Your graduate show at Goldsmiths dealt with the angst of motherhood. Do you think this is something that is whipped up by our culture, or quite a natural feeling?

A lot has been written about maternal ambivalence or the way that mothers (and other primary caregivers) struggle with the contradictory feelings that they have towards the infants in their care. Childhood psychologists would say this is a natural and necessary part of “good enough mothering”, but it is the source of great angst for most of us, I think. A relationship with a developing child is one that is in continual flux, always altering and shifting. For most parents, the emotional bond with a child is one of the most intense attachments in life, but woven in with the joy is a constant premonition of the loss that will come.

I also think that, especially in our society, the position of mother is economically, socially and politically contradictory at the deepest level. For a very long time now we have lived in a paradoxical situation where the work of social reproduction and caring for children (and adults), although essential for the continuation of life itself, is not valued at all.

You told me before that humour plays a big role in the work. How do you think humour and angst play off against one another?

Humour can be a really effective way to present difficult things like angst, so that we can actually bear to look at them. But it can also be a very good coercion strategy that helps to mask the cracks! I was thinking about how this is played out in popular representations of mothers in film and TV. I love the figure of Elastigirl from The Incredibles, for example.

The joke that elasticity is the one superpower that I could really use as a mother is not lost on me. But after a while it feels as if we are complicit in some kind hypersexualized, neo-liberal reworking of the perfect housewife. No one asks why we should be the ones who have to do all the stretching in the first place. So, it is great to see a trend towards representations of mothers that disrupt the maternal ideal and shed light on the frustration and anxiety we really feel. An example would be Sharon Horgan’s depictions of motherhood in Catastrophe and Motherland.

