Elephant writer Orlando Estrada visits Kembra Pfahler in her apartment (sometimes known as “Karen Black Headquarters”) and discusses life, death, and everything in-between.

Attempts to introduce Kembra Pfahler in words usually fall short of any kind of meaningful or tidy summation of her decades-long career. Best known for her unmistakable nude-with-total-body-make-up-look that she developed as front woman of the rock band The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black—and perhaps most infamously known for having her vulva stitched closed in the 1992 film Sewing Circle directed by Richard Kern—Pfahler is the enigmatic anti-hero of American performance art.

Earlier this year, in a collaboration with the reigning king of gothic chic and long time friend, Rick Owens, Pfahler released a capsule collection via the Canadian online retail platform SSENSE. Featuring logos and iconography of her rock band, TVHKB, as well as prints from her ongoing live butt- printing performance, the collection incorporates the boundary-crushing values that so often manifest throughout everything she does.

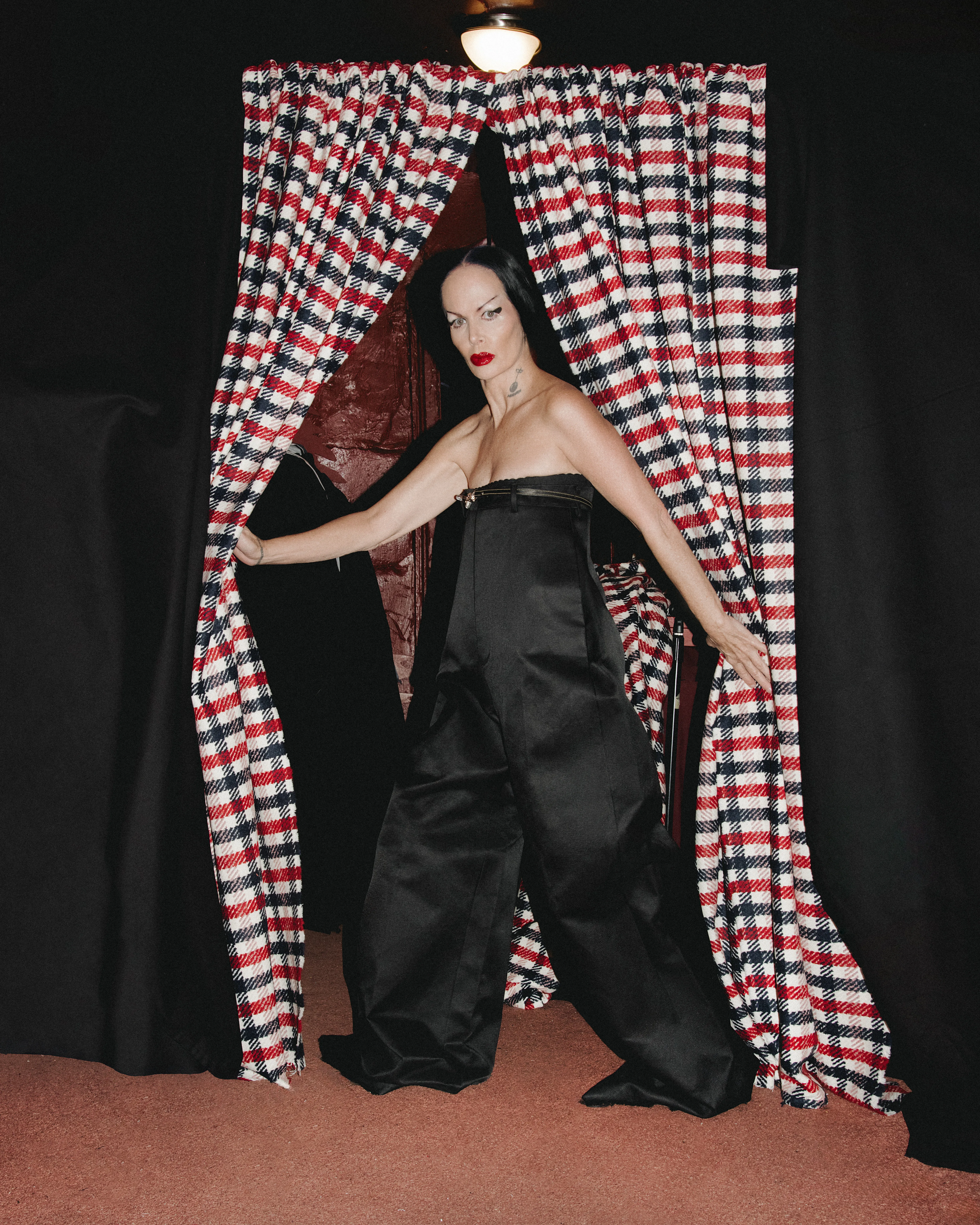

The ability of any individual to span cultural platforms, artistic meda and creative worlds seamlessly and with rigour is rare. Defying categorisation, the death-metal singer / model / experimental filmmaker / actress has been a defining force since emerging out of the New York 1980s Lower East Side scene. In her anti-domestic, and unrenovated tenement apartment, painted ox-blood red—including the floors and ceilings—Pfahler lives immersed in a time capsule of her feminine horror universe 24/7.

Sometimes referred to as Karen Black Headquarters, it is this apartment doubling as a primary working space that Pfahler chose as a setting to shoot this photo story for Elephant and where Orlando Estrada had the chance to speak with her.

OE: As time passes, we as humans all go through the four gates of life—birth, initiation, elderhood and death. What stage of life would you say you’re moving through currently?

KP: I’d say I’m in a constant state of passing through the last three—initiation, elderhood and death. Life right now in 2023 seems to pose daily initiations or challenges. Even at age 62, I feel like I’m always being tested and learning new things. It’s not a malevolent examination but a constant state of shock and wonder. Sometimes I need to re-learn the simplest things: how I engage with my peers, or how I speak with my siblings when we’re not on the same page concerning the care of our elderly parents. I’m also the leader of a band that does theatrical music, but utilises very traditional ways of practising the music we perform and record, and I’ve learned to accept each very different way that the musicians in my band operate. I’ve had to be so mutable all of