What

In 1960, Zürich art collector Heidi Weber presented modernist architect Le Corbusier with a unique brief: to design a pavilion to house her collection of his own artworks and design objects. It would be his final project, a fitting capstone to a career characterised by flagrant self-promotion. “This house will be the most audacious of my career,” he wrote. For an architect who had tirelessly promoted grey reinforced concrete, the design was a bold sidestep, with Rubik’s Cube-esque blocks of colour, a floating roof and a featherlight steel frame.

Completed two years after Corbusier’s death, Weber kept it as a complete work of art until the land lease expired in 2014, when Zürich’s local authorities took over. But disputes over the removal of her name from the museum led Weber to withdraw her collection. Undeterred, the authorities arranged a programme of temporary exhibitions of Corbusier’s work, and handed the running of the house to the Museum für Gestaltung. It reopened in 2019 after a two-year refurbishment.

“The Pavilion is one of the few ways in which one can encounter a Corbusier masterpiece both inside and out”

Who

No modernist architect is as polarising as Le Corbusier, nor so influential—a remarkable feat given his lack of formal training. Born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret in 1887, he moved to Paris from western Switzerland in 1917, quickly throwing himself into the avant-garde art scene. In his journal L’Esprit Nouveau he began to publish a series of broadsides that came to define the contours of a new architectural model: favouring geometry, circulation and light over ornamentation. “A house,” runs his often-misinterpreted maxim, “is a machine for living in.” He would exercise these strictures in a string of villas now regarded as modernist marvels; the world’s first brutalist housing block; and Chandigarh, an entire Indian city built from scratch.

His architecture remains highly regarded, and 17 of his buildings were given UNESCO World Heritage status in 2017. But he has become a recurrent bugbear for his impact on urban planning. He also once daubed murals on the walls of fellow modernist Eileen Gray’s villa without her consent. Despite his outlandishness, many of Le Corbusier’s grandest ideas—such as the infamous Plan Voisin, which envisaged central Paris razed and replaced by concrete towers—inspired the rip-it-up-and-start-again, cars-before-pedestrians regeneration of the 1960s and 70s.

