Under the Influence invites artists to discuss a work that has had a profound impact on their practice. In this edition painter, sculptor and graphic artist Jacqueline de Jong reflects on the way that her Upstairs-Downstairs series was influenced by Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus Stairway

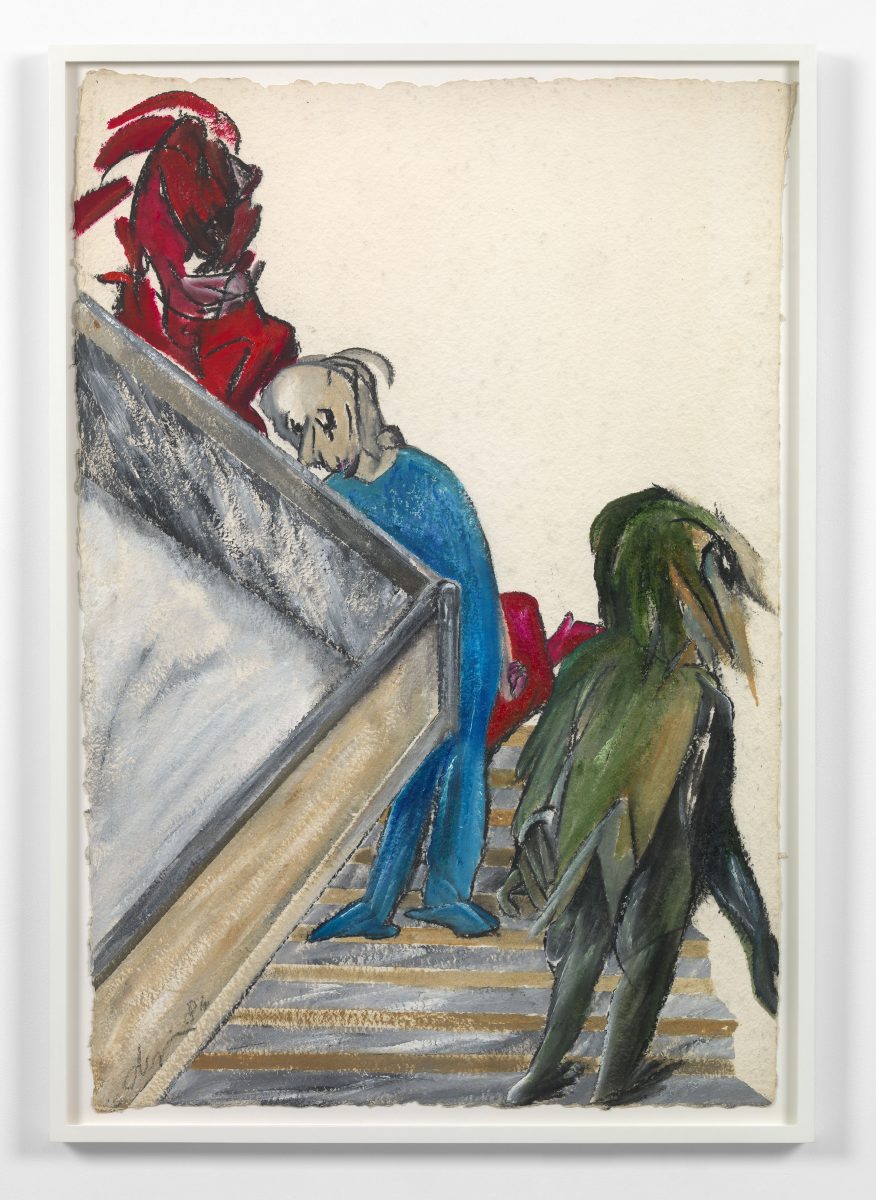

There are lots of things I like very much about Oskar Schlemmer, and the German Expressionists generally. For my original Upstairs-Downstairs series (1984-88), his painting Bauhaus Stairway triggered me very much, because the person in the painting is going upwards, but looks backwards. That’s quite an unusual way of walking up stairs.

When I saw it again, a month ago in MoMA, New York, I thought it was very funny. And it’s not only Schlemmer. There are also many other artists who use this motif: Marcel Duchamp used it in Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, for example.

