It has been fifty years since the decriminalization of homosexuality in Britain, a victory that has been celebrated up and down the country since the beginning of the year. The Sexual Offences Act reversed archaic laws that had forbidden sex between men since the Tudor era and was certainly a step in the right direction, but a closer look at the legislation highlights the narrow-minded views of sexuality that permeated during the era and are still being dismantled to this day. For starters, the Act stipulated that men must be aged over twenty-one, be in a private space and not be serving in the armed forces. There was no mention of women at all, and the prescriptive ruling also led to other sexual acts being more vehemently prosecuted. Perhaps most shocking though, is the fact that the legislation only applied in England and Wales, with Scotland and Northern Ireland failing to follow suit until the 1980s.

It is these chasms of history that have informed the Walker Art Gallery’s survey exhibition Coming Out: Sexuality, Gender and Identity, born out of in-depth curatorial research conducted by Charlotte Keenan McDonald. “A lot of the work I have been doing to date is around LBGT+ history in the collection and the way that it has been erased,” she says. “I’ve been really interested in seeing what has been done in terms of research and who has been overlooked, as well as people who have been part of public histories.”

The idea of institutional erasure is something that many museums have tried to correct by presenting interventions or “alternate” displays that engage with concepts sidelined in the art historical canon. However, these are often temporary interjections that rely on another singular narrative, which doesn’t leave much room to move beyond traditional sexual binaries. With that in mind the Walker has placed an emphasis on plurality, eschewing a didactic, chronological approach for fluidity, encouraging dialogue (with an active, ongoing events programme conducted in the FORUM space) and drawing links between seemingly disparate practices.

