For most people, the ongoing pandemic and part closure of the world has been a profoundly destabilising experience. Systems, routines and conveniences on which many relied—often unconsciously—have been unceremoniously stripped away by a silent, invisible and seemingly unpredictable new agent in the game of life and living. The abrupt cessation of “normal” has led some to reach out into older or simpler systems and practices, like foraging and small-scale cultivation; activities which rely on the human body and mind, and a connection to natural and elemental processes. They also generously allow for the interposition of chance.

“The abrupt cessation ‘normal’ has led some to reach out into older or simpler systems and practices”

It seems appropriate then, that a new book has been released by Atelier Éditions, including the compositions, diary entries and “indeterminacies” of composer and mushroomer John Cage, often considered a foundational figure in the development of Western contemporary art, and famous in mycological circles as a skilled, passionate forager and cook. At one time, he supported himself by supplying New York’s best restaurants. His compositional and choreographic practice was rooted in collaboration, in the act of listening to whatever sounds presented themselves, and in employing chance interventions when creating structures. He had a meditative relationship with fungi. “It is useless,” he wrote, “to pretend to know mushrooms. They escape your erudition.”

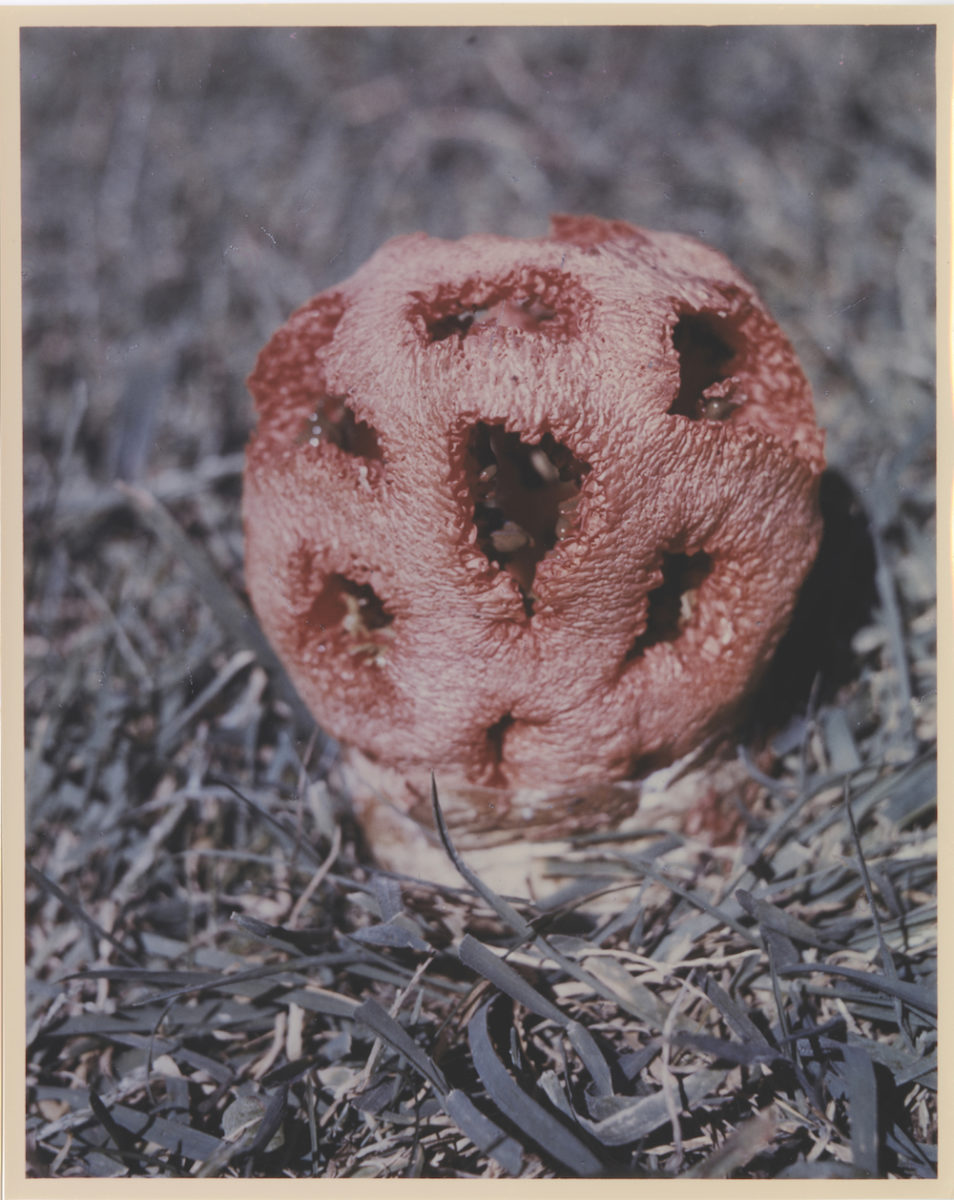

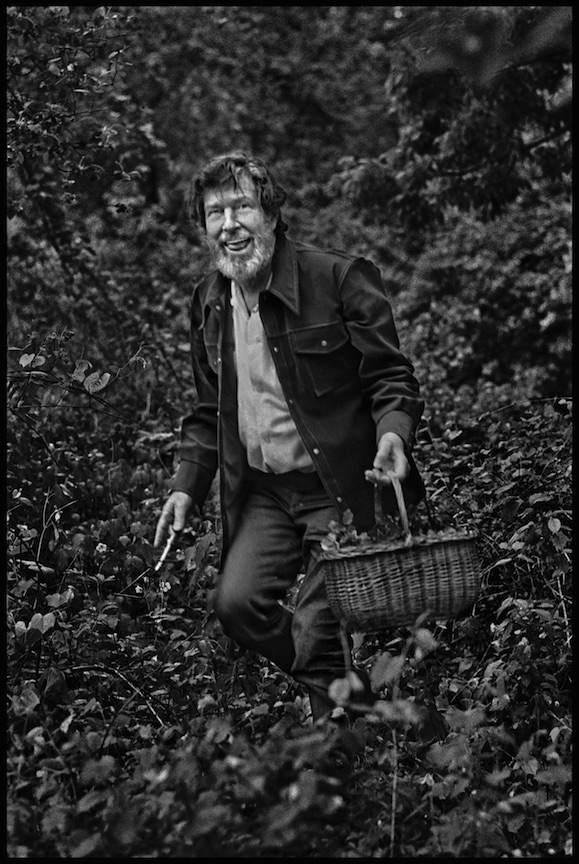

- Photographs collected by John Cage. Photographers unknown, n.d. Courtesy of the John Cage Mycology Collection, University of California Santa Cruz Special Collections and Archives

Yet it is important to be able to recognise mushrooms; failing to do so accurately can result in sickness and death. For Cage, learning to recognise different types was not only a lucrative, nutritious and meditative practice, it was also educational. Along with chess, it formed a kind of grounding activity for a life lived on a cumulus swirl of contingency. Mushrooms can teach people to look with a clear and singular eye, seeing each thing as its own centre. They can bring about a meditative state and provide supper.

Cage wanted his class on mushroom identification at the New School to teach students to observe and appreciate the thing in and of itself, and not through its relationships to other things. He hoped this would encourage them to look at life, art and education in the same way. The never-ending quest to refine fungi identification abilities provided an excellent metaphor for his commitment to the idea of life-long learning. “Education is of no value unless it is sustained throughout life… And this is why not only I but now many more people say our proper business is revolution.” If Cage’s habits as a host were anything to go by, it would be a revolution fed on fungi.

