When I meet Jin Han Lee for the first time, she is wearing a loose black boiler suit splattered with paint, while the studio that she has taken up residence in for the month is almost spotless. That’s not to say she hasn’t been busy—rather, it becomes quickly apparent that her way of working is methodical and deeply considered. Scrawled notes can be spotted on the walls alongside her works-in-progress, specifying the exact type and blend of paint used in each. Stacks of paintings, on paper and on loose linen, can be found by the window, where the last of the daylight is streaming into the room.

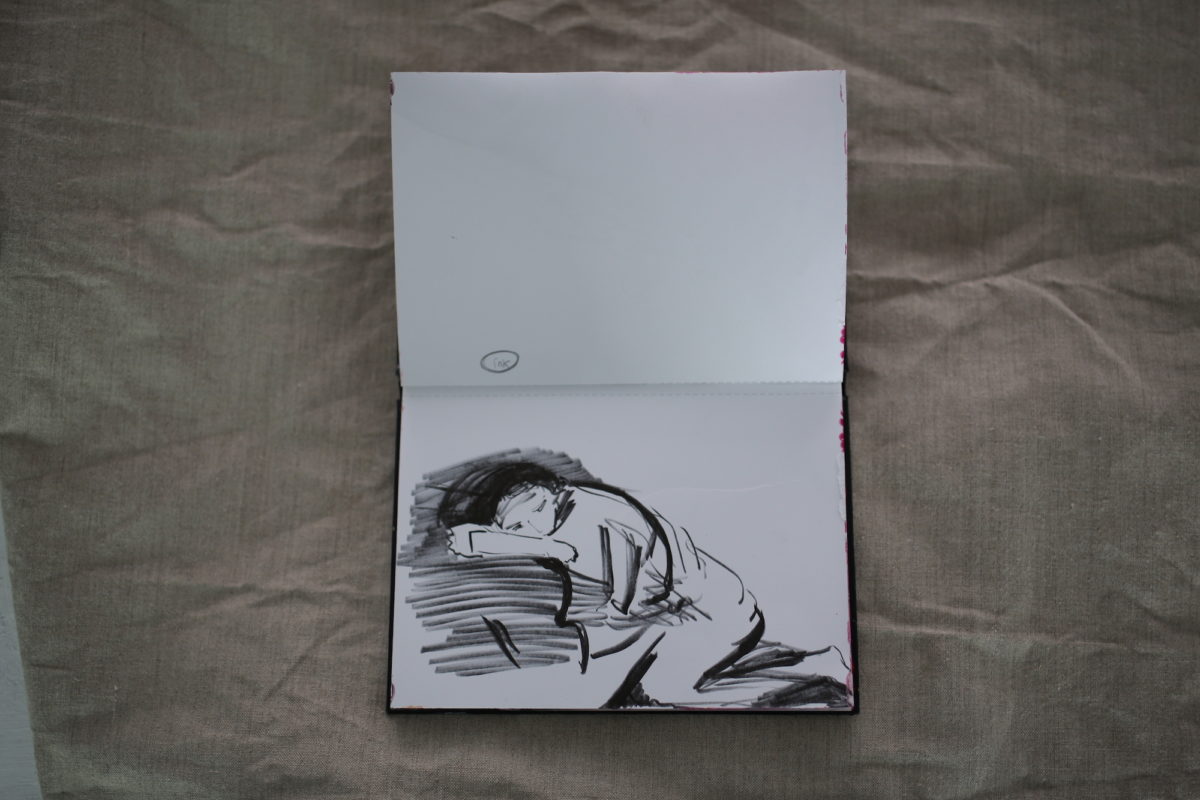

Lee is the first artist-in-residence at Elephant Lab to be selected in partnership with New Contemporaries, the prestigious programme that has continuously supported emergent art practice in the UK since 1949. Lee was selected in 2015 for her instinctive, colourful paintings that draw upon both her South Korean heritage (she grew up in Gangnam in Seoul) and her experience of living and working in the UK, where English is her second language. Her paintings often show women at rest and at play, exploring moments of introspection and connection that are difficult to describe in words. For Lee, painting becomes a language through which she is able to communicate the unspoken emotions of everyday life.

What have you been up to on this residency?

