JR has never been particularly worried about the legality of his work. Like most artists who began their career on the graffiti scene, he has always approached the idea of authoritarian permission with fairly casual regard, relying instead on the assurances of the local community and the understanding that most of his ventures are likely to go unchecked or even receive retroactive consent. This self-actualizing freedom has allowed him to create monumental paste-up portraits throughout the world, shining a light on marginalized communities, celebrating unsung heroes and producing poignant political commentary, in places as disparate as Rio de Janeiro, Switzerland and Israel.

That being said, JR understands the importance of maintaining a level of anonymity in order to carry on working, hence the abbreviated moniker and a steadfast devotion to wearing a hat and sunglasses. His disguise is firmly in place when I meet him at Lazinc’s recently opened Mayfair gallery, which is dutifully covered in scaffolding to support a cut-out of an enormous pair of legs protruding from the second-floor windows. From the other side of the street, these limbs seem to correspond with a disembodied torso erected inside, and so the illusion of a man backflipping into the gallery is complete.

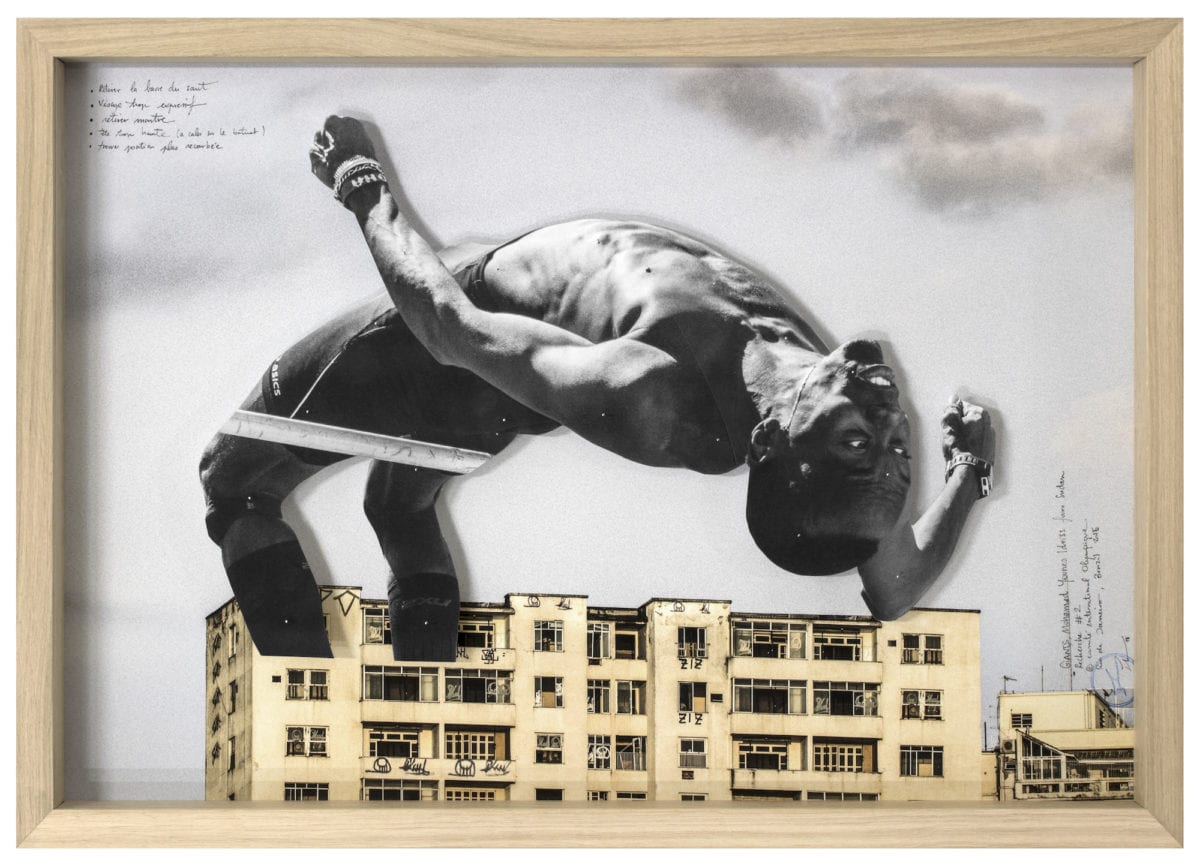

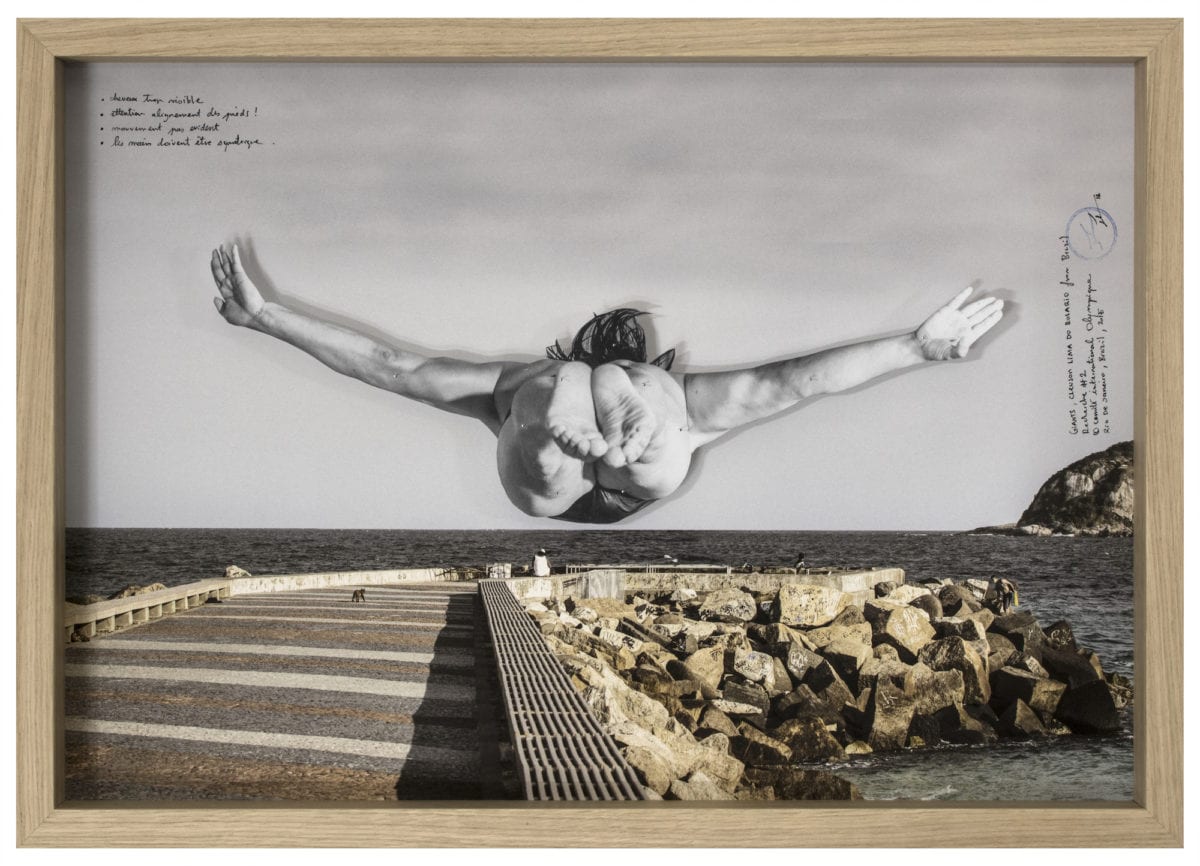

