Through my life I have learned to be patient—

to whisper—not to scream

to look beyond a square—

to flow with the sea—

to breathe the wind—

and to be proud to be an artist.

—Marisol

Marisol remains perhaps the most intriguing and least understood artist associated with Pop art. She was born María Sol Escobar in Paris in 1930 into a family that belonged to a peripatetic Venezuelan elite. Around 1935, they moved back home, and Marisol spent her early years travelling between the US and Caracas. She drew continually, recalling in the 1960s, “I always liked art before I thought it was art. I was always drawing, ever since I can remember.” She seems to have formally adopted the nickname her mother gave her, Marisol—which alludes to the Spanish words for “sea” and “sun”—in her early teens and used it professionally without a family name. In 1941, her mother killed herself and Marisol stopped speaking. She would later say: “I didn’t want to sound the way other people did. I really didn’t talk for years except for what was absolutely necessary in school and in the street … I was into my late 20s before I started talking again.” During this time, she attended grade school in Caracas and then high school in Los Angeles, where she took art classes at night.

In 1951, after a year in Paris, she moved to New York, where she continued studying, with Hans Hofmann, among others. Unlike so many of her artist peers, she was able, due to her family’s relative wealth, to dedicate herself to art from an early age, and she never pursued another career. She hung out with the Abstract Expressionist circle of painters at the Cedar Tavern but also joined up with a wilder beatnik group of friends in the 1950s. “I was a bohemian”, she would describe later. “I was high for about four years. I used to know a group in the Village who used to turn on with drugs. That was a very friendly time for me. We sort of lived together.” Her first sculpture mentioned in the press was in a 1954 New York gallery group show.