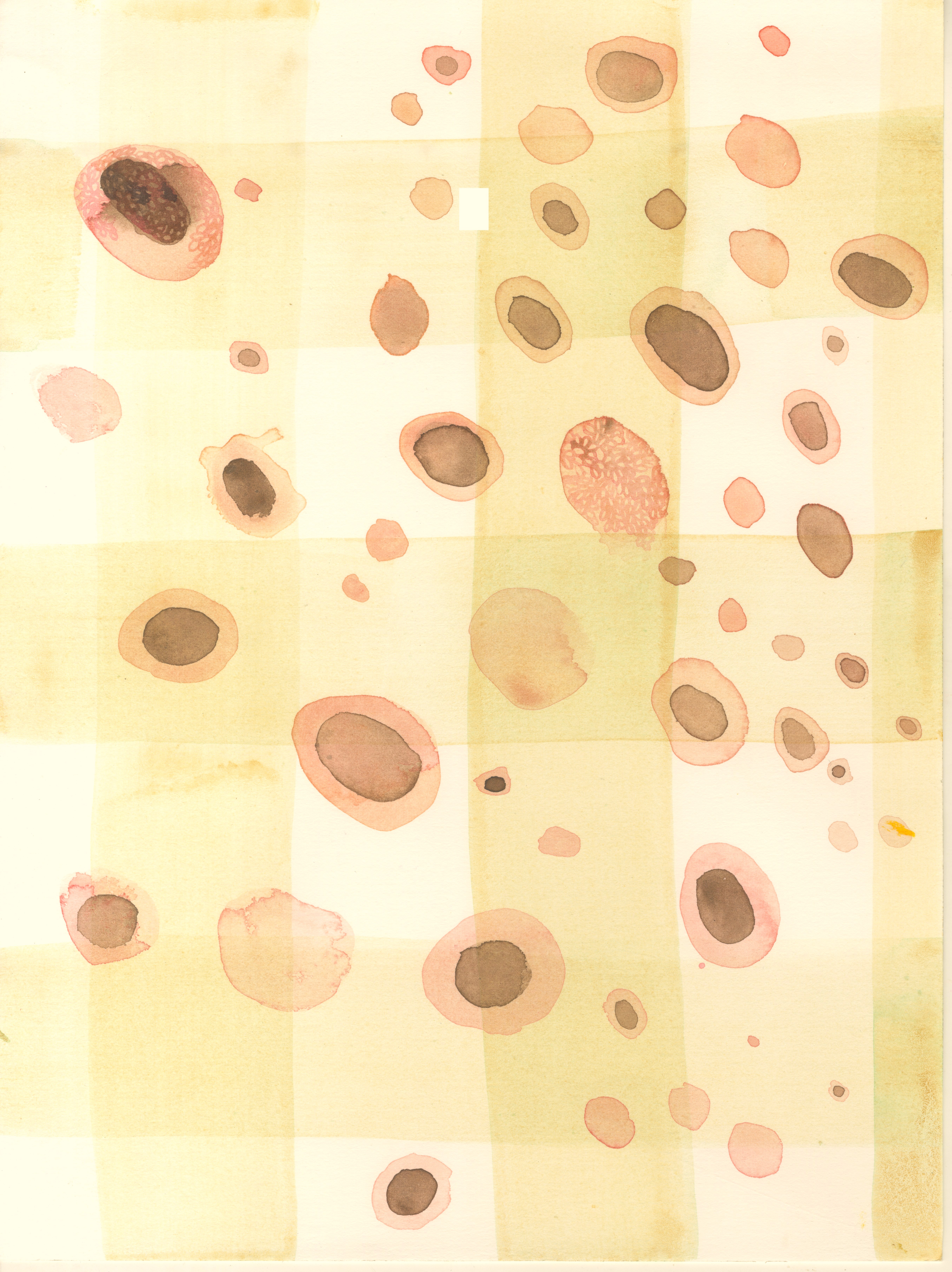

Your more recent work looked at angst surrounding the body—illness, tumors and spreading biological forms—contrasted against the clean forms of the hospital…

My interest in sick bodies and microbiology has been there for a while. Mostly, again, in relation to being a mother and the anxiety we feel about trying to keep our children healthy and caring for them when they are sick. On another level, I have been increasingly interested in the idea of the non-human—the way that we are in fact not one living thing, but a whole host of organisms that are proliferating and growing away. Part of our anxiety comes from trying to maintain a sense that we are separate entities in control of nature. We continually try to achieve some kind of sanitized, germ-free zone around ourselves.

Another very significant influence has, of course, been my experience of cancer. I recently finished a year of cancer treatment and I think I was very much making sense of the trauma of that process during the residency. The contrast between the unyielding hardness of the hospital surfaces and the raw vulnerability of skin and bodily functions seemed to sum up something of how it feels to be in the treatment machine.

“It seems crucial that we talk about the reality of cancer, especially since it’s such a common experience”

The experience of motherhood and battling cancer is quite clouded in our culture; we don’t tend to share all the details. Do you think, in suppressing openness around this, we allow for angst to build up?

I don’t think that suppressing or holding things in ever relieves worry or anxiety. In the absence of another voice I think it’s our tendency to create our own fantasy (or nightmare) scenario and distort reality. In the case of cancer there is very good evidence to suggest that stress is a causal factor and then the process of diagnosis and treatment is hugely stressful. So, it seems crucial that we talk about the reality of cancer, especially since it’s such a common experience and because there are still so many myths and misunderstandings surrounding the condition.

