London – When Jonah Pontzer would travel to art shows, like a hunter looking for big game for his popstar clients, he noticed a recurring motif: the Hermès Kelly Bag. “You always see the same kind of woman carrying this thing that clearly makes her feel or look so unique,” he remembered. “But every other woman at these fairs has one too.”

Jonah Pontzer, a 34-year-old American artist, whose show “Fresh Hell” closes this Saturday with a performance piece “Apology Tour” at Rose Easton Gallery, describes himself as “a former professional best friend,” someone you could take anywhere. He has a bright, inviting face, ever supported by the hint of surgical augmentations. I met him at his home in Primrose Hill, where we sat for an hour on the floor as he and I sipped on tea and Diet Coke, respectively. Afterwards, we spoke for hours at a local Italian restaurant, where he flirted with the waitress and would greet passersby from the local British high society. An older woman with an iconic hairdo would pass by, slow, reserved, “She is a legendary fashion writer (Suzy Menkes).” An older man in a perfectly tailored suit gave him a smile. “That guy is the wealthiest person in this neighbourhood; he always goes into that grocery store right before they close to see if he can get free flowers. Everyone loves a deal.”

He has a fast, audacious, and witty opinion on almost anything that he has even the slightest understanding of and will frequently make statements that sum up everything beautiful and tragic about any situation. He has a fairly deep understanding of theoretical physics. He had a wealth of war stories from his involvement in the Western art scene from the aughts and early 2010s. It’s what led him to not only the creation of art as a business but also to the collecting of it in the first place. After working as an artist and fashion illustrator for years and a brief stint as artist-in-residence for mega consultancy McKinsey, he suddenly had some of the biggest names in the world of pop music and beyond texting him on WhatsApp asking for his insights, connections, and advice on the best artworks to acquire. But after spending so much time around such people in such high-end places, he began to feel like a Kelly Bag himself. “I became an accessory. They’d wear me out — literally.”

“Eventually, his practice would revolve around this work. When he would become overwhelmed with his killing, he would retreat.”

So when the gallerist Rose Easton asked Jonah to create work for a show this past January titled On the Edge of Fashion, Jonah was stood in the National Gallery in front of a favourite Vuillard painting, Place Vintimille, when he told her he would make a paravent — a room-dividing screen in five panels. “I was thinking about home, about the recent loss of my family home, about feeling lost and not having a home,” he told me. “It’s sort of about like, you know, estrangement from family, from the familiar and the once-seemingly secure. Suddenly, all these things exist only on a screen or in the few physical photographs I have, in the Google searches I can make, and the pieces I can puzzle back together to help it all make sense. I took images and made this painting into an object to literally divide rooms, to conceal and hide behind. Maybe because I spent a good amount of my own childhood in those familial rooms hiding, and it gives the metaphor something physical, beyond a pictorial plane.”

“In painting, I’m really into prisms and refracted light particularly,” he told me. “During the Renaissance, ‘cangiante’ color-moding was always about the divine and the presence of God or whatever. So I just thought, let’s go for it. In a nod to not only his estrangement from family but his feelings of being a mere accessory to rich-girl clients, Pontzer created his largest work on paper to date, “Cancer Son Greets the Day, Dresses Accordingly,” which rips a Nat Geo Arc image of a dressing spider crab, superimposed over a rain-streaked window view of the artist’s coastal Norfolk garden at sunrise, all painstakingly rendered in colour pencil, ink, watercolour, marker, and covered in an acrylic layer of simulated Hermes crocodile skin, with refracted light painted in final passes of interference oil colour.

It’s an object with two faces, as when you approach the work in the gallery, you can see the image crystal clear. But up close, it becomes skin, the image disappears, and it’s all texture. You’re interacting with something completely different. It’s not just the fact that it’s an object or surface. “It occurred as an amalgam of a bunch of shit that I was really concerned with and probably depressed by at the time,” says Jonah.

Pontzer was born in Ridgway, Pennsylvania, a small town in the rural Allegheny mountains of Elk County, to two attorneys working then in family practice law and real estate, respectively. The nearest major metropolitan area was Pittsburgh. His queerness was recognised early by both the artist himself and nearly everyone else in his small town. “It wasn’t a particularly safe or happy environment for me,” says Jonah “I was confronted with slurs and bullying regularly.”

