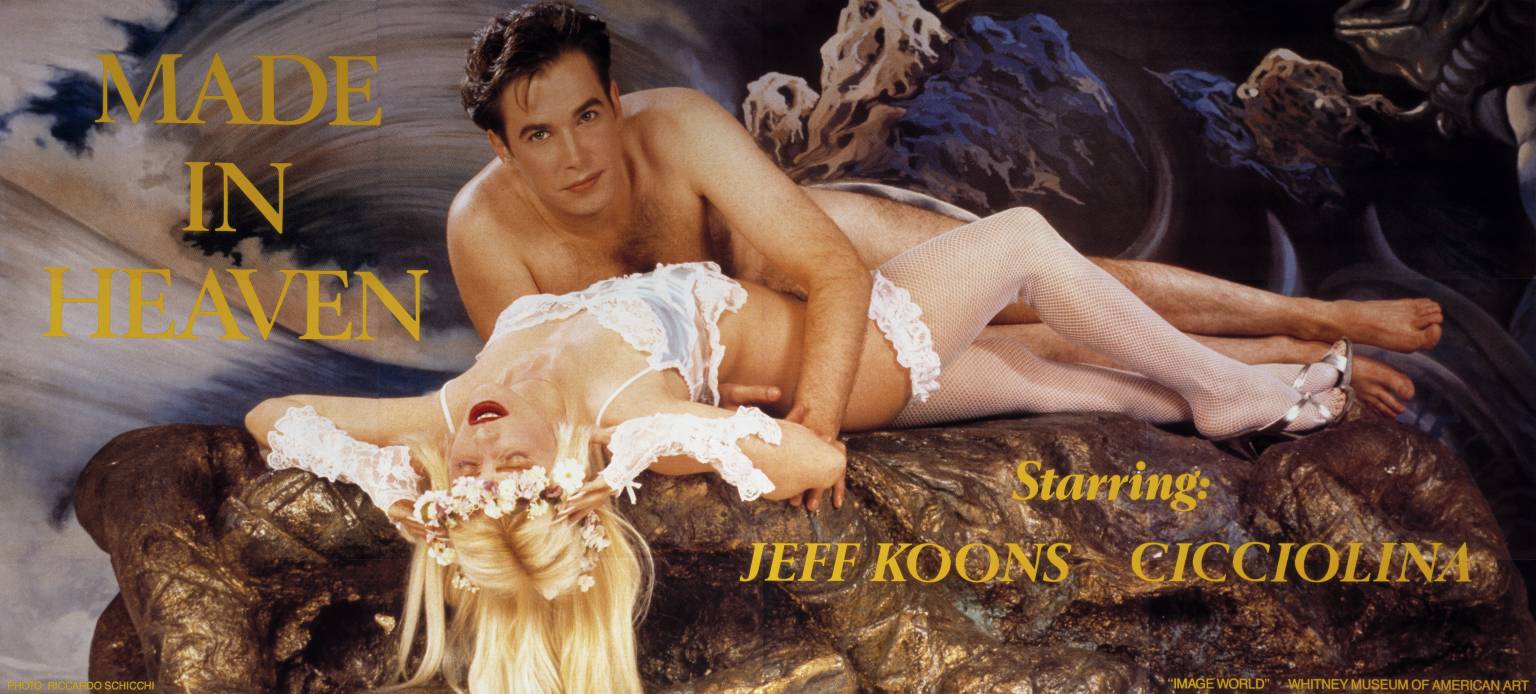

I first encountered Made in Heaven while still a teenager, hungry for anything that tipped the balance of acceptability beyond the staid constraints of life as I knew it. With a juvenile interest in censored art, my eyes lit up when I read that the series of hyperrealistic sculptures and photographs had scandalised the art world upon its premiere at the Venice Biennale in 1990. The age-old art vs porn debate is well-worn, but even the most explicit artworks are unlikely to find quite so much common ground with the booming pornography industry as Jeff Koons’ long-immortalised lovefest.

