When I was a teenager, I was obsessed with pornography. Not the PornHub or RedTube variety, but rather the naked flesh that I realized could be found in the most innocuous of places. I collected prostitute cards from phone boxes around London and stared up at the sticky top-shelf mags in the local newsagent. I photographed close-ups of breasts and crotches on billboards and shop windows, and memorized artist names to look up for my peers on the school computers. Terms like “sex” and “cock” were inevitably censored but images like Jeff Koons’s iconic Made in Heaven series, shot with his porn-star wife, were freely accessible. I was fascinated by the double-standards of acceptability around sex.

The first time I saw a John Currin painting, by then in my early-twenties, all of my adolescent confusion came flooding back. Here was an artist pushing titillation to its limit and beyond, conjuring a world in which imaginary women lounge and pose, or feast upon luscious fruits replete with symbolism. His canvases are like a hall of mirrors, depicting the simmering sexual repression of society—with all the humorous, grotesque and unsettling results of the classic fairground attraction. I was gripped.

“The Bra Shop is unashamedly, deliberately, horrifyingly bad taste—it is kitsch on steroids”

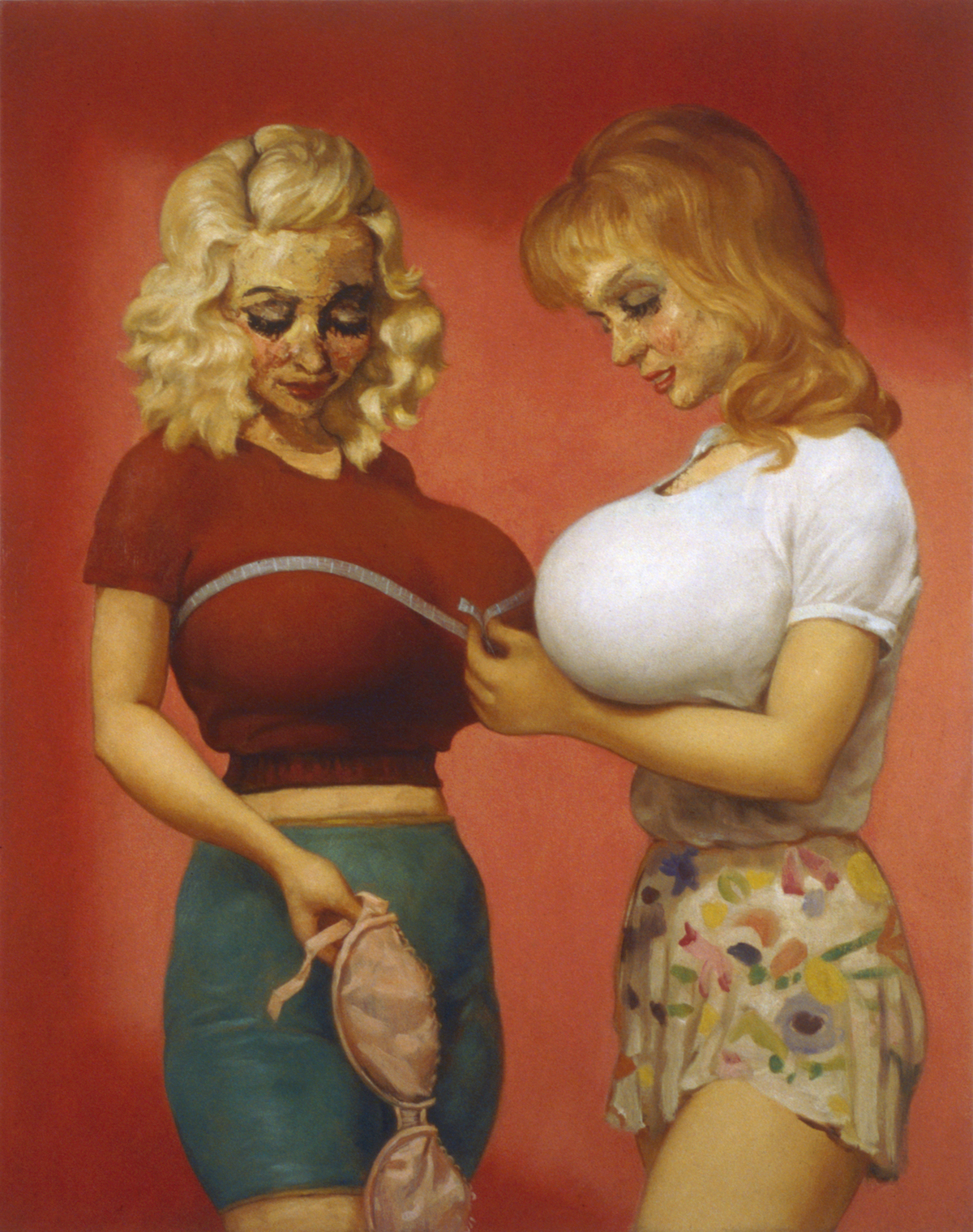

The art/porn debate is nothing new, but here I encountered a painter challenging more than a straightforward binary and offering up few easy answers. Currin’s paintings are an overt pastiche of styles, gliding glossily between the old masters and pure cartoon. The Bra Shop both exemplifies this slippery transition and stands apart from it; less self-evident than his earlier references to Cranach and Dürer, more absurdist than the delicate representations of 1970s porno magazines that came later. It is a painting that revels in a joyful vulgarity that is entirely its own, with a blonde and a redhead fixated by their own outsized proportions.

As John Waters once famously said, “To understand bad taste one must have very good taste.” The Bra Shop is unashamedly, deliberately, horrifyingly bad taste—it is kitsch on steroids. Enormous breasts are the inevitable focus of the painting, as two women ostensibly shop for new underwear. Heavy and impossibly spherical, their busts protrude in a manner worthy of iconic soft-porn director Russ Meyer, known for his fixation with phenomenally curvaceous women, who was behind such cult classics as Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, Supervixens and Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

