Community and crisis are themes that have long preoccupied María Berrío, but when we first spoke earlier this year neither of us could have predicted how prescient these subjects would soon seem. At that point, the global pandemic was only just beginning to tighten its grip, international Black Lives Matter protests had yet to reach their apex, and society had not yet grappled with concepts of “unprecedented times” or a “new normal”.

There is something prophetic about Berrío’s delicate pre-Covid “paintings”, which are in fact made from carefully collaged Japanese paper. The sheets are filled with natural imperfections and an inherent softness that the Colombian-born artist likens to watercolour. Her scenes invariably speak to female strength, aspirational matriarchies and an embedded sense of reciprocal society, all the while calling on the South American folklore that surrounded her as she was growing up.

María Berrío, Oda a la Esperanza (Ode to Hope), 2019. © María Berrío. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

“I try to portray the idea that my characters are part of a full world, who can’t exist without others,” she explained, during our first conversation. “I think a lot about community, particularly about certain political situations happening at the moment. In Wildflowers, for example, there’s a group of people all standing together, and the title comes from the idea that flowers thrive where they are not supposed to. It relates to the immigration crisis, but here I picture a community coming together and standing strong. When you look at the painting I want you to feel some kind of hope.”

There is no denying that our current situation has shown both the ugly and beautiful sides of humanity, and so I can’t help but wonder whether Berrío has managed to maintain an optimistic outlook in recent months. When we speak again, she explains that making work seemed like a futile endeavour for a short while: “I had to ask the question, ‘Should I be an artist? Should I be making work when there is so much else going on?’ But then I came to terms with the fact that this is the way I come to understand the world, and to protest. Art and music foster hope.”

Pre-lockdown, Berrío’s focus had been on a new body of work for her solo exhibition at Victoria Miro, originally scheduled for June 2020 but now postponed. In what again feels like an oracular statement, she explained then that, “I’m creating an imaginary village through a series of paintings, which explore ecological and political disasters, all the problems of our reality. They include interiors and exteriors, which portray how humans continue to survive in these situations. There’s plenty of magical realism and the works are very big, so I hope people can relate physically to the environment and experience something different, before returning to the madness of the real world.”

“I had to ask the question, ‘Should I be an artist? Should I be making work when there is so much else going on?’”

Fast forward a few months, and isolation, limited access to her studio and a new sense of introspection took hold. “The imaginary village and my own reality have come together,” she says, before adding, “I began working from home, making these little paintings that I could eventually carry to and from the studio. The small pieces reflect our current times, and they feature both my own image and that of my son, which is a new subject matter for me.”

While Berrío has become known for her richly decorated surfaces, which pay mind to intricately crafted costumes, elaborate flora and fauna, and occasional mythical beasts, these new pieces seem to hold an entirely new sensibility. Usually, her paintings feel expansive, not only in their literal size but in the scenes that they depict. Deep oceans and vast mountain ranges give way to capacious skies, and even interior settings feature vignettes into the world beyond, by way of windows and doors.

