One of the highlights of the Frieze Masters Spotlight section for late-career artists deemed worthy of attention year was undoubtedly a stand of larger-than-life nude paintings by Joan Semmel (b. 1932, New York City). Instead of working from sketches, Semmel takes photographs of herself, looking down on her body, creating an extremely foreshortened figure zoomed in close, often to the point of abstraction, colourful and collaged, taken from angles known intimately only to the subject herself, overlaid and sometimes wrinkled—the body of an older woman. These self-portraits are exploratory yet knowing, showing the body as beautiful yet far from the nude. While spilling out of the frame in a similar fashion, there is none of the abjectness of Jenny Saville, none of the crudeness of Courbet, none of the raw animal fleshiness of Bacon, none of the passivity of Freud. These are women’s bodies portrayed lovingly, sexually, sensually, unflinchingly and with ownership.

“I wanted to create sexual images that were erotic for women that did not satisfy only the male appetite, which is dealt with in most pornography”

Although present on the art scene since the sixties—she forged a successful career as an abstract expressionist, working for seven years in Madrid (1963-70), before returning to the US and becoming involved in the feminist movement and art groups of seventies New York—Semmel has been moving back into the spotlight for the last five or six years. “It is too soon for me to know how much the Frieze exposure will mean,” she says when we meet a couple of months later. “But I was deeply gratified by the response of the public and collectors and curators who attended both the booth and the talks.”

Returning to New York from Spain with two young children in the early seventies, Semmel was, she says, looking for the “sexual revolution”. “My way of working and my ideas shifted radically. I wanted my work to directly reflect the issues in which I was involved. I found a loft in SoHo and made it livable, got a divorce, enrolled in the graduate programme at Pratt so that I would be qualified to teach and earned just enough money through odd teaching jobs and a fellowship. It was a scary and precarious time. I began attending political meetings at the Art Workers Coalition, the Ad Hoc Women Artists Committee and various other women’s groups. Instead of revolution, however, Semmel found what she describes as sexual commercialization that mostly showed female bodies for sale. In response, she strove to find an erotic visual language that would speak to women. “I wanted to create sexual images that were erotic for women that did not satisfy only the male appetite, which is dealt with in most pornography,” she recalls. “To do that I needed to get images made from drawings or photos from life that were not posed, so that the preconceived ideas were not determining the results.”

Within a couple of years of her return, Semmel produced two series of large sexual works: Sex Paintings (1971), made from drawings, and the Erotic Series (or “Fuck Paintings”, 1972-73), for which she first began to use a camera, albeit, at this stage, pointed towards other people. “Back then there were a lot of these swinging clubs, and people were experimenting with all kinds of stuff. So, for us, it was an opportunity,” says Semmel. She had begun drawing already from her imagination, but a friend suggested she draw from life and, reams of action drawings later, she was trusted enough to take a camera into the club with her. “They knew I wasn’t going to be publishing any of it as sex photographs, that I was using it for paintings, and so I was able to take the photos myself. I was really fired up and worked fast. [My work] was shocking and got considerable attention, but it was very well received critically. I couldn’t get a gallery to show the sexual pictures, so I rented a space and showed them myself. I had pretty high visibility during that time, my name was known and I had a lot of reviews.”

Despite the shift to moderate figuration—Semmel is uncomfortable being described as either a realist or a figurative painter—colour was retained as a primary element in her work. This served as a distancing device defining the object as art and separating it from the realm of pornography. As she moved away from sexuality as a theme, and began to utilise self-nudes, Semmel’s palette gradually became more naturalistic, but she continued to use the camera as a tool to locate and structure the image. “I was never focused on self-representation but rather on finding a way of re-imagining the nude without objectifying the person.”

At the time, Semmel was primarily addressing the religious and cultural restrictions she saw imposed against any kind of bodily exposure, and the modesty in attire and attitude enforced by shame. A good woman was not supposed to look sexy or, for that matter, express desire, she says. Today it’s almost a complete reversal. A young woman now needs to satisfy male sexual fantasies by turning herself into a walking fetish object. If she doesn’t do this, she isn’t hot and desirable sexually, which still seems to be promoted as her primary function. Turning the camera on herself and using a mirror were, for Semmel, strategies for destabilizing the point of view (who is looking at whom) and engaging the viewer as a participant. It remained, however, much more about self-creation than accepting how one is seen by others. In the catalogue for her most recent exhibition (Joan Semmel: New Work, 2016) at Alexander Gray Associates, Semmel writes: “A woman’s body has been experienced for so long as a burden to be borne, and age as a disease to be feared. At this time when so many strides in medicine and health have taken place, these same cultural attitudes still seem to prevail and are cultivated by many diverse commercial interests. The constant exploitation of the image of the female body of a certain age and predetermined shape as that most coveted object of desire leaves us divided from our own selves. We have learned to desire that very same image and try to cajole and squeeze ourselves into its outlines.”

