At a press conference on Friday morning, Antoine de Galbert, collector and founder and director of Paris

’s La Maison Rouge, asked journalists to please focus on the exhibition that has just opened, and not on the imminent closure of the space, founded in 2004. It’s a difficult request though, not only because of the cultural significance of the end of such a staunchly Parisian foundation, whose cessation was announced last year, but because the exhibition itself also smacks of nostalgia. Such a qualification might sound snarky, but it’s not intended to be judgmental. L’envol is a show curated by De Galbert and his three mates: art brut collector Bruno Decharme, gallerist Aline Vidal and philosopher Barbara Safarova; a last hurrah organized over long dinners and group holidays, reflecting on the melancholy thematic of the desire to fly.

Some parts of the show are questionable, there is a large “ethnographic vitrine” set at the back of the space, supposedly as a means of demonstrating “how we have always wished to fly” with the glass divider signifying “difference in intent”, as these shamanic or historical objects apparently do not fall within the same category as the more contemporary art objects on display. Such a discourse instantiates an uncomfortable narrative of evolutionary or cultural disparity, placing the objects at an exoticizing distance. So-called ethnographic art has always been somewhat on the agenda at La Maison Rouge and the nuances of this problematic genre within France merits an entire essay in and of itself.

“There has been no overriding theme during La Maison Rouge’s existence, no dogmatic plan”