When he was in the sixth grade, he got in contact with the dean of admissions at the prestigious Georgetown Preparatory School (America’s oldest and only Jesuit Catholic boarding school for boys), attended by generations of DC elites such as Supreme Court Justices Neil Gorsuch and Bret Kavanaugh, and by international students from every corner of the globe. Pontzer’s father had attended the same school in the 1960s, and after discussions with the dean, he was promised that if he got his way down to DC, they would give him a scholarship that would help him become independent and set him on his future path.

Here, he was taken under the wing of a teacher who would regularly take Pontzer to see art at the various museums dotting the National Mall. He developed an early love for Old Masters — Raphael’s ‘Alba Madonna” — and modern AbEx giants such as Barnett Newman (“Stations of the Cross”) and any and everything Les Nabis (Vuillard, Bonnard, Vallotton, Serusier et al.). His time in DC offered him a certain freedom and understanding of himself beyond the confines of small-town America.

“My relationship to art… it’s just a day-to-day thing,” he explained. “I like talking to people, but I like looking at things. I’m a really good thief. I mostly collect people’s paintings so I can, like, rip them off; I like to study first-hand and discover how they’re put together. There is no better practical education.”

From a young age, his family noted and encouraged his deep love and skill for drawing and mark-making. In an otherwise preppy environment, Pontzer became known among his peers at Prep for his affinity with creativity, which would come back to benefit him in his work collecting art for the glitterati and hedge-funders, both in his confidence among the elite and with the connections it afforded him. His days spent visiting the National Galleries and public collections helped him develop a heightened understanding of canonically significant works.

He gained admittance early to Central Saint Martins in London for performance design and moved to London at seventeen. He quickly realised he had little interest in performance design, “I thought it was the most useless thing,” he quipped, but it helped him develop a sense for his curatorial and theatrical taste, which he would synthesise after a lifetime of discovering art on his own. To pay his university fees, Pontzer found work illustrating for the European fashion houses before the advent of iPads and technology killed the game.

Pontzer would travel back and forth to Paris for this work to stay afloat—the 2008 financial crash was in the air, and he desperately needed to support himself while living in London and pay for college—he quickly attained the worst attendance record at CSM since the ’70s and developed an unstable relationship with the institution, which he paid international fees for on his own.

In his final year at CSM, he was seeing an older man who was pursuing a baby and a family, which Pontzer wanted nothing to do with and attempted to break it off, though the boyfriend wouldn’t let him go. After dodging his calls, Pontzer finally told him that he was moving on and wanted to be left alone. The boyfriend informed him that he had contracted HIV, which Pontzer would then discover he had as well. “I just felt that drop, you know,” he said, “like black ink into water.” After having grown up in such a homophobic small-town environment, all he heard of queer people was that they got AIDS and died, so he almost expected that one day it would happen to him.

Pontzer’s diagnosis forced him to stay in the UK as he couldn’t afford the medication back in the States and closed out CSM with extreme illness and near-total disregard from his course leader and the administration. “In those days, antiretrovirals weren’t prescribed immediately, and after a few months, I got really, really sick,” he remembered. “My adoptive godmother, the artist Zoe Grace, was looking after me. A bunch of friends in the neighbourhood were looking after me. And on Valentine’s Day of that year, I said, ‘I need to take the pill. I need to be non-transmissible.’ At the time, it was still an extremely taboo subject. Lovers would cut you off. You couldn’t use Grindr or the apps without being immediately blocked. “It was shit. It was awful,” he recounted.” But it gave me something to work with, and it gave me something to make work about.”

He returned to the US after graduating to secure a visa to remain in the UK. Here, he saw his parents for the first time in some years and chose not to tell them about his HIV status. He felt trapped and without many remaining options.

One night, on this American stop-gap, he spilt a drink on a handsome British doctor at a bar on the Southside of Pittsburgh, whom Pontzer believed was faking his accent, and a week after they met, they were engaged, now married for ten years. The doctor assured him that they would figure it out; he just wanted him to remain in the UK.