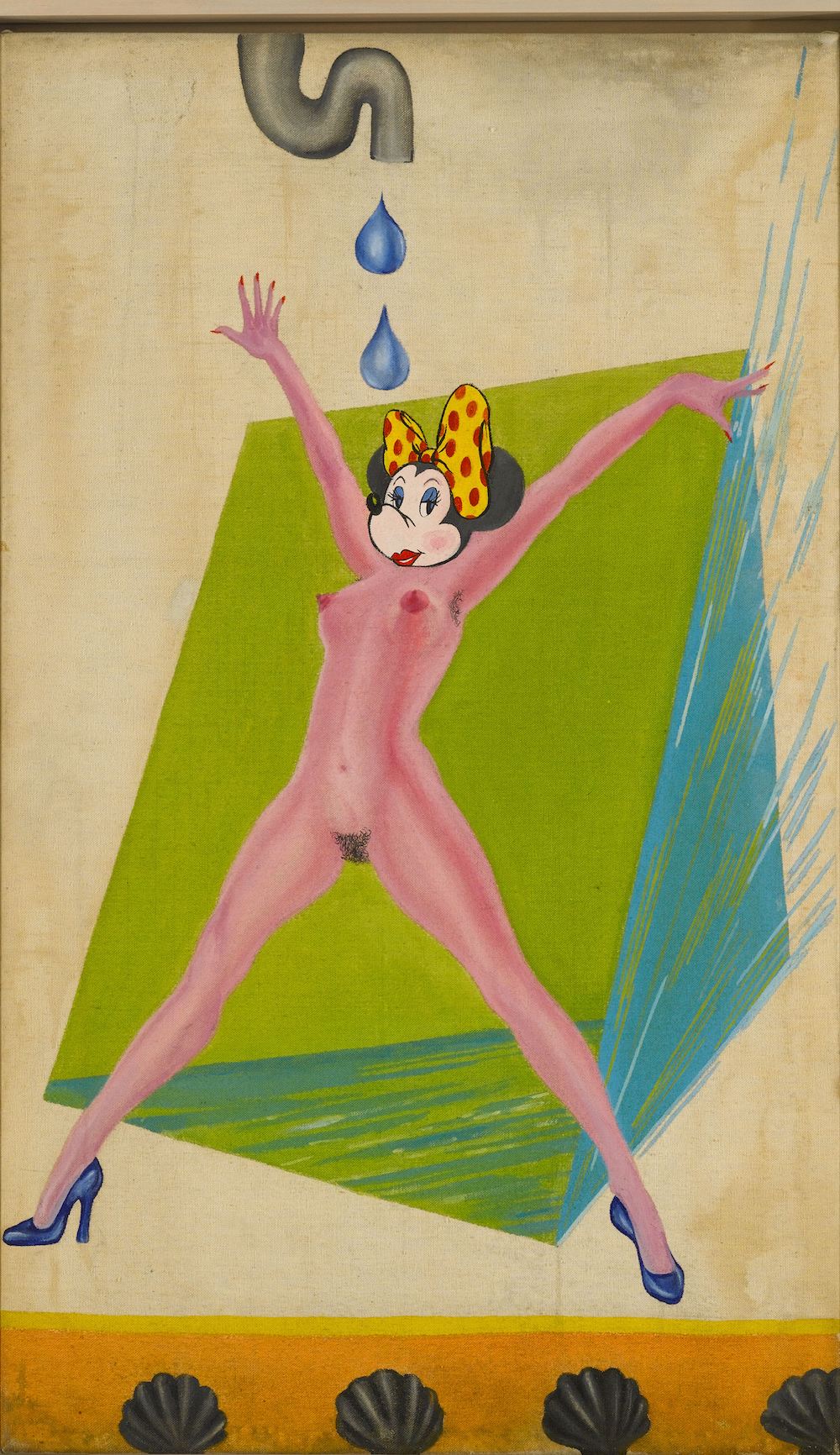

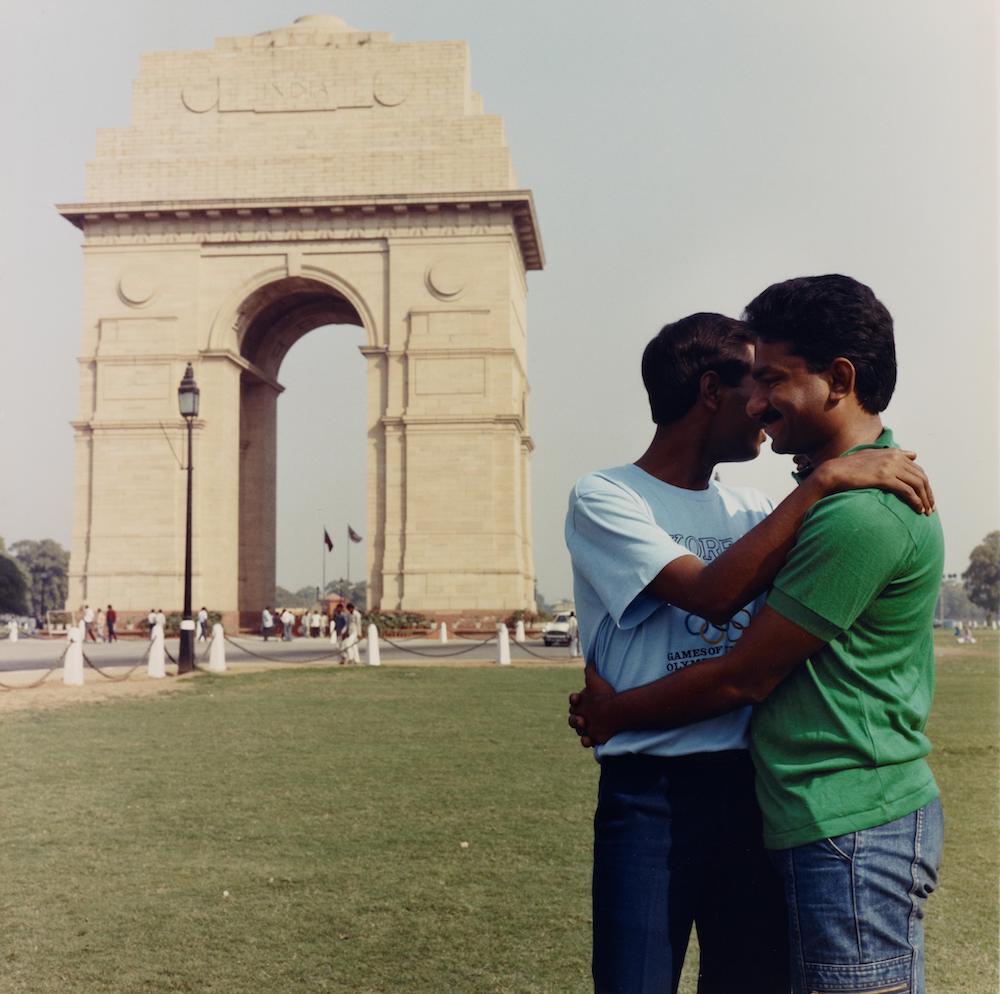

The notion of grouping artists based purely on sexual identity is also fraught with tension, so the Walker’s raison d’être has been to present individuals who actively explore these themes in their work. The premise is a strong one and demonstrates the myriad ways that personal experiences and more overarching socio-political concerns interact. In the first gallery this form of introspective progression is shown in two comparative David Hockney paintings. His earlier piece We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961) presents an intimate, thinly veiled embrace between two men. A mere five years later he painted Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool (1966) which features a boldly eroticized naked male form–it is considered one of the artist’s most groundbreaking works.

The subtle beauty of male same sex intimacy is also explored in Steve McQueen’s silent video piece Bear (1993). The unusual and at times shocking camera angle records two naked men wrestling from below, capturing a flirtatious and sensual embrace that straddles violence and desire. The subject also makes reference to the common use of wrestling poses as a nod to homoerotic interests in nineteenth-century art.

Focusing on a male-centric viewpoint is also an issue that queer communities have attempted to pull apart, and a refreshingly adequate space has been given over to other voices in this show. In recent years trans identity politics (and persecution) have come to the fore, but are still starkly underrepresented in mainstream visual culture. The Walker has admitted that addressing this