The mushrooms are coming. Not “overnight, very whitely, discreetly” a la Sylvia Plath, but heralded by press releases. From exhibitions to skincare products, festivals to coffee additives, mushrooms are participating increasingly visibly in our culture. Of course, for some people, mushrooms are not news. For these mushroom people—mycologists, oncologists, herbalists, dermatologists, foragers, botanists, bartenders, shamans, biochemists and more—the headline is that the rest of the world is finally waking up to the weird, underground, in-between world of mushrooms.

The “mushroom people” are a funny crowd. There’s Roger Phillips, a whip-smart world-expert who has a penchant for dotted red berets which make him look like a fly agaric. There’s Atilla Fődi, a Hungarian academic currently working on translating the oldest known guide to mushrooms from Chinese to English. There’s Alexandra Sazonova and Chloe Ting, the Saint Martin’s grads who last year hosted Fungi Fest 2019—a day-long extravaganza of all things mushroom at the Hoxton Docks. There’s ethnographer Anna Tsing and public intellectual Paul Stamets. And then there’s my father, Martin Powell, a biochemist and Chinese herbalist whose clinical guide to the medicinal uses of various mushrooms was my first ever copy-editing job.

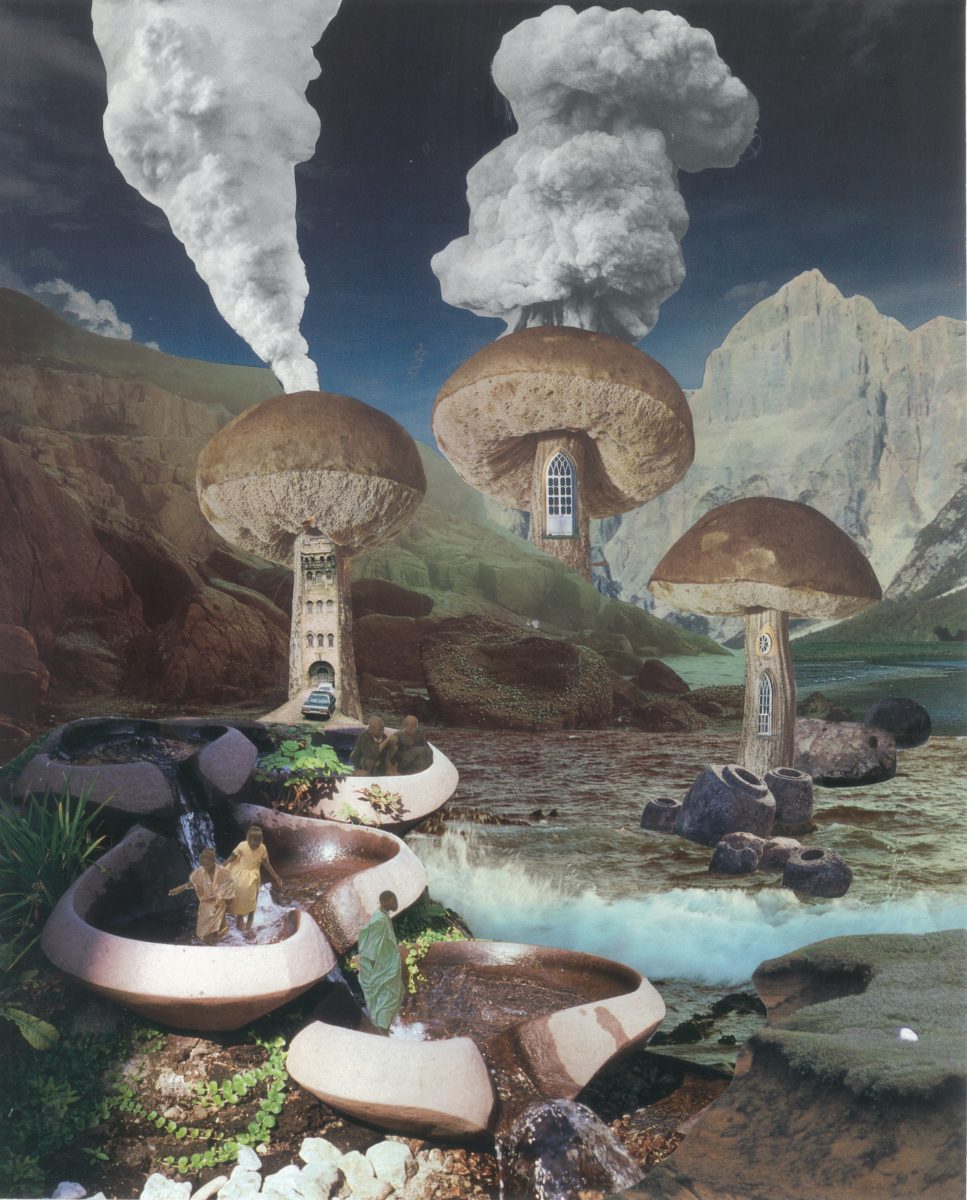

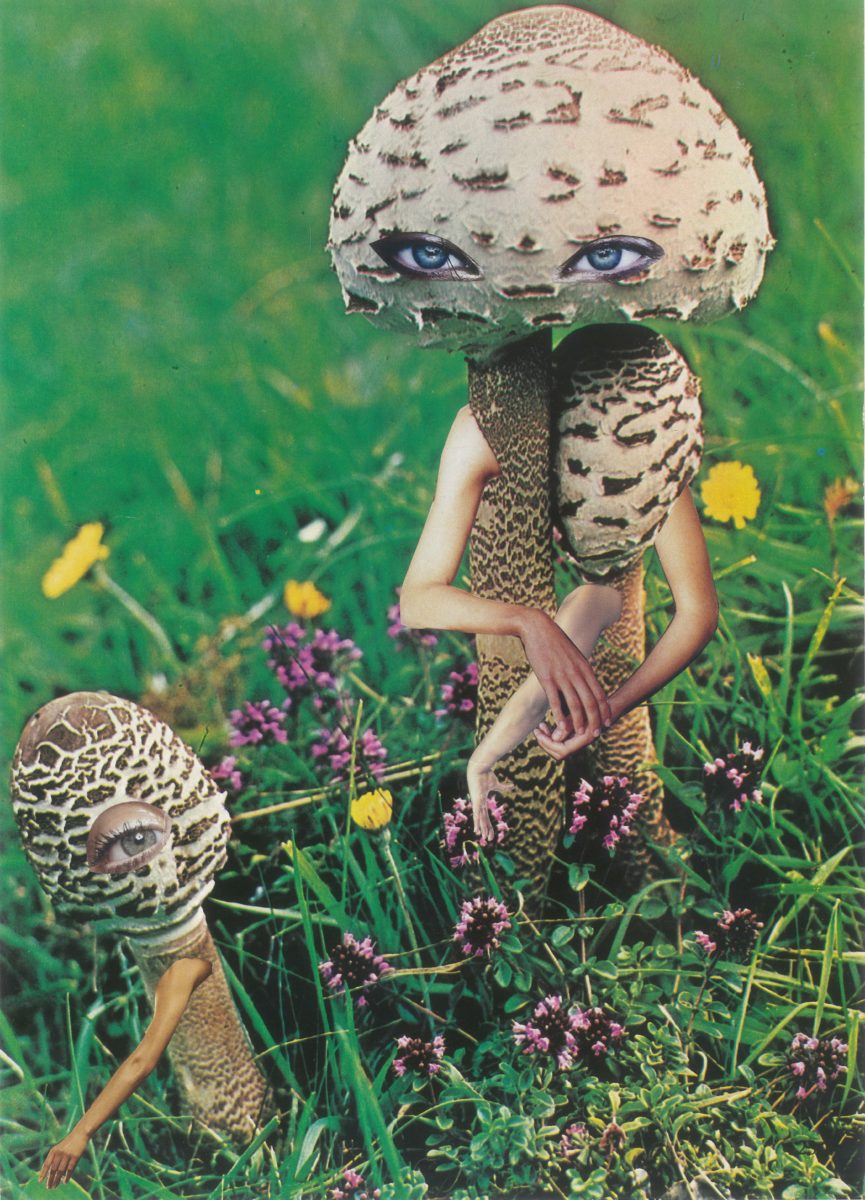

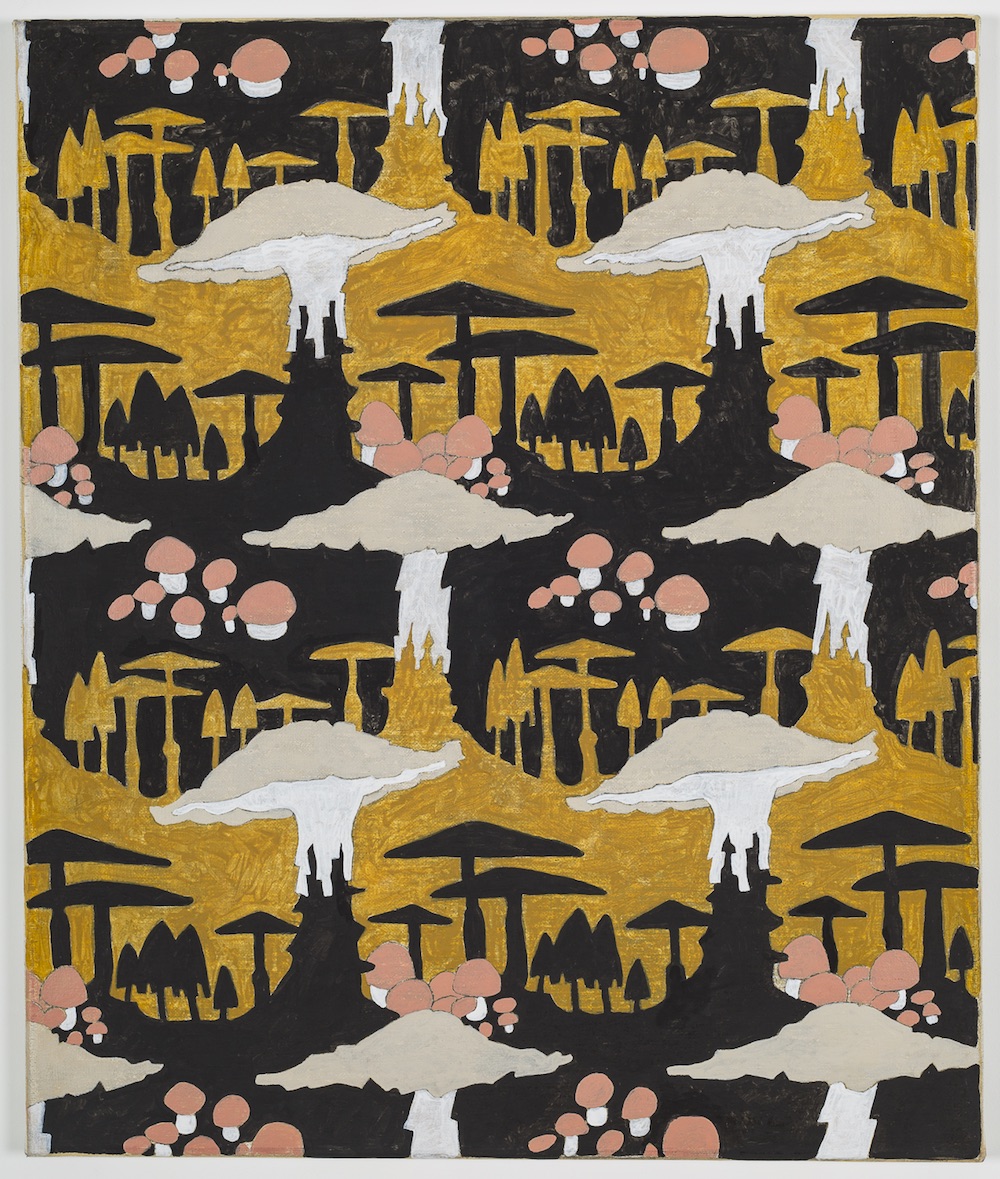

- Seana Gavin, Untitled Mushroom (left); Mushroom and Child (right) © Seana Gavin

Growing up, mushrooms were everywhere. They were in his shop in Neal’s Yard, way back when that was a plausible space for a small business to rent a storefront. They were dried in huge jars in our living room and kitchen. They paid for our fun. Eventually they were work—long summers spent encapsulating concentrated extracts and powdered biomass into little gel pills, bottling, labelling, heat sealing, shipping. If you’ve ever wondered how your supplements get made, sometimes it’s a fifteen year old girl in a small lab by the sea getting absolutely covered in spores. And once you’re a mushroom person you can’t escape. Last midwinter I went into the woods for mistletoe and came back with handfuls of Auricula auricularia. My father was incredibly proud.