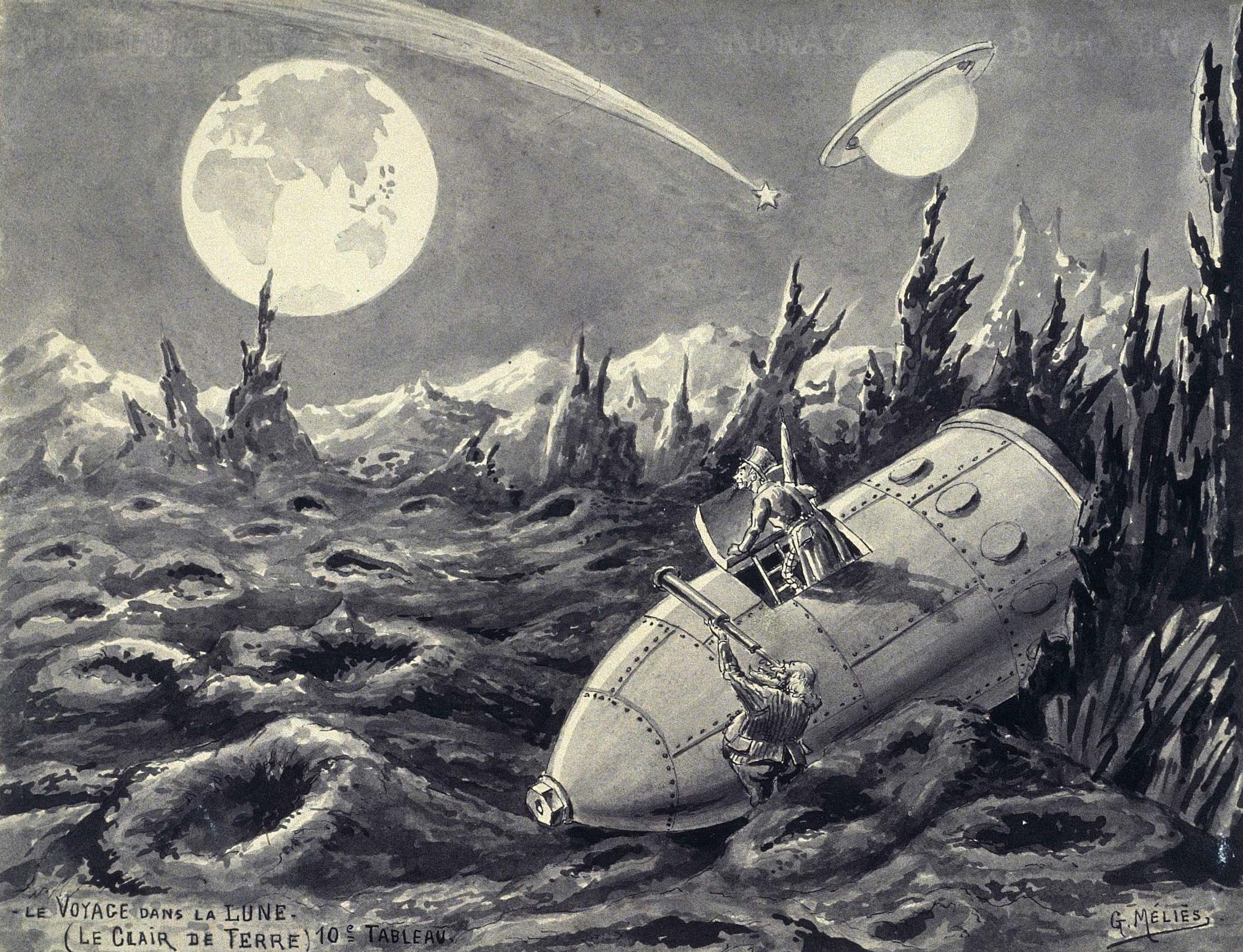

There are, nonetheless, a few stand out pieces: a series of lyrical, meditative videos put together by the Centre National de la Danse with choreography from Non Nova, Heli Meklin and Angelin Preljocaj; a number of black and white anonymous photos staging a man in thigh-high leather boots with a small winged instrument in hand, and Fabio Mauri’s Luna (1968),

an immersive installation where visitors can wade knee-deep through tiny, light, polystyrene balls and exprience what Mauri imagined the surface of the moon might feel like, a year before anyone actually knew.

The whole thing is quite weird and wonderful. At one point, Vidal runs to the back of the basement room and crouches down beside an immobile young performer, part of Pierre Joseph’s La Sorcière (1993). The performer is flat on the floor, limbs disjointed, dressed as a witch, with her head crushed against the back wall and (hopefully fake) blood running down her cheek. Vidal squats down beside her and takes a photo while the girl looks genuinely in pain. “We’ll set you free soon,” she laughs.

This giddy mood has often defined the spirit of La Maison Rouge. It has always been a place that stages accessible exhibitions that for the most part resist becoming gimmicky; Under the Influence in 2013 narrowly avoided being a show aimed solely at seventeen-year-old stoners, and instead took stock of the vast scope and diversity of the influence of psychoactive drugs on artistic output, looking at work by Cocteau, Degas, Henri Michaux, Francis Alÿs and Carsten Höller, and focusing astutely on the work rather than simple biography. In 2007 the foundation staged Sots Art, a daring exhibition of Russian political art from 1972 to the present day, platforming an important period that would see the emergence of the first avant-garde movement following socialist realism, which had reigned since the twenties.

