New York- Signage throughout the Met’s corridors guide visitors to a discreet queue located deep inside the museum. From this point, an elevator leads to the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden – the site of Lauren Halsey’s new outdoor commission, The East Side of South-Central Los Angeles Hieroglyph Prototype Architecture (I). Both spectacular and touching, the monument to the community from which the artist hails sparks an almost visceral questioning of societal structures of power, architecture and the value systems the global West places on the African body.

The technical depth to which visitors must travel into the building to reach the Roof Garden feels symbolic of the conceptual depth of the work itself. Halsey’s colossal installation evokes a similarly exaggerated grandiosity as the anatomy of the building atop which it is installed. The MET is an architectural chimaera, expanding through various structural additions since 1888, with facades of previously exterior walls now visible as interior partitions separating several first-floor galleries.

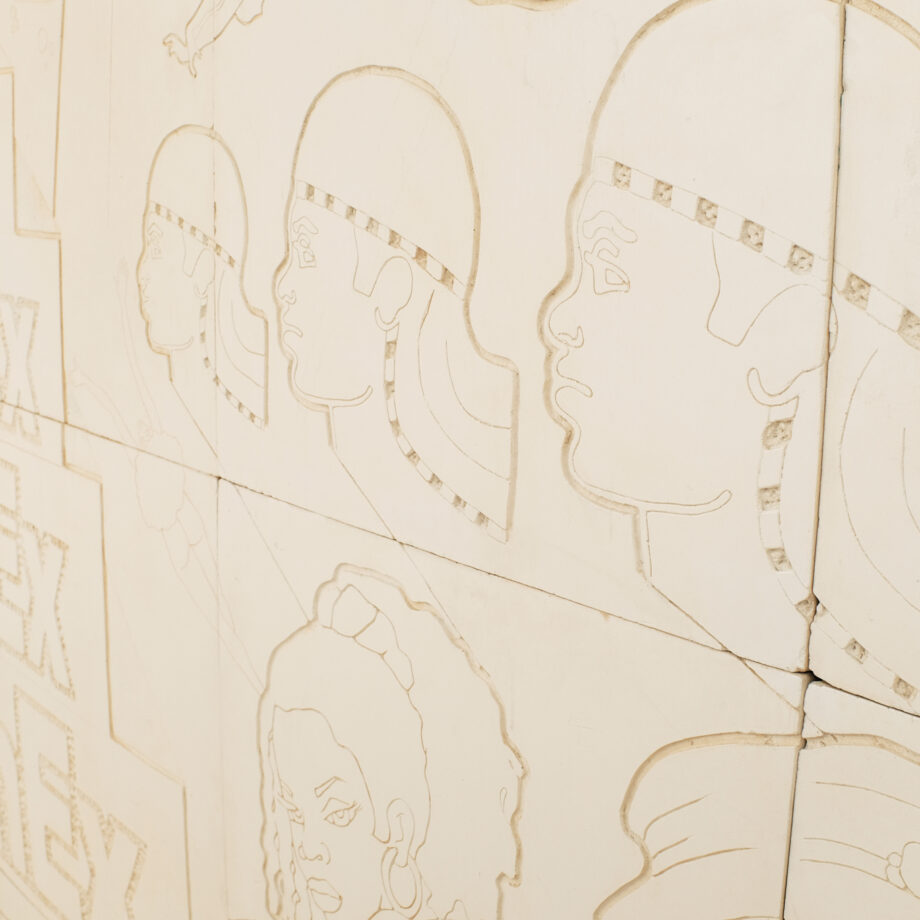

On approach, the viewer first encounters Halsey’s work through an etched series of heads arranged in rows reminiscent of traditional barbershop imagery. The viewer can only see the back of these heads, their hair textures and varied stylings reveal that they are in fact Black people. If we are to consider architecture in relation to the human body or as a body itself, the presence of these heads feels particularly significant. The monument is the building’s newest appendage- a new Frakenstienian head.

