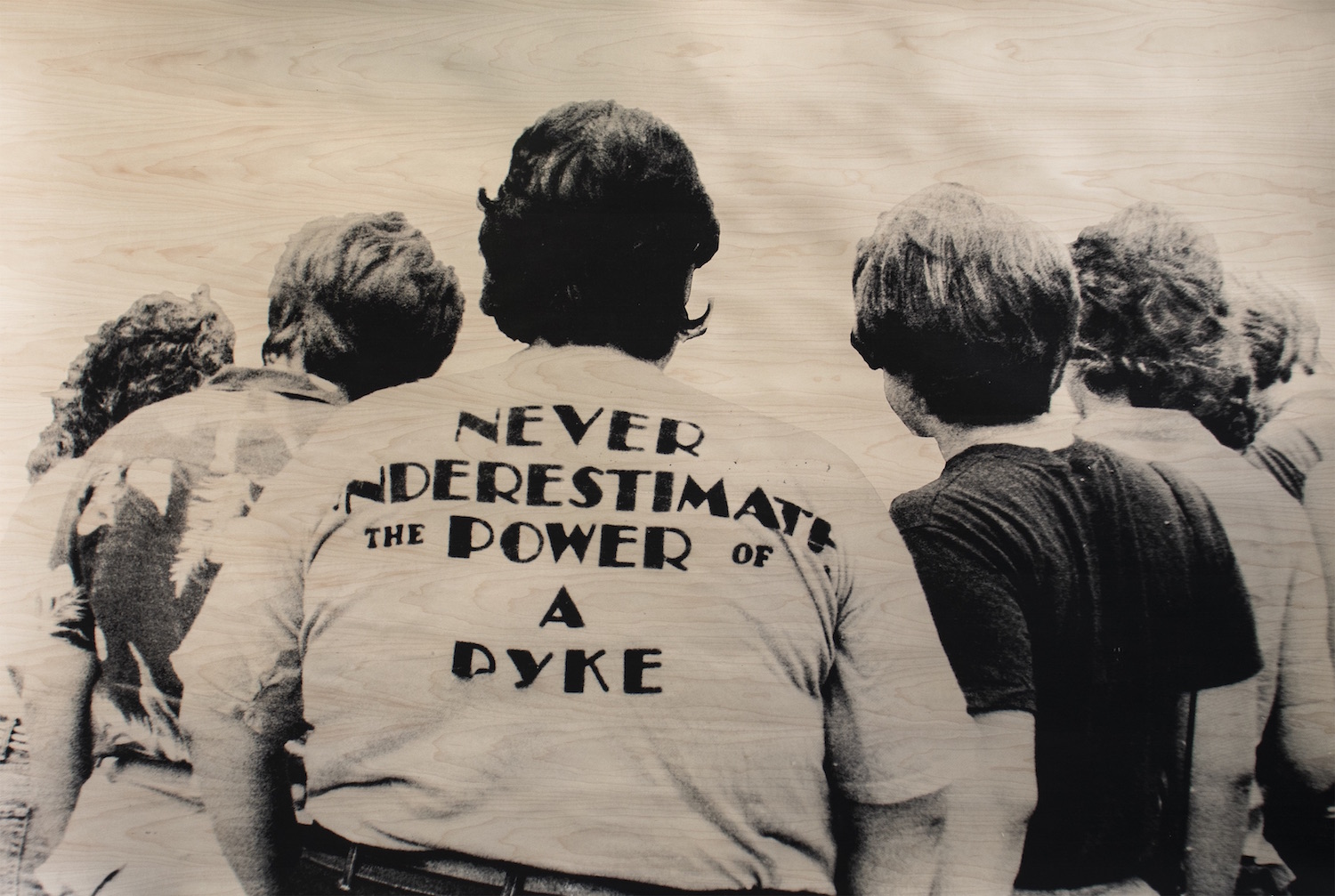

Never Underestimate the Power of a Dyke (Photographer Cindy Clark of Women’s Quarterly Journal), 2018. Maple Veneer, & Ink. Courtesy Victori + Mo and the artist

“History”, as it typically defined, is often curated, edited and skewed in ways that satisfy the mainstream narrative of the dominant culture and class within a given place. But, as someone from

the Bishopsgate Institute Archive in London told me when I visited recently, “history is more about us than it is about people we’ve all heard of”—the kings, queens, presidents and so on, who have been documented through the specific lens of whoever is doing the documenting.

As artist Phoenix Lindsey-Hall makes plain in her work, stories of the past are overwhelmingly histories, rather than herstories. While this erasure of women has remained a patriarchal, structural issue across the spectrum since time began, it’s especially pronounced for the lesbian community. This is for a number of reasons: many lesbians in herstory (the term we’ll be using for this piece, in-keeping with Lindsey-Hall’s work and its sources) felt too much shame to come out, let alone document their lives as queer women; in many countries homosexuality has been illegal (and in some, still is); and there’s a continuing pertinent sense of displacement for lesbian women who often feel excluded by both mainstream and phallocentric “queer” culture.

