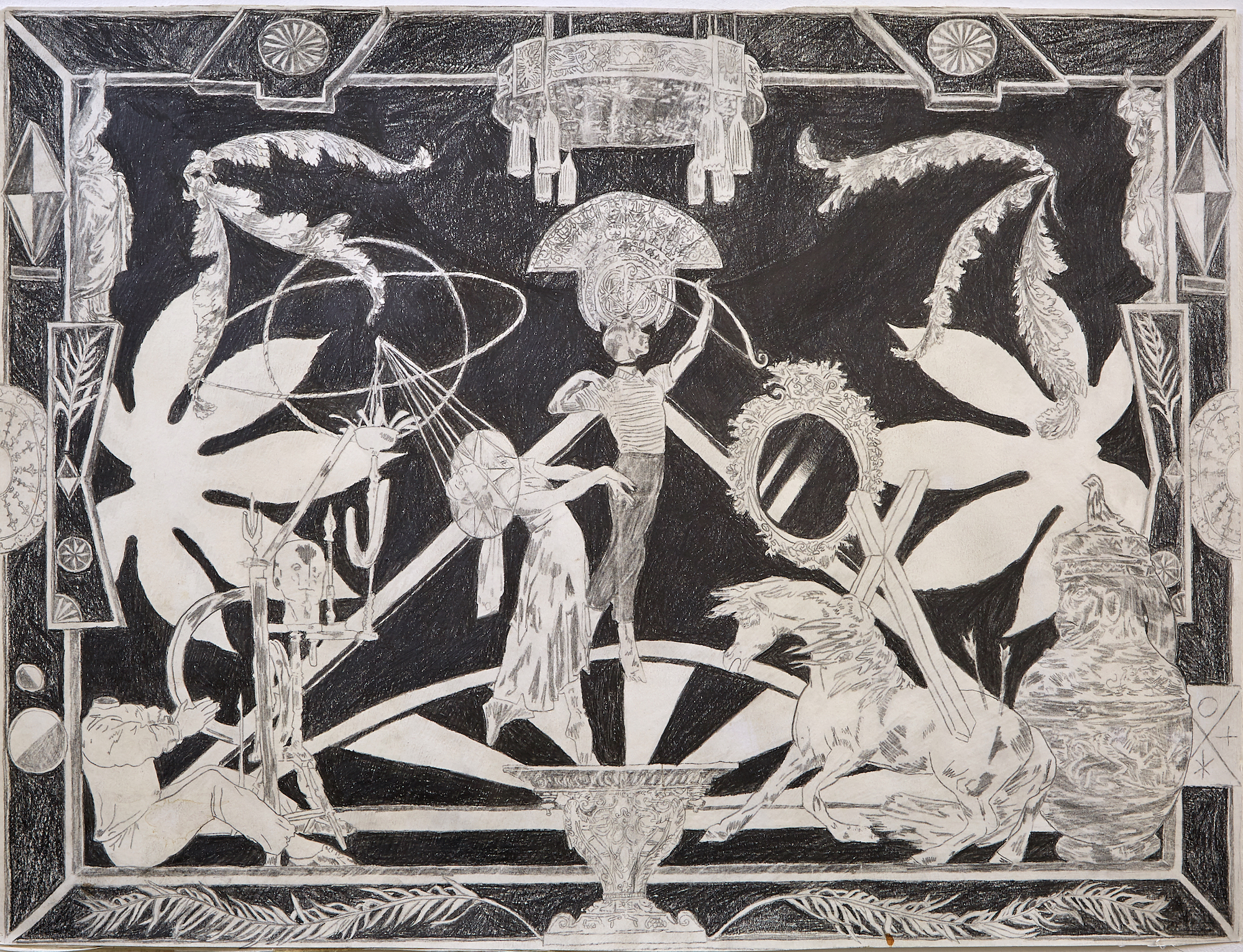

Do you ever feel like there are unseen forces, greater than ourselves, at work in the world? You’re not alone, with artists and writers from William Blake to Hilma af Klint speculating on the spiritual side of the universe. Beyond the devotional, the new technologies of the Internet age have given rise to a whole other set of invisible powers, from data mining to cyber security breaches. Mythologies both ancient and modern are taken up by artist Leo Robinson in his paintings, drawings, sculpture, video and collages. The nature of belief is at the heart of his surreal, folk-influenced works, dense with detail and freewheeling through symbols and signs.

