This feature originally appeared in Issue 27

I’m an unashamed Domino’s obsessive. Are you also?

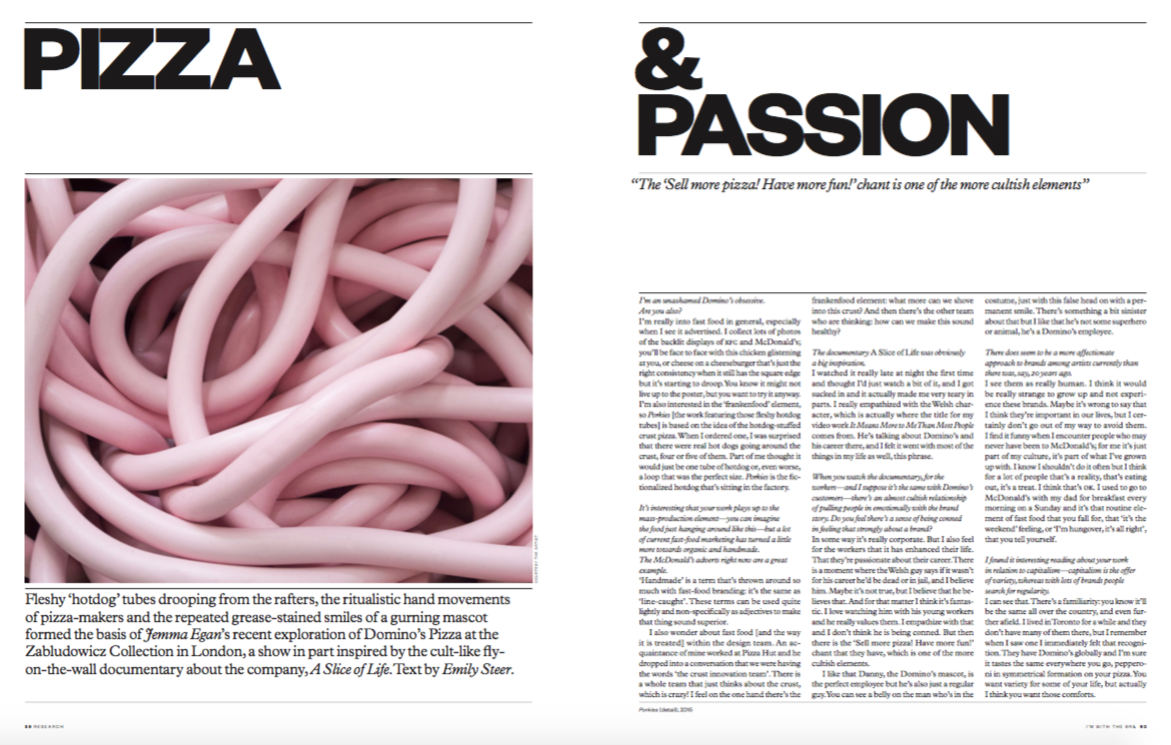

I’m really into fast food in general, especially when I see it advertised. I collect lots of photos of the backlit displays of KFC and McDonald’s; you’ll be face to face with this chicken glistening at you, or cheese on a cheeseburger that’s just the right consistency when it still has the square edge but it’s starting to droop. You know it might not live up to the poster, but you want to try it anyway. I’m also interested in the ‘frankenfood’ element, so Porkies [the work featuring those fleshy hotdog tubes] is based on the idea of the hotdog-stuffed crust pizza. When I ordered one, I was surprised that there were real hot dogs going around the crust, four or five of them. Part of me thought it would just be one tube of hotdog or, even worse, a loop that was the perfect size. Porkies is the fictionalized hotdog that’s sitting in the factory.

It’s interesting that your work plays up to the mass-production element—you can imagine the food just hanging around like this—but a lot of current fast-food marketing has turned a little more towards organic and handmade. The McDonald’s adverts right now are a great example.

‘Handmade’ is a term that’s thrown around so much with fast-food branding: it’s the same as ‘line-caught’. These terms can be used quite lightly and non-specifically as adjectives to make that thing sound superior. I also wonder about fast food [and the way it is treated] within the design team. An acquaintance of mine worked at Pizza Hut and he dropped into a conversation that we were having the words ‘the crust innovation team’. There is a whole team that just thinks about the crust, which is crazy! I feel on the one hand there’s the frankenfood element: what more can we shove into this crust? And then there’s the other team who are thinking: how can we make this sound healthy?

The documentary A Slice of Life was obviously a big inspiration.

I watched it really late at night the first time and thought I’d just watch a bit of it, and I got sucked in and it actually made me very teary in parts. I really empathized with the Welsh character, which is actually where the title for my video work It Means More to Me Than Most People comes from. He’s talking about Domino’s and his career there, and I felt it went with most of the things in my life as well, this phrase.

When you watch the documentary, for the workers—and I suppose it’s the same with Domino’s customers—there’s an almost cultish relationship of pulling people in emotionally with the brand story. Do you feel there’s a sense of being conned in feeling that strongly about a brand?

In some way it’s really corporate. But I also feel for the workers that it has enhanced their life. That they’re passionate about their career. There is a moment where the Welsh guy says if it wasn’t for his career he’d be dead or in jail, and I believe him. Maybe it’s not true, but I believe that he believes that. And for that matter I think it’s fantastic. I love watching him with his young workers and he really values them. I empathize with that and I don’t think he is being conned. But then there is the ‘Sell more pizza! Have more fun!’ chant that they have, which is one of the more cultish elements.

I like that Danny, the Domino’s mascot, is the perfect employee but he’s also just a regular guy. You can see a belly on the man who’s in the costume, just with this false head on with a permanent smile. There’s something a bit sinister about that but I like that he’s not some superhero or animal, he’s a Domino’s employee.

There does seem to be a more affectionate approach to brands among artists currently than there was, say, 20 years ago.

I see them as really human. I think it would be really strange to grow up and not experience these brands. Maybe it’s wrong to say that I think they’re important in our lives, but I certainly don’t go out of my way to avoid them. I find it funny when I encounter people who may never have been to McDonald’s; for me it’s just part of my culture, it’s part of what I’ve grown up with. I know I shouldn’t do it often but I think for a lot of people that’s a reality, that’s eating out, it’s a treat. I think that’s ok. I used to go to McDonald’s with my dad for breakfast every morning on a Sunday and it’s that routine element of fast food that you fall for, that ‘it’s the weekend’ feeling, or ‘I’m hungover, it’s all right’, that you tell yourself.

I found it interesting reading about your work in relation to capitalism—capitalism is the offer of variety, whereas with lots of brands people search for regularity.

I can see that. There’s a familiarity: you know it’ll be the same all over the country, and even further afield. I lived in Toronto for a while and they don’t have many of them there, but I remember when I saw one I immediately felt that recognition. They have Domino’s globally and I’m sure it tastes the same everywhere you go, pepperoni in symmetrical formation on your pizza. You want variety for some of your life, but actually I think you want those comforts.