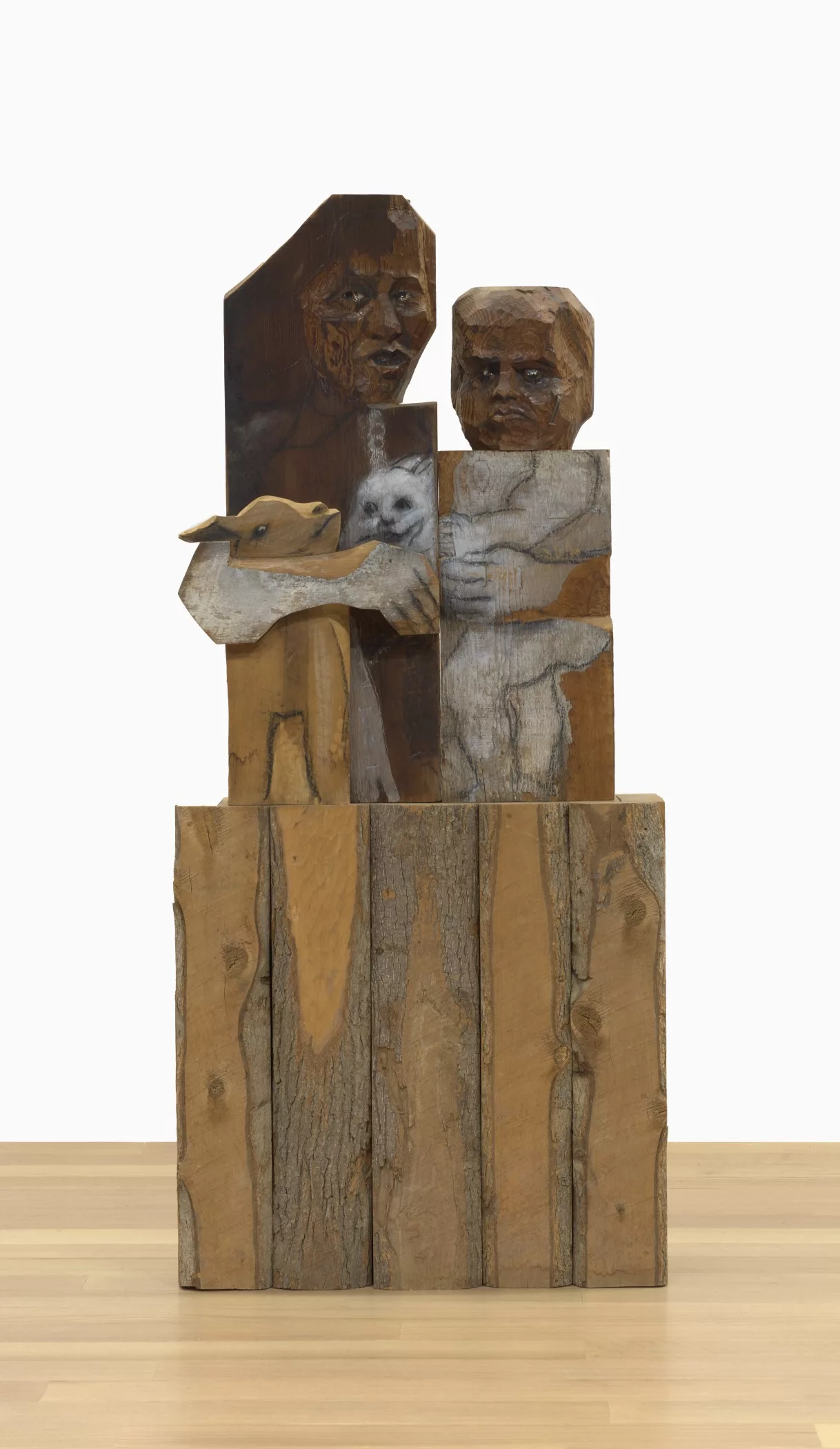

Her earliest, relatively small-scale works are from the second half of the 1950s, a period of dramatic experimentation for Marisol. They include trials with wood relief, plaster casting and stone. She most frequently made abstract terracottas and bronze sculptures populated by tumbling figures that she described as having been influenced by Auguste Rodin and his Gates of Hell. At the same time, she began work on a small group of reliefs and other objects that constitute her first sculptures in wood. Many late-1950s works depict troubled family groups, and the drawings in particular are rife with science-fiction references. These early works were included in a few group shows and drew the attention of Leo Castelli, who in 1957 included her in a show at his gallery with Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, followed by a solo exhibition later the same year. The parameters of Pop art were only just being mooted in the United States, and Marisol was featured in a number of articles that focused on her as part of a revival of craft or carving.

With little warning, Marisol left New York for Rome in the summer of 1958, arriving there in August. “I got so scared after I had my first show that I went to Europe and disappeared”, she would later say. “You start getting publicity, and then all of a sudden you lose everything you have.” But this was just the first of many protracted trips abroad that Marisol would take after feeling overwhelmed by the New York art world.