This site-specific installation is part of The Giants, an exhibition chronicling JR’s 2016 Rio Olympic Games commission. This hugely ambitious project presented gargantuan images of athletes jumping and diving, as if the city was their training ground. “They performed for the buildings,” he explains, as we tour his display of mock-ups, technical drawings and other collateral works. He is referring to the fact that each athlete posed for a specific building, creating a real synergy between the structures and their movement. “I have played with architecture before by pasting on walls, but suddenly I played with the city. I had someone jumping over it.”

This government-sanctioned project was by no means the artist’s first Rio intervention. In 2008 the Morro da Providência favela became one of the sites for his global Women Are Heroes series, where he plastered buildings with images of local women’s faces so that they appeared to stare out across the city. Photographs of the hillside gained international coverage, drawing attention to an urban area that many affluent Brazilians would rather ignore. The process of enacting the project was fairly lawless even by JR’s standards, as local drug gangs control the area. He gained an audience with the leaders, explained his aims and was eventually granted access to paste throughout the community.

It was the beginning of an ongoing dialogue, and the artist has since founded Casa Amarela, a cultural and education centre designed to support the favela’s youth. The latest addition is an enormous moon, elevated high above the property, with a reading room inside. The structure is so tall that a light was fitted to warn air traffic, “because we didn’t tell the authorities,” he adds, with a knowing grin.