these years. So I very much feel as if life is a constant sort of initiation. It’s my desire to always grow through these tests, despite the discomfort that comes along with this process. One of my band members told me about the word “liminal”, and learning about ”liminality” has helped me stop judging my process. For me, a “liminal phase” is the process of gathering, collecting and distilling the poetry, visuals, idiosyncrasies, accidents and discussions that take place while a new piece is being born, and finding what it communicates in this world. These new pieces must be bereft of “Appligence” or “Yesterbation”. I made up the word “Appligence” because I couldn’t find a word that specifically describes knowledge collaged from bits floating around on the internet. “Appligence” is the sort of intelligence that’s born of random deep-diving or complete trust in the apps that are downloaded onto our devices and then forever become quasi-truths. Sometimes when I’m listening to people speak, it sounds like a combination of the quotes and words of the day on the Internet—it’s like a constant slap in the face. “Yesterbation” is the romantic obsession with the past and constantly referencing it rather than forging ahead towards an uncomfortable newness that’s lacking in the majority of public opinion. There’s so much terror of the unknown right now. There’s terror of imperfection and failure, but it’s a necessary risk connected to growth.

“Elderhood and death” seems like a quote written on a metal plaque above a hallucinatory medieval doorway in the human mind. I’ve started to think seriously about the death of my mother and father, as well as my own passing. Not morbidly, it’s simply just what time it is currently. It started when I turned 50 years old—these issues pop up constantly now that I’m moving towards the end of my fourth decade as a full-time artist. I’d say life is certainly like a Rubik’s cube; it feels like a challenging puzzle and the riches of the experiences offered to me are always resting in the palm of my hand. The desire to fix or win is never as important as just using my brain and my heart to exercise all of the polemic, beautiful, complex, mundane and sometimes doltish qualities humans possess.

OE: You’ve used The Statue of Liberty in multiple works. Historically, the concept of liberty is associated with revolt, violence and the toppling of authority. Since the rise of far-right conservatism in the US, the concept of “freedom” has become associated with a much less sexy ideology. How do we make freedom sexy again?

KP: I always considered the Statue of Liberty to be a really beautiful sculpture. I do, however, think she should be painted pitch black. I love black so much because I see all of the colours in the spectrum in black. I see that in the black night sky as well—I always have.

