Stephanie Wambugu visits Janiva Ellis’s StackedPlot at 47 Canal, New York.

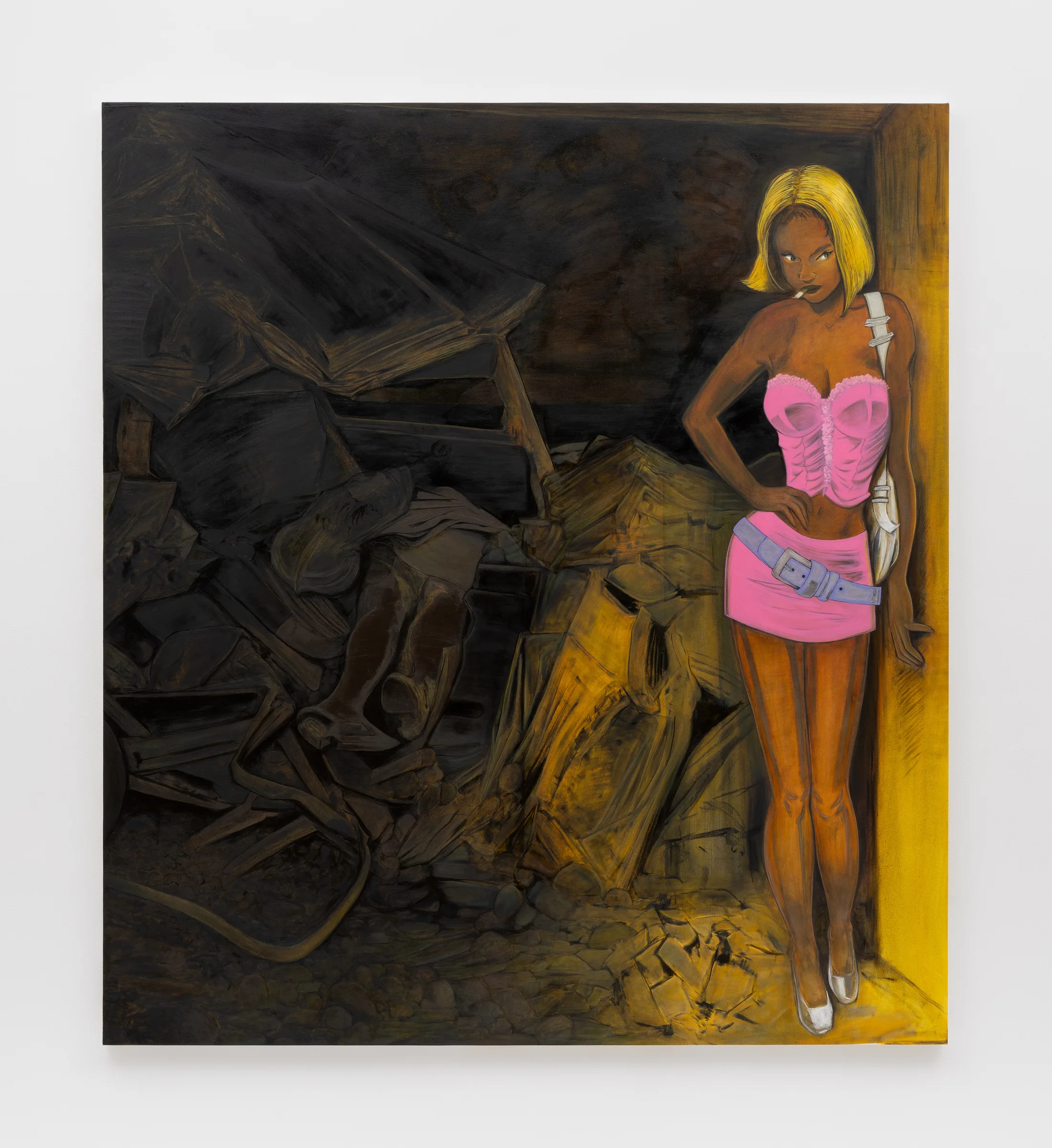

I visited Janiva Ellis’s studio on Canal Street as she completed the paintings that make up StackedPlot, her third solo exhibition that is currently up at 47 Canal. The works in progress already bore Ellis’s distinctive hand and her perspective that manages to problematize and make new our oldest symbols as well as those just springing up from their respective subcultures. But to call the paintings half-finished does not really capture what I saw, as they were already dense and evocative, characteristic of Ellis’s’ ability to construct multi-layered scenes where the tension between concealment and visibility is brought to the fore. These paintings subvert well-trodden themes. They also attend to the burden of representing racialized subjects in a way that evades and confronts viewers, metabolising the traps and tropes of representation within the work itself. Yet nothing feels overwrought and the paintings are never didactic. What they communicate to a viewer, they communicate subtly. Still, the experience of looking at them is one of sustained intensity and force, not only because of their scale – the paintings are large – but because of the feeling that something looms beyond the foreground, that something haunts the surface.