Both Currin and Meyer vamp up female sexuality to the point of distortion. Their refusal to offer straightforward satisfaction returns the hungry gaze inwards, to self-reflection. As the two women in The Bra Shop look intently at themselves and one another, an allegory of looking at the painting itself is quietly insinuated.

“The image is so sexist that it’s sort of beyond repair, it was already ruined before I started it”

The pair’s faces are fiercely textured, with thickly clotted mascara and rough, mottled skin. Paint is pasted in layers that contrast the tonal flatness of their cartoon-like bodies, to strange and uneasy effect. Currin has described this process of layering, saying, “The palette knife reminds me of the way it feels when you ruin something with love. You can’t improve it, you can’t smooth it out—it only gets worse the more you touch it. The more love you show, the more you destroy it.”

Unlike many of the characters in his other paintings, these women’s faces do not subscribe to flawless, all-American cosmetic ideals. Instead, they are depicted at a point of disintegration, and draw attention to the materiality of the work as a painted surface—they are a fantasy, an illusion and a fiction. This might be a twisted reflection of life, but the closest element to reality is the viewer themselves.

“I had already received a small amount of criticism about my sexism, and I wanted to make something that I wouldn’t have to worry about being termed sexist—because the image is so sexist that it’s sort of beyond repair, it was already ruined before I started it,” Currin also explained, extending his use of the palette knife as a metaphor for the image itself. It is a fitting comparison, with the many layers adding up to something more than pure parody.

It is difficult not to feel complicit with the act of looking, as if you ought to be ashamed of yourself for appraising these women’s assets. To look is nonetheless to enter into a different dimension, where normality is thrown out of the window and replaced instead with an exaggerated view of the world where there is no room for hidden hypocrisies. The Bra Shop demonstrates without doubt that, like the historic male-female abuses of power unveiled in the #MeToo age, it is beyond repair.