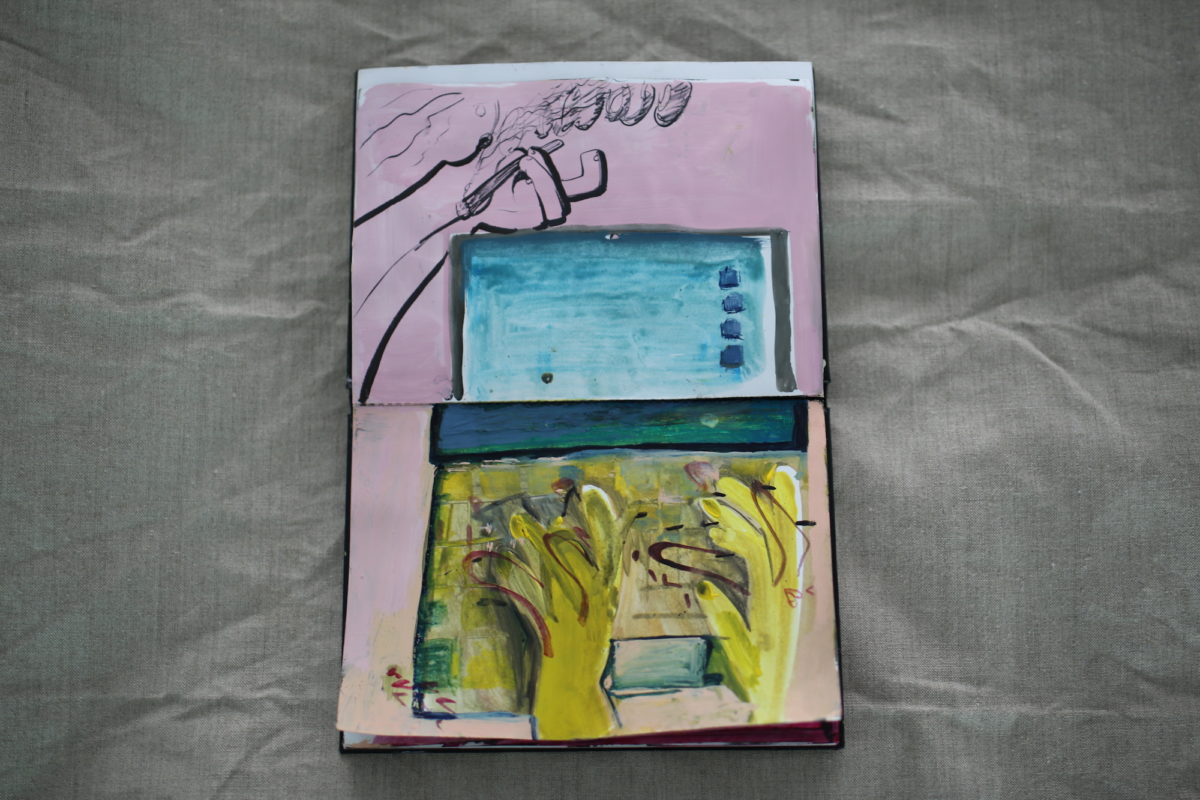

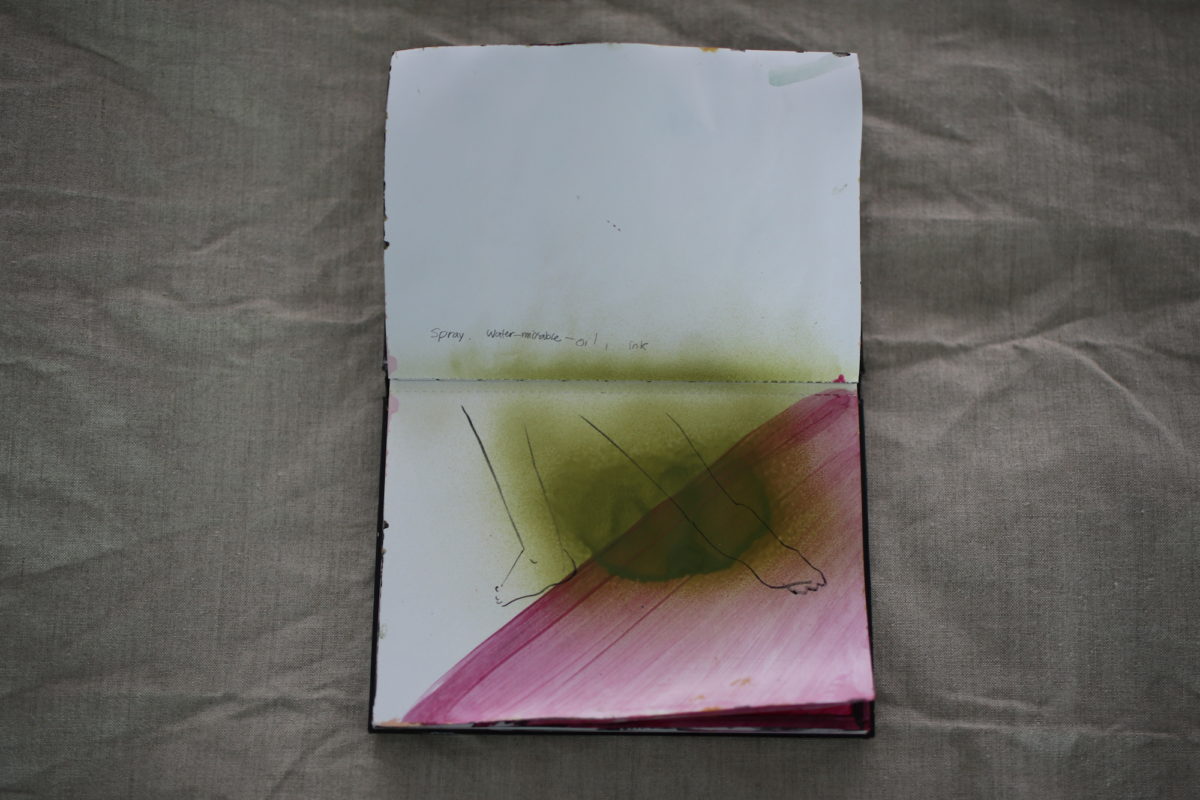

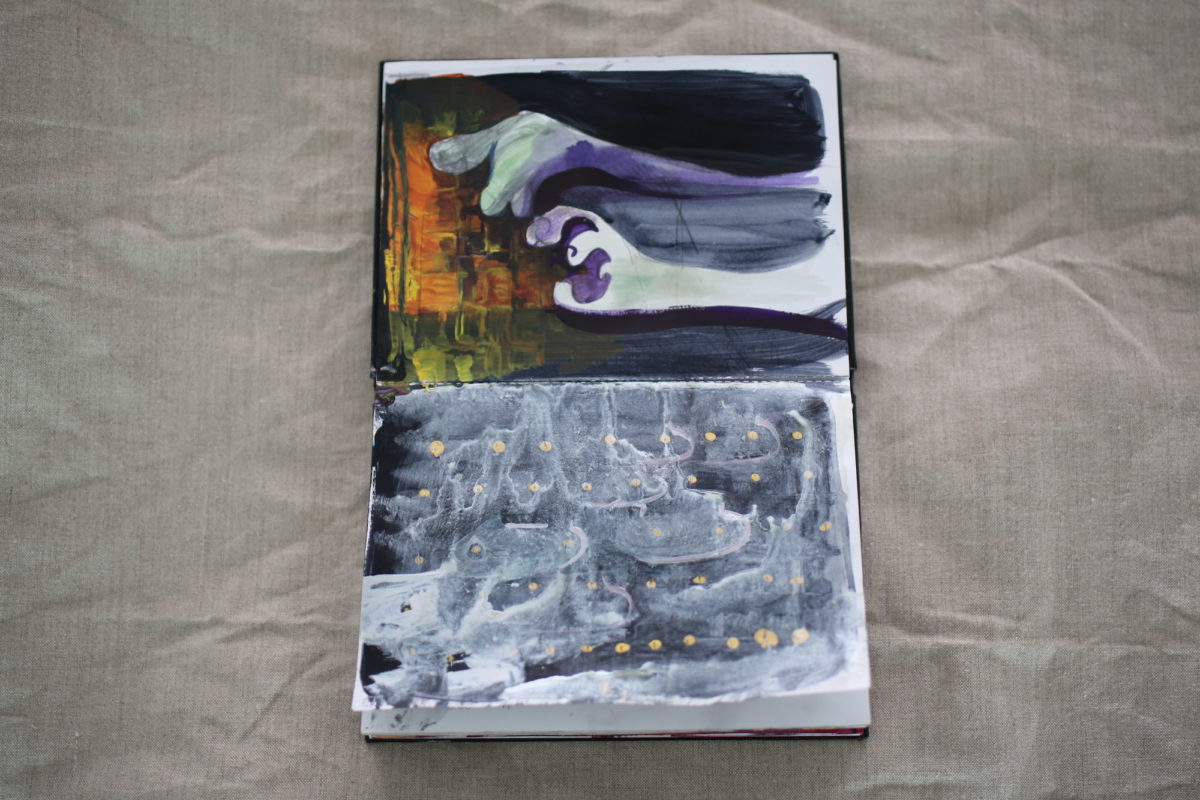

I’m always interested in exploring the relationship between image and language, and in how nuance of language can be delivered within the language of painting. For my work during the residency, I wanted to experiment with my unorthodox way of using Asian calligraphy in my paintings. Usually I’m a very colourful painter, but on the residency—perhaps because I was thinking about Asian ink painting—I’ve found myself reducing my colour palette and using this beautiful greyish-blue a lot.

It’s also been my first time using these Winsor & Newton water-based oil paints. I’ve found them so interesting to work with, because they have this thickness to them which I find very useful for changing the tones effectively. Before, I mainly worked with traditional oil and turpentine.

Tell me a bit more about the unusual calligraphy elements to these new works. They’re quite subtle additions to the paintings, and aren’t immediately obvious.

One way I incorporate the Asian calligraphy into my work is by using ink on top of the acrylic paint. The reason I love using calligraphy is that with just one stroke you can convey a different intensity. Sometimes it’s a kind of forcing, putting pressure intensely on the surface, and other times I’m releasing slowly with the brushstroke. It can mean a great change of mood; a great change of meaning.

“Speaking English as my second language was quite crucial for my painting, because it felt that painting became my most convenient language”