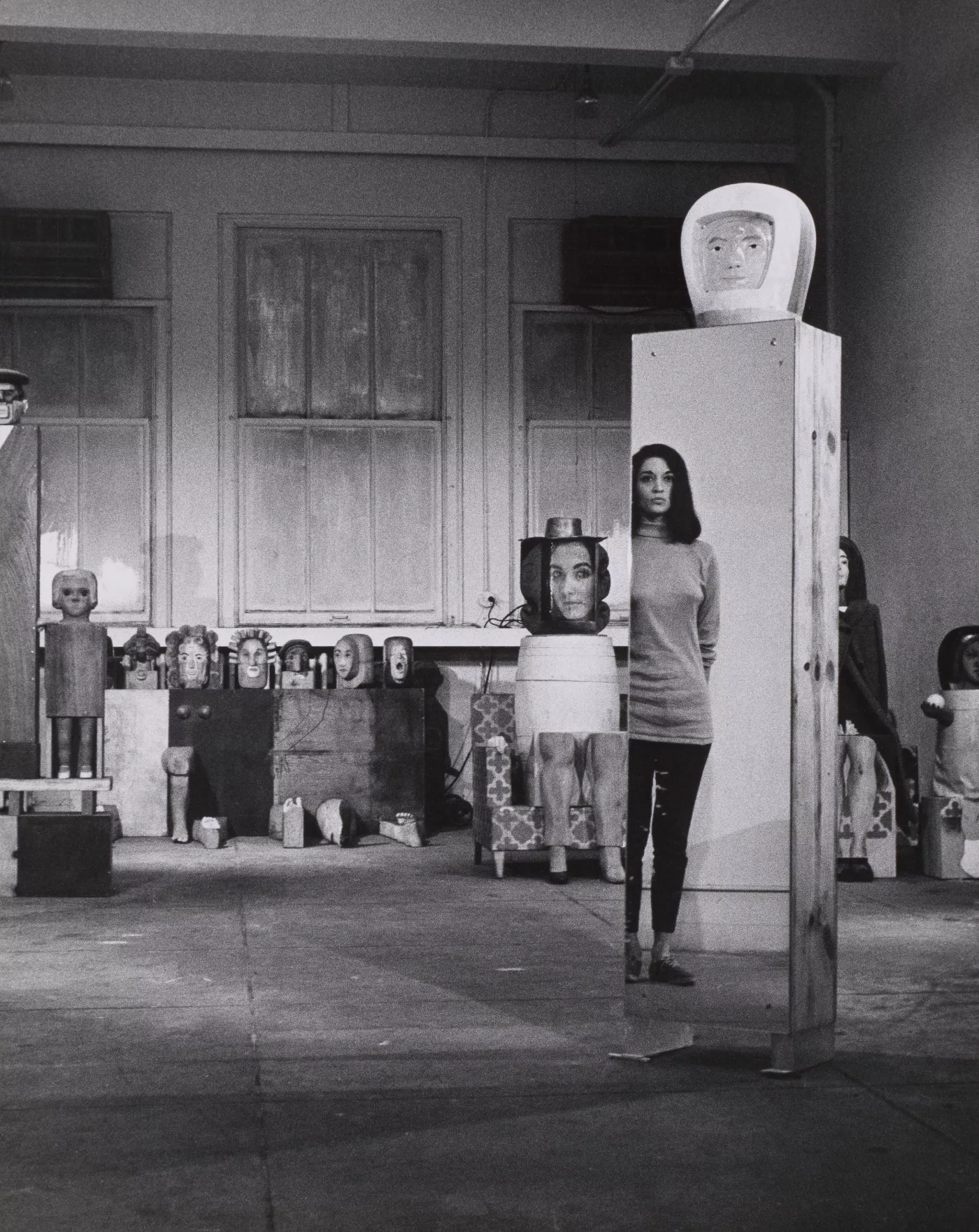

After more than a year in Italy, away from the New York art world, Marisol returned in 1960 with a new focus. That summer, she found a bag of old hat forms and began altering them by adding glass eyes and plaster casts of (almost exclusively) her own body parts. Soon, she made larger and then life-size assemblages, often including casts of her own face and hands, and began to incorporate drawings on wood along with carving. This combination of drawn and carved sculptural surfaces, body casts, wood and found objects from the streets of New York was wholly unique and easily recognisable in an emerging field of artists experimenting with silkscreen and Minimalist sculpture. These works constituted her breakout 1962 show at New York’s Stable Gallery.

At the dawn of the 1960s, after a decade celebrating the romanticism of Abstract Expressionist painters, critics were effusive in their praise for an artist who approached portraiture through a satirical lens and whose self-portraits, which could be both fragmentary and multiplied, transformed the genre. She quickly became a celebrity, with thousands lining up to see her exhibitions in 1962, 1964 and 1967. While she may be best known for her pop-culture subjects from this period—including depictions of icons like the Kennedy family, Andy Warhol and John Wayne—her most incisive sculptures of the 1960s tackled women’s roles in society, norms of gender and sexuality at midcentury, self-identity, Cold War politics and the immigrant experience.

For Irving Sandler, writing in the New York Post, Marisol’s “hilarious and caustic parodies” in her breakout 1962 solo gallery show in New York made for “one of the most remarkable shows to be seen this season”. That year, Life magazine featured her in its “Red-Hot Hundred” list, and images of Marisol’s work, reproduced in Time and elsewhere in the popular press, extended her reputation far beyond the art world. By the end of the 1960s, according to one critic, she had “been written about more than any living artist in women’s magazines as well as art journals”. In these works, her face, or body parts were everywhere. Speaking of these elements of self-portraiture in her works from this period, Marisol noted: “Sometimes I feel as though I’m being blown away. People say they pinch themselves to see if they are awake. This restores them to reality. When I do a portrait, but really do myself in the portrait, or use my own hands or shoes, it brings me back to reality.”

