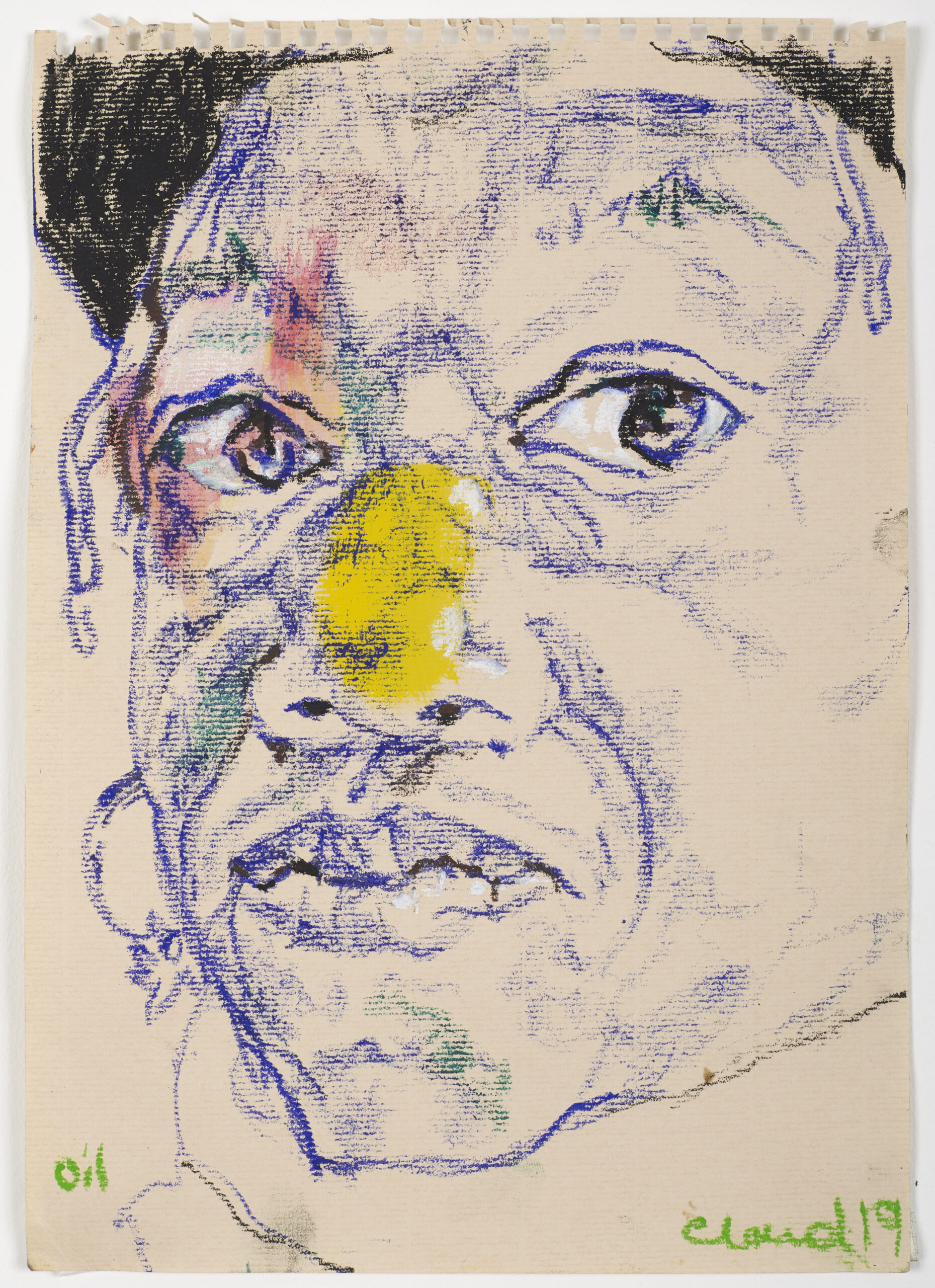

Claudette Johnson is an artist who knows the power of a single mark. In Oil Sketch (2019), blue pastel lines traverse the textured surface of the paper, lightly gathering in some areas and densely amassing in others to reveal a face. Staring out from the frame, Johnson’s portrait is, however, about more than simply capturing her own expression. It is about the transition of one line into another. It is about the galvanising process of a series of subtle moves and manoeuvres from the hand to the stylus to the page in the broader formation of a whole form. It is about the progression and digression of the drawn line, its twists and turns and returns to former marks and shapes in the development of a once imagined now realised image. And it is as much about the incoherence – the blankness and blocking of space, the illogical smudge or stroke in the seeming logic of it all – as it is about a form’s overall coherent ‘finish’.

