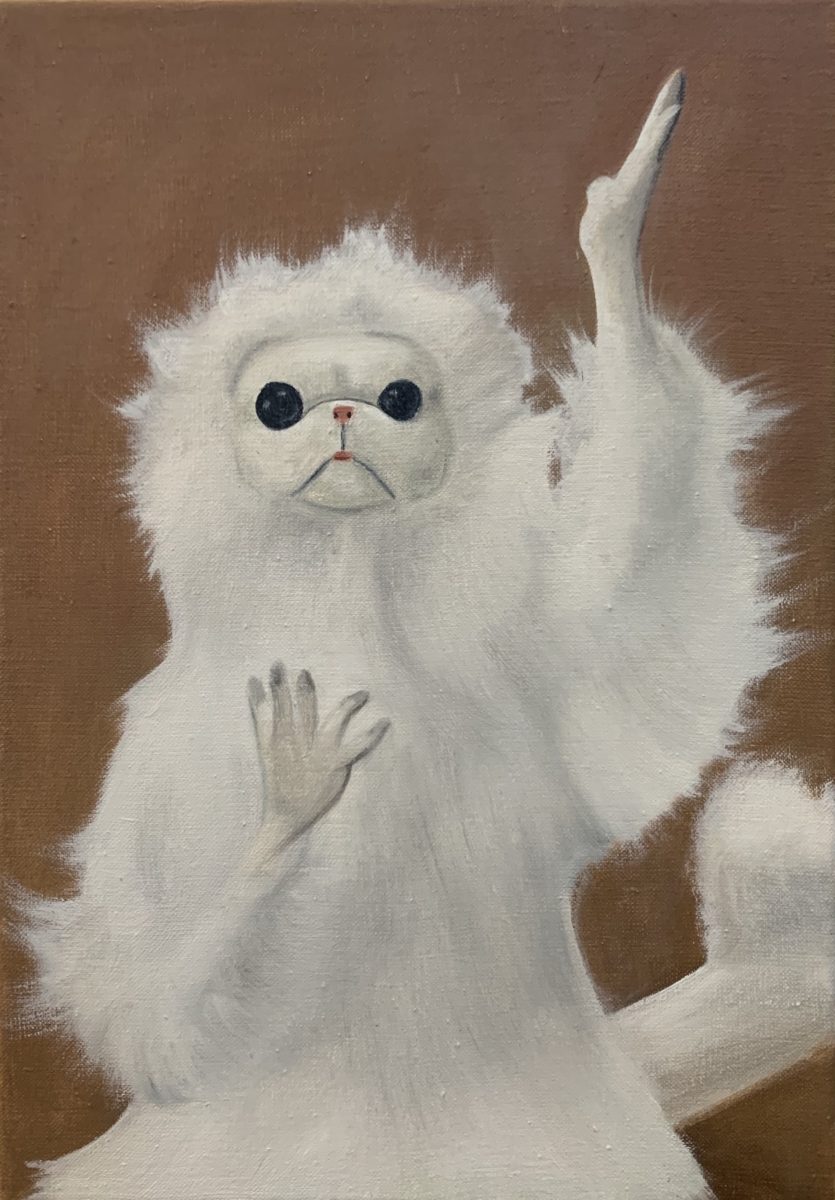

Hero, 2019

When I first encountered the work of Lydia Blakeley in London this autumn, my immediate impulse was to take out my phone and photograph each painting. Her images of prize dogs are set against a green screen background, while their owners’ hands and lower legs occasionally enter the frame. The unusual, close cropping of these paintings suggested to me something of the rapid circulation and visual saturation of the digital realm. Images are shared and re-shared via social media, while press agencies race to upload high-resolution photographs almost instantaneously; stock images can quickly become memes, and a simple screenshot easily distorts an image, divorcing them from their original context.

“The source imagery for the inspiration behind the paintings seems to almost always originate from the digital life I spend online,” Blakeley agrees, “whether it’s on social media, scrolling through Instagram or newsfeeds—that’s always a starting point. I literally just have saved images; I save images to my camera roll. I’m constantly screenshotting. I might have an image in my camera roll for, like, a year, and then I’ll suddenly start working on it.” The subjects of her paintings range from a firefighter rescuing a cat in Russia, dogs parading at Crufts and groups of women getting absolutely wrecked on booze at the horse races. Blakeley’s source material comes from all over the globe, as much a reflection of our contemporary moment as it is a practical means of painting in the modern world.