As a panel discussant on Assemblage art held around 1961 at the Artist’s Club, a key debating stage and gathering place for the New York School of Painters, Marisol was seated next to three male artists. She wore a mask that entirely covered her face and refused to speak, a pointed criticism of the silencing of women within the club. The Fluxus artist Al Hansen later recounted that the audience began chanting and demanding the mask’s removal: “When the noise got deafening, Marisol undid the strings. The mask slipped off to reveal her face, made up exactly like it. What a stunt! It’s something only she would think of and it brought down the house.”

Marisol was lauded as the rising woman artist of her generation, more specifically proclaimed the “first girl artist with glamour” by Andy Warhol for her fashion sense and the “Latin Garbo” for her apparent exoticism and famed silences. Despite this, and the fact that her name was inseparable from Pop art tendencies in the popular press and public eye, art critics tended to exclude her from most conversations about the emerging movement. Throughout the crucial years for Pop’s critical definition in the 1960s, emphasis on Marisol’s femininity, her handmade objects, and her humour were used to separate her from critiques of the canon of Pop artists who were invariably white men. Indeed, her work was used by several critics as a foil to help them differentiate between what Pop was (mass-produced, commercial, deadpan and implicitly male) and what it was not (Marisol).

In 1968, Marisol represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale and was one of only four women among the 149 artists selected for that year’s Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany. She was growing increasingly frustrated by the brutal police response to Vietnam War protests in the United States and despite her success, spent much of the second half of 1968 travelling in India, Nepal, Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. In 1969, she dedicated months to learning to scuba dive in Tahiti. Her sculpture was largely transformed as a result of these experiences.