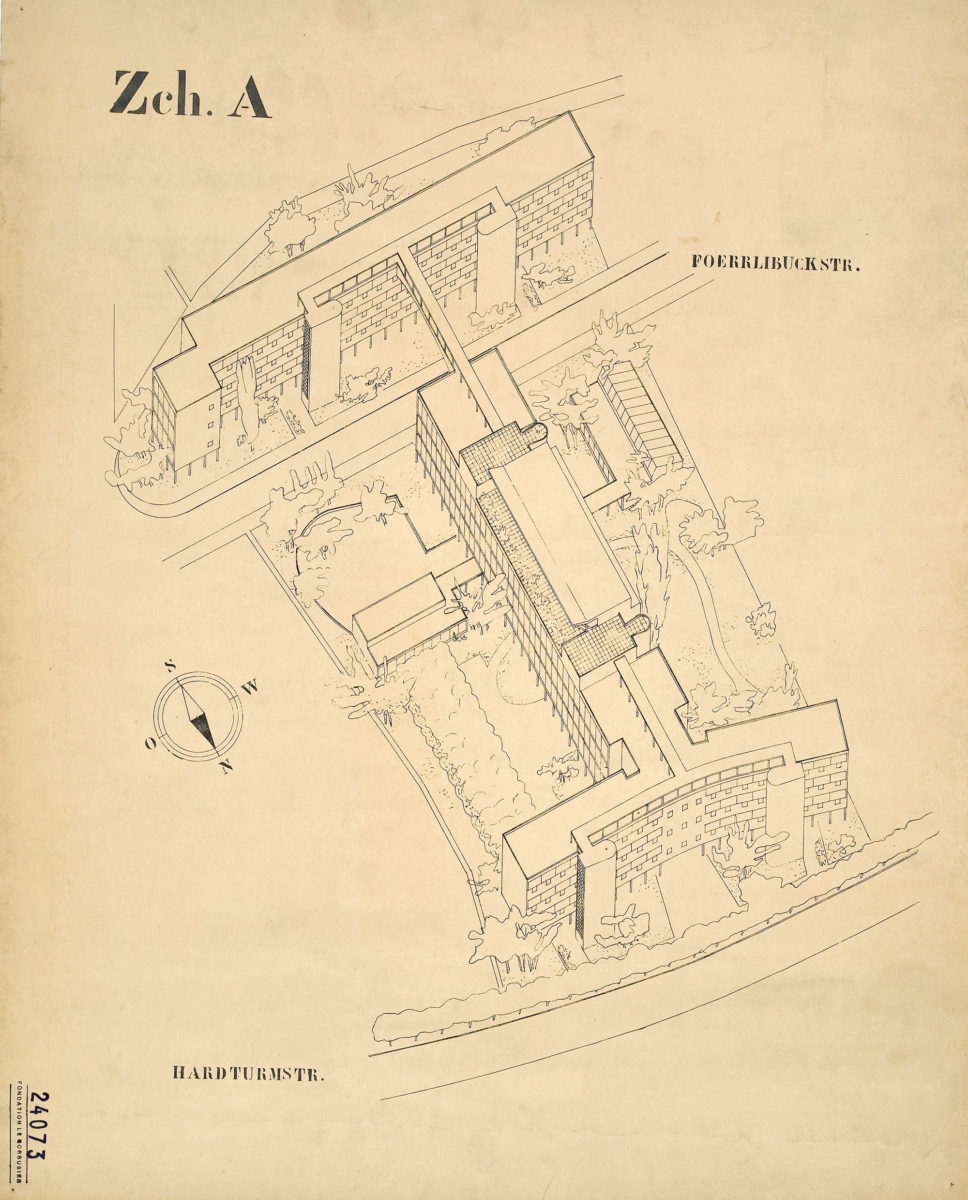

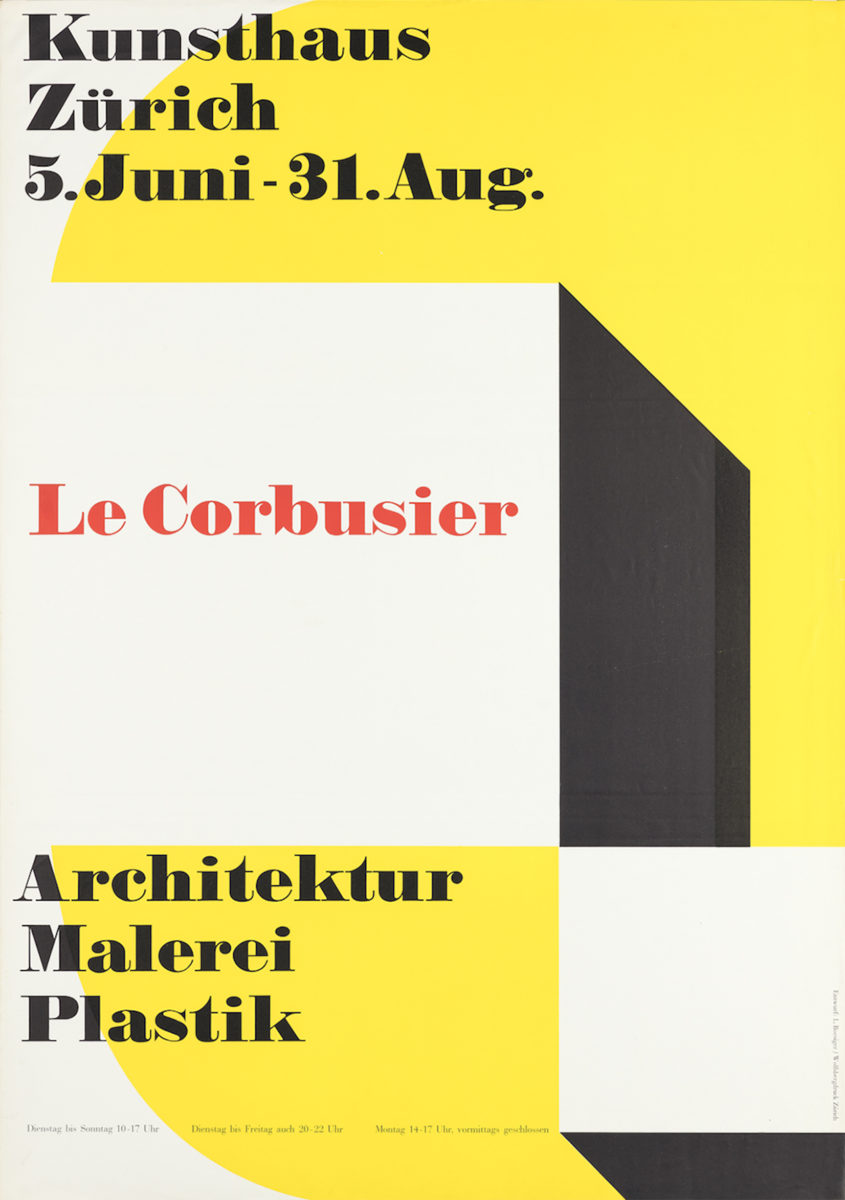

- Left to right: Left: Le Corbusier für das Kunsthaus Zürich: Le Corbusier Œuvre plastique 1917–1937. Tab- leaux et architecture,1938, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Plakatsammlung © Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris; Arbeiterhäuser Hardturmstrasse, Axonometrie, 1932, Zeichnung/Entwurf: Le Corbusier und Pierre Jeanneret, © Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris; Lily Boesiger für das Kunsthaus Zürich: Le Corbusier – Architektur Malerei Plastik, 1957, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Plakatsammlung