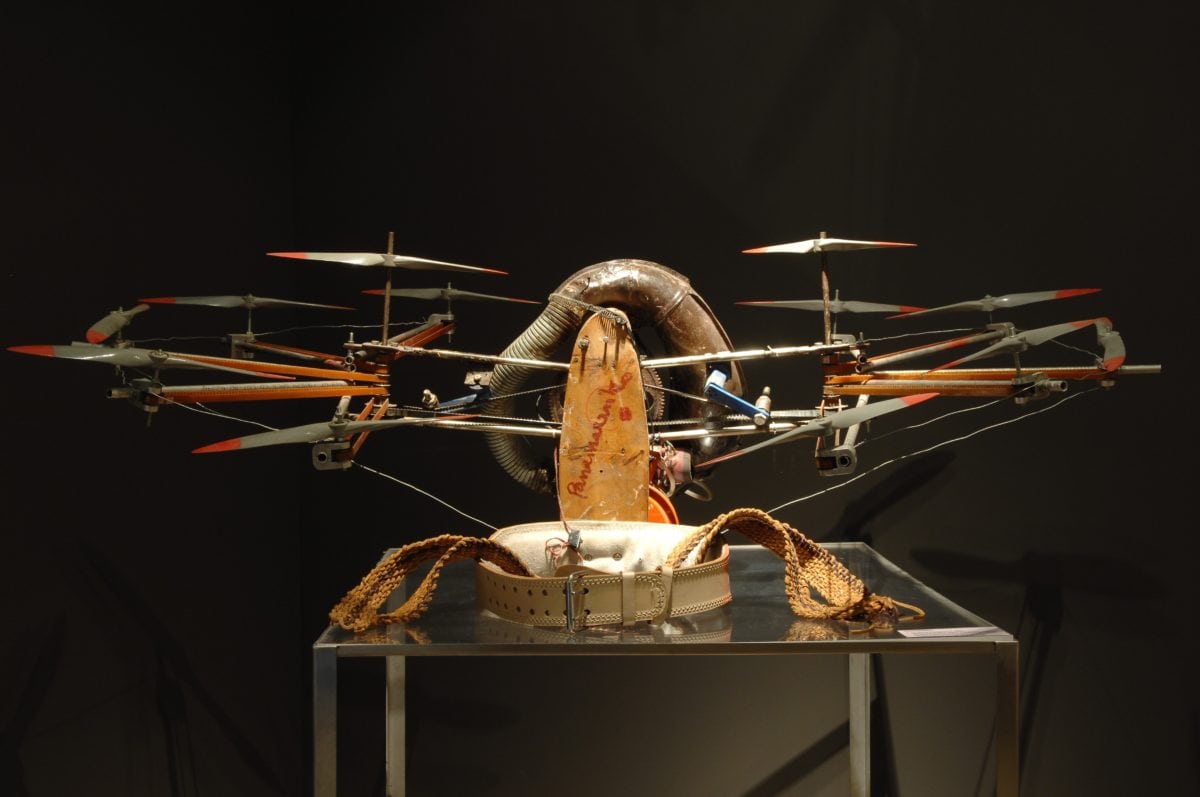

- Panamarenko, Japanese Flying Pak 3 (2001) Copyright Panamarenko. © Galerie Jamar, Antwerp. Photo: Wim Van Eesbeek

- Sthembile Msezane, Chapungu, The Day Rhodes Fell, 2015 © Sethembile Msezane. Courtesy private collection

The foundation invited curator Andreï Erofeev—who was subsequently fired from his post at the Tretyakov Gallery for “defaming” Russia. In 2009 the space gave Mika Rottenberg her first institutional solo show in France and in 2013, it brought the collection of Australian gambler-cum-art collector David Walsh to the country. Walsh is at the head of the spectacular Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Tasmania, which is arguably a more successful melding of non-Western objects, contemporary art and antiquities.

There has been no overriding theme during La Maison Rouge’s existence, no dogmatic plan; the foundation would oscillate from art brut, to contemporary, to exhibitions about comic books or the presentation of private collections, themselves wildly diverse in scope. Yet it didn’t ever feel incoherent. With De Galbert as the financer and president of the space, it simply marched to its own beat.