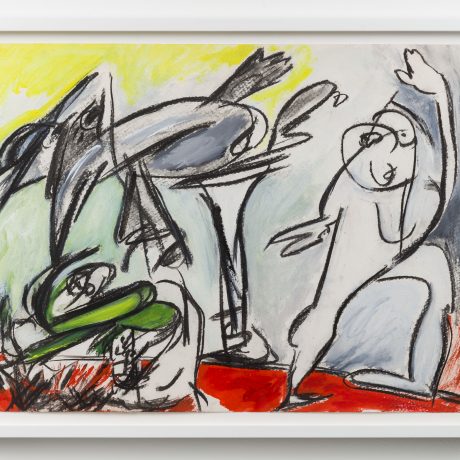

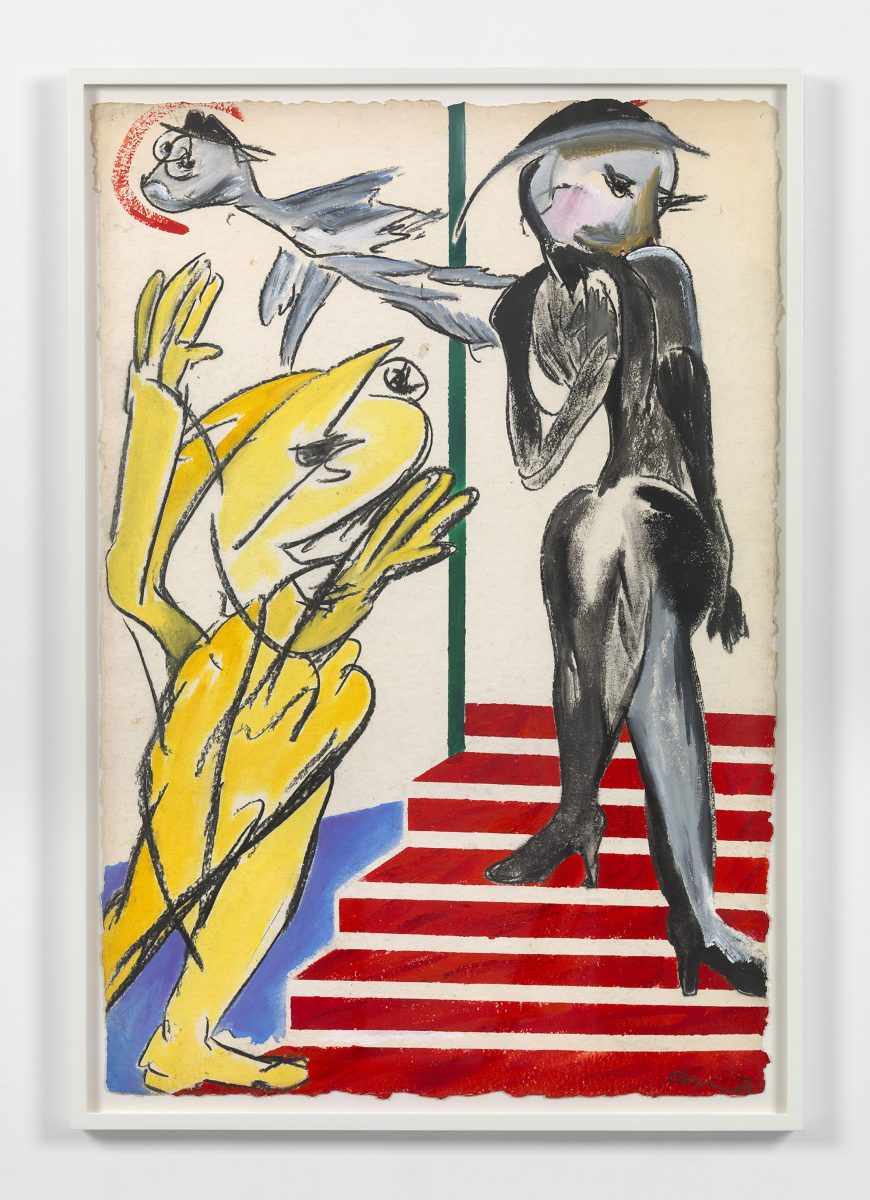

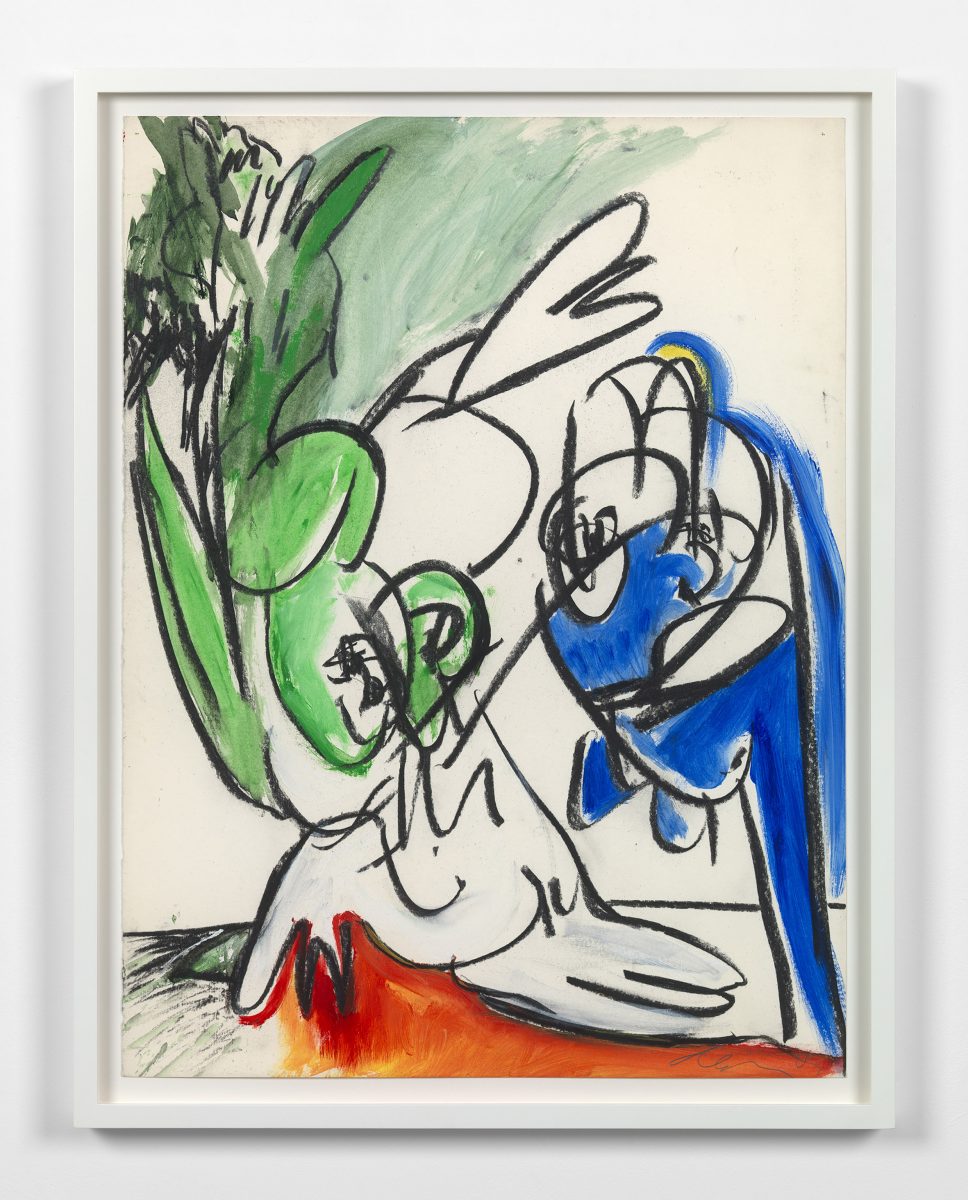

In my series, the stairs are doing a similar thing: going both up and down. But the construction and colour of Bauhaus Stairway also influenced me very much, too, something which extends to all the Expressionists of that period.