Where

Although it lacks the topographical drama of French-speaking rival Geneva, Zürich is easily the more architecturally beguiling of the two Swiss metropoles, combining a quaint old centre with thrilling ex-industrial fringes and lush green suburbs. Seefeld (prosaically translated as ‘lake field’), which stretches along the east side of Lake Zürich, is one of the latter. The pavilion is slightly set back from the waterside promenade, with views stretching across its lawn to the lake beyond. Nearby, boat rentals and swimming take place—the latter a favoured hobby of Corbusier himself, who died in 1965 while taking an ill-advised dip in the Mediterranean. Elsewhere in Zürich, the Museum für Gestalting itself is well worth a visit: one of Europe’s largest design museums, its collections are split between a 1930s modernist university building and Toni-Areal, a colossal 1970s brutalist yogurt factory.

“His architecture remains highly regarded, but he has become a recurrent bugbear for his impact on urban planning”

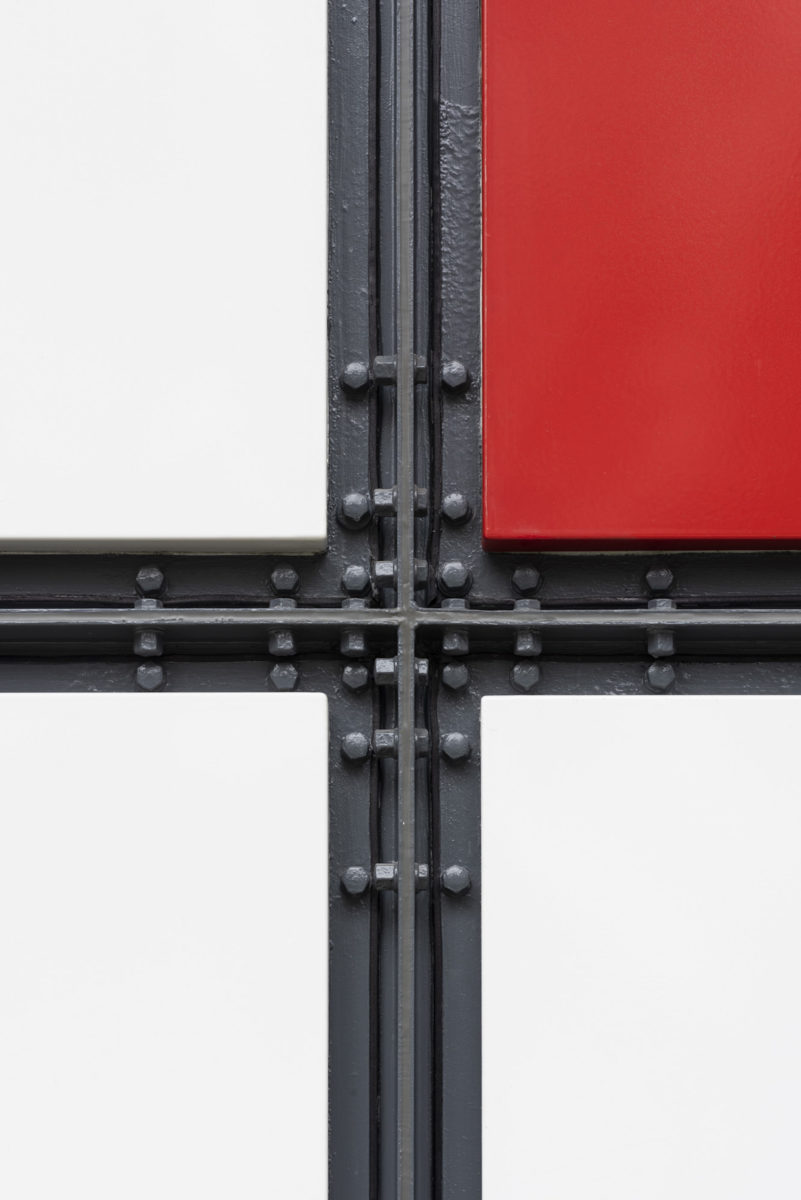

- Left to right: Leitungsführung (Gelb für Strom, Rot für Heisswasser, Blau für Regenwasser); Dachrinne; Fassadendetail. All Pavillon Le Corbusier, 2019, Zürich, © ZHdK

Why

Surprisingly, given his own love of art, Corbusier built only one museum, in Tokyo. The bulk of his work in Europe is residential and therefore off-limits to the public, including Marseille’s Unité d’Habitation concrete housing blocks and a host of private villas. The Pavilion Le Corbusier is therefore one of the few ways in which one can encounter a Corbusier masterpiece both inside and out (the others being his astonishing chapels at Ronchamp and Firmity, both in eastern France). For lovers of modern architecture, this is an essential visit.