Grids allude to pixels and nets, nodding to the growing, pervasive control of the online realm, while other forces at work are drawn into question, whether religious, philosophical or technological. Robinson is currently his first exhibition, Theories for Cosmic Joy, at Tiwani Contemporary in London; take a trip through the alchemical and the astrological.

How did you develop your interest in mythology, belief systems and spirituality, and what do you see as their relevance in today’s Internet age?

My interest in spirituality began six or seven years ago. I started reading beat poets and writers but particularly those with interests in Buddhism, people like Gary Snyder and Alan Watts, and then Dharma Bums and all that classic teenager stuff. But that got me into meditation in quite a serious way. I would date this as the beginning of the second chapter of my life, really. This is the same time that I also began taking art seriously, and taking nature seriously and taking folklore seriously.

Although the reference to “belief systems” in my recent work might seem like something academic and studied, they more stem from this meditation and the close study of my own impulses and tendencies and habits. For example, if I examine my own thoughts or desires, I might find that I have this impulse to turn my back on the modern world and go and forage for food and sleep in a cave and worship the soil, something extreme like that, and so in a painting this emerges as a civilization that eats bugs as a sacred practice, formed from the ashes of burnt machines. So the mythology is formed often in this way rather than through any deliberate research.

“The Internet appears throughout the work as a force, as a physical surface of nets or pixels”

Sometimes I do stumble upon aspects of art history or philosophy that really connects with what I find within myself. William Blake’s Newton, for example, is an image that I reference a couple of times in my most recent body of work. It is essentially a criticism of the scientific enlightenment of the seventeenth century, and I like it because it presents this kind of battle between two mindsets—Blake’s esoteric, prophetic mysticism and Newton’s calculated rationality and devotion to information.

And that brings me to the Internet part of your question. The Internet (within the wider sphere of technology, rationality and abstract thought) appears throughout the work as a force, as a physical surface of nets or pixels, constantly met with opposition from the anarchic or the divine. So I guess the work is a way of reconciling these two opposing forces, finding a way that they can exist in harmony.

What influences the look and style of your work, which has a timeless, almost naïve quality to it?

I would say my primary interest when creating images is magic. So when I’m creating a composition or choosing colours there’s always a kind of alchemy at work or a reliance on an instinct that comes from somewhere outside of the self. A lot of my inspirations for the work are artists who I feel don’t create only pieces of art but magic spells. Some examples are Hilma af Klint, Walt Whitman, John Coltrane, Hieronymus Bosch…

Also, of course, the forms that exist throughout the world’s religious art are borrowed and repurposed a lot in my work, as well as the alchemic and astrological. All the stuff that is reaching for transcendence. And I guess that’s where the timelessness comes from, aiming towards something all-encompassing or universal. There’s definitely a nice irony in making work that is almost cynical towards the search for transcendence whilst simultaneously acting as just that. I find it inescapable.

“When I’m creating a composition or choosing colours there’s always a kind of alchemy at work”

I think I’ve been slightly avoiding answering your question up until now, only because I find it so difficult to pin down where my stylistic influences are, outside of a few obvious prophetic figures such as Bosch, Blake and also Henry Darger, whose approach to composition and colour and narrative contained so much magic and depth. It’s interesting that he is spoken of as naïve also, despite showing a total mastery of the techniques he used. But for me it’s mostly a process of absorbing a lot of images and experiences and letting them stir in the back of my mind until they’re ready to emerge in the work.

Who are the figures that appear in your work, and how much of a narrative do you build and imagine around them when composing these paintings?

Very few of the figures are individual characters with personalities but rather representatives of the actions of the mind. They are often shown in a state of transition between one extreme and another, for example they may be cleansing themselves of their idols or machines, and through this achieving an Eden-like purity; or destroying the natural environment to achieve a kind of technological utopia; or separating themselves from their physical bodies to enter a purely abstract and informational existence. The figures really act as tools for mapping the mind.

The overall narrative has continued to build through the making of the work, to the point where it has a few recognisable locations. The same mountain, with a cleansing beam of light shining down on its peak, appears in three separate works as the site of various conflicts taking place at different times. The machines I create also constantly reappear and rearrange themselves.

“The figures act as tools for mapping the mind”

The only real reoccurring character is the horse, specifically a deity I call Horse Christ, which is almost omnipresent throughout. I think what draws me to the horse as a character is that it is so present in art from all over the world, yet it is rarely the subject of heroism or conflict or judgment, it is simply present, and this is how it acts within these compositions. It is the only character who is not yearning or reaching or trying to renew itself, and so represents what’s really at the heart of the pieces, which is non-indulgence in ideals and absolutes.