How would you describe the mood of your works?

I’m combining life and art quite often, which I think is particularly obvious here in my drinking pictures. I’m looking to convey the sensitivity we feel when we drink and when we smell; the sensitivity that meets the emotional quality of life. In these paintings I try to create a contrast between the background layer and the top layer, by using a lot of water and very thick paint to create different tones and layers. I’m trying to create these kinds of chains and layers of feeling: first you’ve got the glass which you touch, and then you pour the wine and touch the glass to your lips—there’s a lot of sensitivity and feeling to it.

It’s interesting that, while drinking is often portrayed as a very sociable activity, you capture moments here that feel deeply introspective and personal.

Yes, I try to capture the personal sensations in the different moments of drinking; here with sipping, the line shows the arc of movement of the liquid coming down the throat to the bottom of the body. Through all the different angles I try to capture and examine the moment of feeling the drink. At the end of the day, I sit down alone and have a drink by myself, and it’s a massive emotional ritual. That emotion cannot be felt when we drink socially. I see it as a personal moment.

Hands and feet are a repeated motif in your works. What is it about them that appeals to you?

I grew up in a traditional, quite conservative family in South Korea, and it’s considered quite intimate to show your bare feet. For me, feet feel like a very private part of the body. The idea of feet touching makes me think of lovers in bed, and I feel that feet represent a kind of personal honesty. Hands function similarly for me, but they symbolize a meaning that’s less private. In my paintings they often form gestures that are inviting. It’s hard sometimes to pin down in an image the language of the mobile body, especially because this language is often a euphemism and it can be hard to pinpoint what it means. I’m hoping to paint not so much reality as actuality.

You mentioned your South Korean conservative background. What led you to go into painting and into art?

I’ve always felt very comfortable painting. Every kid paints and then slowly, one by one, they just give up and find something else—but I never really stopped. Then I came to England eleven years ago to study at Goldsmith’s. Speaking English as my second language was quite crucial for my painting, because it felt that painting became my most convenient language; it became the way I could communicate and express myself. It’s hard for me to hide my feelings and emotions and I think looking at other people’s paintings helped me to draw on the power of mutuality, and helped me to learn how they were feeling from their painting. For me, painting is language.

“After eleven years, I’m finally feeling at home here, but that happy moment was followed by a kind of sadness. It’s a moment that’s not entirely positive or negative, but sort of tragicomic”

What’s next for you?

