear; looking at what the mask is covering, and the version of ourselves that we present to other people.

What is the story behind your painting of the back and torso?

While the car images are a bit dreamlike and cerebral—a bit murkier with fewer obvious things going on—the image of the back and torso was just drawn from a very personal experience of sitting on the edge of a bed and becoming very aware of the fat deposits in my back. The relationship you have with your body is really weird, the whole sensory experience you have uses about ten per cent of your body with your sight and sound—you often forget how much landscape there is going on underneath your head.

I wanted to make a painting about that. The initial drawing I did for this just had the yellow and blue colours representing these regions of fat, but then I felt that they functioned portals or ways into the body. I didn’t really want that kind of depth, I wanted it to be this solid form. So that’s where these masks, the Greek comedy and tragedy masks come in. The mask is this idea of the self or the self-portrait.

“I always found Surrealism a bit kitsch or cheesy, but now I feel more comfortable using it”

These overt symbols connect your work, in some aspects, to Surrealism. Is this a conscious point of reference?

With Surrealism in general, and Dali in particular, there’s such a visual abundance of it in popular culture that you just switch off to it after a while. So, I’d switched off to Surrealism in that way and was a bit wary of symbolism—I found it a bit kitsch or cheesy. But as I’ve progressed and have thought more about it, I feel a bit more comfortable using it. I think I’m right on the cusp of investigating this kind of Surrealism at the moment, and it’s interesting doing it 100 years after the fact.

There’s also a lineage that you follow simply by engaging with the world as a painter. How do you feel about working as a painter in the digital age?

Yeah, and being aware of that heritage of painting is something that I really latched onto when I was doing my Master’s last year. If you’re making that kind of work then there is that lineage going back. And in just the action of putting paint on canvas, the history and the weight of it is really intense.

How did you become a painter?

I’ve always been interested in art, and I’ve drawn for as long as I can remember. Drawing’s really important to me, and in some ways, painting felt for me like the next step after drawing. I should emphasise that I don’t necessarily believe that to be universal—drawing can be as important as painting and, in a lot of ways, painting is just the same thing as drawing.

You have a lot of photographs in the studio of your works in progress. Can you tell me a bit about how this aids your process?

I take photos of stuff at the end of the day so I can take it away and look at it on the days I’m not able to come in. It helps me to process the painting, so that when I come back in I know where I want to go with it next. You can see from the photos of their progress that some of the paintings change quite a lot. Sometimes they just don’t sit right in my mind, and I like to change them completely. When working with a triptych it can be really fun to change the three panels and just switch them around. It’s like turning a painting upside-down and seeing if it still works in the same way. Or it’s like The Exquisite Corpse game, where you fold the paper and each draw sections of the body and see how it comes out, which can end up very surreal.