glaring omission from the “LGBT” initialism was a challenge, but it has still managed to present some compelling and innovative forms of trans-focused art. For example, activist Charlie Craggs offers free manicures as part of her project Nail Transphobia throughout the show’s run. This new enterprise allows people to ask her about her experience as a trans woman while getting their nails done.

The inclusion of Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz’s video piece I Want also goes further to redresses the imbalance. The duo often recall moments in queer art history in their work, and this piece marries a seventies monologue by punk poet Kathy Acker with an interview transcript from American whistleblower and trans woman Chelsea Manning.

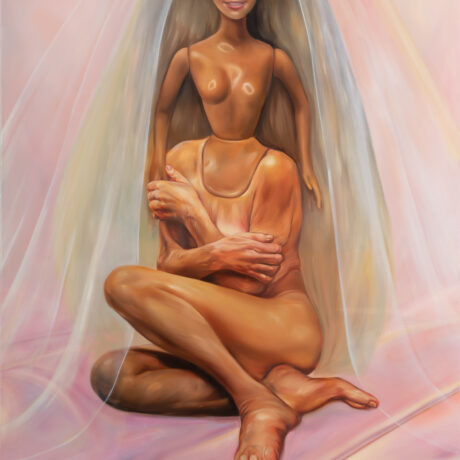

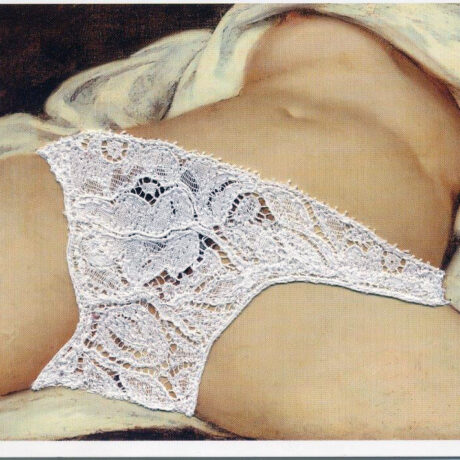

This intersection between personal revelations and a globally-reported military scandal once again cements the refrain that “the personal is political”, as well as reminding us of the most aggressive forms of censorship and oppression that exist as part of the tangled web that is LGBT subjugation. Zanele Muholi continues to remind us about the repressive notions of female beauty and sexuality with her photographic Miss Lesbian series (2009). These self-portraits show her in pageant girl clothing, but with natural body hair and a sash reading “Miss Black Lesbian”. Shockingly the image itself was airbrushed by Transport for London when it was used in an advert for Mojisola Adebayo’s 2013 play I Stand Corrected. The hair on her bikini line was removed on the grounds of vulgarity, which demonstrates how women’s bodies continue to be policed.