As Johnson herself states, Oil Sketch not only captures but enacts ‘numerous re-sightings of the same form’. Working over and into preceding marks, re-envisioning old visions, Oil Sketch becomes a palimpsest of former decisions, a map of the ongoing discovery that is Johnson’s own creativity, and an exercise in the trying and making and doing of art. With smudges of yellow and rose, and accents of green, black and white beneath the roving blue lines, Oil Sketch is as much a portrait of art-making in action as it is of the artist. Johnson’s drawing – a sketch evidently taken out of a ring-bound book, perhaps never to be seen until now – becomes then a metaphor for all the works displayed in the Drawing Room’s impressive latest show, The Time of Our Lives. In its exploration and exposition of the process of drawing, Oil Sketch points to the women artists who have also innovated the form and whose own evolving and politically engaged practice has led to a new generation of artists to harness the language of the line. In framing her “humble” ‘sketch’, Johnson alerts us to a transition that this exhibition celebrates: the reframing of drawing itself, by artists like Johnson, Sonia Boyce, Sutapa Biswas, Margaret Harrison, Monica Ross, Soheila Sokhanvari, Lizzy Rose, Jade de Montserrat and Kate Davis, from a preliminary and “feminine” mode, into a main, feminist praxis worthy of the frame and gallery in which it is displayed. Johnson’s Oil Sketch moves us from the experience and experimental freedom of drawing as draft to drawing as deserving discipline, portraying more than a face, but a whole progressional shift in the politics and power of this art form and in the artistic – drawn – output of women in general.

Johnson’s Untitled Portrait (1990) brings to the fore this emerging political consciousness in and through the art of drawing. Oil Sketch may move in its immediacy and its sensitive placement of line and colour, but Untitled Portrait impresses with its sheer scale, its undulating movement of pastel and growing gradation of browns, beiges and whites, to present an arresting vision of a woman. Who, exactly, the woman is, we cannot be sure, as Johnson states that her own features have been transposed over those of the original sitter, but what is certain is the irrepressible assertion of the female figure. This is exactly where the political power of Johnson’s work sits: not in the intermix of the unknown with the familiar that the crossover of personal markers with those of a stranger holds, but in the imbuing of this new drawn persona with a palpable and striking presence that says ‘you can’t deny me’. Aside from the erotics of viewing and being viewed – for Untitled Portrait is not a game of seduction or social posturing – Johnson’s drawing is a work of recognition: firstly, of the artist recognising her own power in the initial image and image-making of another; and secondly, of a new emerging Black woman recognising herself in the space of the paper, the frame, the unfolding contours of the visual field and out into our own. This emphasis on taking up space and proudly recognising yourself within it is extended not only through the size of the work but also through Johnson’s decision to draw – rather than paint or sculpt – this declarative statement of power and pride. Still viewed at the time as a form of draughtsmanship, drawing here is doubly subversive in its ability to insist, along with the persona it portrays, its gallery-worthy primacy. Both drawing and the drawn in Untitled Portrait assert their in-erasable power, their right to be respected and represented in institutions, at a time when the art world was ignoring if not completely ‘erasing’, the artistic presence of Black women.

