The act of birth has become highly industrialized for some animals—something that is seen most obviously in the dairy industry. What first drew you to the location of the dairy farm, which was eventually shown in your 2014 work The Udder?

I was drawn to an organ, the udder, which led me to the farm. I was looking for small, family-fun robotic dairy farms. Most are either DIY or full techno. I was after something in the middle, hand methods that were starting to be replaced by robots, where the cows can milk themselves twenty-four hours a day if they choose to.

There is a particular focus on the udder—the shape and form as well as the practical use of it. It reminded me of our complicated relationship with human nipples, where the main function, that of sustaining life, becomes really twisted, and the image of the nipple looks quite surreal when displayed so close up. Did you feel any parallels here while you were making it?

Parallels with nipples? Sure. I filmed a new mum’s nipples really close up just before making The Udder. It’s pretty violent when you go so macro—witness revulsion and desire doing their dance. Then, I think, the teats wander into psychic allusions of the phallus. And in the film, when the teat gets cut open, and the young girl cuts off her nose, you have a layering of all these strange body parts—nose, teat, penis—being split open.

There is an idea of innocence surrounding birth and youth, which obviously has religious connotations from many years ago, and which seems at threat to modern technology in your work, as something nurturing and natural becomes tainted and abused. Do you see the work as taking a moralistic stance?

I don’t like to think my work suggests technology as the culprit against nature. That would pretend it’s outside or above. I do try to articulate a violence entrenched within our relationships towards each other and the world, which we are told is just normal, or that we’re mad for thinking any different. And I love fables, and how they zoom in and wildly exaggerate. They allow me to invent new worlds and characters and play out imaginary scenarios.

When I saw the film installed I was really struck by how sexual it felt when I first walked in. Can you explain a bit about how sexuality, chastity, contamination and innocence are all at play in your work?

Chastity became a central theme in The Udder, because of its power over other forces. In Milton’s Comus (1634), a lady is able to resist a debauched necromancer in the forest through the power of her mind. This was a close text to me when making the work, not because of its religious connotations, but because it describes a way out of an unbearable problem. I work with children a lot, especially pubescents, that age where you get lanky and your puppy fat starts to melt. I also think a lot about diseases and symptoms. Sometimes I invent them, other times I take what’s real. We know there’s disease in the air, and we’re all contaminated, and that doesn’t have to be a bad thing, but there’s still this attempt to separate and close borders, and be private and not let anything or anyone touch you.

Marianna Simnett, Blood in My Milk, 2018. Still 5-channel HD video installation. Courtesy of the artist and Jerwood/FVU Awards

Can you tell me a little about your latest work, Blood in My Milk, which is showing at the New Museum in New York?

Blood in My Milk is a five-channel continuous narrative comprising several of my films all bleeding into each other. It tells tales of violence and control, and consists of a motley cast of cockroaches, udders, children, surgeons, farmers, teenage boys and myself, often undergoing invasive procedures or at threat to disease. This is four years of my practice shown together in a space for the first time. It’s an overwhelmingly sensory universe inside my brain.

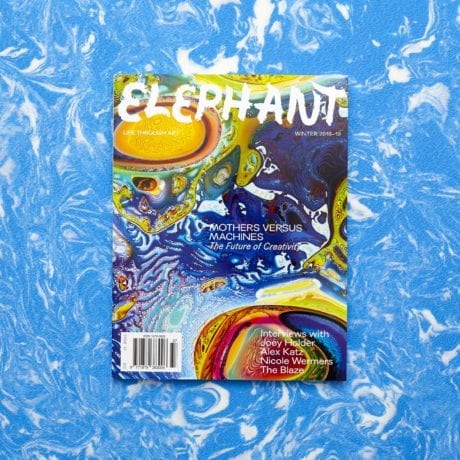

This feature originally appeared in issue 37

BUY ISSUE 37