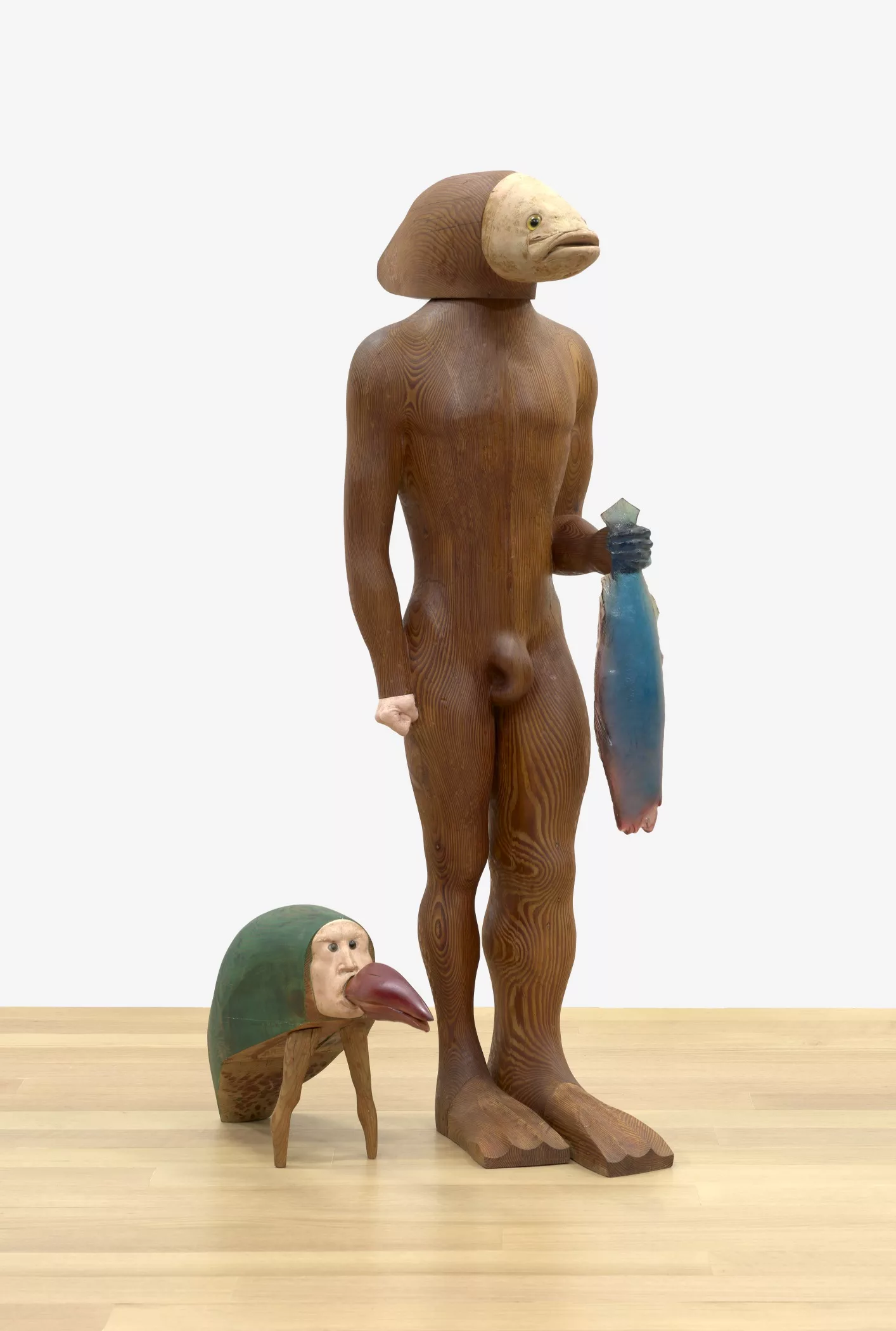

In 1973, Marisol debuted the result of her engagement with marine life in a solo show at Sidney Janis. As she later told an interviewer: “I have always had a special communication with the world of animals. I wish humans were like that.” In these new works, she explored human-animal interdependence as well as connections between the American military-industrial complex and the life of the oceans. These include the chimera-like Fishman, her iconic human-fish hybrid, and her sculptures of barracuda and needlefish, which she connected to missiles and other modern forms of weaponry. In a 1970s-era notebook, she wrote about her love of diving, but also her deep dismay regarding the rapid changes affecting the ecosystem, a concern triggered “maybe from seeing the sea at Cozumel that gave me so much life dying”, including significant damage to the coral reefs that had so inspired her. Her sadness over this was a reason why she eventually stopped diving altogether. At a time in the twenty-first century when we ignore at our peril the interconnectedness of life above and below the oceans—from the destruction of rising sea levels, to the devastation of ocean warming and acidification and the mass die-off of animal species as a direct result of human action and, increasingly, inaction in the face of climate change—Marisol’s wholehearted foregrounding of and self-identification with threatened marine species in her sculptures of this period feel prescient and inescapably relevant. In 1973, when Cindy Nemser remarked on how different these works were from the sculptures that made her reputation, Marisol contended that after her travels and her time underwater, “I am not working for the general public any more … I lost interest.”

John Perreault wrote a particularly damning review in the Village Voice in which he reassessed Marisol’s 1960s works in light of the new show, described her “neo-sophisticated appropriation of folk-art forms”, and concluded that she suffered from a lack of agency: “Marisol has been packaged and allowed herself to be packaged … I suspect she has been trapped by her face.” Among her papers is a handwritten draft that seems likely to have been written as a response to Perreault. Interestingly, she focuses on his use of the term “folk”: “If you call my work folk art it is only because you are prejudiced about my South American background, Folk you.”