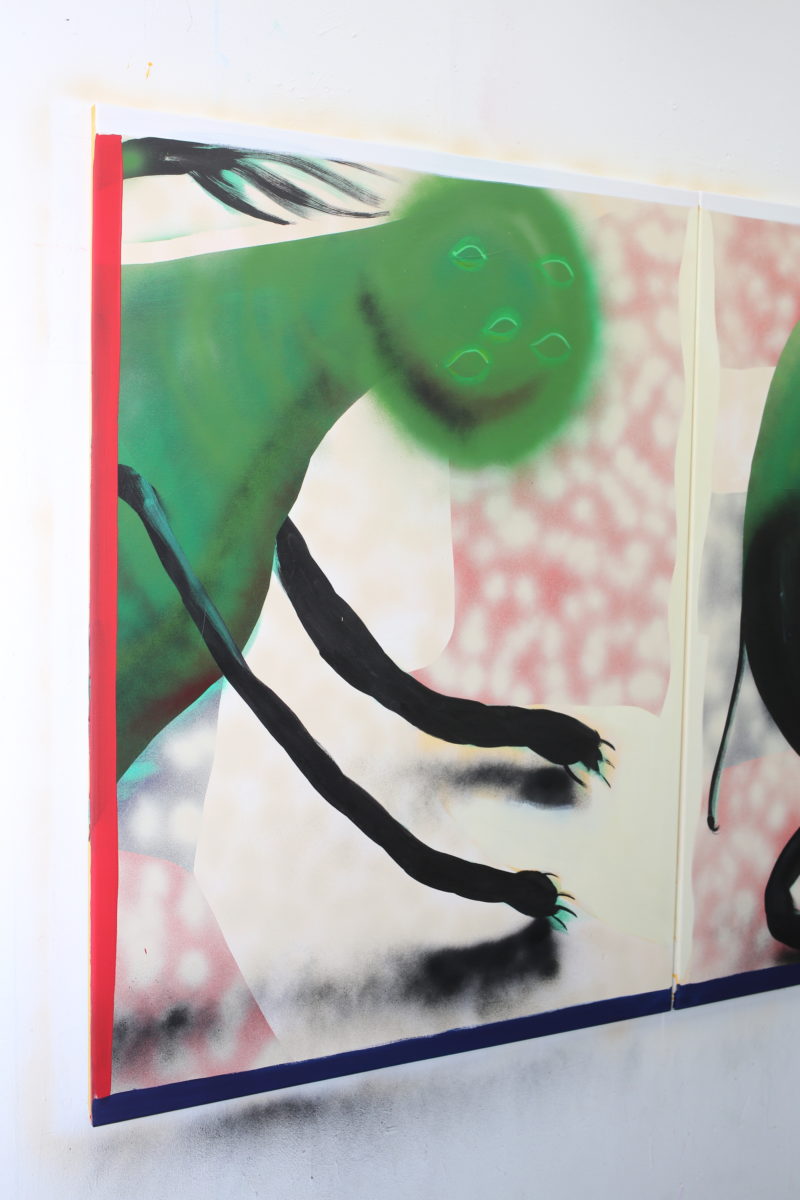

Why did you choose to make a painting of a green monster?

I was thinking about the flags in the painting, and about ideas of nationalism and the views of some people in the UK right now, what with Brexit and everything else around it. I was wondering about the way that many of these people think of non-British people as the “other,” maybe to the point of thinking that “other people are the devil.” I didn’t want to make this completely explicit, because it’s all such a minefield, and I just don’t really have that in me at the moment to explore this explicitly.

So the monster thing isn’t a straightforward metaphor, I thought it would be fun to do a big kind of dragon devil thing. I like how pathetic its little wings are; it’s just kind of a sad figure. If you move from the end panels to the beginning, you get this really nice cyclical effect going on. I also quite love the fact that the cycle basically means that it’s looking at its own arse, and kind of chasing itself. It just seems that that’s something this creature would be doing.

“White masculinity is under rightful scrutiny at the moment, and I believe that this is an important and interesting subject”

And where do you derive some of the colours in your work—for example, the very distinctive green and the vibrant shade of orange. What guides that aesthetic?

I really like the power of colour, and how immediate it can be. I guess in the monster painting the green is kind of related to St George and the dragon as well; it’s very traditional as a representation of that particular beast. With the colours in the painting of the body, with the torso and back, you’ve got tones of Caucasian shame and blushing elements. I’m really interested in that, because I have an interesting relationship with shame. I think I’m kind of an awkward person, and over-process things a lot, so I have this constant narrative in my head of permanent analysis. And I know that a lot of people have that narrative. But it’s nice to be able to represent that human feeling through colour in the blushing tones.

So could we see these paintings as semi-self portraits or vignettes of your state of mind?

Yeah, and I think that element of self-portraiture brings in, by extension, some specifics of the idea of shame that we were talking about—ideas of masculinity and white masculinity. And then being a white male painter as well, which has its own history. I went to an all-boys school, and I was raised by a single parent dad, so I’ve had this really strong male influence throughout my life, and I’m not entirely comfortable with a lot of elements to do with masculinity. White masculinity is under rightful scrutiny at the moment, and I believe that this is an important and interesting subject.

All photographs by Louise Benson

Residencies at Elephant Lab

Practising artists are invited to make proposals for a one month residency at Elephant Lab

APPLY NOW