Last year, in the midst of a pandemic, I found myself accepting an unpaid writing gig. I had pitched an idea to a prestige American publication who were running a series of personal essays related to the experience of lockdown. When asked about the fee, they informed me that there was no budget due to a spending freeze, and that it had been a “labour of love” for all involved. It came as a shock to me, not least when I reflected upon the writers that I admired who had already contributed to the series. They had all agreed to work for free; shouldn’t I do the same? But as my deadline approached, I realised that I couldn’t bring myself to write for them. It was as if I was internally rebelling against my own former judgement. In the end, I never submitted that piece.

In the creative industry, the question of what our work is worth comes up again and again. My dilemma was unfortunately all too common, and is indicative of a pattern of behaviour that sees creative workplaces shift the burden of financial responsibility onto their employees. Individuals are pressured to accept lower pay in order to support not just their employer but a holistic vision of the arts. Following the negative financial impact of the pandemic on the sector, it is inevitably the employees and freelancers who will continue to absorb that burden. Just this week, a prominent member of the City of London’s governing body faced a backlash after he stated that staff at the Barbican arts centre should not “feel too sorry” for themselves because they still had jobs, according to a report in The Times. In other words, they ought to be grateful to have employment in the arts at all.

“Individuals are pressured to accept lower pay in order to support not just their employer but a holistic vision of the arts”

It is often suggested that the prestige or perceived opportunity that comes with a job can compensate for lower financial remuneration, but is it enough? The correlation between prestige and poor pay is reflective of a growing imbalance of power in the industry, whereby renowned institutions are able to leverage terms of employment that go beyond the purely monetary. Last month, more than 100 employees represented by the New Yorker Union undertook a 24-hour strike to demand “fair wages” and “a transparent, equitable salary structure”. As they explained, “We are committed to The New Yorker, which is why many of us have worked here years—even decades—despite low and stagnant wages. However much we may love our jobs, that love is not enough to live on.”

Of course, the amount that you are paid signifies more than just your bank balance alone. For creative practitioners in particular, the boundary between work and self-image is frequently blurred, and it can be difficult to disentangle the fee for a job from a sense of self-worth. Money can also be an external motivator, for better or worse, particularly in moments when it is otherwise challenging to muster the creative focus required for a project. While this association undoubtedly plays into a wider capitalist framework, the two remain intrinsically linked. As we continue to exist within a system that thrives on competition and speculation, workers are encouraged to undercut one another even despite themselves—and those who can afford to ask for less come out on top. From unpaid internships to unpaid commissions, it is a cycle of exclusion that never seems to stop.

Lately I have been reflecting on a very different form of unpaid creative work. In the heyday of the blogosphere, circa 2000-2010, the internet was awash with LiveJournals, Tumblrs and Blogspot diaries that chronicled the innermost thoughts and inspirations of young writers, artists and photographers around the world. This was notably before the launch of Instagram in 2010, when the now-familiar gridded format swept aside the informal communities of bloggers. I published a free blog from 2006 until 2012, while I was still at school and later at university, and look back on it as a time when the internet seemed less fixated on making money. Brands, targeted advertisements, influencers and sponsored deals were not yet the norm, and these blogs offered a space for experimentation and self-expression.

“In the heyday of the blogosphere, circa 2000-2010, the internet was awash with LiveJournals, Tumblrs and Blogspot diaries”

A potential successor to those blogs has recently emerged. Substack, a service that enables writers to send long-form email newsletters directly to their readers, has been steadily growing since its launch in 2017. Could this represent a new era of independent digital publishing? The success of Substack during the last year, when the media industry has seen over 30,000 job cuts in the United States (more than 200 percent of 2019 levels), suggests that its growth is directly connected with the impacts of the pandemic. Out-of-work journalists, suddenly with more time on their hands, have found an alternative outlet to traditional media. Users of the platform have the option to monetise their newsletters via a paid subscription model, but many choose a mixture of free and paywalled content.

While it is easy to reflect on the halcyon days of blogging with nostalgia, it is evident that the privilege to publish creative content purely for the love of it is not one that is afforded to all. I stopped publishing my blog when I entered the world of work, initially holding down a part-time job alongside a full-time internship that left me exhausted. I still believe that the value of creative pursuits cannot be measured in financial terms alone; they offer therapeutic benefits, alternative forms of community and opportunities for personal reflection. But there remains an important distinction to be drawn between working for yourself, and working for institutions who co-opt the language around creative production to encourage unpaid work. Until we move beyond the endless refrain of the “labour of love” in the creative industry, it will remain a sphere that is closed to those with neither the luxuries of time nor money.

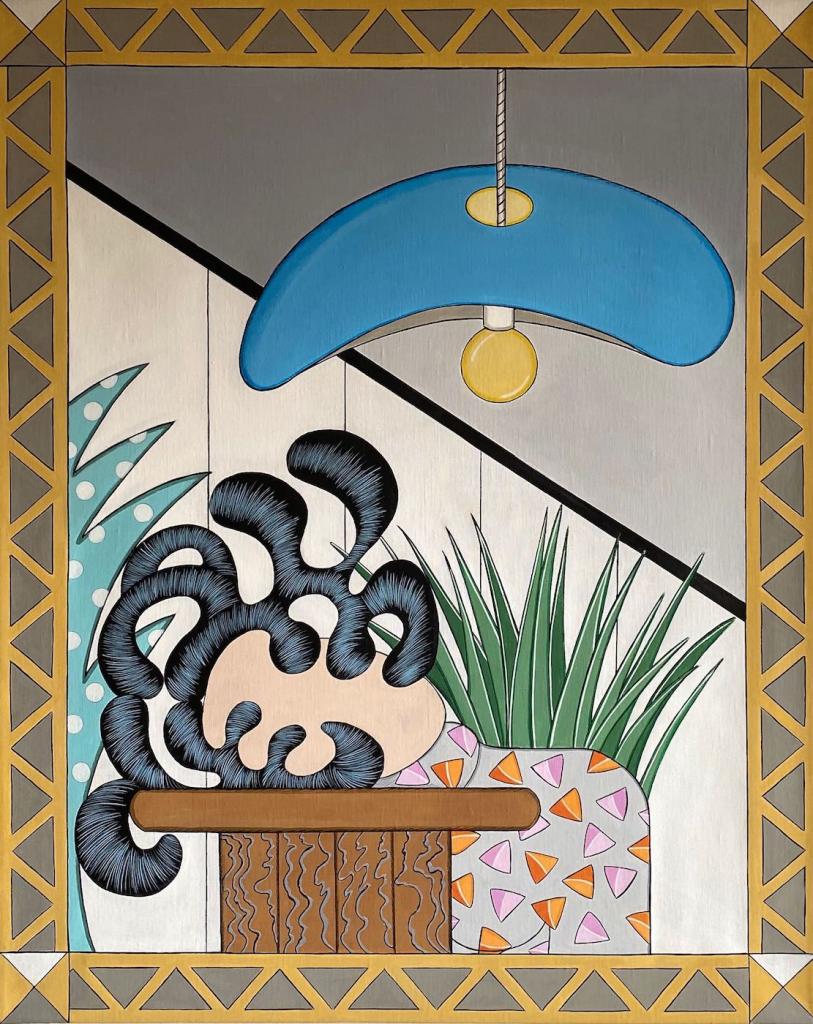

Are We There Yet is a fortnightly column by Louise Benson. Top image © Deborah Druick