Pontzer returned to the UK, and though his immigration status was secured, he was inundated with anxiety over his fledgling, post-university career prospects. He applied for a SEED grant through CSM to build an art practice, which he was denied, owing to his trouble with attendance and the apparent reservation from supporting him after his diagnosis.

“During another such period of isolation, he would lie in bed and take photos of his window, observing the changes in the refraction of light.”

He spent a lot of this time alone, creating work in his East End studio, spiralling in and out of depression. Through the help of his husband, Pontzer saw psychiatric care to deal with the complexities of his life experience to this point. After finding a doctor and seeing him for some months, the psychiatrist sent Jonah something unexpected: an autism questionnaire. “I got stoned one night,” he giggled, “I maybe get stoned every night, but anyway, I read it through this kind of clean haze of, you know, self-empathy, which I don’t otherwise have. I’m normally really mad and horrible with myself. But it was just like reading about my life with total clarity. I was like, ‘Holy shit.'” Everything that had hurt, everything that felt so uncomfortable in his interactions with others, all the harmful relationships he had, the attachments he formed with people, both good and bad, suddenly made sense. “Autism gave me a real sense of self. It provided a road map. And I probably never had one before that. I suddenly knew where I was and could see where I was headed. “

He started taking whatever work he could get his hands on, and eventually, he was approached to work for the global consultancy firm McKinsey through a program called London Art Studies, “a wealthy women’s group for learning about art.” Pontzer would meet with McKinsey’s heads to create art with them in an exercise meant to foster team-building amongst the partners, an artwork that would join their collection. The money from this work would allow him to develop and support his own practice beyond the residency.

“It was a weird sort of art therapy,” he said of the experience. He was dealing with the same sort of people he had come to know in boarding school, just grown up. “I was hearing conversations I shouldn’t have heard. I was sort of listening to how they propagandise.” His interest in economics and familiarity with high power fueled his interest in the work and fostered his connections. “I came out of that experience having made an artwork that was fucking horrible because they all made it. But I didn’t care, and neither did they. We had fun. Working closely with the heads of McKinsey, whose power he recognised didn’t understand until the experience progressed, made him skilled in turning outside ideation into work. I learned I could use innate creative senses to distil and empower the partners’ ideas through a shared sort of synaptic pressure as it relates to current events or world economies or anything they were working on.”

School was over. The stint at McKinsey was coming to an end… and he needed New.

“I started looking at everybody else’s work. I am fortunate to have a job that allows me to support my peers and collect a lot of my friends’ work and stuff when I can,” he looked around his studio. “Everything in here is mostly someone else’s. But that’s the nature of making and the nature of the game I started to play for myself as an adult with bills — I had to build a community to engage with art meaningfully and to grow as an artist myself.”

Instead of institutional training, he continued his earlier studies of other artists’ works to aid his understanding, hone his tastes, and develop his personal sense of style. “Like I said, trying to pass as something my whole life, having to mask to survive, I guess I’m a really good thief. His own practice became a daily observance of art, visiting museums like he had while he was in high school and trying to emulate other artists’ work to attain technical mastery. “And it made me very excited. I love the idea of forgery. Everything today began as something else, and no idea is truly OG, but when well researched and assembled, something new, personal, and magical emerges.”

He attained, in late 2018, a residency with Sarabande: The Lee Alexander McQueen Foundation, where he developed work that comprised screengrabs of homoerotic and often pornographic content that he would recreate with deep precision, encompassing the hyper-surrealism of his own lived experience in the UK and in a serodiscordant couple. He turned to content from the AIDS crisis era as a medium to draw from, internalising the danger the filmmakers subjected the actors to with the insistence of unsafe sex, which led to the deaths of the stars at the height of the crisis. “When I contracted the virus, there weren’t a lot of helpful resources about contemporary experience… so I looked to historical ones.”

In early 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic forced him to move to rural Norfolk, where his husband practices medicine. “Once again, feeling trapped in a small town was in many ways just as surreal as the pandemic itself.” Many of Pontzer’s friends were losing their homes and living out of their studios. Many lost any roof at all. About a year into the pandemic, Pontzer’s friend and longtime collaborator Emma Witter introduced him to someone who had access to a slick Mayfair penthouse office in an abandoned finance firm and asked them if they could make use of the space to help the local council.