Consider this: how many pictures do you have saved to your camera roll? I currently have 6,796—a mixture of screenshots; snaps of items I plan to sell on eBay; my sister’s cats; poorly lit selfies and other visual ephemera. The camera roll is perhaps the most immediate reflection of our everyday lives, offering an insight not only into our dullest and most embarrassing habits, but an indication of our interests and tastes, right down to the memes we save and share. We all need a laugh every now and then, after all, but I am sure that I would rather die than have someone wander freely through the full collection of images—this intimate terrain of me—looking at whatever they please and passing judgement.

Blakeley’s choice of subject matter is undoubtedly infused with humour, brazenly placing the minutiae of our daily visual culture at the very heart of her work. There is something fantastically absurd about painting a meme or one-shot news story, transferring what is inherently a lightning-fast cycle to the slowest medium of all. Blakeley will often paint multiple works as part of a thematic series, at times even going so far as to paint multiple versions of the same subject, only viewed from slightly different angles. She will work with the images available online, in a process that is reflective of the digital experience of visual over-saturation, familiar to so many.

In Blakeley’s MFA degree show at Goldsmiths this summer, she exhibited a series of eight paintings of the Persian Cat Room Guardian meme, featuring a stuffed toy cat seated on top of a box, with arms outstretched and a bizarre expression of incredulity. “I decided to paint this character because it’s so funny and represents so many thoughts and feelings, but I just don’t think it would have had the same impact if I hadn’t done it from all the different vantage points that were available online,” she says, when we speak over the phone one cold afternoon in December. “It’s so strange to dedicate your time to keep focusing on this one thing, and I guess it seems like a weird thing to do, but it’s really just like when people collect things. It’s a collection.”

“The source imagery for the inspiration behind the paintings seems to almost always originate from the digital life I spend online”

Blakeley may have only graduated from Goldsmiths this summer, but her newfound success as an artist has been a long time coming. Just a few years ago, she was working in fashion retail in Leeds—a job she had held since school. She worked hard, progressing from the shop floor to assistant manager over the years. With a longstanding interest in fashion, Blakeley embraced the world of retail, ripping out images from magazines like Vogue, InStyle and Elle. She would attend life drawing classes in her own time, and completed a correspondence course in painting and drawing. “I still have files and files full of adverts and editorial; visual things that were amazing. That inspired me,” she recalls. “I’d collage them together, or I did start doing the odd painting, but it was a real hobbyist approach.”

Then the financial crash of 2008 hit, and her job was increasingly squeezed. Sales and productivity targets were raised, and she and her team found themselves at breaking point. Blakeley began to consider the possibility of university, something that she had never given much thought to. “My family were a bit perplexed, wondering why I was doing this when I already had a career.” Over the years, she had unwittingly built up a portfolio, a body of work that consisted of rough sketches, collages and occasional paintings. She took a chance, and applied to Leeds College of Art in 2012. When she found out that she had got a place on the BA course, she was thirty-two years old. “They saw something in me and I will always appreciate that,” she says, firmly.

Her original affinity with collage has remained, a hangover of those early scrapbook impulses. “I’ve always been really interested in collage in painting; how you can build up these scenarios and images, and the viewer won’t necessarily know that it’s an amalgamation of three or four images. It’s an enjoyable way of doing things,” she explains. “There are so many ways you can reflect the world, and what’s going on in the painting process itself. Obviously it’s a slow medium—it takes time, it’s built from layers—and so I like the idea of creating that space where viewers can reflect on that.” In paintings like The Three Graces, various groups of women have been combined to produce something closer to an imaginary archetype; a perfectly imperfect cliché, so familiar as to be a mirror of our own reality.

Animals are a recurring feature of Blakeley’s paintings, from pet poodles to glossy hounds and jumping horses. Far from a deliberate thematic tactic, it was in fact through exhaustion, self-doubt and pure coincidence that they first came about. In the first year of her MFA, an intense crit sent her reeling, leaving her unable to face being in the studio. She needed to get out; to get out of her own head. Where to go? Blakeley headed straight to the National Gallery. “I was walking around taking pictures of the paintings. I was looking and looking. I don’t know if it was art fatigue, but it got to the point where I was just taking pictures of all the animals in the corners of the paintings,” she recalls. “I was uploading them to Instagram Stories, and people were responding. They’re not the focus of these paintings, and there’s something really humorous about them too. They’re so cute and wonderful, and heartwarming.”

Blakeley returned to the studio with these images on her camera roll. Not long after, a strike at Goldsmiths led to teaching being suspended. Left to her own devices, Blakeley experienced an “existential crisis”, and began to gather more images of animals, this time from Crufts, billed as “the world’s greatest dog show”. “These perfect, pedigree, almost alien dogs, shot on green screens, are so characterful. The spectacle of these shows is very cinematic.” She points out, too, the parallels between a prize pet and the commodification of our lives on Instagram: “Pet breeding and pedigrees… it’s just another handbag, a form of consumerism or branding; they become these objects.” She began to make tiny paintings from these images, with the humans cropped out. When the art college resumed, her teachers told her to stop making these new works—advice that Blakeley has resolutely ignored.

