It is entirely possible that if you visit the banks of the Dead Sea later this year you will see a very small boat, made of magnesium, carrying Simon Starling from one side to the other. That is, if the local authorities don’t take umbrage at his plans. Although the boat is already in existence—displayed at Nottingham Contemporary in the English Midlands under the title Project for a Crossing until mid-June—the paperwork isn’t exactly in order yet. Still, the boat is made, the proposition has been laid down.

“I have my brother-in-law to blame for that,” the artist tells me as we meet at his quiet Copenhagen studio a month before his largest UK exhibition to date, which is being mounted as part of The Grand Tour. “He’s a bit of a bike nut and he owns a frame that was made in the early 1980s out of magnesium from sea water. I thought: if you can make a bicycle, why not a boat? I looked at where the concentrations of magnesium are the highest and of course the Dead Sea came up, which has an extraordinary 45 grams per litre of water.”

Et voilà. This serendipitous happening upon projects seems to be a running theme for Starling who, despite the precise processes behind much of his work, claims that many of his projects come to him with little pre-planning. “There’s no real system for it. There is this idea that I’m carrying around a ton of sketches for things in my head and suddenly one finds a home. The practice has its own momentum and I’m just there to keep it on track. The classic example of that is Shedboatshed (Mobile Architecture No. 2) which I made in Basel, when I found this wooden shed with a paddle on the side. In a few seconds that whole project fell into place. Then it’s just about being belligerent enough—and lucky enough—to make it happen. The curator called the owners and they said: ‘Oh great, we were looking to get rid of that thing!’ Another gift falls into my lap. It’s a nice feeling that it has its own life.”

“What I’m doing in a gallery situation is presenting a journey that I’ve been on, a process I’ve undertaken”

Similarly, the conclusion doesn’t always seem to be dictated ahead of time. Project for a Crossing—displayed at Nottingham Contemporary alongside another boat-led piece, 1997’s Blue Boat Black—may, or may not, actually transpire in the manner initially envisaged. “Negotiating the situation in Israel is interesting to do these days,” he says in a somewhat gleeful manner—he certainly enjoys the challenge. “There is a very wonderful French curator called Ami Barak who lived in Israel for many years and he’s been a huge help in connecting me with the right people. Everything is done on a bit of a shoestring. You find your way and hope for the best.”

I’m guessing that as an artist, indeed, a Turner Prize-winning artist, Starling manages to get the rules bent for him a little further than they might typically be. “Oh totally, you get away with murder! People are generally very supportive and excited wherever you come across them, I don’t know about the Israeli military but we’ll see. I like this idea that the project will exist as a proposition, as a projection of something that might or might not be.”