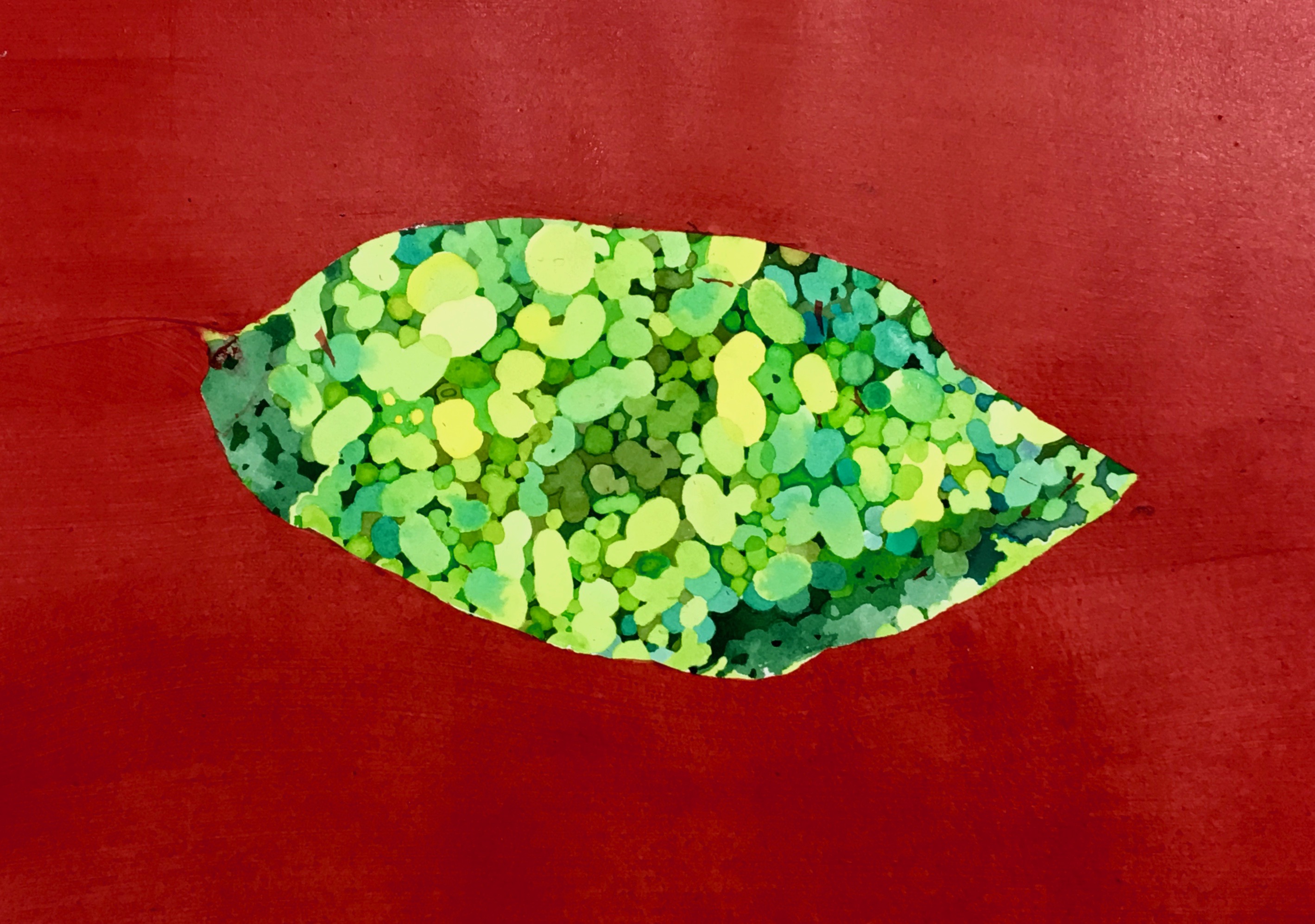

Metastatis, 2016

Your use of scale feels cinematic in some ways—it can be difficult to tell if you’re looking at something really big, or small in close-up. How do you feel this emphasizes the mood in your work?

I think the scaling up sometimes has the effect of slowing things down or creating a kind of sense of suspension and stillness—or maybe unreality. I hope that it can sometimes create a sense of surprise or threat. I’m trying to get to a place where the viewer is not quite sure what they are looking at or is disconcerted in some way, and so my aim (for some of the work at least) is for it to oscillate between the micro and macro and also the abstract and the representational.

In terms of content I also want to shine a light on the teeming life that is going on in plain sight all the time. I find that notion kind of horrific and destabilizing, but I also think it’s a really exciting paradigm shift—this thinking beyond the human.

This feature originally appeared in issue 35

BUY ISSUE 35