“These perfect, pedigree, almost alien dogs, shot on green screens, are so characterful. The spectacle of these shows is very cinematic”

Dog shows continue to fascinate her, and it is a theme that she has upheld in her recent work, including the first of her series that I encountered. “At Sunday Art Fair, I was able to get the dogs back in there. I had done a very large-scale painting of a dog with a rosette. There are dog shows in America, but there is something very British about them. This is a nation of dog-lovers. It’s so steeped in this art historical context, from Gainsborough to Stubbs; maybe it’s seen as niche and unfashionable, but I quite like unfashionable things,” she reflects. “There’s an accessibility; it’s not trying to be anything else. It can be a beautiful thing, especially for people who aren’t in the art world, who might otherwise feel a little bit intimidated.”

- Left: The Fall of the Damned, 2019. Right: The Massacre of the Innocents, 2019

That accessibility is an important part of the appeal of Blakeley’s work; she invites her viewers in with images that many will recognise from some strange corner of the internet, like a half-remembered dream. She sets us at ease with humour and light relief, but there is inevitably a political question at play when it comes to imagery that could be described as kitsch. Who, exactly, is in on the joke? “I definitely love humour, and I love to be able to bring that in. I don’t know if I explicitly wanted to do it; it just happened. Even if I try and be quite serious, there’s always a humorous element, although sometimes it’s quite subtle. But underneath that humour there’s a darkness, maybe a sadness too. It’s always masking something, in some respect.”

“I do certainly think that, with the Britishness—especially from my background—all the subjects, especially the races or dog shows, there’s an oddness to it all, which in itself is quite funny. It’s just, why would you do that? I’m not really sure.” Blakeley was born in Bracknell, Berkshire, a new town developed to ease the pressure on bombed-out London post-World War II. Growing up there, she developed a love of kitsch, something that she continues to embrace. “It’s something that has surreptitiously embedded itself in me. It’s one of those things when you’re grown up and you go to your gran’s house, it’s all those things around you that you absolutely love, little figurines and patterned wallpaper, things that are a little bit unfashionable but really lovely as well. It’s all cyclical, and things go in and out of fashion.”

“Underneath that humour there’s a darkness, maybe a sadness too. It’s always masking something”

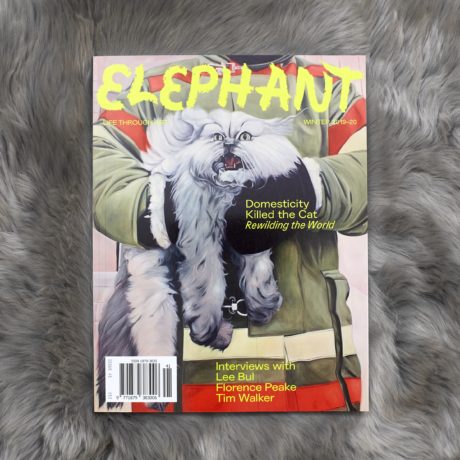

Unfashionable her subjects may be, but Blakeley is firmly on the rise. Already, she has a solo show in Los Angeles, at Steve Turner Contemporary, planned for January 2020; a group exhibition in London, with FBA Futures, is slated for the same month. Her work is currently on the cover of Elephant’s very own winter issue, and she is working around the clock to fulfil demands for shows further ahead next year. Not that she’s let it go to her head; she has moved back to Leeds, and visits London and the United States only when work demands it. She jokes that, in a way, she has come full-circle: “The art world, oh my god, there are so many parallels to retail! The retail world that I was trying to escape… well, I’ve actually entered into hyper retail with the art market. It’s not a bad thing necessarily, but it draws so many parallels with the commercial gallery and the art fair.”

Blakeley keeps herself grounded by immersing herself in painting, something that she continues to adore, even as it becomes a core part of her career. “I feel like, once I’m in the studio painting, it’s a way of switching off. Everything does melt away, and you can just focus. Not to say that it isn’t stressful, and you’re constantly problem solving, but it’s a very solitary headspace that I feel is good for me. It’s the best kind of work that there could be. It’s always a learning curve. I absolutely love painting; it is a joy. I love that struggle, and I love that I can reflect on that and learn from it.” On that note, she must get back to work, I say, and our conversation draws to a close. We end with a quote from Dorothea Tanning, whose exhibition at Tate Modern Blakeley visited three times this year. She repeats it carefully to me, like a mantra, “People ask me why I paint, and I tell them, it’s a drive.”

Elephant Issue 41 is out now

BUY ISSUE 41