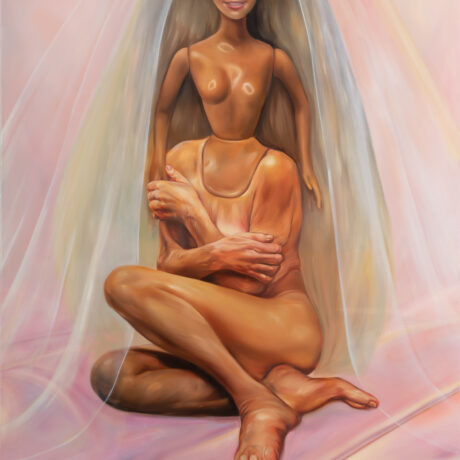

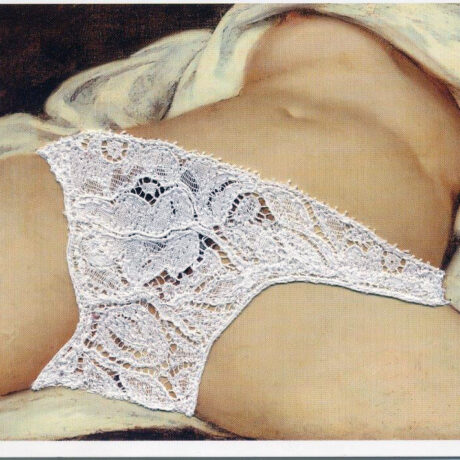

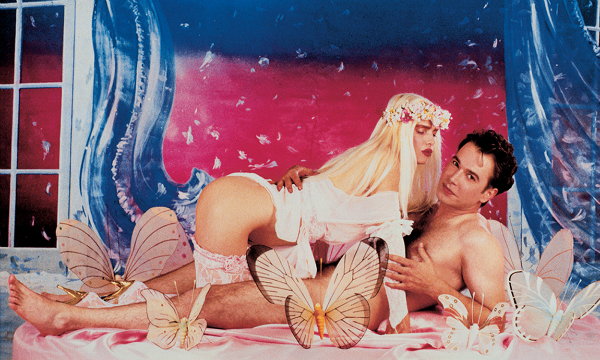

It’s not often that a bonafide porn star makes an appearance in the hallowed museums and galleries of the art world. Ilona Staller, an Italian porn actress also known as La Cicciolina, is shown within the welcoming arms of Koons himself. She appears as a reborn biblical Eve figure, frolicking in the Garden of Eden. Free of shame, she is cast in baby blue stockings and suspenders, a female archetype firmly of her time. In a number of photographs, Koons and Staller entwine before the camera, his hand cradling her thigh, her head thrown back as if in mid-orgasm. With crude titles such as Jeff Eating Ilona, Ilona’s Asshole and, simply, Blowjob, they get right to the point. “Where do people start to feel guilt and shame and rejection of the self?” Koons asked in a 2015 interview, reflecting on the series almost 25 years on. “I wanted to go into Made in Heaven with biology; procreation; looking at nature, and to deal with ideas of the eternal.”

“He conjures the commercialisation of desire and suggests that everything (and everyone) has a price”

The couple’s poses recall paintings of the Baroque and Rococo periods, from Berniniʼs expressions of physical ecstasy to the hazy idyll depicted by Fragonard and Boucher, but the series does more than subvert art history. Koons is an artist best-known for his brash comments on the consumerism of our contemporary age, and in these images he targets the most marketable product of all: sex. The billboard format of the title artwork of the series, measuring almost seven metres wide, only served to emphasise this easy sell. He conjures the commercialisation of desire and suggests that everything (and everyone) has a price.

To look back on the series in 2020 is to recognise the acceleration of this production line of readily available (and highly aestheticised) sex in the age of the internet. Succinct titles, like Dirty – Jeff On Top, are suggestive of the ease with which human desire can be condensed into nothing more than search terms on an X-rated website. Similarly, the escapism of the backdrops and sets, conjuring majestic sunsets and crashing waves, is offset by their distinctive flatness. It is a self-evident illusion that today conjures the equivalent flatness of the digital screen, where Zoom backdrops and face filters render our lives more appealing—more seductive—than they really are. OnlyFans, a digital subscription platform used primarily for pornography, now enables its fast-growing userbase to not only cast themselves as the object of desire, but to monetise it too.

For Koons, however, Made in Heaven was never just about the creation of fantasy. He married Staller in 1990, despite the pair not sharing a common language at the time. The series had bled beyond the stiff boundaries of the artwork and come to life, like Pygmalion and his ivory statue. “It was as though he felt the Made in Heaven work wouldn’t be authentic unless they were married,” Koons’ gallerist Jeffrey Deitch later said. “It was a moral issue for him.” Staller herself was elected to parliament in Italy 1987, founded the Party of Love and ran for local office several times before founding DNA: Democrazia Natura Amore (democracy, nature, love).

“The series had bled beyond the stiff boundaries of the artwork and come to life, like Pygmalion and his ivory statue”

Meanwhile, her career as a porn star has not gone unrecognised. Last week, Pornhub announced that it would give Staller its first-ever lifetime achievement prize, stating she is “the embodiment of an international superstar. Her life and legacy is an intersection of art, fashion, politics and porn.” Although the relationship between Koons and Staller didn’t last (they divorced acrimoniously in 1998), their short-lived union reveals the dangerous allure of the blurred line between fantasy and reality. A bitter custody battle ensued over their son, demonstrating just how far Adam and Eve had to fall from paradise. Made in Heaven represents a heady blend of self-delusion and looming regret; as a modern cautionary tale, it is surprisingly moralising considering its smutty origins. Ultimately, it seems to say, be careful what you wish for.