Pontzer called up artist friends and asked if they could make work within a week for a show, one of the first exhibitions to come out of the pandemic in London, titled Triggered Economics or How to Commit to the Inevitable, to which the artists contributed either site-specific work or older catalogue work. The foundation of the show came about with Pontzer and Witter ruminating over the hardships the pandemic created for themselves and their community. “They gave us the nicest office in Mayfair,” he explained. “I was like, ‘That’s fucked up because people think I’m a princess as it is. People think I’m a socialite. People hear whispers about who I might know or work with, and so I just leant in.” He embraced it as a means to aiding his community and securing it.

The show was a success, but more importantly, Pontzer and Whitter quietly filled hundreds of empty office spaces in the glamorous district with artists who had been forced from their own spaces- without charging the artists themselves. Many occupied the spaces for over a year, with the last occupants moving out in the early summer of 2023. “It was basically about that studio initiative,” he explained. “Everybody losing their homes, everybody being shut down for two years, all these really weird and terrible things. And we took the disused offices as the surreal opportunity it was and played with it.”

Ironically, while using the penthouse (at one time, the most expensive private lease in the capital), Pontzer was kicked out of his own London home and found refuge between staying with his husband in Norfolk and house-sitting for friends. He fell into a bout of depression and spent his days drawing the TV screen. It was at this time that he began to fall deeper into a world he had lightly played within the previous few years: art collection and advisory. Through his connections from boarding school, CSM, McKinsey, and beyond, he was approached, at first informally and in time with more intensity, to poach works at art fairs for wealthy clients. “I made it really easy,” he explained. “I could make it fun.”

Over time, he attracted an international reputation for identifying the best of historical and contemporary art. The biggest pop stars in the world, hidden behind red tape, would solicit his advice (I later fact-checked the clients Jonah named off the record, and he has receipts and identification from some of the most popular musicians and movie stars in the world). Most of the time, they wouldn’t even know that Pontzer was himself an artist. Rather, he was like a secret weapon in a big game hunting ground. “I could do it on the phone, and my friend Adrian would shuttle me around in an S-Class for clients in town wanting the JP experience. I could shoot text off to people on set on the other side of the world and close a deal. It’s surreal, but that ‘job’ makes me feel really bad,” he laments. “It makes me feel like a cannibal.” His own love for public art and his guilt as an artist himself, hiding behind the glamour and money of high society, filled him with dread and the understanding that some of his clients would buy art for tax purposes and store the works in freeports waiting for its value to skyrocket. “I felt like I was sending paintings to their deaths”, says Jonah, “and I would just walk through art fairs like, ‘Well, I killed that fucking one and that one too. That won’t see the light of day or too many viewers’ faces for years.”

Eventually, his practice would revolve around this work, his studio and production bills covered by it, and his own painting bolstered by the deep material research it provided. “I am lucky to get to handle the works I do — to see, hold, study them first hand. It’s a privilege I don’t take for granted.” When he would become overwhelmed with his killing, he would retreat. He would draw the TV screen copy meticulously by hand photographs he’d make of his own world. He would expose himself and the pain of being used by his clients in his work and, in turn, his use of art and other artists to secure his life and practice. He’d lean in. He would become the Kelly Bag.

His practice is transparently masochistic. While Pontzer has made a career out of exposing and extolling other artists, going out of his way to find ways to support his friends and other artists in need, he has never offered himself the same financial or structural support. “I didn’t really know how. My self-esteem is pretty low despite my masking efforts.” The cycles of self-abuse bled into his own work. Ending the cycle was impossible as he needed the money to support the work, and the work would feed off the pain of needing the money.

“I’ve helped a bunch of other artists,” he explained. “I know the formulas for those things. I’m not particularly interested in doing it for myself… I’m not sure one can, but I tricked myself, and this year, I said, ‘Just make this work. You can do all of these things at once. Just make this work.”