“Even the sublime horror of an atomic blast sits in perpetual tension with the practically comic mushroom shape of its cloud”

Perhaps surprisingly, given all that exposure, I’ve never really thought in depth about the visual or aesthetic aspect of mushrooms and fungi. I suspect that’s because mushrooms are fundamentally rather silly looking. Bulbous, fleshy, profoundly organic, and yet lacking the je ne sais quoi of the “cooler” organisms. When they are phallic they are absurd, when they aren’t they’re not much easier to take seriously. Even the sublime horror of an atomic blast sits in perpetual tension with the practically comic mushroom shape of its cloud; a tension which no doubt contributed to its iconic status as an image.

Microscopic enlargements can be mesmerising, spore prints can be gorgeous, and the colours of certain species are some of the most vibrant found in nature. Some even glow in the dark. And yet they’re just a bit… kitsch. Probably some combination of Victorian fairytale illustrations and Super Mario is to blame, but whatever the source it’s hard to escape those associations.

Microscopic enlargements can be mesmerising, spore prints can be gorgeous, and the colours of certain species are some of the most vibrant found in nature. Some even glow in the dark. And yet they’re just a bit… kitsch. Probably some combination of Victorian fairytale illustrations and Super Mario is to blame, but whatever the source it’s hard to escape those associations.

