Lisetta Carmi is best known for a photo essay titled I Travestiti, shot in the late 1960s and early 1970s in Genoa, comprising humanising portraits of the trans community living in a disenfranchised district of the city. In the context of Italy’s traditional, religious society at the time, the portraits constituted a political act, but they also became a profoundly personal exploration that Carmi reflected “made me ponder over the right that we all have to determine our own identity”. I Travestiti remains an important part of Italian cultural history, presenting bodies, sexuality and gender.

As a chronicler of contemporary life, Carmi, who is now 96, has been consistently preoccupied with the stuff that makes us human. Years before she started to work on I Travestiti, she undertook a commission documenting various hospitals in Genoa that would lead her directly to the source of humankind, to the most universal, fundamental, and heavily censored of subjects: birth.

“Carmi and her camera are simply witness to the physical endurance and triumph of a female body”

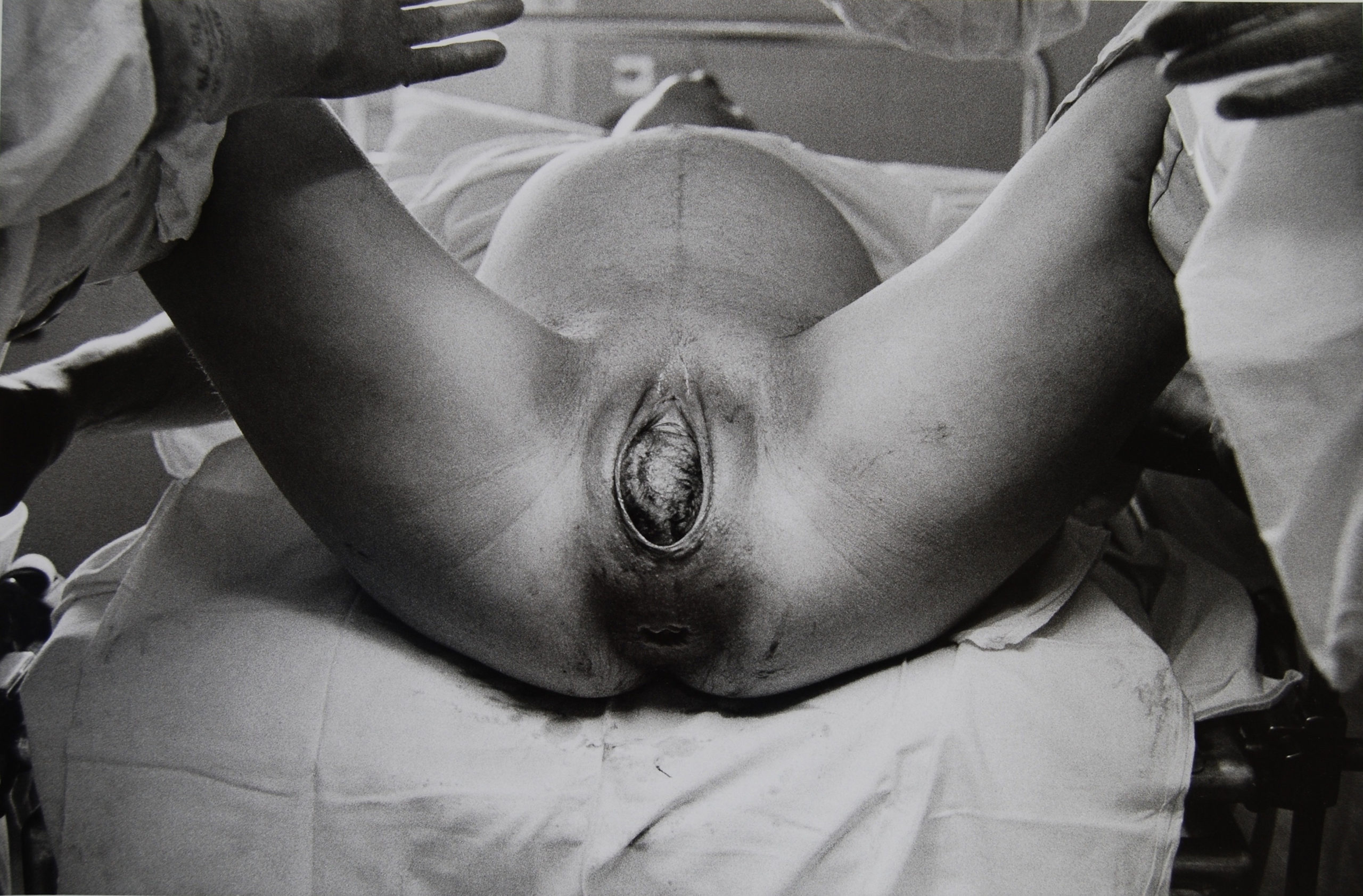

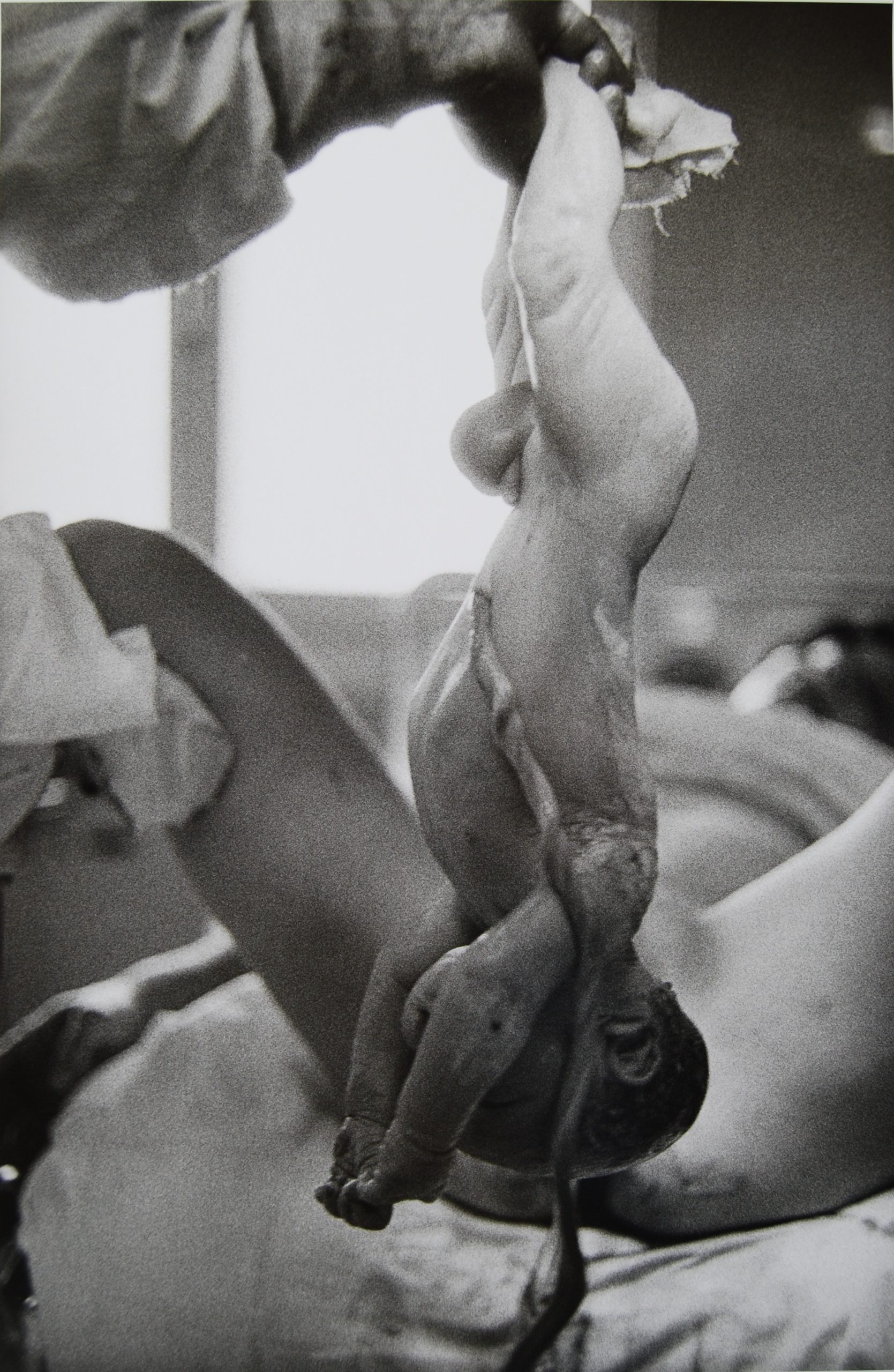

Originally produced as part of this wider commission, Il Parto documents the birthing process in eight pictures. On 19 October 1965, Carmi attended a birth, and the resulting series of eight photographs, likely shot on a Leica 24×36, demystifies the experience. The artist decided to frame the mother’s legs and vagina close enough to observe in detail from the point of crowning, to the emergence of the head and, finally, a new body: a baby boy.

This full-frontal viewpoint is a radical reinvention of the image of birth, confronting the viewer and leaving nothing to the imagination. Carmi and her camera are simply witness to the physical endurance and triumph of a female body. Interestingly however, at the time, there was no need to request permission to photograph a birth from the mother: Carmi recalls it was a young woman, but her name and story is unclear.

- © Archivio Lisetta Carmi e Martini & Ronchetti, Genova