This acknowledgement and incorporation of erasure in Johnson’s drawings chimes with that of her contemporary, Sonia Boyce. Akin to Johnson in her reclamation of drawing as a radical and empowering practise, Boyce adopted the medium at a time when painting was still being hailed as the ‘pinnacle’ of (male) artistic endeavour. Boyce has outlined in an interview with Courtney J. Martin the conflict that broke out amongst students at St Martins School of Art over the representation of women and the mediums lauded or derided at the time. Boyce’s decision to choose drawing, as well as the naturalistic representation of women in domestic settings, was doubly subversive and loaded, a countercultural act and quietly political claim for what was being derogatively deemed ‘feminine’ and retrogressive by some of her peers. Bolstered by her engagement with artists like Frida Kahlo, Kate Walker, Margaret Harrison and Monica Ross (the latter two of whom are included in this exhibition) and her own involvement in the British Black Arts Movement, drawing became the first feminist tool through which Boyce asserted her own powerful presence in the British art scene. Situated between the feminine and feminist, Boyce’s drawings, which explore her own upbringing and life as a young Black woman and artist in 1980s Britain, formally centre what was side-lined and thematically insert what had been erased.

In Mr close-friend-of-the-family pays a visit whilst everyone else is out (1985), process and praxis, inclusion and erasure violently meet. Looking directly out at the viewer, a young Boyce stands to the right of the aforementioned ‘Mr close-friend’ whose hand sinisterly reaches towards her chest. Behind them, an intricate, deco-like pattern proliferates and tessellates upwards, disconcertingly amplifying the growing sense of claustrophobia, entrapment and soon-to-be-realised violence. The pattern in question – wallpaper from the family house – warps the weft of safety and comfort woven into the notion of home. As if the drawing were a window unto a small room or an auditorium around the main stage, Boyce has a frame of hands conspiratorially circling the scene and unravelling the title of the work. And if this were not enough in articulating the distress and duress the child is under, the whole drawing is delivered in charcoal, the stark and smudging technical use of which holds an obvious parallel in the haptic horror and psychological staining about to take place. Vulnerability and adult culpability, innocence and guilt unsettlingly converge in the motif of drawn and far-reaching hands. Touch is everywhere implied, issuing from the abuser’s hand – the too ‘close’ false ‘friend’ – and the victim’s resistance, to the older artist’s creative manual expression through the medium of drawing. Thus, in the narration and exploration of her own sexual abuse, the careful handling of being painfully manhandled comes full circle, and a young Boyce hits back through the creative expression of her slightly more mature artist counterpart.

What strikes me about Boyce’s drawing – a work that caused shockwaves amongst her community at the time – is the expectation for us to handle this work with care too. You cannot walk past this drawing; you cannot cursorily cast your eye across its superficially skin-deep surface or hard delineations of encroaching bodies and enclosing walls. Rather, you must stand and hold the trouble this work presents to us. As it holds you, you must hold its pain and irrefutable power in return. The harrowing hands that invoke the implied violation reach out and evoke our own sympathy, even complicity, in the abuse women are subject to behind closed doors. But it is the smear and stain of the material, the deliberate imprint and child-like play of the charcoal – the first stylus given to children and artists alike – that has the most resonance when it comes to the process of drawing, the issues it can express, the ideas it can encircle and extrapolate at the simple deft movement of a hand.

Though but one in a series of drawings that form an overall narrative, Boyce’s work narrates what cannot be fully expressed. In this, Mr close-friend-of-the-family pays a visit whilst everyone else is out not only pre-empts a later stage of Boyce’s practise – chiefly collage, video and typographic-based work – but demonstrates the proximity between writing and drawing, word and image. In fact, her decades-long Devotional Collection is one of the natural successors to her earlier drawings (the revolution and evolution prompted by the form is continuous!). Drawn works for the series, some of which were developed for her Golden Lion-winning British pavilion, Feeling Her Way (2022), at the Venice Biennale, emphasise the graphic import of words, not only by decorating the names of Black female vocalists and musicians but enunciating them on the page as if the script was able to elicit the auditory qualities of the person cited. In this, Boyce again reiterates, through dexterity, joy and play, that drawing is a language, one fully open to the rhetoric, performativity and action that speech as well as writing brings about.