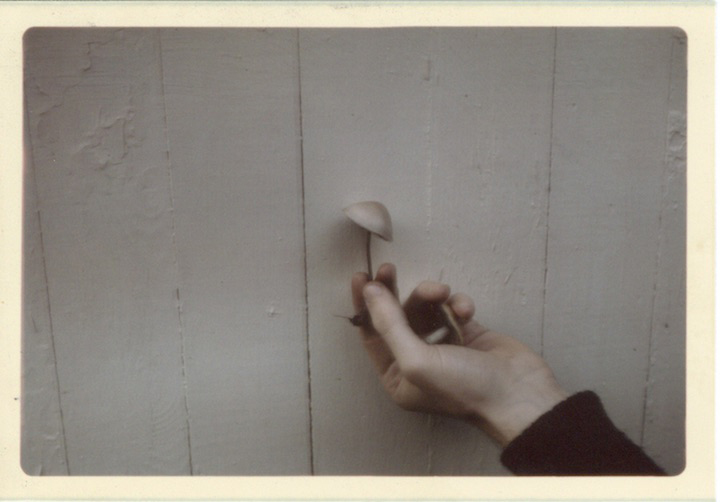

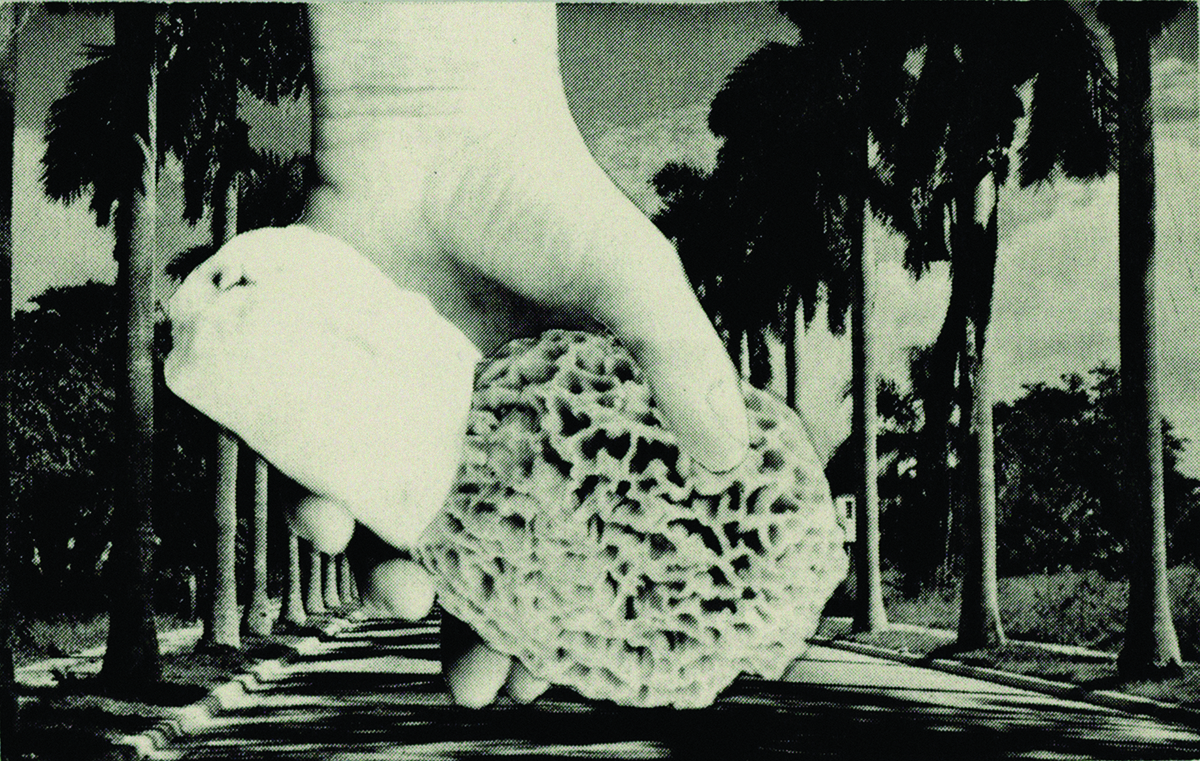

- Photographs collected by John Cage. Photographers unknown, n.d. Courtesy of the John Cage Mycology Collection, University of California Santa Cruz Special Collections and Archives