The photographs were mostly used in an educational context; they were presented during lectures at universities, for example. They demonstrate the birthing practices of the day: the mother lies on her back, a common position for hospital deliveries at the time, but not necessarily best for the woman. White coats and the gloved hands of medics enter only the edges of frame, aiding the safe delivery of the newborn, and appearing to reassure the mother; the chaos and pain is silenced by the static picture. We see fluids and blood, the labour of birth. We can only imagine how Carmi herself felt as she watched; she ensures an unobstructed view but we cannot see the mother’s reaction, or that of the people who surround her.

The final picture presents the baby on a table, not in its mother’s arms. There is a scientific interest in the eight photographs, but they also constitute an exceptional and rare document of the body. Given Carmi’s continued interest in countering the narrative around the role of women in Italy, the pictures oppose the prevalent image of the “donna angelicata” and the Madonna, celebrating motherhood in a way it hadn’t ever been portrayed in visual culture, even in a medical context.

Il Parto hardly received any attention in the form of exhibitions, either in Italy or abroad; it is not known what the hospital used the images for after they were taken, either, but now the entire series is exhibited as part of the 2020 Rome Quadriennale, exposing it to a larger audience and positioning the importance of these images in a much wider cultural sphere. “I am sure the hospital did not expect to end up with these kind of images, that Carmi took very freely, taking advantage of the freedom she had to move around the hospital,” explains Sarah Cosulich, co-curator and artistic director of the Quadrenniale. “Lisetta just went into the room—a proof of how daring and unexpected her gaze was.”

Far from being limited to the informational or instructional, the scope of these pictures is significant; they are still, decades on, astounding in their directness and shock only because we are not used to seeing women’s bodies, or birth, exposed in this way, and presented with such candour and detail. If we look away, we have to ask: Why? Il Parto offers a glimpse into something that connects us all above and beyond culture: the magic of being born.