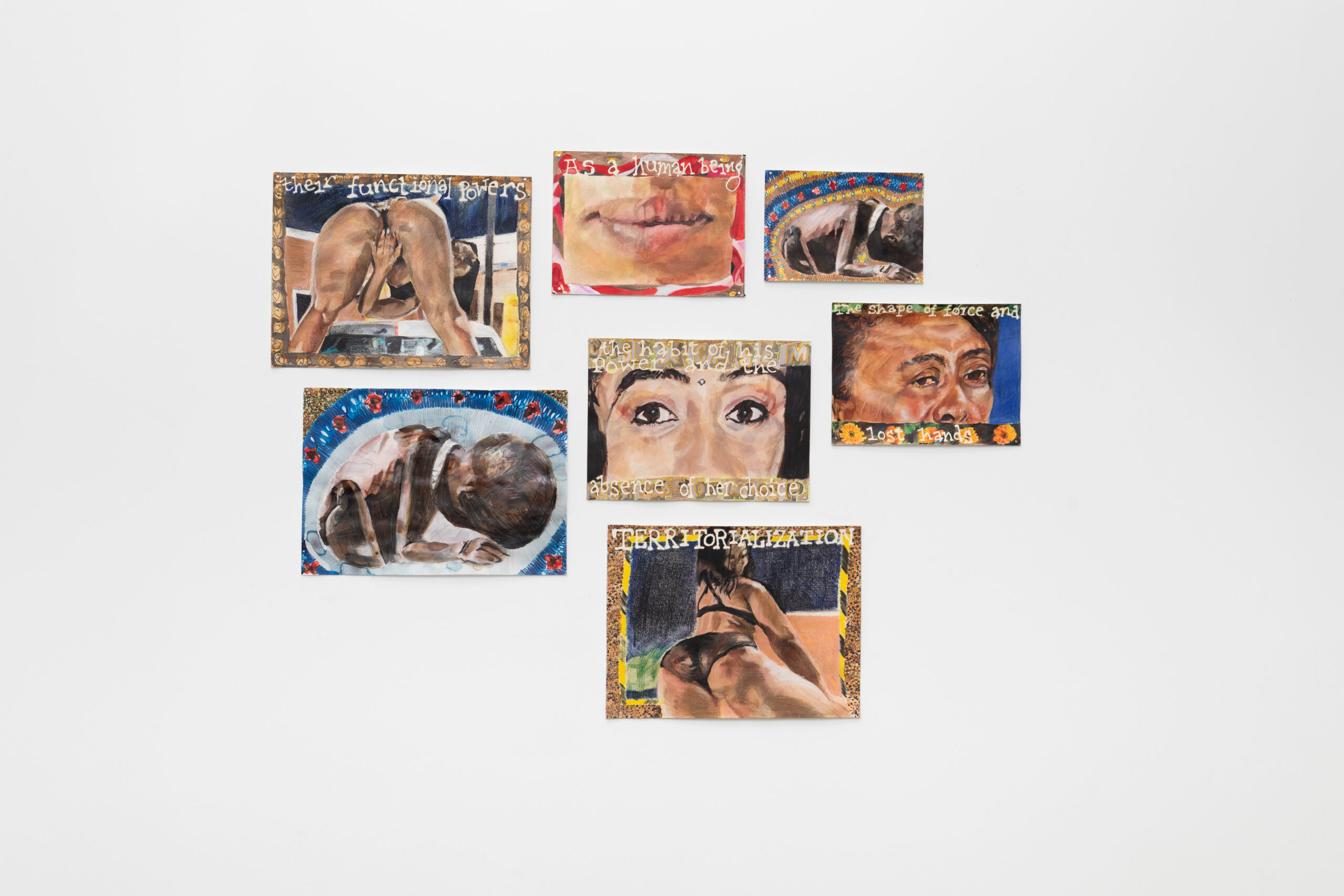

Two other artists whose mixed media works see the vocabularies of writing and drawing converge are Margaret Harrison and Jade de Montserrat. Whilst Harrison’s work devolves a deluge of script and interposing images across the back wall of the gallery, Montserrat’s unfurls from the skies, looming over us in joyous multi-coloured and generously large lettered banners. Both demonstrate that the language of drawing commands as well as creates space, pushing into the realm of air, towering over us and around us, creating constellations of meaning designed to disrupt the preconception that this is a flat, compressed and two-dimensionally constrained form. Collagic in nature and cacophonous in its effect, Harrison’s Beautiful Ugly Violence (2003-4) literalises the interconnections between the cultural and socio-political conditions of a place and the sexual and physical violence that women therein encounter. Collating research into a poster-style display, Harrison synthesises and strips bare the prejudices and stereotypes – the everyday sexism – underpinning the collective violence women endure, writing/drawing into these raw realities a whole arena of feminist voices, facts and feelings. Montserrat’s work, however, turns her mixed media works – and thereby drawing – into a focalised site to examine trauma as well as humanise the traumatised. Using pencil, watercolour and gouache, Montserrat highlights the fatal violence Black and brown women – Sarah Lynne Reed and Savita Halappanavar – suffer at the hands of the state. Yet her works are not graphic recapitulations and visualisations of such systematic brutality and neglect; rather, through pointed and poetic statements and fragments of faces, Montserrat redirects our attention to the humanity, vulnerability and beauty of these women, and renders drawing a site in which to remember and commemorate their stories, as well as a place to reawaken our social consciousness and reorient our sense of justice. Unlike her larger drawings draped from the ceiling of the gallery, which borrow words from bell hooks and Sojourner Truth, Montserrat’s smaller, quieter pieces converse one with the other, as well as stirring conversation amongst viewers. Whether through banner-like works echoing the kind of statements evinced at political marches, miniature memoria and Black mnemonics, or collagen distillations of the ‘ugly’ truth of patriarchy, Monserrat and Harrison use drawing to enquire, protest and disrupt both socio-political and artistic conventions.