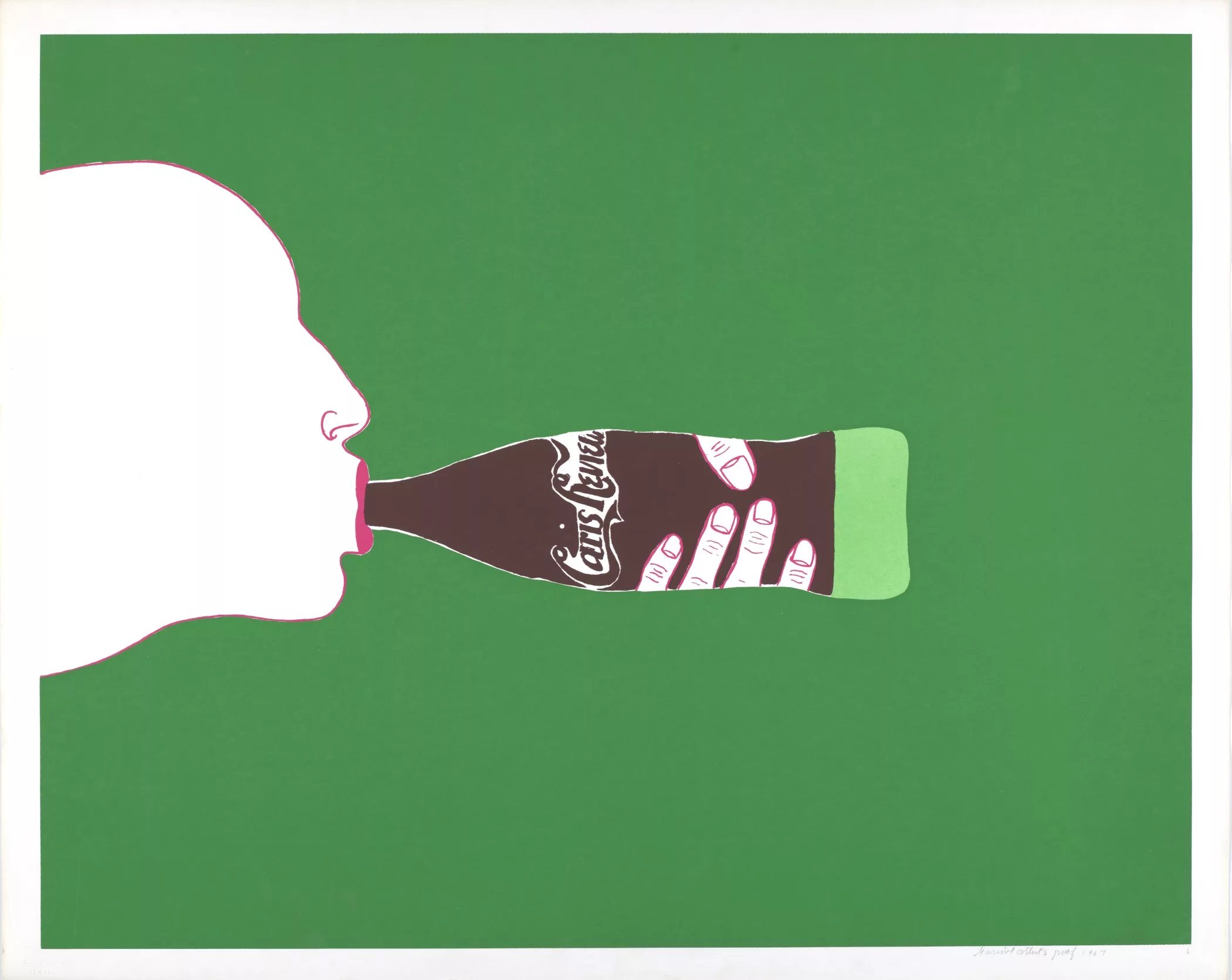

In 1975, Marisol debuted new, often anxiety-provoking, face casts and large-scale drawings that resonated with many topics being debated within the feminist movement, including gender and eroticism, pregnancy, the objectification of women’s bodies, and interpersonal violence. (Marisol, M. Marisol, 1975) In some works, she parodied the gendered signs that society takes as legible and stable, figuring a fluidity of gender expression and chipping away at perceptions of a stable and binary system of gender. Her drawings often featured body tracings as well as fragments of text sourced from personal confessions and overheard conversations. Her sculptural wall hangings feature face casts hung with Coke bottles, beer cans and other objects whose imprints can be read on the faces above. Many of these often disquieting works imply that humans are porous containers of fragmentary and shifting, rather than fixed and resolved, identities.