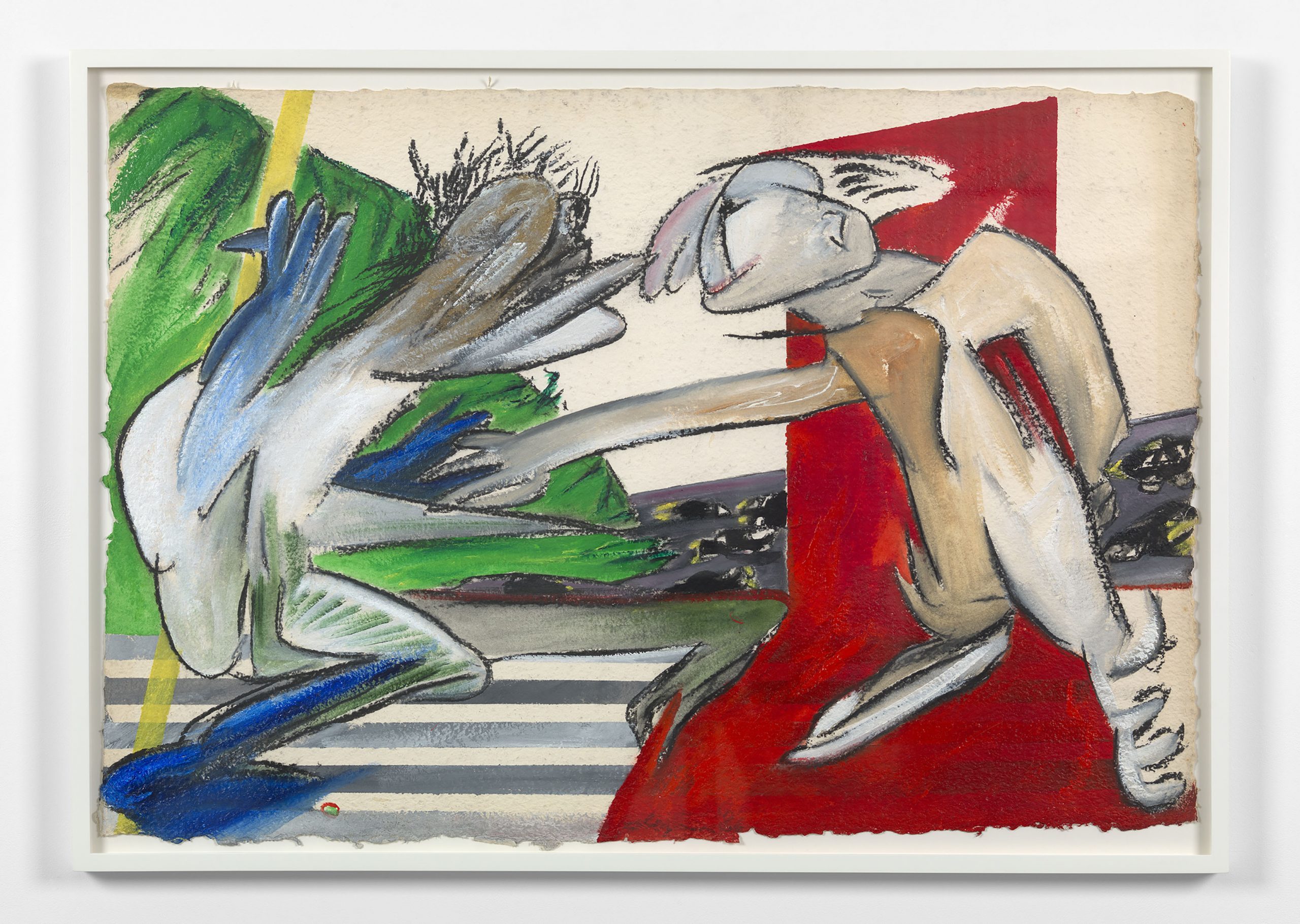

There’s also the influence of Francis Bacon in the construction of my Upstairs-Downstairs paintings, although you can’t see it as much in these newly displayed works on paper as in the larger installation, which originally hung in Amsterdam Town Hall. Some of those paintings are very figurative, very Bacon-like, mostly the portrait-oriented pieces. There are shades of Dada and Surrealism in there, too.

Contrasting the uniformity of the stairs with the moving bodies of the figures was intentional. When I look at the images, I use the vertical and the horizontal very differently in these works to the paintings. On paper, I create a distinct difference between vertical and horizontal. In paintings, most are horizontal, again determined by the building.

“The person in the painting is going upwards, but looks backwards. That’s quite an unusual way of walking up stairs”

The drawings were not in my original show. When I had the show at Amsterdam’s Gallery Brinkman in the 1980s, it was just before the paintings were installed at Amsterdam Town Hall, for which they were originally commissioned.

The commission was to cover the walls of the elevators and the staircases. My first intention had been to create more paintings, but five years ago parts of the building were demolished, so if I had done that now there wouldn’t be anything left. They were then acquired by the Amsterdam Museum.

Schlemmer’s painting depicts the Bauhaus School, and it was very inspiring to hang my painted works in the town hall building, which was constructed by two visionary architects, although they’re slightly different from the Bauhaus style: mainly Cees Dam, who I know very well and who has collected some of my works. Although the building had little to do with Bauhaus, I thought the idea of elevator and staircase could have been something used by the Bauhaus. It’s an interesting dialogue between the works.

“On paper, I create a distinct difference between vertical and horizontal. In paintings, most are horizontal”

The drawings aren’t templates for the paintings. They’re very free and direct on the paper, though they are acrylics, not pencil. There is much less construction in most of them than the painted works, and they are, in a way, made for fun rather than display use.

I had them in drawers, and Juliette Desorgues, curator of visual arts as Mostyn, Wales [where de Jong’s solo show, The Ultimate Kiss, concluded earlier in February], when she came to make her selections, saw all these drawings and said, “We should do something with these.” That’s how this show came into being.

Here on my desk in France I have two books: one I just grabbed that has Bacon’s In memory of George Dyer (1976) on the cover, and another is the catalogue from RB Kitaj’s 2013 Obsessions show at the Jewish Museum in London. Both are significant influences on me. I don’t like to make interpretations or explanations of my work, but curators do.

As told to Ravi Ghosh, Elephant’s editorial assistant

Jacqueline de Jong, Upstairs-Downstairs 1984-1988: The Works on Paper

Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, until 12 March

VISIT WEBSITE