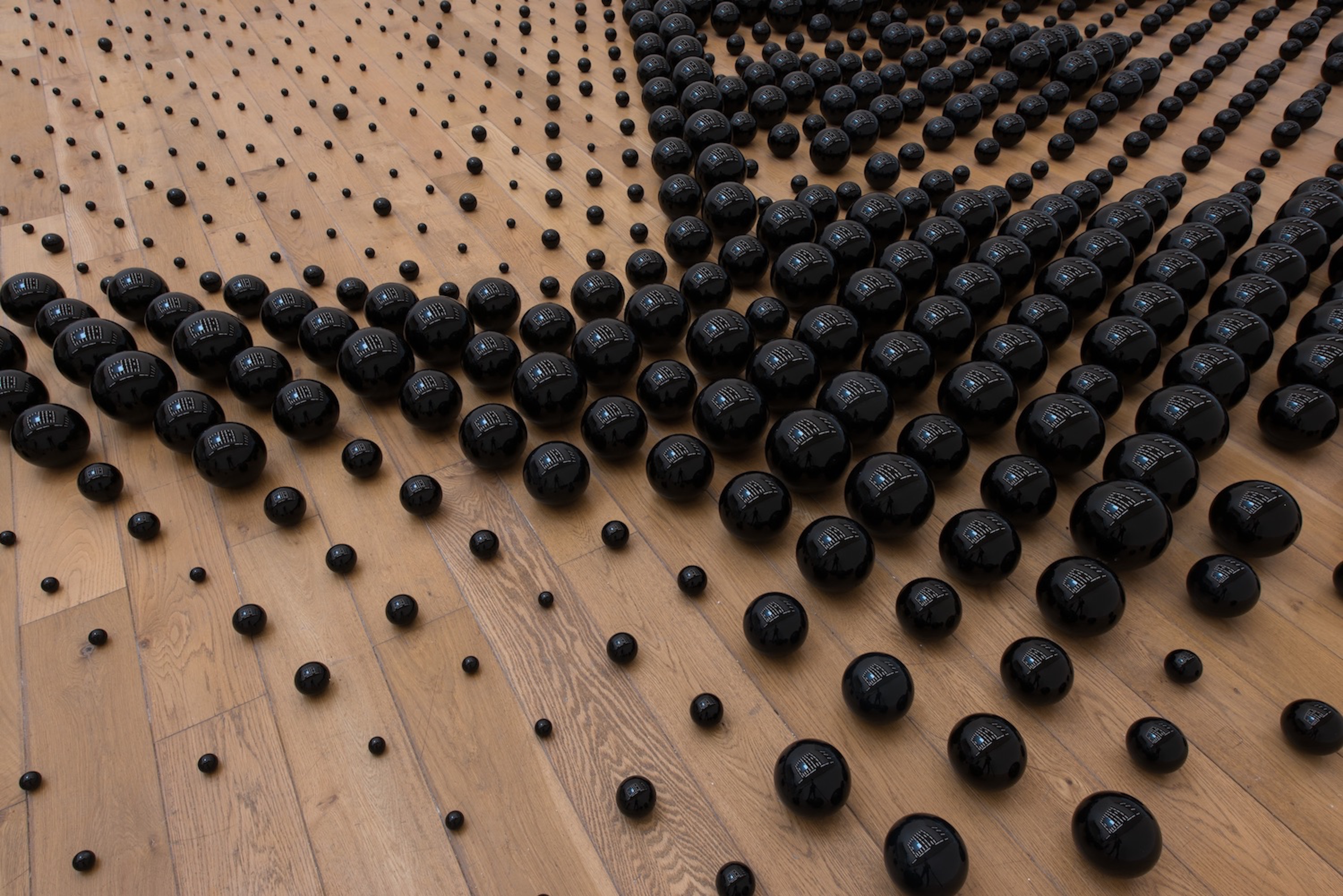

Starling has become recognizable for these circular, weaving narratives that more often than not aren’t deemed complete within a specific object, exhibition or physical place. It seemed fitting to speak with the artist before seeing his show, where the temptation to place the be-all and end-all on the objects—which are always spectacularly produced, from the high-shine Nanjing Particlesto the stunning La Source, a meticulous arrangement of glass spheres which recreates a small section of a photograph when viewed from above—may trump the importance of the journey itself. “I’ve always liked the idea that the work is a rather expanded realm in a way that consists of one-on-one experiences with objects and galleries, but also consists of books, anecdotes and texts,” he tells me. “It’s a complex thing but I try to leave that exploded space for people to navigate.”

This has, from time to time, formed the basis of a criticism of the artist’s practice—that complete access to the work isn’t possible for the viewer, Starling himself being the only one who holds the full deck of cards. As he concedes, “It is almost a way of holding onto the work for me. But what I’m doing in a gallery situation is presenting a journey that I’ve been on, a process I’ve undertaken, and I’m asking for people to look at that in reverse. The circularity of many of the projects is a device to tell a story and it means that if you’re making a work about process, if you start and end in the same place, then somehow the journey becomes the important thing.”