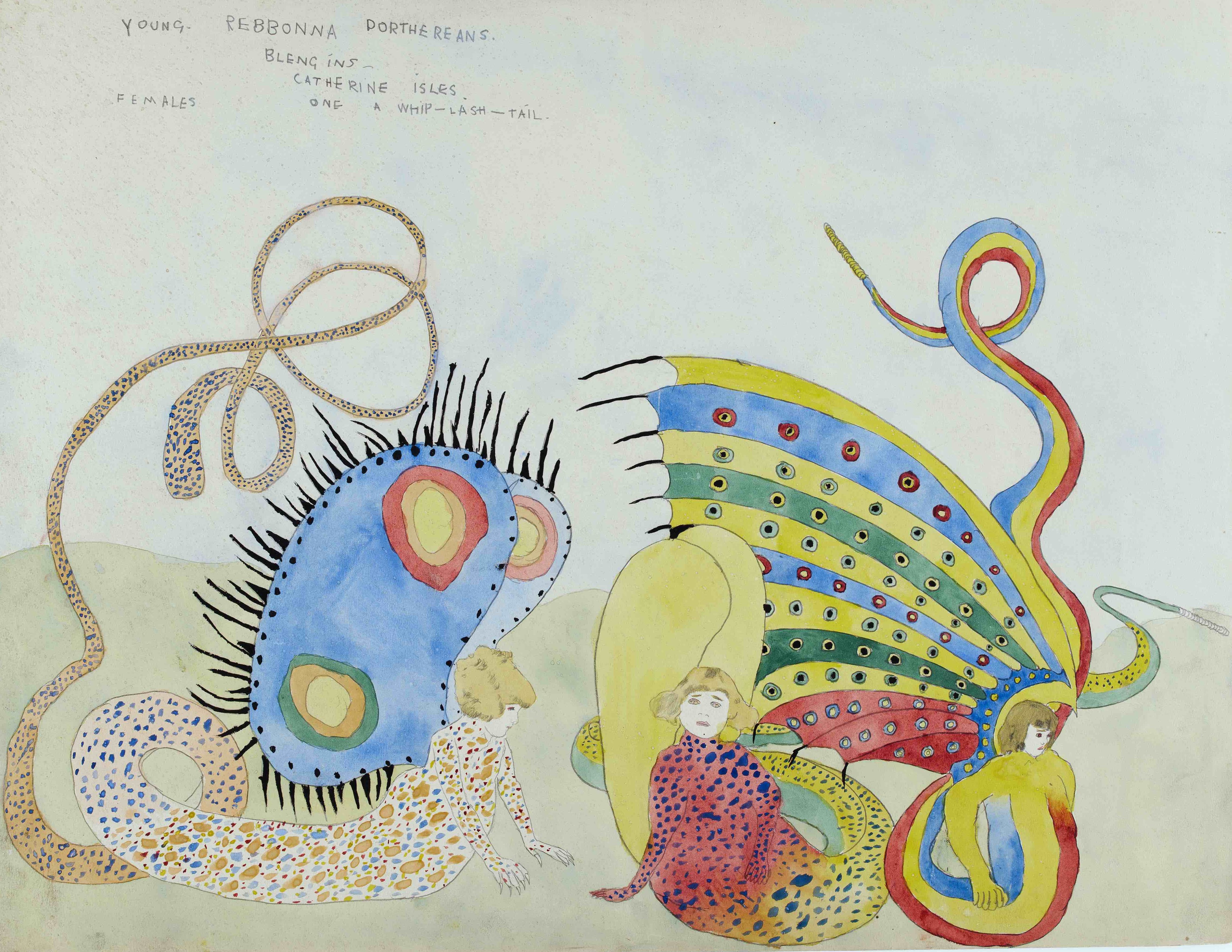

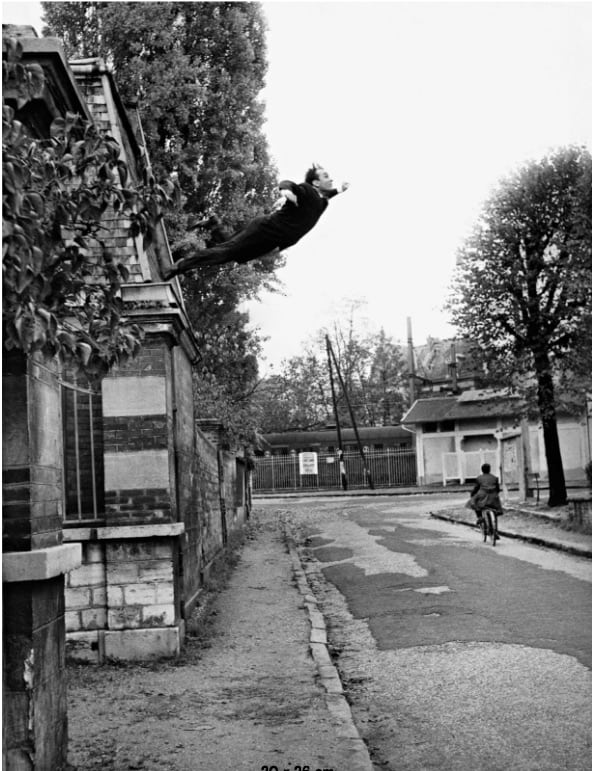

While rumours might be afloat that De Galbert’s fortune is dwindling, or that the sixty-two-year-old’s health is failing, he discounted any such claims in an interview with Le Monde earlier this year, stating instead a desire to quit while he was ahead. The concluding exhibition at La Maison Rouge is an easy metaphor; De Galbert is flying away from this particular project, filled with works such as Yves Klein’s iconic Saut dans le Vide (1960), Lucien Pelen’s Chaise n°2 (2005); mystical imaginations by Henry Darger and fanciful contraptions like Panamarenko’s Japanese Flying Machine (2001). There is something of the Wizard of Oz about it all, the great man taking off in his hot air balloon, waving back affably.