When she first went over to the self-image, Semmel made two pictures of herself with a partner, post-coital. Unlike her Sex Paintings and Erotic Series, however, they were “fudged”. “I used a photograph from each partner separately, and then I put them together, so they each had their own disappearing point. I like that because of what it signifies in terms of autonomy. For my generation, that was a really important thing for a woman, to not lose herself in a sexual engagement completely—that you can enjoy and everything but not give over to the point where you’re just working on his desires and none of your own.”

Looking back on her own life, Semmel reflects: “As a young girl, I had the usual insecurities about my appearance and body. I am not immune to the culturation process. Using myself as a model forced me to ignore those worries. I don’t know if I am any healthier for the process. I am always asked the question about my feelings of being publicly naked, and I always answer it isn’t me, it’s the painting. The work forced me to lose my self-consciousness. My focus was on the history of women and the ‘nude’, and how women internalize the messages they receive from art, fashion and Hollywood.”

Taking photographs of herself in the mirror, the camera is simultaneously turned round to point at the audience and this, importantly for Semmel, also reverses the gaze. I am an artist, I am a feminist, I am a feminist artist. I cannot be one without the other, she says. Many feminist artists in the seventies rejected painting as their medium, but Semmel stood fast. “Painting is less immediate and requires a different kind of competence in order to be successful,” she says. “It has been a field traditionally closed to women except as amateurs. Figurative art, in particular, has not been fashionable in recent years and the exploration of other ways of making art has expanded. The heroic romance of the male artist painting a naked female, preferably also having had sex with her before or after, is not inspiring for women artists. Imagine oneself naked, painting in front of a mirror. Not fun.” Nevertheless, that is precisely what she does.

As she has got older, Semmel’s image has aged with her. “I am older so the image is older and the subject becomes the flesh and perhaps mortality. Mortality is always sobering. To deny vulnerability is to deny reality. Vulnerability is there.” Recently Semmel has experimented with blurring her imagery. “I tried to take my own pictures using a timer on the camera and then racing to be in front of the lens,” she explains. “Consequently, many of these photos were blurred and images doubled.” This trope, carried over into the painting itself, functions both aesthetically and metaphorically, suggesting motion and time passing, a way of visualizing the inevitability of ageing. The image, the body, the woman is not a static object but something that moves in space and time. Semmel has also used layered transparencies to act as a screen or veil, as “a kind of layering of memory, of how you understand yourself as you are and as you were and as you will be“.

“A good woman was not supposed to look sexy or, for that matter, express desire. Today it’s almost a complete reversal. A young woman now needs to satisfy male sexual fantasies by turning herself into a walking fetish object”

Semmel doesn’t set out with any preconceptions of what she seeks to capture, rather she lets the painting speak to her in the process of creation. The idea of intimacy is something that she particularly responds to, both between people and between the painting and the viewer. Her closeup, cropped paintings have been seen by many as treating the body almost more as a landscape than as a figure, but Semmel doesn’t see it this way. “I don’t see the body of woman as nature in the nature/culture dichotomy. It is most definitely about culture for me. Furthermore, the connection to the flesh is key. For better or worse, [it is] always with us. The flesh permits us to fully experience our common humanity.”

Today, Semmel is professor emeritus of painting at Rutgers University and lectures nationally and internationally. In the early seventies, she taught one of the first classes on women artists there. “I didn’t have to teach a lecture class; I only had to teach painting. But I told them I wanted do a class on women artists. There weren’t any books on any of it! I went around collecting slides from different shows where women were showing. I had to find essays and writing. And I researched what there was in the past, back to what some of the nuns had done. It was an educational process for me, too. I would mimeograph the pages to distribute the lessons, the writings. There were no books. And this was only fifty years ago.” But Semmel notes how much still needs to be done: “Things have changed a lot, especially in urban centres. However, it will take a long time to change cultural norms and it will be the proverbial rolling the ball up the hill. The recent election shows how much still needs to be done.” Sisyphean or not, Semmel’s contributions and legacy will not go unnoticed.

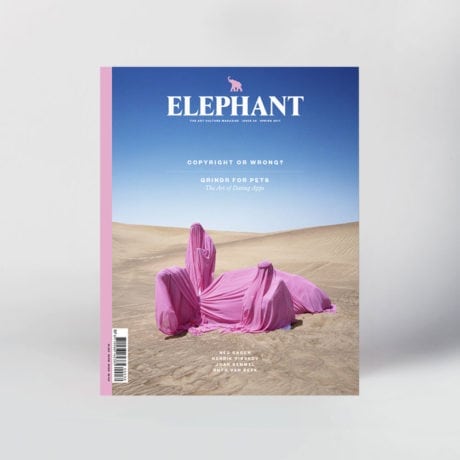

This feature originally appeared in issue 30

BUY ISSUE 30