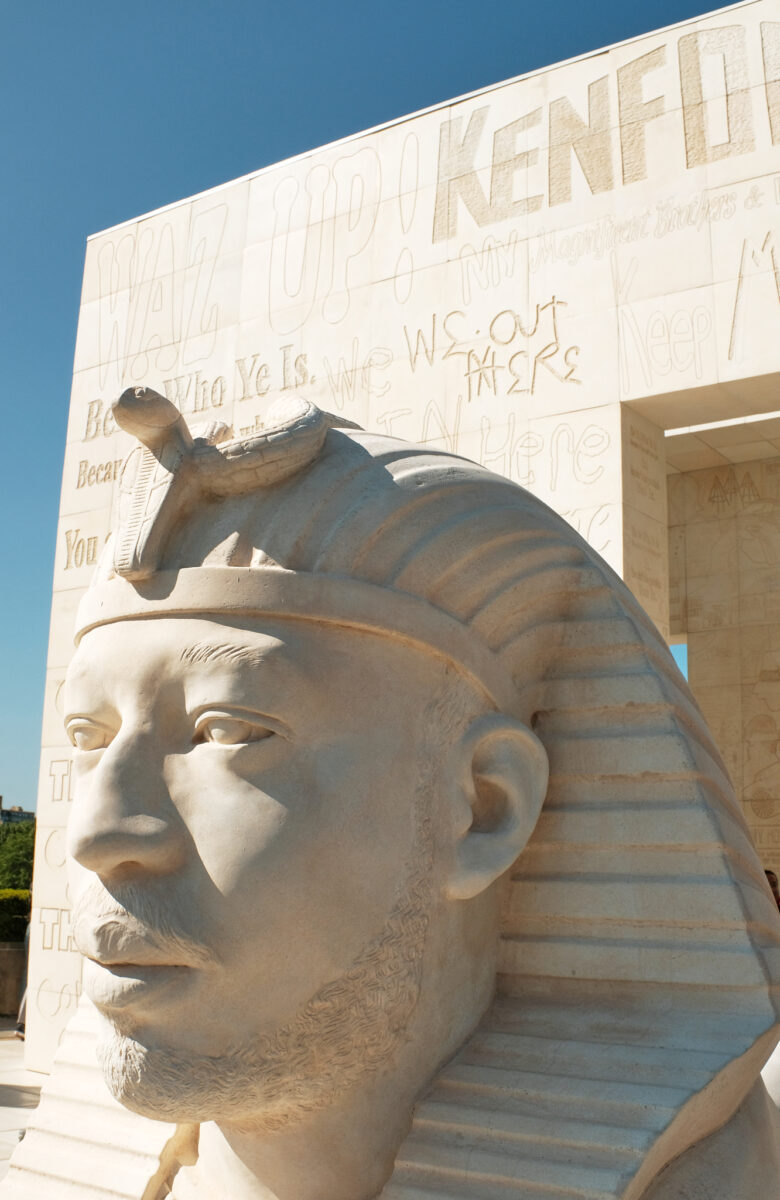

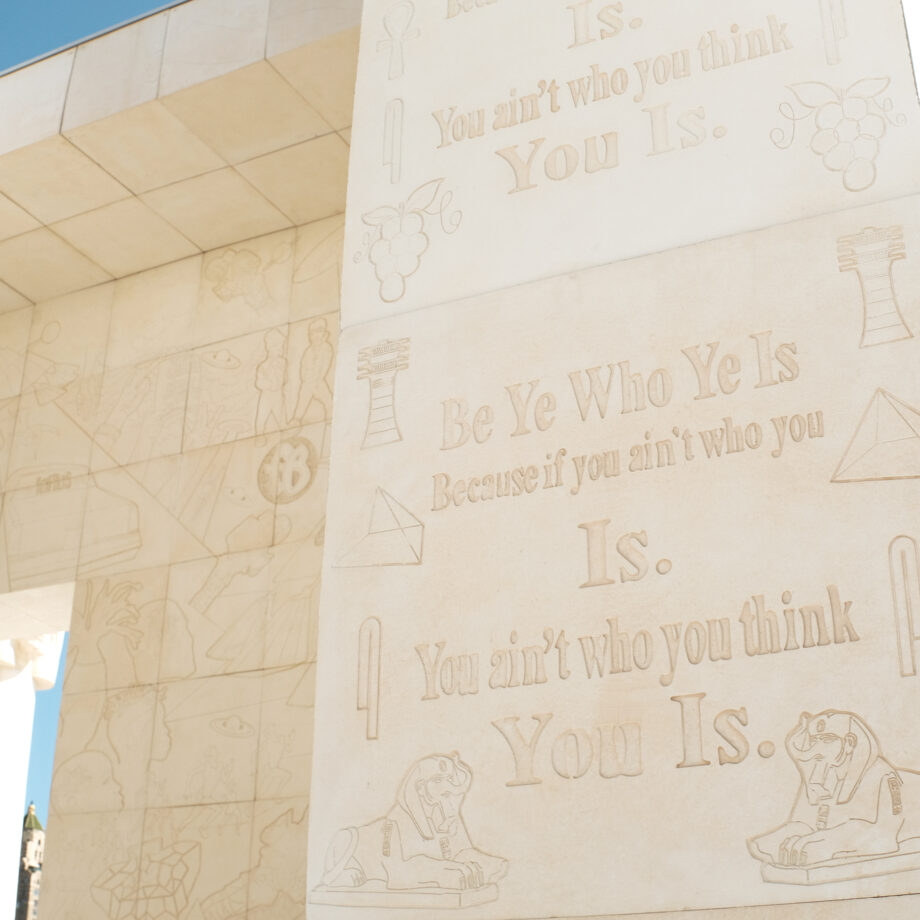

The chimaera metaphor is reflected in Halsey’s bas-relief work itself. Composed of over 750 engraved concrete panels, the walls of the central structure feature what the artist calls “contemporary hieroglyphics”. These etchings of stylized text and images from modern times are made timeless through Halsey’s formal transmutation. Columns and sphinxes featuring the likenesses of the artist’s family, friends and community members surround the main form. The East Side of South-Central Los Angeles Hieroglyph Prototype Architecture (I) marries the strict concrete geometries of 1970s Brutalist buildings and the functional sacrality of ancient Egyptian temple complexes with delicacy.

The structure’s walls that face towards the New York skyline feature words of affirmation in various typefaces. Exiting from the museum elevators and moving through the passageways of Halsey’s work feels like symbolically traversing through a representation of the Black mind, entering through the back of the head and exiting through the mouth. Does the work represent a portal into and through “Black thought”? My focus keeps oscillating between the invented hieroglyphics etched by Halsey onto the shimmering white tiles and the bodies of visitors moving through the space itself. Sun beaming down, I notice that the highly reflective surface of the monument hurts to look at for too long.

Drawing her inspiration for the work directly from the Column with Hathor-emblem capital and names of Nectanebo I on the shaft, Late Period, 380–362 B.C., in the Egyptian collection of the Met, I find one of the most curious aspects of Halsey’s self-proclaimed Afrofuturist monument is that in actuality, it is modelled after structures in states of ruin.

While there is evidence that the Great Pyramids of Giza, now seen in their ruined form, were originally completely encased in polished white limestone so reflective that their light could potentially have been seen from outer space, the Met’s Column with Hathor-emblem… was originally ornately coloured. An apparent dichotomy between the futuristic conceptualization of architecture and its current ruined state pervades this work. I see this tension in the artistic decision to present The East Side of South-Central Los Angeles Hieroglyph Prototype Architecture (I) with a bleached surface. Here we have a white sculpture modeled after ruins of elaborately painted temples as a monument to the future of South Central LA’s Black community. Is this a symbolic acknowledgement of covetous Western imperialism over ancient Egypt?