- Mohamed Younes Idriss from Sudan, Recherche #2, 2017

- Cleuson Lima Do Rosario from Brazil, Recherche #2, 2017

This permanent intervention is perhaps the most pointed example of JR’s investment into the communities he chooses to work in. Its permanence is a departure from his standard practice and has helped to foster new relationships within the local population, as well as with the various artists who have been invited to teach and collaborate on site. It also serves as a stark reminder that cultural outlets are almost non-existent in many of the areas that JR visits, which is why he is always keen to offer mementos so that the participants can have some ownership of the experience after the paste-ups are gone: “I always do books that I give to the community, that aren’t available to buy. I took a couple to the drug dealers, and the head of the gang said “Where is that?” and I replied “What do you mean? It’s here!” Now he was born on the hill and knew it by heart, but I realized that he only knew it from the inside, because he doesn’t leave, so he had never seen this viewpoint.”

Collaboration is central to JR’s practice and manifests itself in the most basic sense that his photographs are reliant on the subjects’ willingness to pose. This interaction allows the artist a certain peace of mind, as it is clear that he isn’t imposing his work on the residents. “It’s a referendum. If everyone says ‘yes’ why should a man sitting in an office stop it happening? That’s why I do a lot of my work illegally. The Inside Out project has proved so much. People will make the work without me, I have nothing to do with it.” For this particular venture JR invited the public to shoot their own portraits (or visit one of the numerous photo trucks that were sent all over the world) and email them to the artist, who enlarged them, converted them to black and white, and sent them back. It was up to the individuals to decide on their messaging and post where they saw fit. To date, over 260,000 people have taken part in over a hundred countries.

“Why would I go into the middle of Palestine and paste a giant image of a girl who lost her parents in a bombing, when the locals do it so much stronger?” JR argues. “That was a piece I had nothing to do with; they even printed it themselves. They just used my dots, to show it was part of the project and so they won’t be targeted for producing propaganda. That’s the best combination I could imagine.”

Fraught geopolitical tensions have also served as key inspiration for some of JR’s latest works, which examine and unpick the unsavoury attitude towards immigrants held by the current US government. Earlier this year he presented So Close at The Armory’s Pier 94 in New York, where archive photographs of migrants arriving on Ellis Island were doctored to include faces of contemporary Syrian refugees. It was something of a sequel to his 2014 piece that took place on the island itself, where he pasted historical imagery throughout the immigration facility’s abandoned hospital complex.

In an even more overt critique of contemporary US policy, JR presented an unmistakably joyful image of a toddler looking over the Mexican border in September last year. At seventy feet, this young boy dwarfed the barrier dividing Tecate from San Diego County and made something that is normally associated with fear and anxiety seem faintly ludicrous. The public response was exceptional. Thousands of tourists came from both sides of the border to snap selfies with the structure (built on the Mexican side), with visitors even passing their phones to one another through the barrier, in order to get a better shot. Despite using a digger, hiring scaffolding and creating this huge cut-out, JR encountered little resistance from the border control:

“ If everyone says ‘yes’ why should a man sitting in an office stop it happening? That’s why I do a lot of my work illegally”

The piece culminated with a picnic on both sides of the wall, with guests sharing food through the fence and a band splitting up, to perform on both sides. The event featured a custom tablecloth depicting the eyes of a Dreamer (the name afforded to undocumented people who came to the US as children). The act was a particularly poignant moment, considering the current perilous state of the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) programme. In fact, the Dreamer in question attended the event with her mother, despite the very real danger that she might face deportation, as she felt it was too important and symbolic a moment to miss. “It gives me hope, about what is possible and what is not,” says JR. “You can think about how terrible this situation is… of course it is, and it’s very intense, but there are human beings behind this, who understand the complexity of these situations. Only certain art projects like this can reflect that. It’s not just my response, it’s thousands of people, so I can’t just be getting lucky! Maybe people are a little more open-minded than we think.”

This unquestionably positive attitude permeates JR’s work, and his exuberant story-telling around the people he has met has even manifested itself in documentaries. His latest endeavour titled Faces and Places follows his journey with fellow French artist Agnès Varda (a prolific, experimental filmmaker), as they travel around rural France, equipped with a camera and a large-format printer. They seek out “normal people”, listen to their stories and commemorate them with—no surprises here—huge paste-up portraits. The film was nominated for an Academy Award (making Varda, at eighty-nine, the oldest contender to date) and JR’s Instagram feed shows images of him posing with Hollywood A-listers on the night of the Oscars. He’s in the mandatory tuxedo, but his glasses and hat are still intact. At this point you have to wonder, can he really continue to sustain this level of anonymity for much longer? For the sake of his art, one must hope so.

This feature originally appeared in issue 35

BUY ISSUE 35