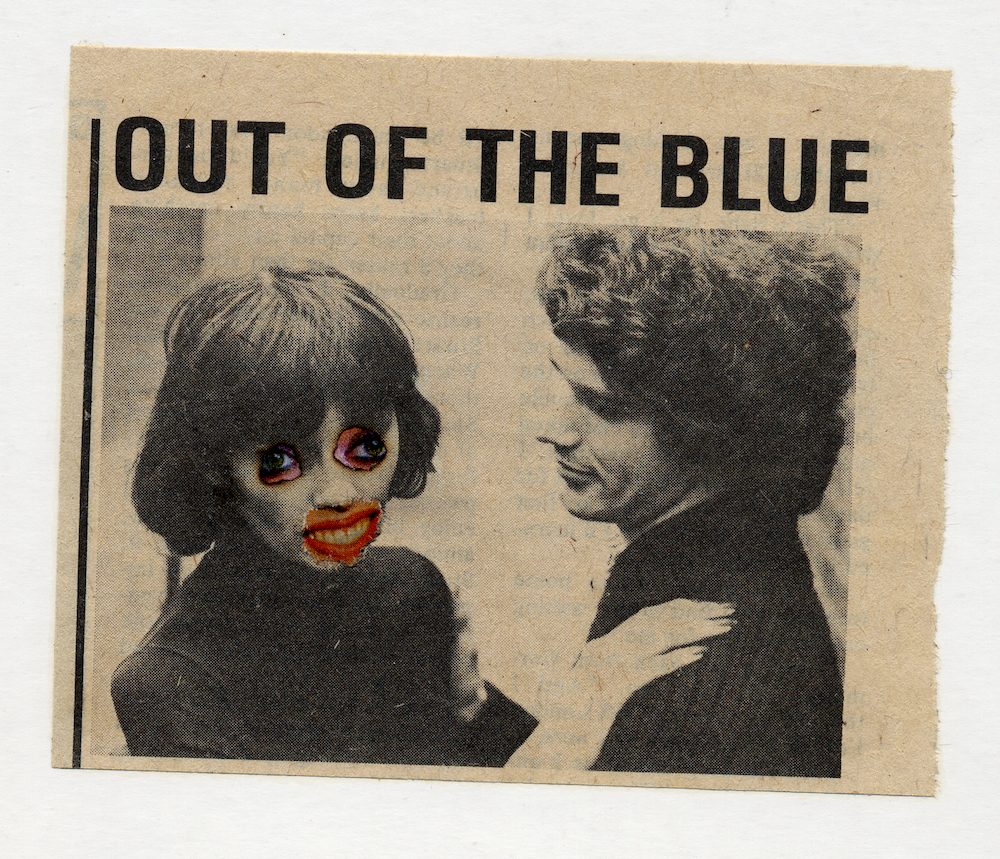

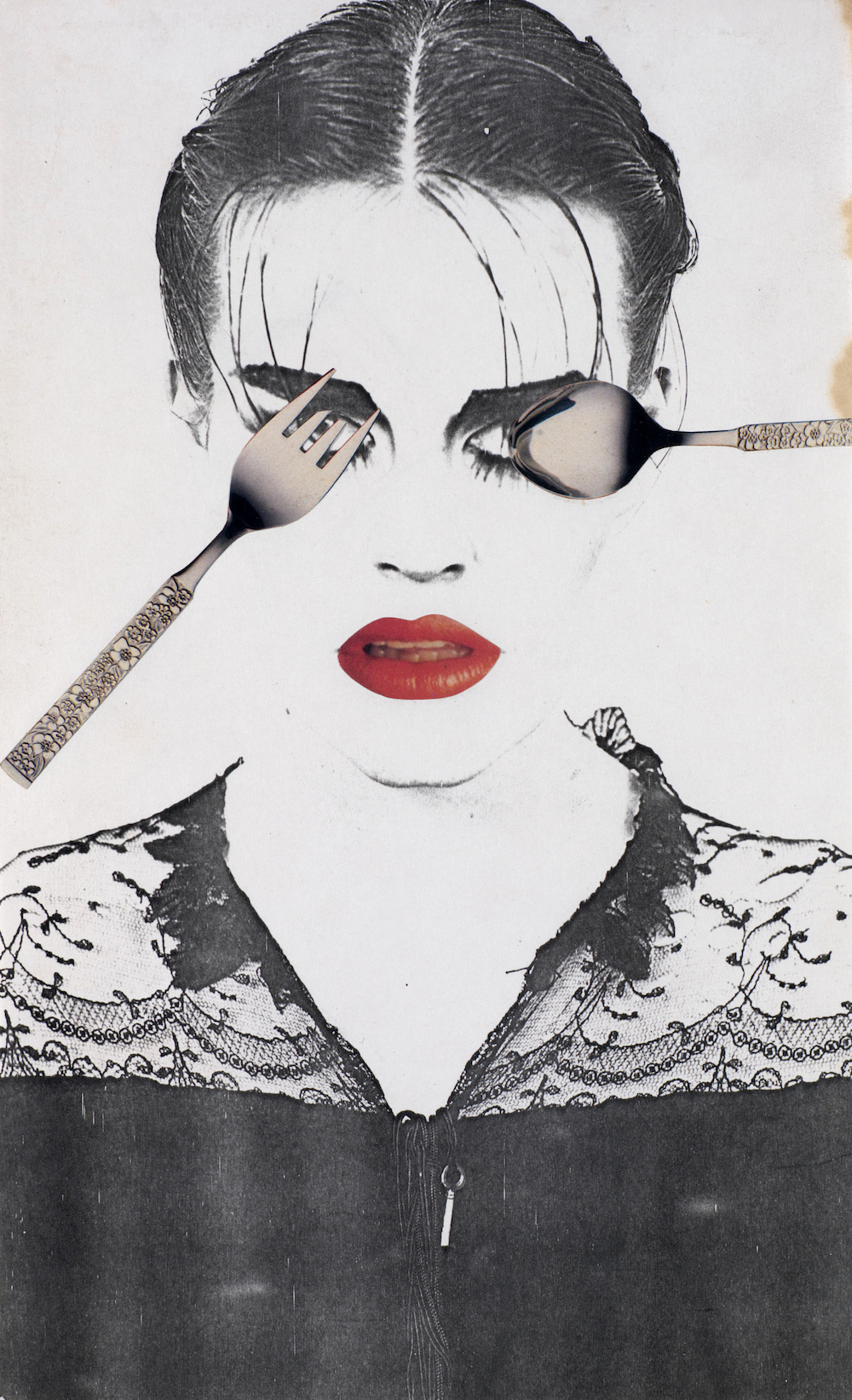

These small, disturbing revelations highlighted throughout the show help to piece together lived experiences that many of us might not have witnessed first hand. Karen Knorr’s revelatory photographs take place at the opposite end of the spectrum by recording the thoughts and actions held by Britain’s ruling class. The problematic attitudes towards women and anyone not associated with the higher echelons of government are vilified, and the unease is magnified as her portraits are taken in exclusive male-only members’ clubs.

Knorr’s meditative black-and-white portraits could not be further from the explosion of colour, sound and performance that closes the exhibition. This bombastic, large-scale installation titled Alien Sex Club (2015) is the work of John Walter, an artist who is dedicated to raising awareness around HIV/Aids. By creating a queer space with adequate, important information around sexual health (including the availability of the groundbreaking preventative drug PrEP) Walter connects art and activism in an exciting and relevant way.

This innovative immersive piece is one of several that have been acquired for the Walker thanks to an Art Fund grant and is the first performance work to enter the collection. McDonald hopes that this will mark a turning point in the gallery’s policies and also act as a catalyst for further research and public engagement. As she mentions, “Really it’s all about how we understand issues around LGBT+ communities and histories, to give voice to artists who have always had to fight for their own spaces.”

“Coming Out: Sexuality, Gender and Identity” shows until 5 November at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. liverpoolmuseums.org.uk