“It’s not really in my nature to put myself front and centre in the work”

His practice being what it is—technical, specialist—he regularly works with makers from outside the world of visual art. I wonder if it can feel difficult to let others in. Actually, he says, “That’s been a really nice part of the journey, to establish long-term relationships with very skilled people, with foundries, or mask makers: specialists. When I started making work in the early ’90s I had this idea that everything had to be done by me. It was about what was possible for one person. It was about a resourcefulness. Slowly I realized that what I was doing was making work about making. Now I’m generally aware of what is possible beforehand but, for example with Yasuo Miichi, the mask maker in Osaka, I made designs for this series of masks which are quite specific, but Japanese Noh mask making is a very ancient craft and very rigorous. Those masks are really a meeting of my ideas and his craft skills and aesthetic language, which is so refined and meaningful on so many different levels.”

Starling’s work often fuses traditional and modern techniques into one larger process. The Nanjing Particles (2008) occurs in the gallery space as two large stainless-steel sculptures and an inkjet print. It finds its way to this point via 2D images of two silver particles—taken from a pair of 1875 stereoscopic photographs of a group of Chinese migrant workers—that were created with the aid of a one-million-volt-electron microscope. These images were then scanned and translated into computer renderings from which the two final sculptures were formed. In this journey, cutting-edge meets nineteenth century.

- Left: The Nanjing Particles, 2008. Courtesy the artist, Mass Moca, North Adams and the private collection Jacques Sequin, Switzerland. Photo: Arthur Evans; Right: Red, Green, Blue, Loom Music, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Franco Noero. Photo by Sebastiano Pellion di Persano

“A lot of what I’m trying to do in using these traditional crafts is to understand my own relationship to the technology that surrounds me today. The idea of using anachronistic things somehow gives space to reflect on the relationship that we have with modern technologies. Everything is a hybrid in a way, and in the work there is this constant flicking backwards and forwards between data and matter, digital and analogue.”

Starling’s penchant for process seems to have been piqued in childhood, with his “DIY demon” father. “He refused to pay anyone to do anything. There were a lot of possibilities at home to make things: go-karts, guitars. I got hooked into it. I built a darkroom when I was 11. The magic of making a photograph stuck with me. The photography course that I studied in Nottingham was very thorough as a way to learn the basics. On the first day they gave us a cardboard box and taught us how to make a camera. It was a very pragmatic approach.”

These early years offer an explanation for his work now which can be both rigorously technical and quaintly homemade, and which sets him apart from his contemporaries, the YBAs—whom it has been suggested he moved to Glasgow to get away from. “I’ve never been terribly interested in that very confessional, cathartic operation,” he tells me when I ask about coming of artistic age with the YBA set. “It’s not really in my nature to put myself front and centre in the work. A lot of that work is really great but it’s not my way.”

However, in 2005 he won that great YBA booty, the Turner Prize, for the aforementioned Shedboatshed. I ask if he feels it changed things for him, as an artist who seems to actively avoid the spotlight—following his move to Glasgow he relocated to Copenhagen to be with his family. “I don’t think so,” he says with a chuckle. “When anybody asks me that question I always say that I have a much bigger audience for my work, and that’s great. If I go anywhere in the world for an exhibition or a lecture now, people turn up! But it was quite tough to go through. It was great to win but you work for it. My God, they really put you through the mill. Dealing with the press is quite an education… I think it was the Daily Mail—I loved it actually—who sent a journalist to B&Q to buy a garden shed, and he tried to build a boat out of the shed, which of course sank.”

“They were taking the piss,” he clarifies, but he does seem genuinely amused by this clumsy reimagining of his work. A much-less discussed aspect of his practice, aside from the influences of technical process and complex narrative, is that it can be rather funny. This side definitely comes to the fore when the work is described directly by the artist; there seems to be a joviality to many of his ideas, a whimsical what if. “I often think about cartoons as being an ongoing inspiration for a lot of things. Tom and Jerry, basically. The crazy ingenuity of the ‘anything is possible’ philosophy of those destructive but creative cartoons. There is a lot of that in what I do, and Buster Keaton.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 27

BUY ISSUE 27