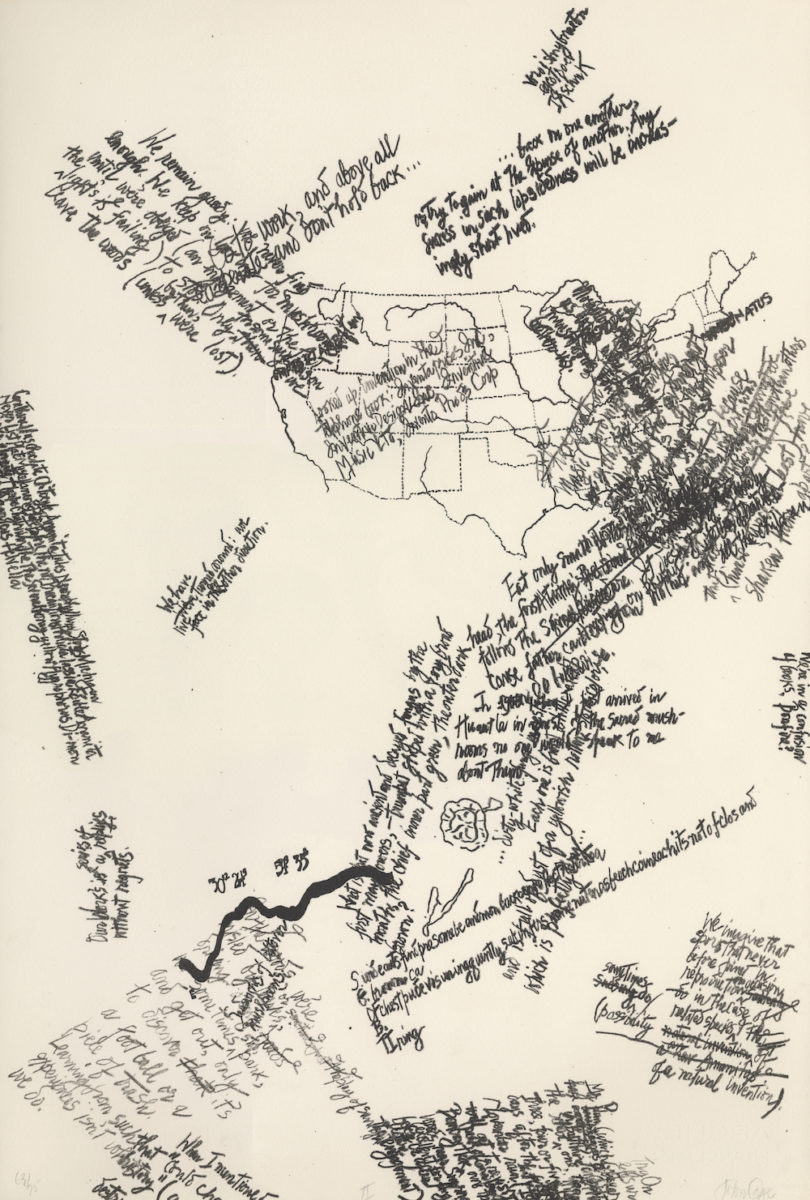

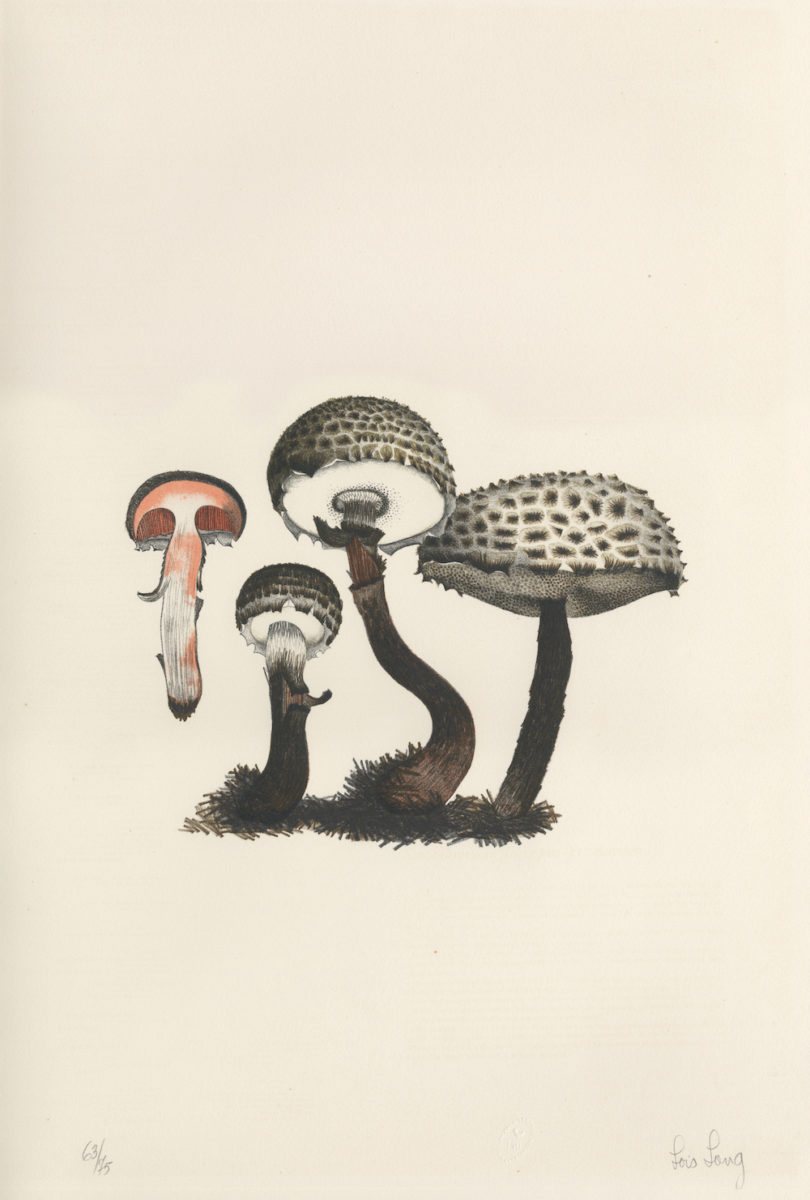

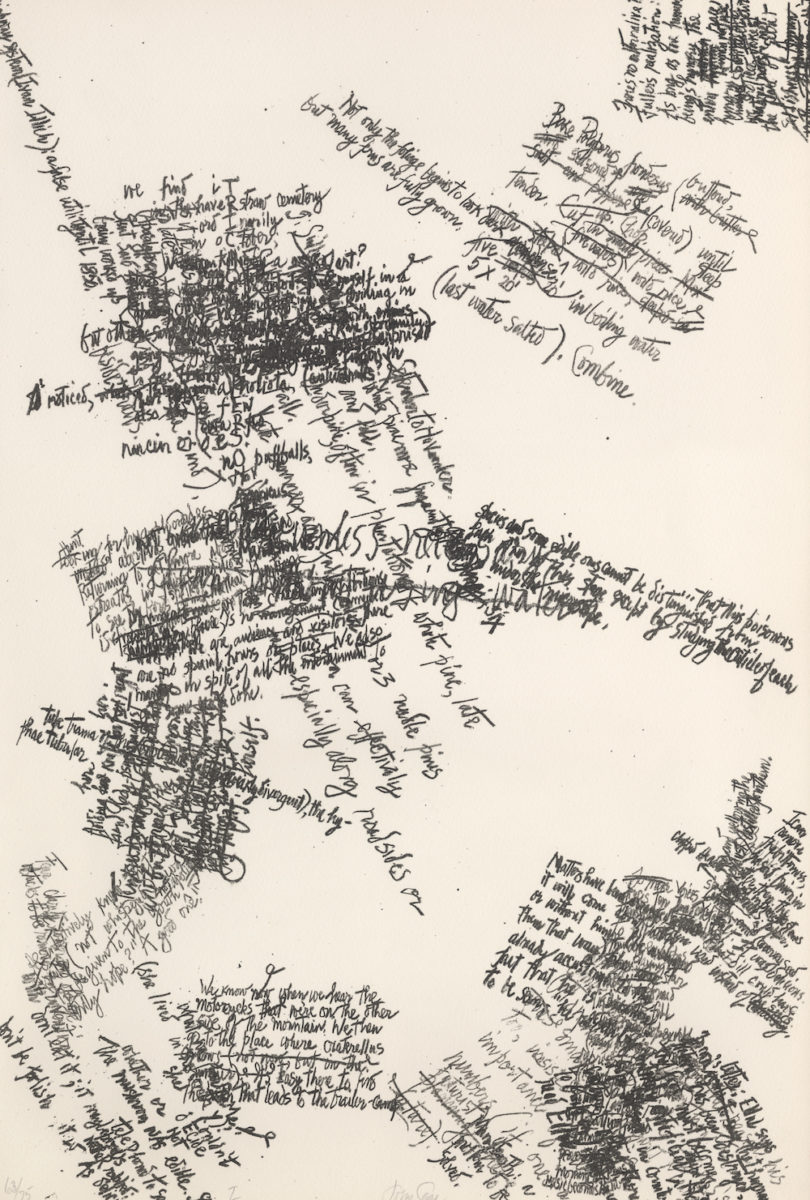

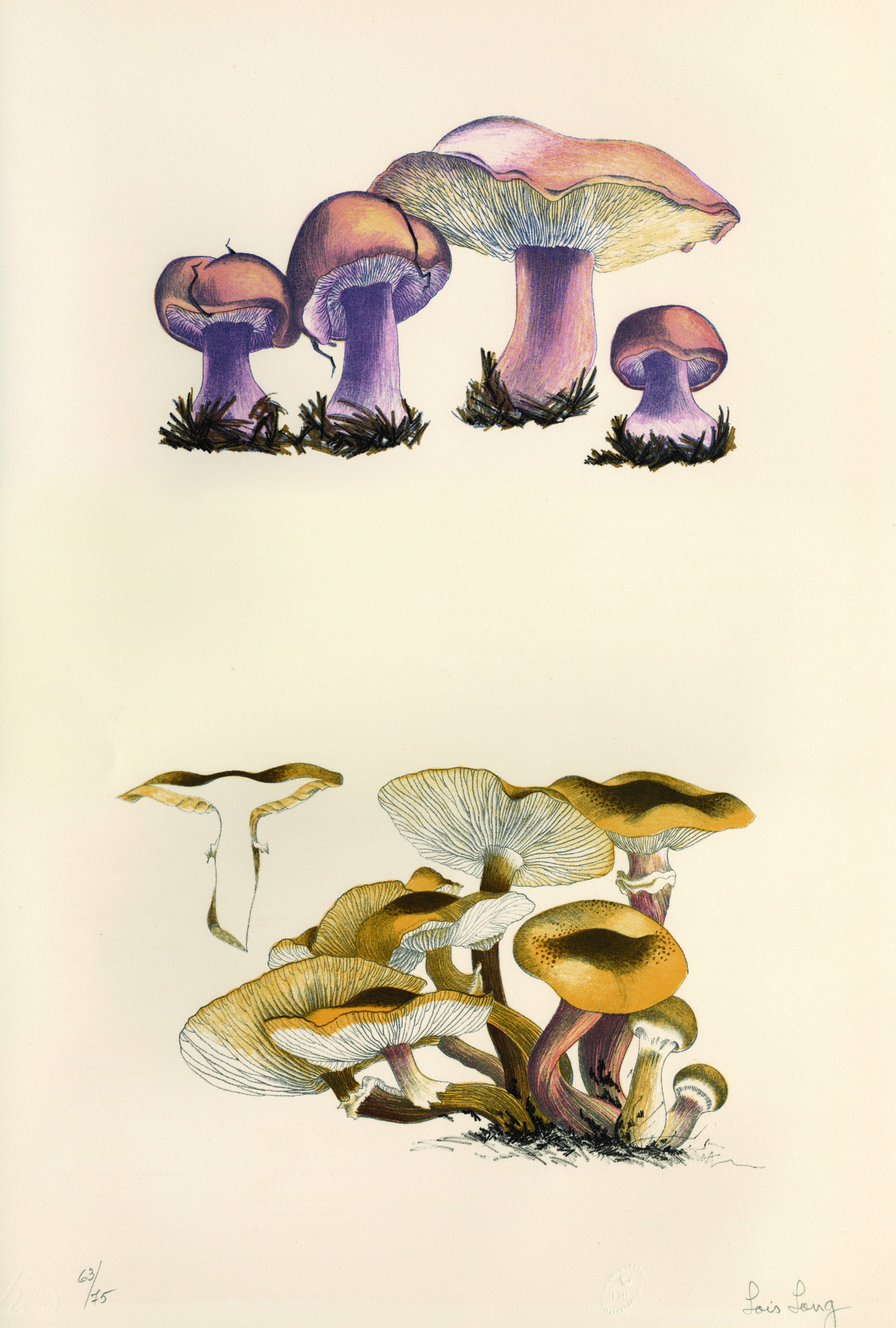

Bringing together essays, excerpts and the complete transcript of Cage’s 1983 performance Mushrooms et Variationes, Atelier Editions’ two-volume publication both assesses and re-embodies the artist’s mycophilia, which has been long looked on as a curious quirk of his personality rather than an integral part of his practice and philosophy. Beautifully illustrated with photographs and artworks of, by, and collected by Cage, the publication also puts the spidery scribbles of the multi-layered Mushroom Book (Cage’s anecdotal collaboration with illustrator Lois Long and botanist Alexander H Smith) into the readers’ hands, providing the chance to