“I have always treated myself as a found object,” says British artist and musician Linder Sterling. Born in Liverpool in 1954, Linder grew up in Manchester (befriending fellow outsider Morrissey) and has impeccable punk pedigree. She made “menstrual jewellery” from broken coat hangers and lint tinted red and, during a performance with her art-punk band Ludus, wore a dress made of discarded chicken parts from a nearby restaurant, ripping it off at the show’s climax to reveal a shiny black strap-on dildo. While studying graphic design in the 1970s, she soon abandoned the pen in favour of the scalpel to make subversive photomontages, including the cover art for The Buzzcocks’ 1977 single Orgasm Addict, which showed a naked woman with grinning mouths for breasts and an iron for a face.

That was the era when Linder began to call herself a “monteur”, and this latest retrospective of her work at Nottingham Contemporary, spanning more than forty years of photomontage, graphics, costume and performance, is among other things a masterly (or perhaps mistressly) demonstration of the artist’s talent for collage and juxtaposition. Just as in her own graphic art Linder talks of “performing cultural post-mortems and then reassembling the corpses badly, like a Mary Shelley trying to breathe life into the monster”, she has brought together in this show a rich constellation of other influential imagery, weaving it with her own into suggestive patterns.

The show is divided into four parts—The House of the Future, The House of Rest, The House of Unrest and The Abode of Sound—in which the idea of home is staged, respectively, in relation to performance, to spectres and mourning, to surrealism and political agitation, and to living with sound. Among other highly original parallels, Linder draws a line between architects Alison and Peter Smithson’s 1956 design for “the house of the future” at the Daily Mail Ideal Home Show (where actors dressed in futuristic costumes performed a scripted dialogue) and seventeenth-century court masques.