In the late 1970s she embarked on a new series, this time depicting late-in-life creative figures such as Marcel Duchamp, Martha Graham, William Burroughs, Georgia O’Keeffe and Virgil Thompson, who played a significant role in her own development as an artist. Most were based on Marisol’s own photographs of the subject and her time spent with them. This was also when she began creating more public monuments depicting historical figures, including many for sites in Venezuela. From the 1970s to the 1990s, Marisol was often invited to collaborate on designing sets and costumes for some of the most prominent dance companies of the later twentieth century, including Louis Falco and the Martha Graham Dance Company.

Marisol’s last major body of work, which occupied her from the 1980s until her death, earnestly attempted to shine a light on disenfranchisement in the postcolonial era. Some works focus on individuals in former colonies suffering from scarce resources, including India, Bangladesh and Cuba. In her last decade, she experienced memory loss and was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Although her production decreased dramatically during these years, she continued to work nearly until her death in 2016.

Although Marisol’s 1960s sculptures have consistently remained on view in American museums, most often in dialogue with Pop art, as fashions changed and her own interests changed and her work became more overtly political in the 1970s, she fell largely out of favour critically and commercially in her later decades. “Marisol: The Forgotten Star of Pop Art”, announced her obituary in the Guardian in 2016.

The Buffalo AKG Art Museum (then called the Albright-Knox Art Gallery) was the first museum to buy Marisol’s work with The Generals (1961–2) in 1962. The sculpture depicts two figures on horseback, George Washington and Simón Bolívar—the ‘founding fathers’ of the United States and Venezuela—in a deeply satirical take on US and Latin American interdependence at the height of the Cold War in the years surrounding the Bay of Pigs invasion (April 1961) and the Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962). Soon afterwards, the museum included that sculpture in Mixed Media and Pop Art, a 1963 group exhibition where Marisol was a guest of honour. On her visit to Buffalo, she donned a smock and touched up some paint damage to the sculpture before the opening dinner. Buffalo purchased another work, Baby Girl (1963) from her next gallery show. Both The Generals and this monstrous ten-foot-tall infant were regularly on view in Buffalo throughout the decades. But it was still a surprise when, years before her death, Marisol decided to bequeath the entirety of her estate to the museum, including approximately 50 sculptures, at least 500 works on paper, and thousands of photographs and slides as well as her papers, her copyright and her studio.

Through the assessment of this body of work, it became clear that a significant portion of Marisol’s creative achievement remains unknown to the general public or even to specialists, including, for example, her extraordinarily varied drawing practice and her engagement with the world of performance and public art. In comparison with other artists who also worked in a Pop vein in the 1960s and attained celebrity as that movement ascended, she has been the subject of surprisingly little scholarly research.

It has been my honour, then, to organise the most significant survey exhibition ever dedicated to Marisol, which opened this October at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts before travelling to the Toledo Museum of Art, the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, and then the Dallas Museum of Art. With the addition of important loans, the exhibition largely draws on the artworks Marisol kept in her own collection and left to the Buffalo AKG.

It is only by looking at her work over its long arc that we are able to appreciate Marisol not just for her satirical and deceptively political sculptures, which helped define the 1960s and are beloved by museum audiences. The exhibition also unpacks the reasons why her work was not so critically or commercially favoured from the 1970s onward, arguing that those areas of her practice that largely failed to resonate with audiences in their time are also those engaged with concerns that are particularly relevant today. These include works that embody animal intelligence and allude to environmental precariousness, express feminist anger and testify to sexual violence, engage with the immigrant experience, figure postcolonial disenfranchisement, and destabilise norms of gender and sexuality.

This text has been adapted by the author from the catalogue for Marisol: A Retrospective, DelMonico Books and Buffalo AKG Art Museum, 2023. The exhibition is on view at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 7 October 2023–21 January 2024; the Toledo Museum of Art, March–June 2024; the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, July 2024–January 2025; and the Dallas Museum of Art on 23 February–6 July 2025.

Written by Cathleen Chaffee

This feature originally appeared in Elephant #49.

buy your copy here