I’m still doing my PHD at the Slade, but I’m almost finished! I want to stay in the UK, I’ve been here too long to leave. I feel at home here, which is actually a really new feeling. I still feel very good about going back to South Korea but last winter, when I was there for a few weeks, for the first time I kept thinking “I want to go home to London.” After eleven years, I’m finally feeling at home here, but that happy moment was followed by a kind of sadness and a worry that I’m betraying my parents whose home is still South Korea. So it’s a moment that’s not entirely positive or negative, but sort of tragicomic. I often have these moments, and I think it can be seen in my paintings; I’m making tragicomic paintings.

What has been your experience of the residency?

Everyone has been so supportive! I’ve had the opportunity to use all the materials I would never think to buy myself, and all the support I’ve received has given me such a rare freedom. It’s been really special, just being able to clear my mind of all the practical concerns that I normally have to consider. I’m a very curious person, and I was able to follow through on all my little curiosities and make work out of it.

Photographs by Louise Benson

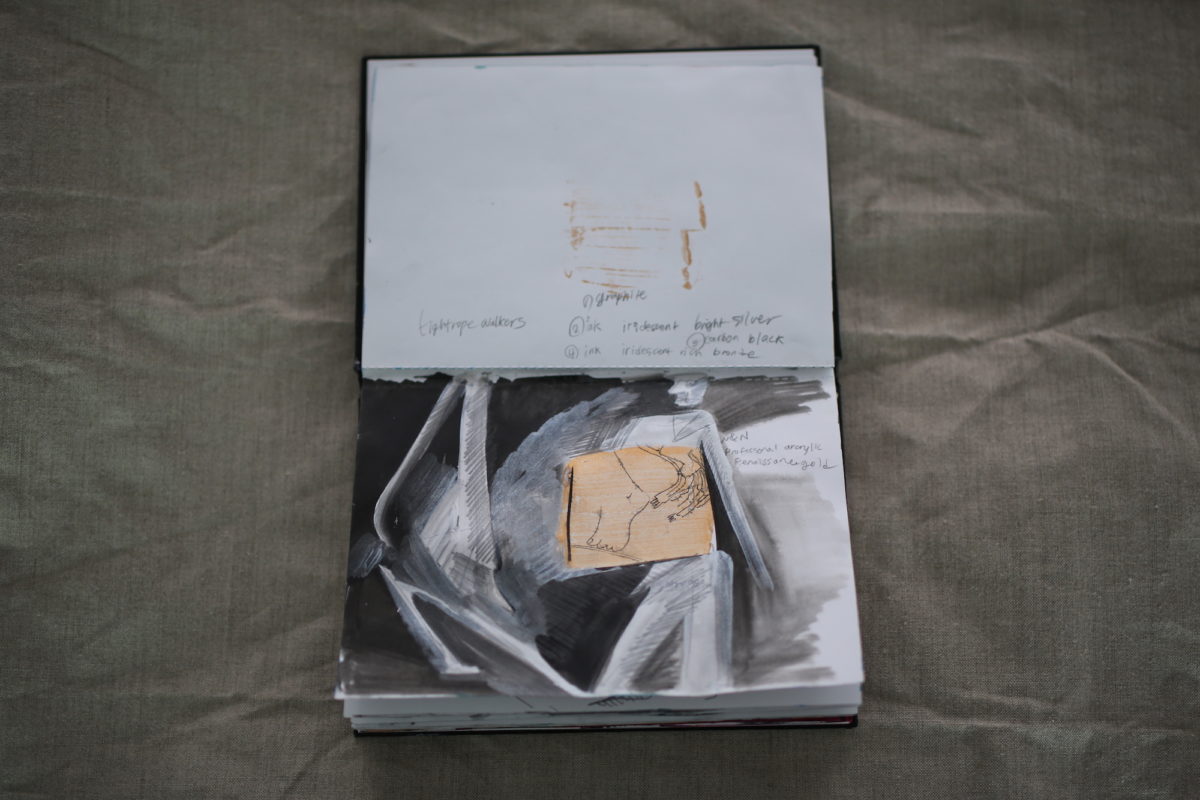

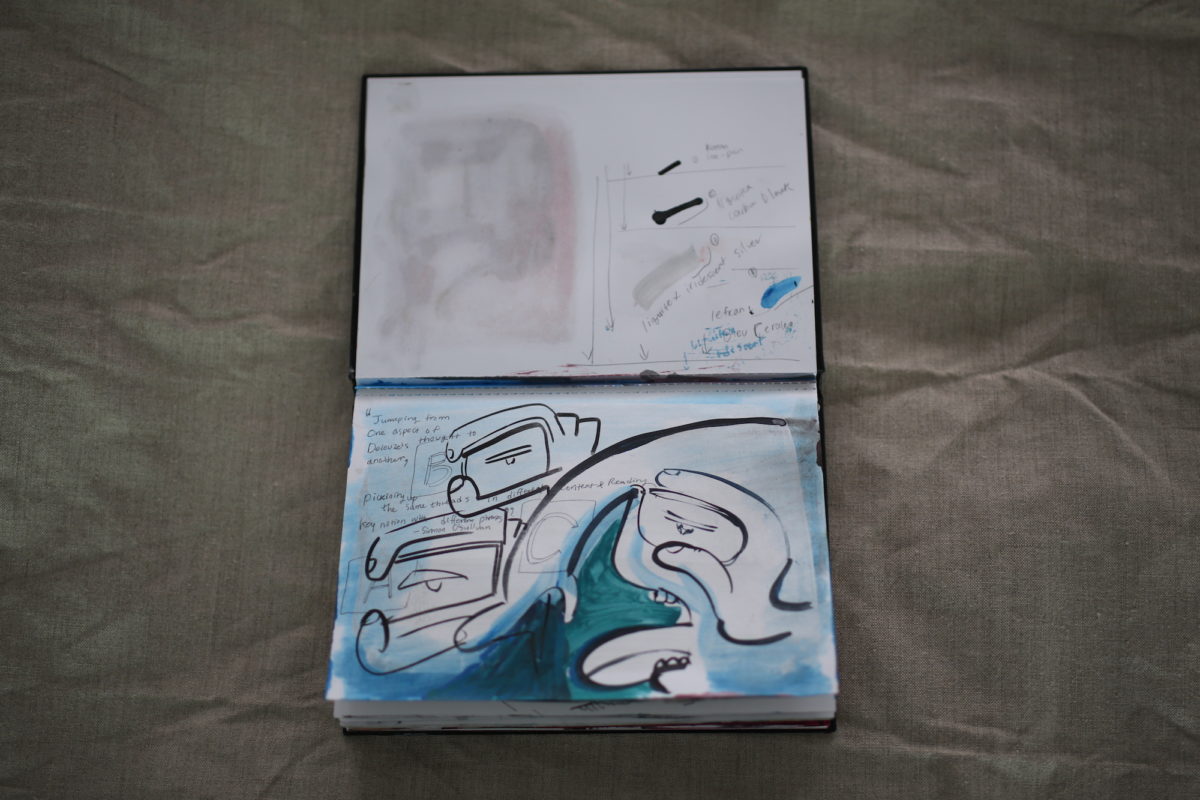

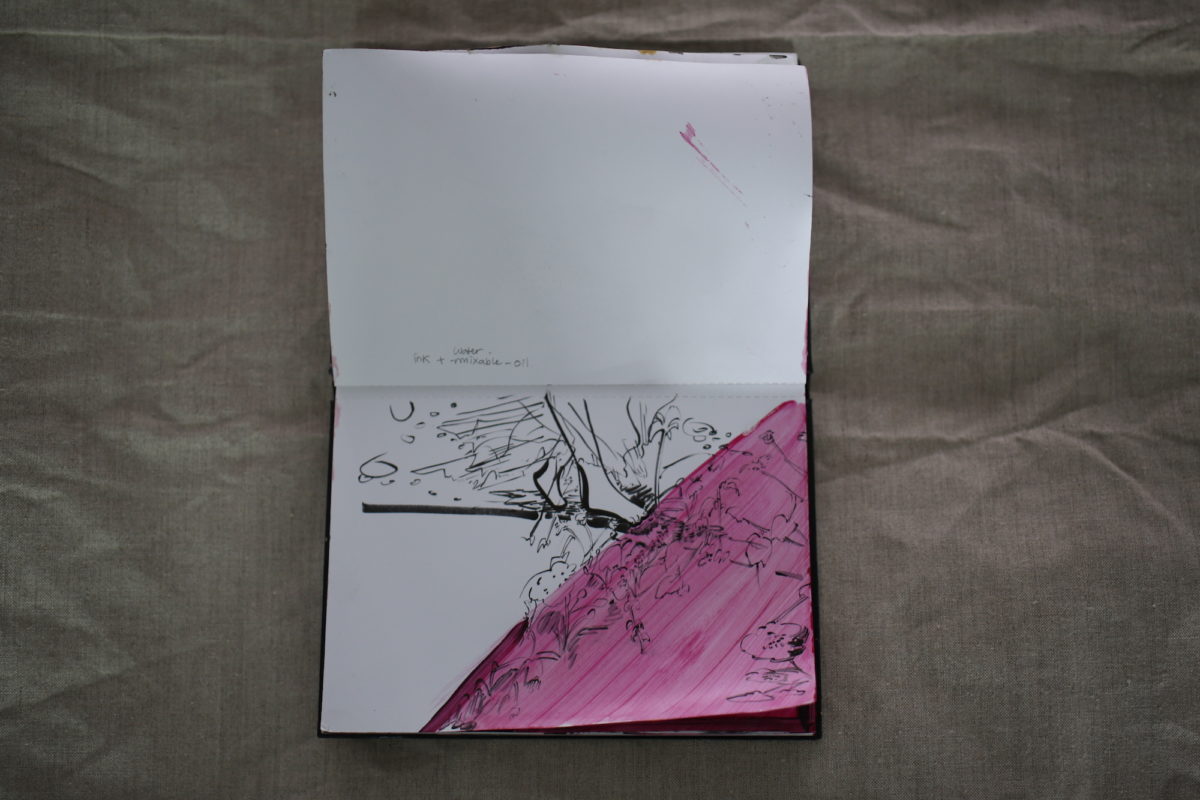