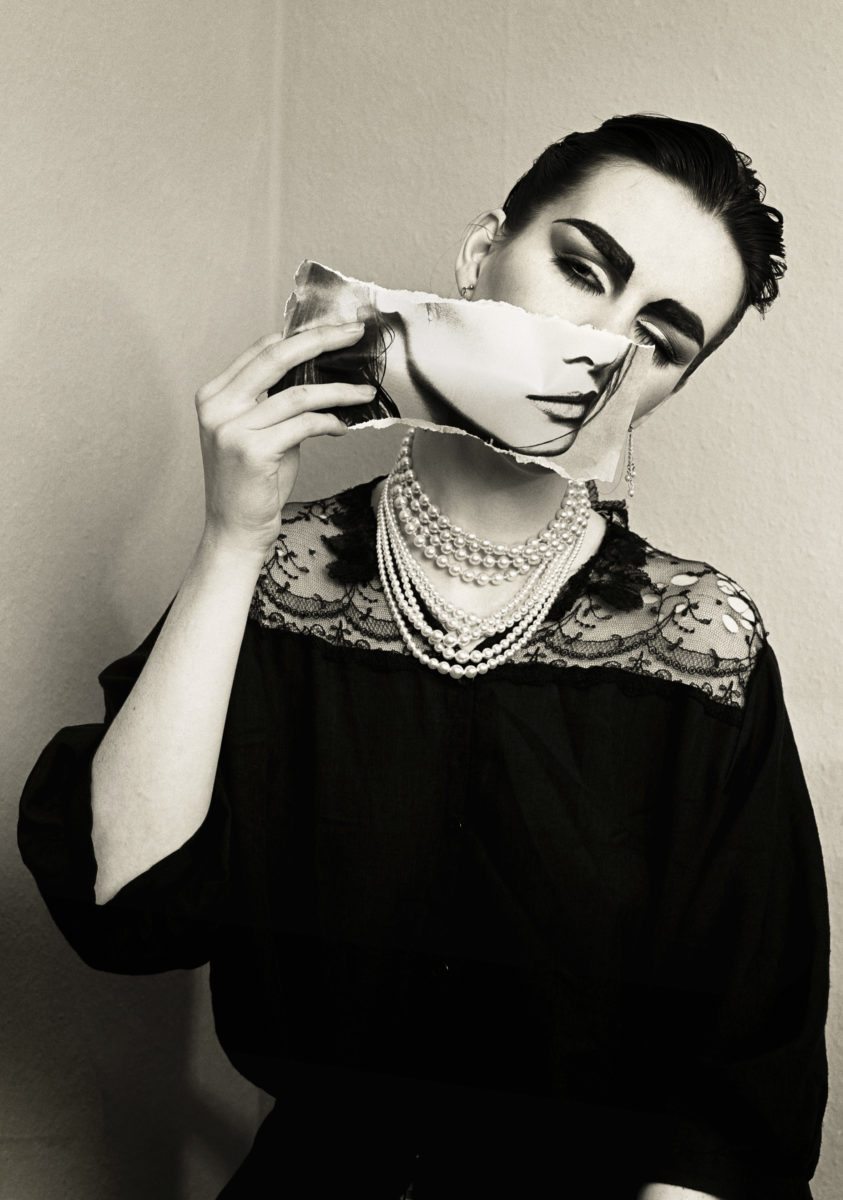

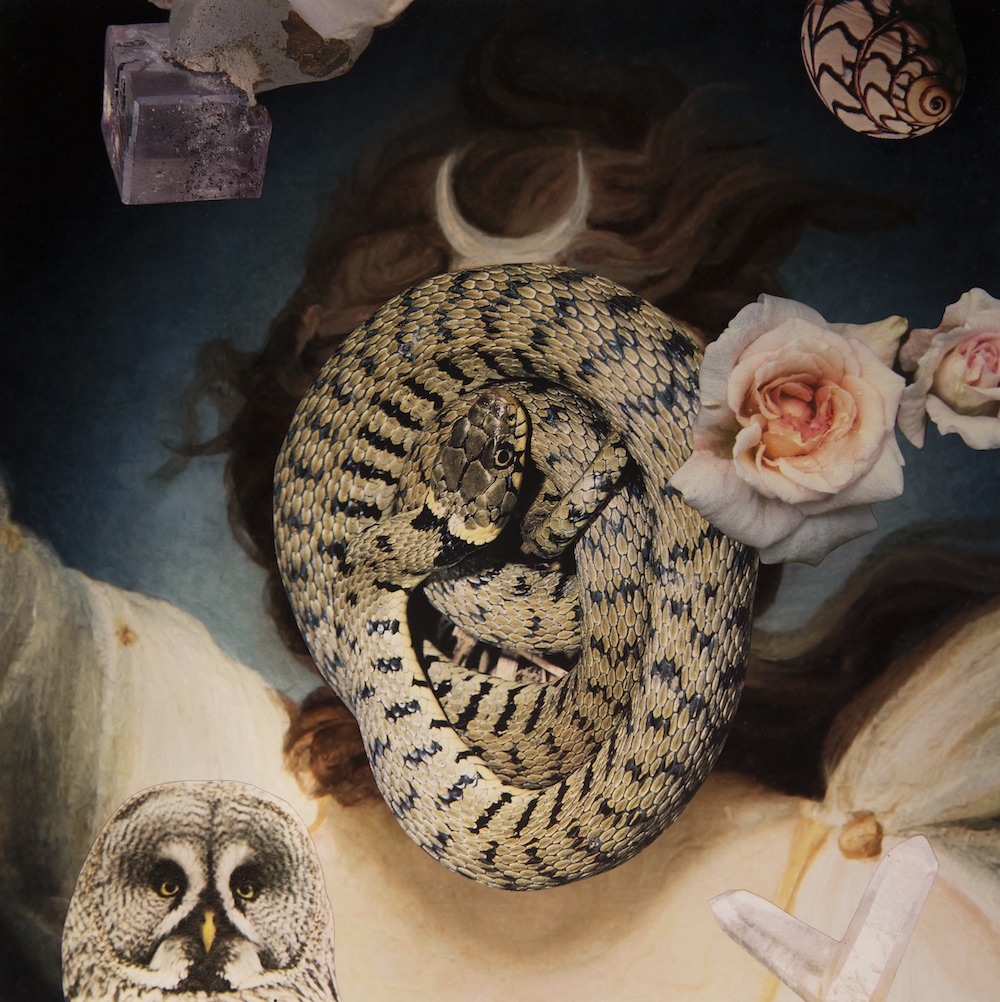

A central motif of the show is lace, whose industry is historically associated with Nottingham, and which Linder describes as “an intricate weave within a grid, a form for decorative movement or sound”. Thus, lace features in beautiful 1860s photographs taken for the V&A (then the South Kensington) Museum by Isabel Cowper, possibly the first official female museum photographer, and in Linder’s own “lingerie masks”, as well as in artist Mike Kelley

’s Ectoplasm works and in a series of séance pictures featuring mediums in a trance—though in the last two cases it has been used, unnervingly, to make ectoplasmic gunk. The exhibition also revives the work of little-known or overlooked female artists: there are for example some wonderfully uncanny surreal photomontages and photographs of society women masquerading as goddesses made in the 1930s by Madame Yevonde, and strange paintings by the surrealist Ithell Colquhoun, who was expelled from the surrealist group because of her interest in the occult.

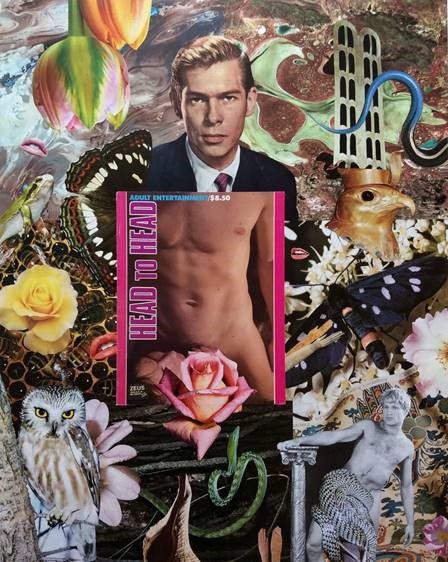

