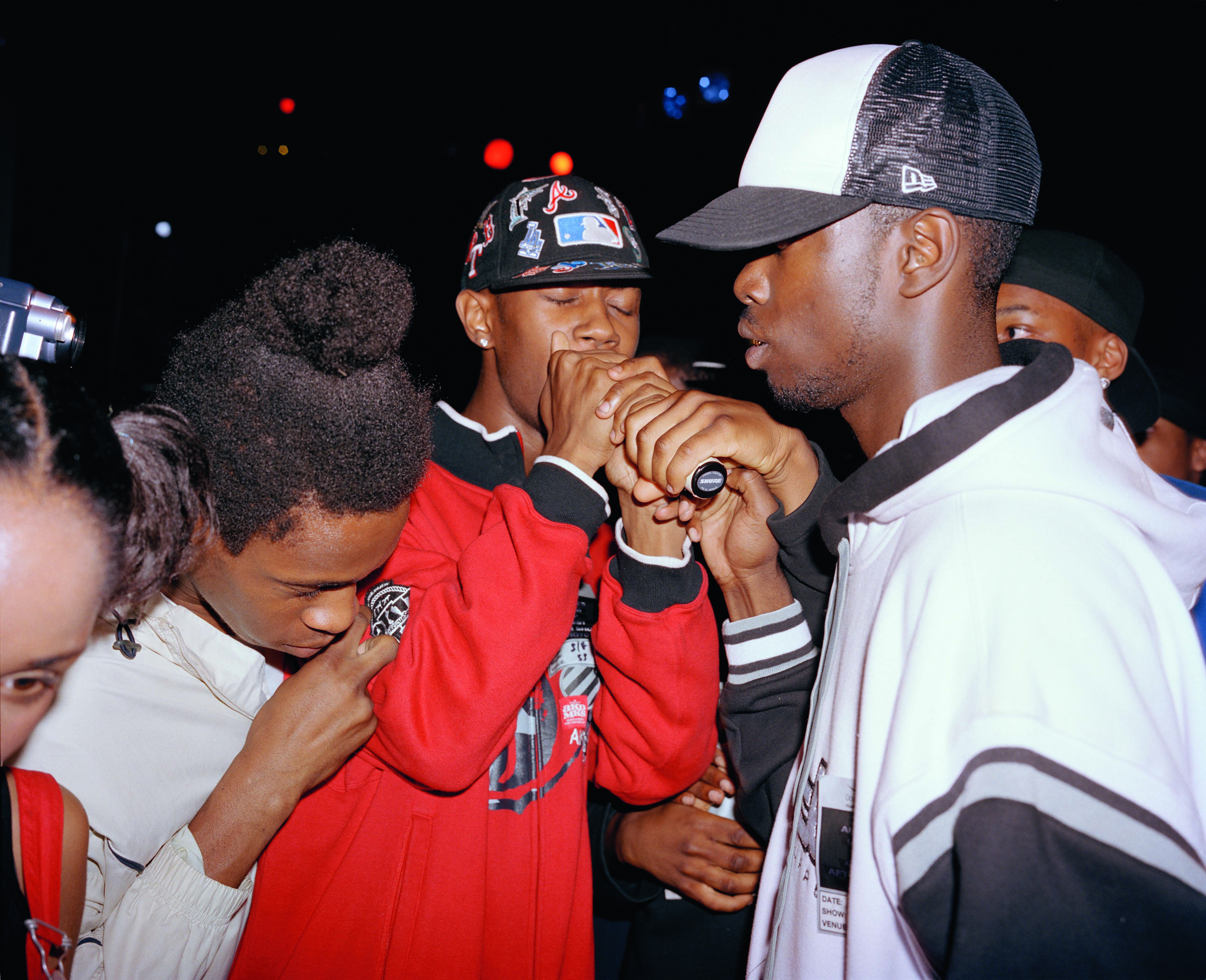

“I have to turn something negative into something positive,” says Liz Johnson Artur, speaking on the phone from her studio in South London, where she is busy preparing the final new works for her first major solo exhibition. The analogue-only photographer is talking about her method, but it also serves as a beautiful metaphor for what she does: documenting strangers and friends, in flux and flowing all over the globe, coming together, celebrating, loving, living life. The fiity-five-year-old artist was born in Bulgaria to a Russian mother and Ghanaian father, and spent a lot of time on the move until she settled in the UK—one of the reasons she first turned to photography in the mid-eighties, was as a way of connecting with others. Though she has been working in commercial photography for more than thirty years, and has toured with the likes of Lady Gaga and M.I.A, she has kept her deeply personal artistic practice separate and under wraps. Mostly shot in South London—where she has lived since 1991—on 13 June the artist will finally reveal her Black Balloon Archive, comprising hundreds of photographs of black communities and diasporic life, to the general public in a rare exhibition, in the neighbourhood in which it was made.

- Left: Burgess Park, 2010; Right: Elephant and Castle, 1991

This exhibition at South London Gallery feels, in a way, like a homecoming for your Black Balloon Archive. Why now?

I’ve been doing what I do for a long time. I’m based in Peckham and I’ve known the gallery since I moved here, twenty-six years ago. It’s a place I felt was accessible to the people who I want to see the work, but I also felt that the gallery should represent more of what’s surrounding it. I had never seen a connection with what they were showing and what I was seeing on the streets. That’s not meant as a criticism, that’s how it’s run. I haven’t been working undercover but until I exhibited at the Berlin Biennale last year my work never got much attention, a lot of curators saw it there for the first time. Let’s put it this way: I think if I had approached the gallery in the 1990s, I doubt I would have been given the space. I’m not accusing, I’m just observing. Times are changing.

You’re presenting the photographs in different ways at SLG, using different materials—you’ve got bamboo, textiles, etc…

I see my work as a backdrop to the things that can happen there. I wanted to present my work in an installation-based way, to move away from traditional printing and framing, and to use the space on different levels. Spaces can tell stories. I’ve only started showing my work since my book came out in 2016, and until then, I’ve been living with it, accumulating it and making sense of it. It’s been an exploration. I wanted to use all kinds of materials