The monument’s blinding whiteness can be interpreted as the devastatingly pervasive “White Gaze”. Halsey also opted for the extensive use of the white “colour field” in her earlier grotto works. These loosely geological formations feature excavated vignettes which form still-lifes of fantastical Black life. Incorporating collected figurines, magazine cut-outs and other elements, these utopic scenes are sweet, endearing and colourful. Again, there is an exchange between pervading whiteness and colour. An even more powerful through-line is the symbol of excavation.

This artistic gesture is technically applied in Halsey’s grottos and the bas-relief work in the architecture and conceptually in her mining of the South Central LA community for source material. Through the act of physical and theoretical excavation, I find another curiosity, Halsey’s work is not contending with the societal fabric of the ancient world at all. It is an aspirational interpretation of African ancestry through the lens of Western Egyptomania of the 1920s and 30s.

When the Egyptian department at the Met underwent its most significant expansion, between 1906 and 1935, aristocrats from New York took excursions to Egypt and brought back plundered antiquities to the United States to build private collections. Perhaps most eccentrically, people brought back mummies, and parts of mummies, to hold unwrapping parties to ogle the desiccated bodies of North Africa’s elites. It is rumoured that the most daring participants at these gatherings even boiled, cooked and consumed parts of the preserved remains. What can we make of this performance, if not the physical manifestation of the Western desire to consume and embody the cultural essence of ancient Africa?

Like Halsey’s collections of plastic figurines and Black memorabilia, the collections of this period accrued value beyond monetary capital and became symbols of status and power- many of these private collections have been acquired by the Met. If I am going to anthropomorphise further the architectures of Halsey’s work and the building of the Met, I must also question the value systems the global West places on the African body.

At its core, criticism is supposed to make the thing it is critiquing/criticizing better. I am not interested in institutional critique but in situationism and nuance. I do not want to participate in the political and cultural wars of bipartisanship, and I applaud the Met for selecting a Queer, Black, Female artist from a historically disenfranchised community who chose to contend with those weighty histories for this commission. Halsey has an uncanny sense for honourable and loving representations of her community and, through her work, portrays a contemporary Atlantis, under threat from developers hungry to capitalise on land that was first stolen from Native Americans, now being systematically removed from the hands of its Black inhabitants. I see gentrification as a continuation of colonialism – no less violent than the genocides launched against the indigenous people of North America.

Black people are often treated in White societies as an alien species – a potent and satirical entry point into the Afro-futurist universe. Afro-futurism partly developed due to the loss of family histories that precipitated following the trans-Atlantic slave trade when African people were kidnapped and forced to labour under sadistic and terrorizing circumstances. Black bodies were reduced to their objecthood, automatons for the advancement of capitalism. I cannot help but think of the mummified African bodies simultaneously on display in the Egyptian wing of the Met. I do not have the insight to launch a discussion on repatriation, and that is not the point of this text – but it is something I must consider in relation to the symbolic crown Lauren Halsey has placed on the Met. Does this exhibit mark the paradigm shift within institutions where the value of Blackness has been freed from the objecthood of the human body? Is this the point when institutions will begin to consider the importance of Black thought greater than that of Black capital?

It is profound to encounter an afro-futurist monument, modeled after ancient ruins, on an obscure terrace overlooking Central Park. There is a smoothness, a slickness, a cleanness that feels like a movie set or stepping foot into the seamlessly fabricated facade of a Walt Disney park. The tiled floor creates a threshold between a hybrid interiorization of outdoor space – a pavilion. An experiential and deeply philosophical collapsing of time takes place, one anchored in institutional canonisation.

Words by Orlando Estrada

The Roof Garden Commission: Lauren Halsey

18 April-22 October 2023

The Met, Fifth Avenue, New York City