I arrived in New York in 1979 and I remember going downtown with my mother and taking a water taxi that drove around the Great Lady. It was such an epic feeling to get so close to the monument. I imagined what it was like floating over from Europe in an intoxicated pirate ship filled with hungry European rejects. Can you imagine the tears that fell seeing her on the way to her new home next to Ellis Island? I wish Ellis Island were rebuilt by Walt Disney and that all of the new immigrants coming to the United States could go on rides and get soft-swirl ice-cream, hotdogs, and have a gentler welcome to their new home. Xenophobia is not sexy. The rise of the far right has escalated and eclipsed any benevolent ideology that existed in the United States in the past few years. The Constitution itself seems like fiction or sci-fi rather than a set of tools that perpetuate democracy. Freedom is now associated with a less sexy ideology because people take it for granted. Ask someone who’s done time in prison, or anyone who’s had to leave their country of origin, about the concept of freedom and sexiness; they must feel like there’s nothing sexier than having choices. It was pointed out to me that the Statue of Liberty has chains around her feet that can only be seen from an aerial viewpoint, the shackles representing her as a metaphor for formerly enslaved people. Now she’s free in the New York harbour. We’d only be able to make freedom sexy again if we had a complete spiritual revolution. Freedom is an elusive veil.

OE: Before social media made it easier for artists to reach a global audience, there used to be an informal tradition of artists reacting to traumatic historic events with creative actions staged for the public. How did you see the COVID-19 pandemic affect the artistic scene in New York City?

KP: The pandemic pushed a majority of artists who were financially unstable out of the city and only allowed a very small group of us to survive and work here. I remember the first year of the Pando when everyone fled New York City in abject fear. I got calls daily from people demanding to know how things were; they all felt so guilty. There was also a huge blush of financial confusion among many of my friends before they figured out how to receive unemployment benefits. During that time, I kept getting the most bizarre job offers from magazines and publications to speak about the scene here because there was a morbid belief that if enough people died and things returned to the 1979 disaster zone that was New York then, the city would somehow be interesting again. COVID 19 was like a disease war. It divided and separated you depending on which spiritual principles you lived by and your net worth. It created a more vitriolic class system. In some ways, it democratised being an artist, which is somehow lovely. The art world got a lot smaller and it’s also been wrung out like a dishcloth. You see older legendary art dealers without a gallery, you see blue-chip artists who’ve lost everything because they went out of fashion, you see new artists blow up and pop, which is always like watching a bloody train wreck. One day they’ve got the eyes of the world on them, the next they’ve got nothing. So the extremism of New York has become even more magnified through the pandemic. One of my least favorite things to do is to analyse the city. I was born in Los Angeles and came here in 1979 because literally everyone told me not to come to New York. The city was a disaster area back then. How New York has changed mostly is that people are really not as afraid of New York anymore. Too many people have come here only seeking fame and not contributing to the culture. Hollywood is the disease, not COVID 19. New Yorkers can handle any plague that hits us, but ostentation and celebrity is a sickness. Hopefully this will be out of fashion soon. Everybody’s an artist now. I stopped being an artist during the pandemic. I don’t really like doing anything that’s easy.

OE: Every avant-garde art movement from the turn of the twentieth century tried to dislodge the place of beauty in art. What do you think is beautiful?

KP: I’m not sure if art movements have a desire to dislodge the place of beauty in art as much as release a certain idea of beauty from captivity. Inspiration should be called ‘outspiration’. When there’s only one direction that beauty takes, it becomes predictable, and what’s most beautiful in artwork or music or fashion is things that are a surprise. I think most new movements or even non-movements in art change our perception more than anything. What we may have thought was ugly is simply a misinterpretation. There’s a difference between moving towards something that’s dangerous and moving towards things that are just not popular. Vanity is the enemy of interpretation. Our future is insatiable. In the future, it will be a felony to break someone’s heart. We’ll be able to have somebody else’s dreams at night. Real angels will rent space in our chandeliers and light fixtures; they’ll be a brand of outsiders we never expected. Black bubblegum will be chewable without turning our teeth black.

In the last several months we’ve all been witnesses of war, hunger, sickness, pain and illness that’s truly inexplicable. For some, it has vacuumed our bank accounts. Some people have had gains the size of Nebraska and sit in tiny little protective pods brooding and waiting to lose what they’ve finally got. The planet is so fraught with beauty, and its riches are coveted so strongly. It’s a terrific contradiction. Sharing is beautiful.

Words by Orlando Estrada

*This article first appeared in Issue 49 of Elephant Magazine. Available to buy now.