appreciate Long’s finely accurate botanical drawings and the trio’s little notes about Suzuki, music, poison and myths. The reproduction encourages us to try and forage through Cage’s sprawled, overlapping notes for whichever nugget of mycological or musical insight we manage to chance on that day.

“Mushrooms can teach people to look with a clear and singular eye, seeing each thing as its own centre”

The activity of the amateur mushroom forager was, for Cage’s reformed Mycological Club, a way “to affirm this life, not to bring order out of a chaos nor to suggest improvements to creation, but simply to wake up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of the way and lets it act of its own accord.” The pictures of the artist which accompany the text show a man who, despite living through the vagaries of the Great Depression, the cultural revolution of the 60s, and everything in between, finds life an excellent and worthwhile experience, full of companionship, art and mushrooms.

- Mushroom Book, 1972. Scan of 63/75, Plate II. Artwork by John Cage (left); Scan of 63/75, Plate II. Artwork by Lois Long (centre); Scan of 63/75, Plate I. Artwork by John Cage (right). Courtesy the John Cage Trust

In a world where it often seems as though previously harmonious relationships between things are becoming frayed at the seams, Cage’s commitment to foraging as a tool for developing a sense of finely balanced internal stability seems worth a re-visit. As he put it: “I am not interested in the relationships between sounds and mushrooms any more than I am interested in the relationships between sounds and other sounds. These would involve an introduction of logic that is not only out of place in the world but time consuming. We live in a situation demanding ever greater earnestness… It behoves us therefore to see each thing directly as it is, be it the sound of tin whistle or the elegant Lepiota procera.”

In the devastatingly titled Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse), Cage wrote, “a meal without mushrooms is like a day without rain”. Excerpts from this book are scattered throughout John Cage: A Mycological Foray, painting a picture of a man whose wander through life—punctuated by dinner parties, chess with Duchamp and pauses for mushroom picking—has a lot to teach us about how to find joy through simply being in the world, even when the world is at its most narratively random, and materially raw.