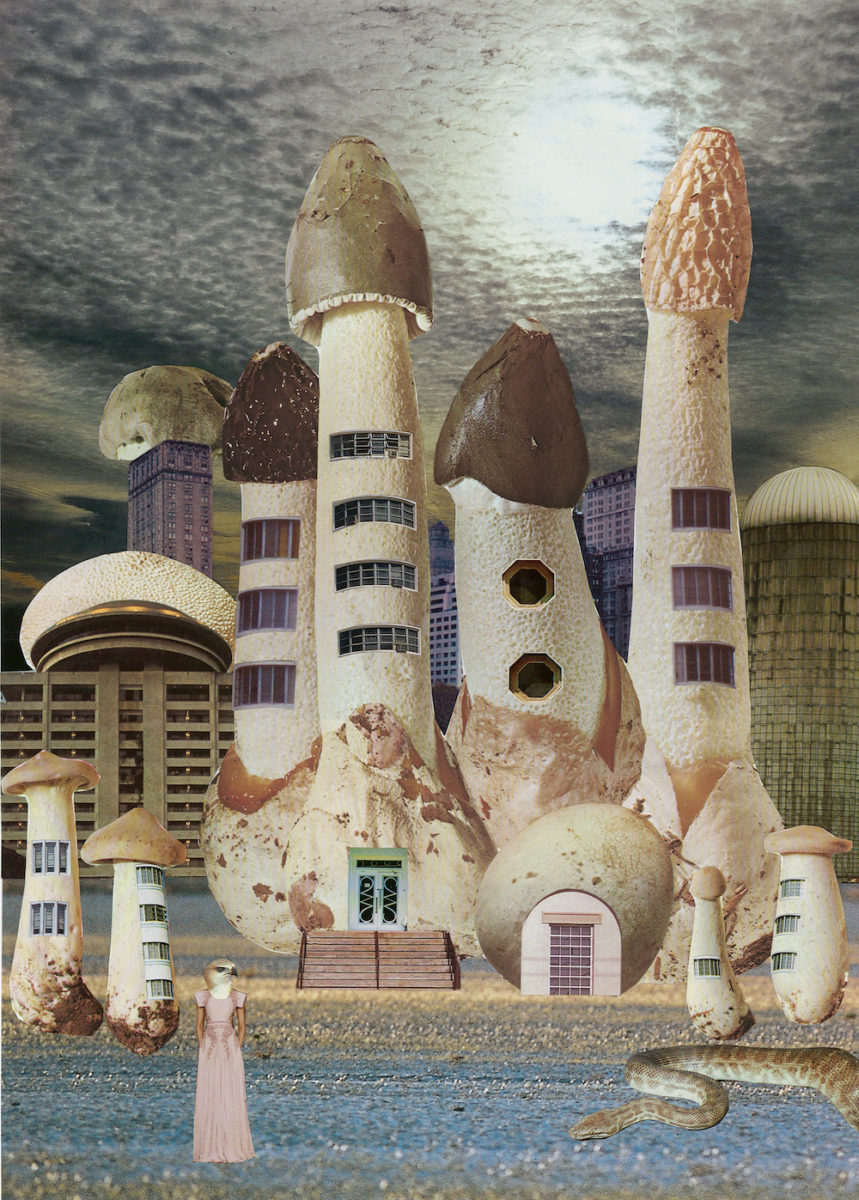

What Mushrooms: the Art Design & Future of Fungi, a new show at Somerset House, does well is offer a variety of visual explorations of mushrooms that buck that trend. As my father, who visited with me, pointed out, making mushrooms look contemporary is important if they’re really going to be integrated into modern culture and imagination. Works like Seana Gavin’s collages and Haroon Mirza’s delicate spore prints on copper, even Cy Twombly’s older, scratchy, loopy drawings, all evade kitsch. Others, like Graham Little’s aggressively sentimental painting and David Fenster’s absurdly serious costumed monologue, lean in so hard they come out the other side unscathed. But it remains a decidedly difficult task, making the artworks that achieve it all the more impressive.