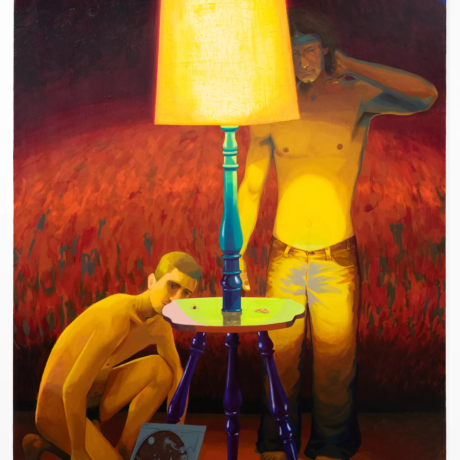

So after the success of his first show with Rose Easton in 2023, where he featured the screen painting with its crocodile surface, the gallerist approached Pontzer to put on another show, where he offers an exhibition of transom windows. Up now through September 16th, “Fresh Hell” is an exploration of isolation, the artist’s observance of the changing light observed through window, an exploration of his periods of isolation and fixation on the predatory nature of art collecting and all its social and economic politics. “All of that fire and all the bullshit and all the horrible things that were happening and, you know, the cataclysmic depression that I was facing and really shitty financial situations, they just bled their way into the drawings, and I started to paint on top of them.”

It’s a wonder-making out of the mundanity, the overwhelming nature of letting a problem persist and finding beauty in passivity. He created a series of six paintings, framed in identical, working transom window frames, some mounted to a wall, two straddling an open doorway as free-standing sculptures. “I realised that the dialogue the paintings had with their objective nature and the space of the gallery was maybe the best thing that’s happened in a long time for me,” says Jonah.

Pontzer found himself observing people’s reactions to the work at the opening and found interest in certain onlookers’ dismissal of the work. “I don’t know if people were seeing them as drawings, as paintings, as sculpture…or what…” They’re all three, btw. It made him consider the changing art world. His work is an amalgam of others, what he has used for himself, and he wondered how social media may be changing what people are interested in. “You have to be so prepared when your works are out in the world doing their own thing for nothing to happen or to change,” he explained. “You can meet yourself at that event horizon, preparing to be torn apart or swept away or taken somewhere else, and maybe you just spend a lifetime drifting over that edge, waiting for something to happen but … just being slowly torn apart. You just have to be really comfortable with nothing working and for life to remain unchanged despite the work providing or not providing opportunity. Doors may open, but they don’t always lead somewhere. The weirdest thing is, if you go to sleep every day, if nothing’s wrong with you, you wake up and no matter how bad things are, and this is the thing I have to tell myself, but if you don’t harm yourself, you wake up tomorrow. We all have to find ways of continuing.”

His work, in essence, is a reflection on cycles, memories you have, and you’re not sure where they’ve come from. It’s wrestling with making real something that only exists in an attachment to tragedy. Its form depends on the need for reflection. “I want to discuss trauma,” he stopped himself, “I hate that term — everyone uses it and like, who fucking cares?” He continued, “You’re applying colour to abusive situations. You’re saturating things. I just thought, ‘You gotta get really comfortable being by yourself, probably alone, afraid to go outside most of the time, so what really works for you? What allows the sleeping through the night… what makes the waking up less heavy?”

He then related it to particle theories in new physics, how something exists both in the perception of the particle and its real existence, its counterpart somewhere else in the universe, and how he’s moving between those existences with his two faces in art. “In my work, in both jobs, any number of people are worried about what I might say about them, do to them, and maybe I’m worried about the same, and vice versa,” he admitted. “And I’m watching that touch some people in my life, and it’s gratifying and horrifying. And that experience of it is totally for mine.” He lambasted artists who contrive, noting that they only make their work for themselves. “Everybody wants to be loved, and everybody needs attention to some degree. But no, you don’t. In some fucked up way, the in-jokes in these works are only my jokes. And like, in a really wanky way, I was like, ‘Whoa, I made that. I made that. I was coping. I made that for me.”

He slowed and returned to my first question, the only question I had asked him at this point, which he had been answering for the last hour: What is your relationship with art? “It occurs to me like the weather. I have to get up and dress for it appropriately every day.”

Written by Saam Niami. All images courtesy of the artist and Rose Easton Gallery. Photography by Theo Christelis.