- Linder, Untitled (Johnny Ray), 2017

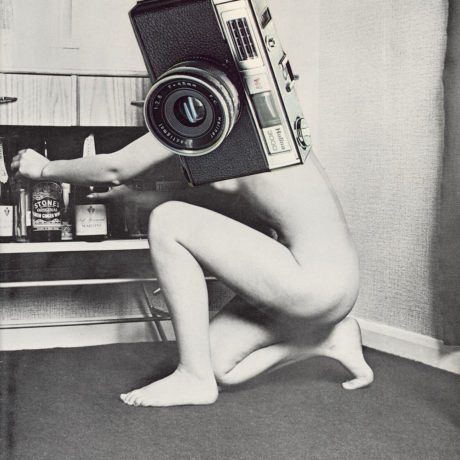

- Linder, What I Do To Please You I Do, 1981-2008. Courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art, Dependance, Andrehn Schiptjenko, Blum & Poe

Linder is currently (the first ever) artist-in-residence at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, which she describes as a kind of “sensorium”, and the exhibition also grew out of her delving into the Devonshires’ collection and family history. Objects she borrowed include Victorian memento mori, hair jewellery and geological models made of marquetry; works she made at Chatsworth revolve with fascination around the figure of Elvis (of whom Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, was a fan). Linder has always been interested in moments when “the veil between worlds become thin”. With its wealth of imagery and Cocteau-style gateways to and from the afterlife, The House of Fame brings together many different worlds into one: Linderland.

In issue 34, Linder discusses some of the key works in the show. You can buy a copy here.