Earlier this year, Lindsey-Hall took inspiration from the

Lesbian Herstory Archive in New York City when creating a new series of pieces. The archive was founded in the 1970s by Joan Nestle and Deborah Edel as a means to document lesbian life and culture, with anyone identifying as a lesbian invited to donate to the collection. The artist found out about it when she was a sixteen-year-old in North Carolina, negotiating the tricky process of coming out. “They drive around the country on a motorcycle with a slideshow, so I went with my very first girlfriend,” Lindsey-Hall remembers. “Ever since then it became a magical place in my mind. When I moved to New York, I knew I would do a project with it, not just the fantasy of it.”

“The central focus is radical acceptance”

The archive states its purpose is “to gather and preserve records of Lesbian lives and activities so that future generations will have ready access to materials relevant to their lives,” and in doing so, “uncover and collect our herstory denied to us previously by patriarchal historians in the interests of the culture which they serve” through artefacts such as books; magazines; journals; news clippings from establishment, feminist or lesbian media; photos; films; diaries; oral histories; graphics and other memorabilia.

The focus of the archive is inclusivity for lesbians: there are no academic, political or sexual credentials required for using the archives, which are deliberately “housed within the community, not on an academic campus that is by definition closed to many women”, it says, of its site in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Unusually, the archives state they will always have a live-in caretaker, making it a home rather than an institution: a living, breathing collection rather than a dusty, revered, exclusionary one.

Lindsey-Hall’s work shares and celebrates this ethos. “It’s a very open space: you see people working on serious projects and PhDs and they also have kids who come for their queer book reading circle,” she says. “One of the things I love is that the central focus is radical acceptance: anyone who identifies as a lesbian or feels they belong there can go and give them pieces for their collection. That means you’ll find Audre Lorde’s papers and other very significant objects but also love letters and concert tickets. Together, that builds a collective consciousness of the cultural significance of the community.”

“There’s a continuing pertinent sense of displacement for lesbian women who often feeling excluded by both mainstream and phallocentric ‘queer’ culture”

Lindsey-Hall’s exhibition at the recently opened Victori + Mo gallery in Manhattan, entitled Shame Is the First Betrayer, drew source material from the archive. The show takes its name from Nestle’s poem about walking through various New York sites as navigated by the dynamics of a butch/femme couple, underscoring “the violence that can happen in the street for queer and butch people”, says Lindsey-Hall. For one piece the artist used lines from the poem as strips that formed a woven rag rug. “The lines of text weaving together as a tapestry felt emblematic of the way the whole archive is put together: everyone has personal artefacts that when put together become about so much more than one individual.”

- Phoenix Lindsey-Hall, Shame Is the First Betrayer, install image, courtesy of Victori + Mo

Throughout the show, Lindsey-Hall drew mostly from texts and photographs in the archive in which people describe themselves; as well as pieces that give a snapshot of queer life in the sixties and seventies. These were then worked into pieces made from materials including wood, textiles and, for the first time, printed ceramics. The installation-based show became both an homage to the Lesbian Herstory Archive through a visual reinterpretation of its history and a way of uniting present-day experiences with those of women from the past.

“I really liked exploring how you can take archival materials and use them with a very fragile medium”

Her previous works have largely focused on photography and sculptural pieces, so it was something of a departure. “I’d been experimenting with screenprinting onto ceramics and really liked exploring how you can take archival materials and use them with a very fragile medium—so many of the slabs you make break, and the messiness of the screenprinting adds another layer of history onto it,” she tells me. “We’re all familiar with ceramics as a material but it invites a new perspective when you use it in a new way. It’s like when a plate you’ve washed a thousand times before explodes finally when you wash it: there’s a latent pregnancy in the material—a preciousness and history around. Addressing living history and living legacy felt similar.”

While the medium was a progression for the artist, the subject matter is a familiar one. Lindsey-Hall is behind the participatory art project Lesbian Matters, which explores the personal and material things we accumulate throughout our lives such as postcards, trinkets, letters, photographs and button badges (and even a bag of testosterone) submitted by people that aim to “serve as reminders of life’s queer moments”. As the artist points out, the same object but by different people carries different meanings; something that was at the heart of her explorations of individual lives as part of the collective queer experience in the project. “A lot of people can have a pocket knife—it’s not a ‘lesbian object’, but it’s about the meaning that’s been imbued into it, as a symbol of masculinity, but in a positive way, showing the significance of an object that had been private and put in a space with those from other people.”

“Lesbian can be a loaded word: it can be tough sometimes to claim your own space. I wanted to own and claim it and call a spade a spade”

It was important for Lindsey-Hall to use the word “lesbian” in the title rather than broader words such as queer. “Lesbian can be a loaded word,” she says. “For lesbians it can be tough sometimes to claim your own space. The word might feel exclusionary for people who are more gender non-confirming or who don’t fully identify as lesbians; but I don’t necessarily hear people having the same conversation around the word gay—that’s more an umbrella term. But there’s something about women and wanting to be inclusionary—it’s a multilayered thing. But I wanted to own and claim that word: whether people are femme or butch or gender non-conforming, it felt important to call a spade a spade and let people have a reaction.”