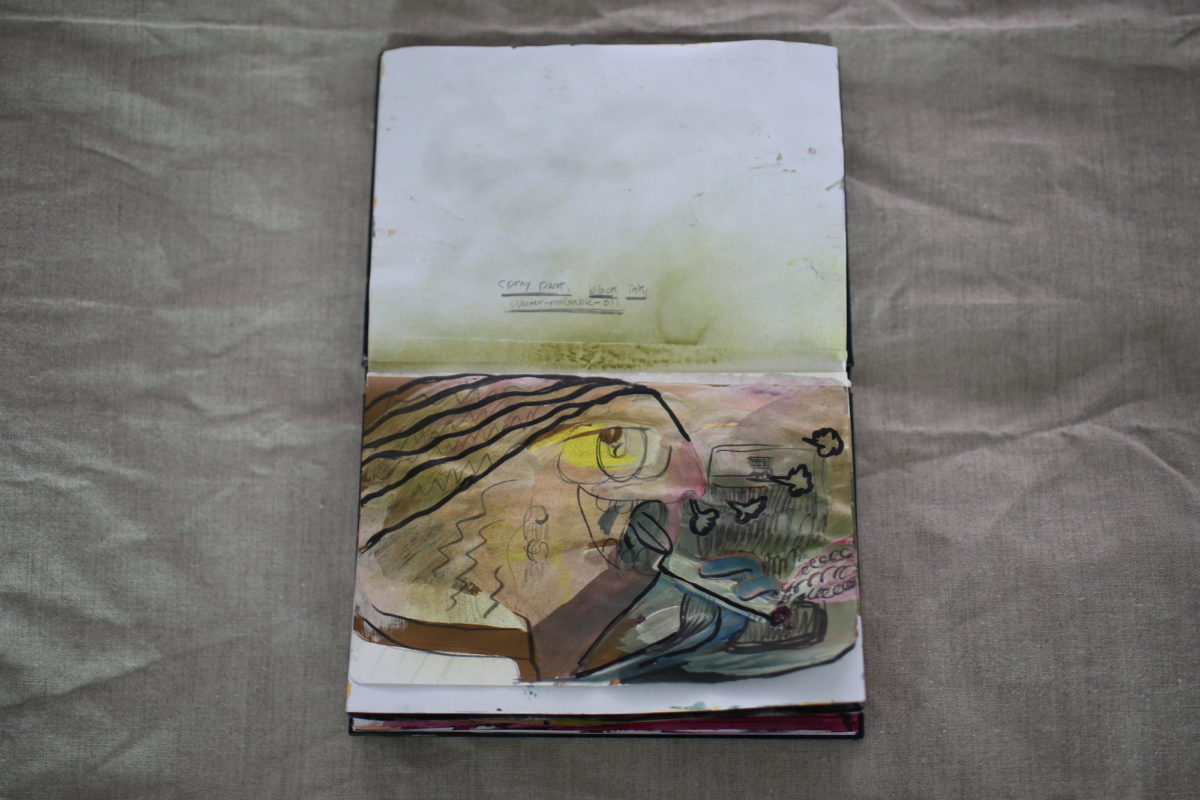

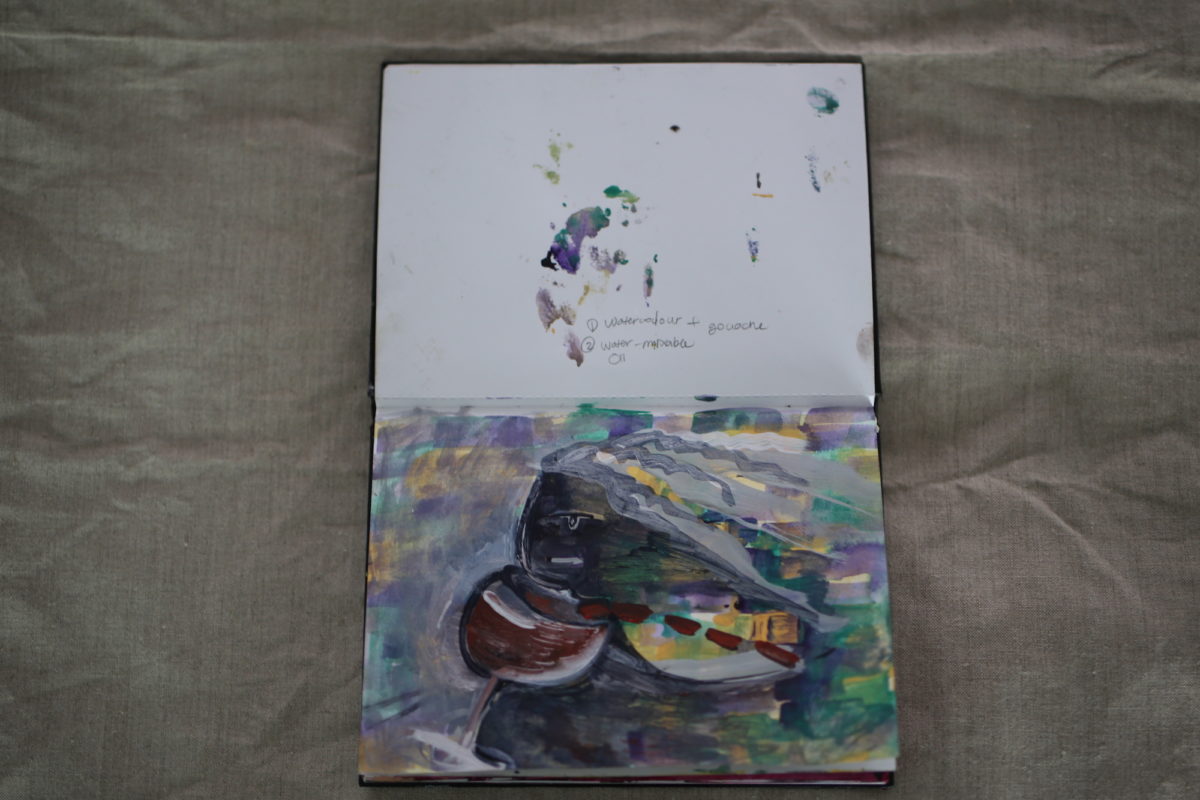

All artists-in-residence are invited to document their time at the Elephant Lab in a Winsor & Newton sketchbook, filling it with drawings, paint samples, odds-and-ends and other personal reflections. This is Jin Han Lee’s.

Residencies at Elephant Lab

Practising artists are invited to make proposals for a one month residency at Elephant Lab

VISIT WEBSITE