Shaking up the conventional and commemorating the unremembered is also a characteristic of Soheila Sokhanvari’s drawings. As with Boyce, Sokhanvari returns us to the politics of the medium by employing Iranian crude oil to draw. Converting the symbolism of crude oil from corporate resource to a source of creative potential, Sokhanvari employs a cultural and geographical marker to personal effect. After coming to study in the UK as a teenager, the artist became exiled from her homeland, Iran. Her delicate oil-strewn drawings are, then, evocative both of lost land, lost experiences and lost memories post-revolution; they are darker tributaries to past love, lighter rivulets to present grief. In works like True Love and Paradise Lost (2023), this poetics of loss takes on the property and process of memory itself, so that figures and faces (in part derived from photographs) are hazily rendered in blurry, pointillistic snapshots. Sokhanvari’s drawings, therefore, appropriate the erosions and erasures, the rewritings and reworkings associated with acts of remembrance. It is as if these works have come into being through tear-filled eyes, filtered through an emotional lens of longing which distorts as much as it testifies to the true rememberings of the heart and mind. Although drawing reinserts Sokhanvari into places and spaces, positions and situations to which she had no physical access, the medium of oil, with its nostalgic sepia tint and unsettled saturation over the paper, carries her – and us – back into that era, back into the arms of loved ones (as with True Love) and a beloved homeland. Oil then becomes a material that sticks: as a slick spring of affectivity, a resounding residue of past histories, and as a politically sticky reserve that separates and unites, generates wealth and denigrates the most marginalised people indigenous to areas in which it is found. Rather than spilling oil, Sokhanvari spreads its rich and problematic connotations, both individual and general, across her exquisitely moving works, allowing its political resonances to quietly accrue.

Joining Johnson in her accumulation of prior marks and mistakes, omissions and admissions, Sokhanvari embraces the liberating process as much as the liberal politics of drawing. Much like her miniature egg tempura paintings on vellum featured in her incredible show of 2023, Rebel Rebel, these oil refined works dare to redefine and push what drawing, what culture, and what women can do. Inserting herself – and the feminine presence – back into the visual frame, Sokhanvari’s artwork, like all of the brilliant drawings in this timely, peerless exhibition, asserts the concerns and creativity of women, and reclaims the form as a feminist mode in which to reinvent and redirect the line to their own liking. Alive to the issues of today, as much as those experienced in the 80s, The Time of Our Lives powerfully conveys that drawing is as much about constructing a new present as it is about envisaging the past, and that by following the line and making their mark, women artists who draw are already shaping the future of tomorrow.

Written by Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

The Time of Our Lives is on at the Drawing Room until 21st April 2024.

FIND OUT MORE