because that’s how I live with the work, I’m quite tactile in my approach, most of my work exists in sketch or workbook form. With the very traditional training I have, it was all about achieving the perfect print, which I love, but I’ve not always been able to do what I want with photography. I like to have the precious exist with unprecious things. So for me presenting one nice archive photograph wouldn’t represent what I do and why. I want people to get a sense of that.

I came across your work in 2016 when your book came out, and when you were included in Ekow Eshun’s exhibition on Black Dandies. Why has it been important for you to focus on the Black Balloon Archive for so long without showing it in public?

I see it as a luxury that I’ve been able to work out of sight, that I didn’t have a financial need and that I could dedicate myself to it, for no purpose other than my own. I’ve been good at keeping it separate to my freelance work. I wanted to make these photographs for myself, they’re part of my life, and I would never have been able to accumulate them if there was some kind of demand. They had to come out of the rhythm that’s embedded in life.

I guess being able to sit with the work for so long and really understand it is also important when you’re creating an archive?

It is because I’ve been doing it on my own terms that I had to see what my moral obligations are. I approach strangers, the archive is full of people, and they trust me to treat their picture right. If someone approaches me to photograph me on the street I’m skeptical, because I know behind the camera too well. I have a responsibility, if I ask someone for a picture, not to abuse or misuse that picture. You are in a power position as a photographer, and if I’m telling someone bullshit I have to live with that. A photograph can take many lives. Where, what and why I do what I do, is because I have received respect and dignity, and I want to preserve that and treat it accordingly.

How has photography impacted your life?

When I was at the Royal College—I enrolled just after I arrived in London—the first lecture I attended was titled the Death of Photography. Digital wasn’t even in the picture, but we were discussing street photography in the 1960s. I thought it was ridiculous because I believe we should engage with each other—what’s missing is respect for the moment. We don’t need to declare that photography is dead—we need to be able to question how to treat the photographic act and the people we photograph. When I discovered photography, I literally discovered a tool for approaching other people. I have learned a lot, and it has definitely changed how I relate to people.

Liz Johnson Artur: If You Know the Beginning, the End Is No Trouble

From 14 June to 1 September at South London Gallery

VISIT WEBSITE