Despite the intensity of these paintings, there is something humorous and glib about Ellis’s figures, which is not to say they are not substantive or are ironic in a way that relies on spectacle and shock alone. In their moments of levity, Ellis’s paintings embody Freud’s idea that what is taboo or suppressed can be cloaked in humour, smuggled into public view by making us laugh. We’re disarmed by what is funny and attracted to it as it suggests a shared context. Humour is referential and requires an inability to preempt what the viewer knows and brings to a text or an encounter. In this way, it is culturally specific. The cyborgish singer standing atop a disco ball in Primitive Prophecy is a funny character – she sports a mischievous look as she holds the cord of a microphone in her clenched teeth. She is also a culturally specific figure, not in terms of discernible racial or gender identities, but in the sense that there is probably no figure more quintessentially American than an out of touch and self-congratulatory talk show host, whose essence this figure captures. Even as a parody of a certain type, she communicates something grim and serious, just as shit posting through our bleak present betrays deep panic and anguish. Ellis’s earlier work used cartoonish figures and appropriated pop cultural images to similar effect. Her exhibition RATS at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami contains many smiling subjects whose grins evoke – rather than happiness – terror and unease. In the paintings from the show at ICA, figures overlap, crash together and fall, in scenarios that feel like sombre refashionings of iconic comics like Looney Tunes or Tintin. What is different in StackedPlot is that the allusions are buried more deeply than they were in RATS. Though there is a continued preoccupation with appropriated images and the associations they carry, they are less readily available in StackedPlot, less immediately legible. To be confounded – to have my expectations usurped and ignored – is what I turn to art for. To encounter what is familiar and widely palatable one turns to TV; paintings do something else. That these paintings process the detritus of pop culture in a way that isn’t laudatory and glorifying, and with sharpness and good humour, makes them feel conversant with our contemporary moment, rather than tediously trapped within it. In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Freud writes that “A favourite definition of joking has long been the ability to find similarity between dissimilar things – that is, hidden similarities,” and I think this is true of Janiva Ellis’s work: it brings together disparate things and assimilates difference seamlessly, compressing long histories and conflicting narratives. The strands which connect everything may not be visible upon first glance, but they are there.

Leitmotifs, like the exclamation points that appear in Athena Vibed and Primitive Prophecy, do not jump out at the viewer immediately. They are faint and are so integrated into their surroundings that at first glance they are indistinguishable from them. In Primitive Prophecy the exclamation point is fashioned out of toppling skyscrapers; one has to stand at a distance to make the punctuation out. Symbols like this are obscured and submerged in a way that keeps parts of the paintings’ idiom elusive, not fully “translatable”. In not giving away these concealed symbols so easily, I felt that these paintings evoked the idea of opacity, which comes from Martnician poet and philosopher Eduoard Glissant’s influential Poetics of Relation. Opacity, or that which is untranslatable across cultures, is something to which Glissant believed all peoples have a rightful claim. In Poetics of Relation, Glissant writes that “If we examine the process of “understanding” people and ideas from the perspective of Western thought, we discover that its basis is this requirement for transparency. In order to understand and thus accept you, I have to measure your solidity with the ideal scale providing me with grounds to make comparisons and, perhaps, judgments. I have to reduce.” For Glissant, it is in reduction and flattening of difference that we make the other comprehensible to ourselves. He sees opacity as a strategy for evading the reductive gaze Glissant attributes to the West. This tension between the opaque and the transparent is especially evident in figurative paintings where a painter’s marks form pictorial representations of people and things, each carrying their myriad cultural associations. When the painter and subjects are Black, as they are in the case of Janiva Ellis’s’ StackedPlot, the associations these symbols carry are even more fraught, more likely to be generalised in a way that overlooks their complexity. The paintings in StackedPlot are incredibly dense, even the most spare works in the show, like Island in the Sun, are intricate and elusive. Any generalised summation of what the painting is about would not be a stand in for seeing the actual painting. There is an impulse to read Black figurative painting as autoethnography even when the paintings deliberately oppose those readings.

The opening for StackedPlot was crowded; it was full of people paying attention. The paintings, in all their detail, show a voracious appetite for the pop cultural and art historical, the speculative and the mundane. These seemingly disparate strands of social life are handled with equal seriousness, positioned alongside one another, exempt from any hierarchy. The old and new appear contemporaneously in these scenes, just as humour comes up against more severe qualities. It is clear looking at these paintings that things like pop music and talk shows can’t be separated from the wars during which they are made. StackedPlotmakes a case for looking and looking again in a way we are often too inundated with photographs, advertisements and sensational stories to do. We look quickly and tune out often, taking in only what we can immediately assimilate. None of the paintings in StackedPlot moralise, but in their irreverence and density, they capture contemporary life, they are as complex as the conditions under which they are made. Without sanctimony, the feeling of bearing witness to the abject while everything conspires to distract came across with an eerie force, like a haunting. It’s hard to look away.

Words by Stephanie Wambugu