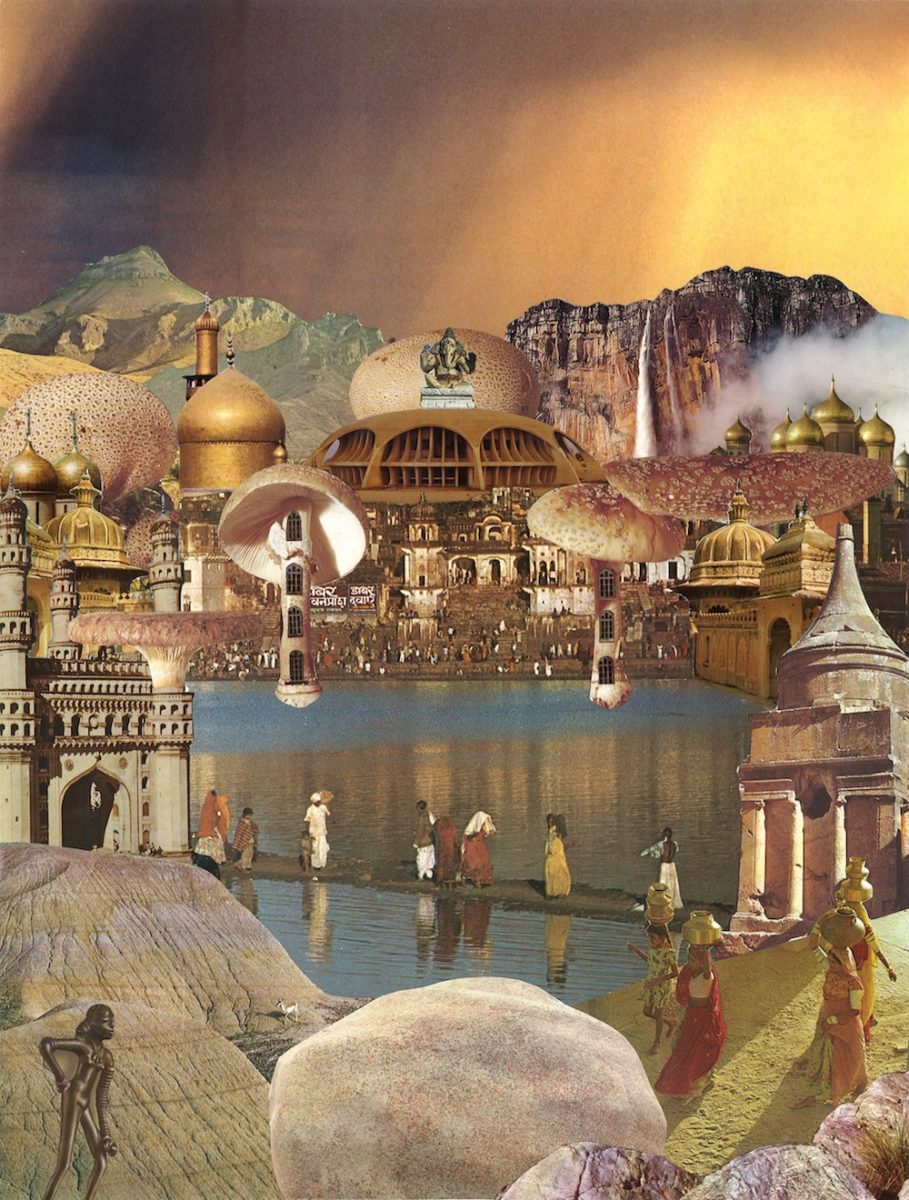

A lot of the most visually interesting work involving mushrooms is related to the “magic” varieties—artists have been drawn to psychedelics for a long time. Despite the fact that most of the more ambitiously fungi-centric theories of human consciousness, spirituality or the artistic impulse are, in academic terms, complete bunkum, there’s no doubt that these stories have themselves influenced generations of artists looking to locate themselves and their work in a primal narrative of “hallucinogenlightenment”. For many, mushrooms provide a plausibly ancient and mysterious yet safely inanimate alternative to a deity, or other ultimate source.

- Left: Grey mould (Botrytis cinerea) on strawberries; Right: Spore tubes on mushroom (unknown species). Both images courtesy Macroscopic Solutions, not included in Somerset House exhibition

Attending exhibitions with experts is always a strange experience. They already know a lot of the facts that amaze others, like that we share a single cell ancestor with mushrooms, or that you can make anything from floors to food to fabric from mycelium. There’s a lot of on-the-spot identification, and quibbling over whether Lois Long’s beautiful illustration of Coprinus comatus is missing a crucial identifier, or is just at a particular stage of decay. Comparative disregard for the seismic impact of John Cage’s work aside, experts are a treasure trove of interesting information.

According to Fődi for instance, people in Hungary have been making material from mushrooms for centuries, but it’s an orally transmitted tradition and is dying out slowly. At the Transylvania Mushroom Festival people display felted and embroidered mushroom sculptures as part of the spectacle. Mushrooms saturate different parts of the world with different intensity. Here in the UK our interest in mushrooms really only goes back to the nineteenth century and has been patchy since then, but in Qingyan there is an entire shrine to the man who developed shiitake cultivation, and in Castilla the six-thousand-year-old Selva Pascuala cave mural depicts what are almost certain to be mushrooms—if not definitively magical.

“Mushrooms provide a plausibly ancient and mysterious yet safely inanimate alternative to a deity”

Having an expert or two in your back pocket also helps put interest-spikes like this current one into perspective. Most of the mushroom people I know are delighted by the increasing visibility of fungi in the cultural sphere, but also sharply attuned to just how “surface” some of these representations are. As mushrooms become the miracle ingredient in everything from coffee to face cream to non-alcoholic “spirits”, it’s important we not forget that they are more than aesthetic objects, materials or a nexus of marketing hype. LA boutique brands selling minuscule quantities of extract and promising immortality; historical narratives which over-emphasise the importance of psilocybin; even eco leather alternatives for fashion houses are all just ways of using mushrooms as materials that slot happily into our current system of individualist consumption.

Fungi have a lot more to offer, as many of the artists, curators and intellectuals who engage with them point out. From the lessons we could learn from the symbiotic “wood wide web” and the not-plant-not-animal world of a thousand sexes, to the complexity vs simplicity debate in evolution, mushrooms can do more than give us new ways to repeat old patterns—they could prove to be extremely exciting critical tools.

- Seana Gavin, Mushroom City (left); Toadstool Citadel (right) © Seana Gavin

If we don’t keep one eye firmly on the science, ethnography, cultivation and history of mushrooms we’re in danger of burying their real significance and potential under an avalanche of wild claims, wishful projection and speculative history—all of which are fine and even necessary in art, but mushrooms aren’t just art. Despite appearances, it’s increasingly looking like there is no “just” about them. They’ve been here longer than us, and they may hold clues as to how we could stay here longer than we’re currently on track to. There’s promising research coming out around the use of fungi in environmental cleanup, treatments for Alzheimer’s, carbon capture, reforestation and much much more. If we do run out of time, Jae Rhim Lee’s burial suit reminds us that mushrooms will keep life going even after we’re dead. Fungi are the future—and it looks like their foot is firmly in the door.