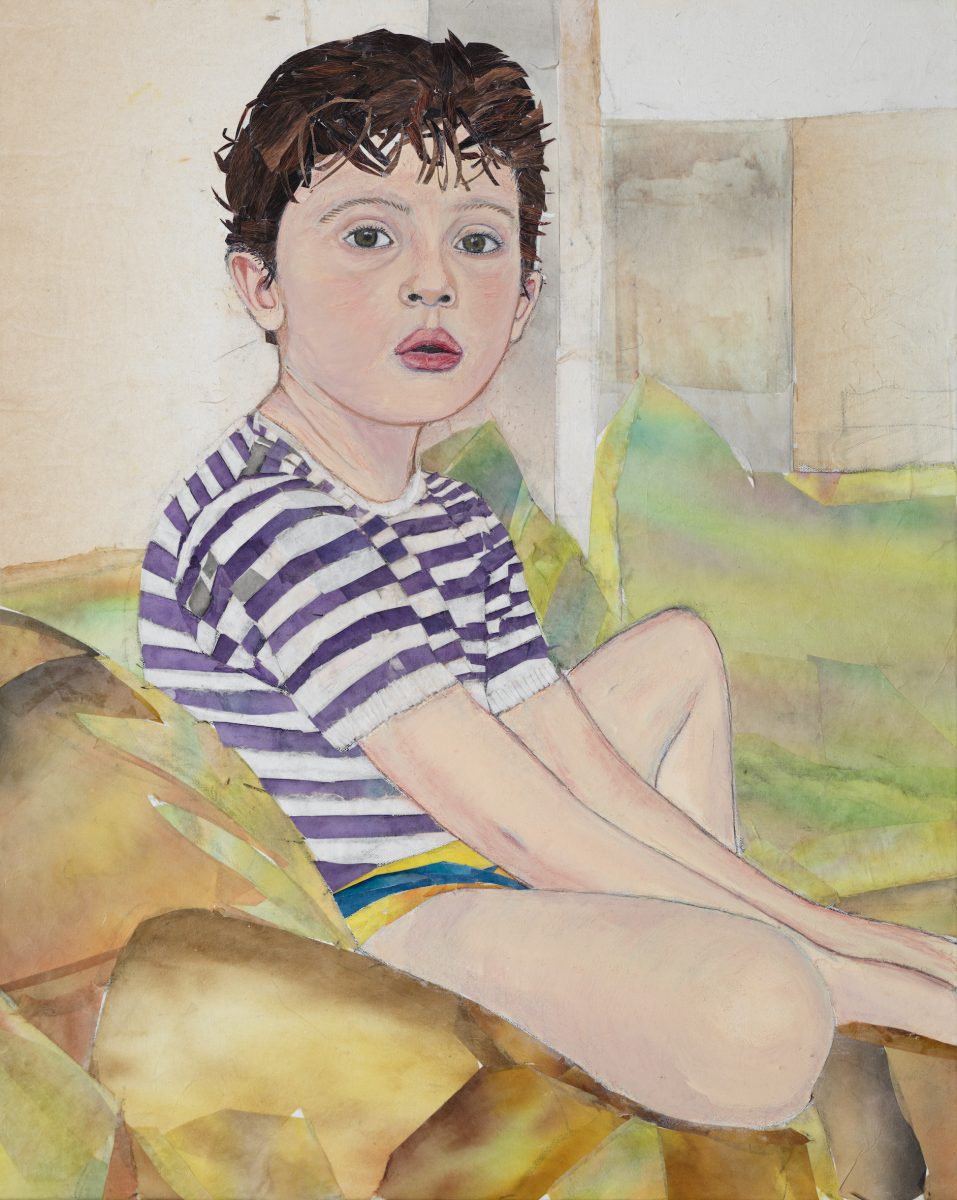

- Left: María Berrío, Baz, 2020. © María Berrío. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

- Right: María Berrío, Interior of a Moment, 2020. © María Berrío. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Conversely, recent pieces such as Baz and Interior of a Moment reflect a quotidian domesticity. In the former, the artist’s young son appears on the couch, looking mildly quizzical, amid muted walls of beige and brown. Meanwhile, the expression in the artist’s self-portrait speaks to the strange, anxiety-ridden boredom many of us have experienced in recent times.

“I think a lot about community, particularly about certain political situations happening at the moment”

“The original works were about creating an imagined space that had suffered catastrophe, longing and grieving,” she says. “Then I found myself in that room.” It is a notion that many of us can empathise with, particularly as we navigate the constantly evolving consequences of our present existence. Berrío has been based in New York for some time, where a spirit of what she terms “coping and change” has prevailed against a backdrop of “protest, helicopters, fireworks and ambulances”.

It is an environment that is seemingly at odds with a practice that is defined by painstakingly pulling apart and reassembling delicate, handmade paper. Berrío works with a fabricator in Japan, where communication includes well-meaning gestures (they don’t share a common language) and the craft remains a family business. “By using this material, I feel the love of the families who have been making it for so many years,” she says. “When I receive my paper, I treat it as a gift. It is something very valuable. I’m very careful with it, even though I rip it apart!”

The act of breaking something apart in order to rebuild it is an apt metaphor for 2020 and beyond. The status quo irrevocably shattered, forcing us to reflect on political systems, social injustices and even personal habits. Berrío admits that the fear and grief can sometimes feel overwhelming, but there is definitely a sense that hope will prevail, particularly in New York, where incredible acts of kindness and courage have played out against catastrophic death tolls and acts of brutality. “Ultimately we have a responsibility to the next generation,” the artist assures me. “My son is only six years old, but we’ve had to have serious conversations about racism and the effects of the pandemic. Children are needing to learn these things fast.”

The empathy and compassion that Berrío hopes to see in the world around her is always present in her work, whether it be the symbiotic nature of woman and beast, the simple act of communal gathering, or a celebration of difference. In Syzygy, for example, a woman nurses a feathered wing in place of an arm. For fans of the Brothers Grimm, the similarity with The Six Swans (a tale in which a princess must lift a curse that has turned her six brothers into birds, by sewing them shirts made of aster flowers) might be apparent. It is a story of labour, endurance and loving suffering that Berrío is not familiar with, but she immediately identifies with the sentiment. “In a sense the woman with the wing is a symbol of the outsider who struggles because she is different, but that is what makes her special. It is the wing that sets her apart and will ultimately set her free.”