This feature originally appeared in Spring 2018 in Issue #34 of Elephant

Before I meet the feminist pioneer Carolee Schneemann, her gallery (Hales in London) grants me a glimpse of the shiny Golden Lion that she was awarded for lifetime achievement at the 2017 Venice Biennale. When we get together a few days later, an orange feline mask with eyelashes smiles coquettishly from the table of her hotel room.

It came from “two very wonderful women friends who knew that I was not thrilled with the modern slickness, the subversion of the animal in the gift of the Golden Lion,” Schneemann, 78, explains. “It’s all modernised so that it looks like an ornament for a car, so they went out and found a more lionish thing for me to have. Sweet.”

The award is long overdue recognition of Schneemann’s groundbreaking work over the past six decades in performance, film, painting and kinetic multimedia installation. Its feline theme is especially apt as cats are central to Schneemann’s life: she has drawn inspiration from them in her art and even employed them as media.

In her experimental collage film Fuses (1964–7), for example, which features Schneemann and her then lover, the composer James Tenney having sex repeatedly in homage to unfettered, egalitarian, erotic pleasure, their cat Kitsch looks on, purring throughout.

Kitsch starred in many of Schneemann’s works during the cat’s 20-year life. Even when she died the artist used her corpse in the 1976 performance and installation Up to and Including her Limits, in which she made gestural swipes on the walls and floor while suspended naked from a tree harness in a direct response to Jackson Pollock’s action painting. Most controversially, she flirted with the taboo of bestiality in her challenging photographic series Infinity Kisses (1981–87, 1990–98), showing the artist and two successive cats passionately “deep” kissing with tongues.

Schneemann has always had cats. She pulls out an A4 folder with photos of her “brilliant and devoted” current mog, La Niña, who sleeps with her every night at home. This trip, taking in Venice, London and Frankfurt, is their longest separation yet.

She shows me some of the “artworks” the animal has created, one using cornmeal and blue jay feathers arranged on her carpet. There are also photos of gifts La Niña has brought in. The morning Donald Trump was elected president, she left a dead mole: Schneemann and I marvel at this prescience, given Trump’s blinkered nature and the investigation around his team’s Russian links, if one thinks of the other meaning of “mole” as spy.

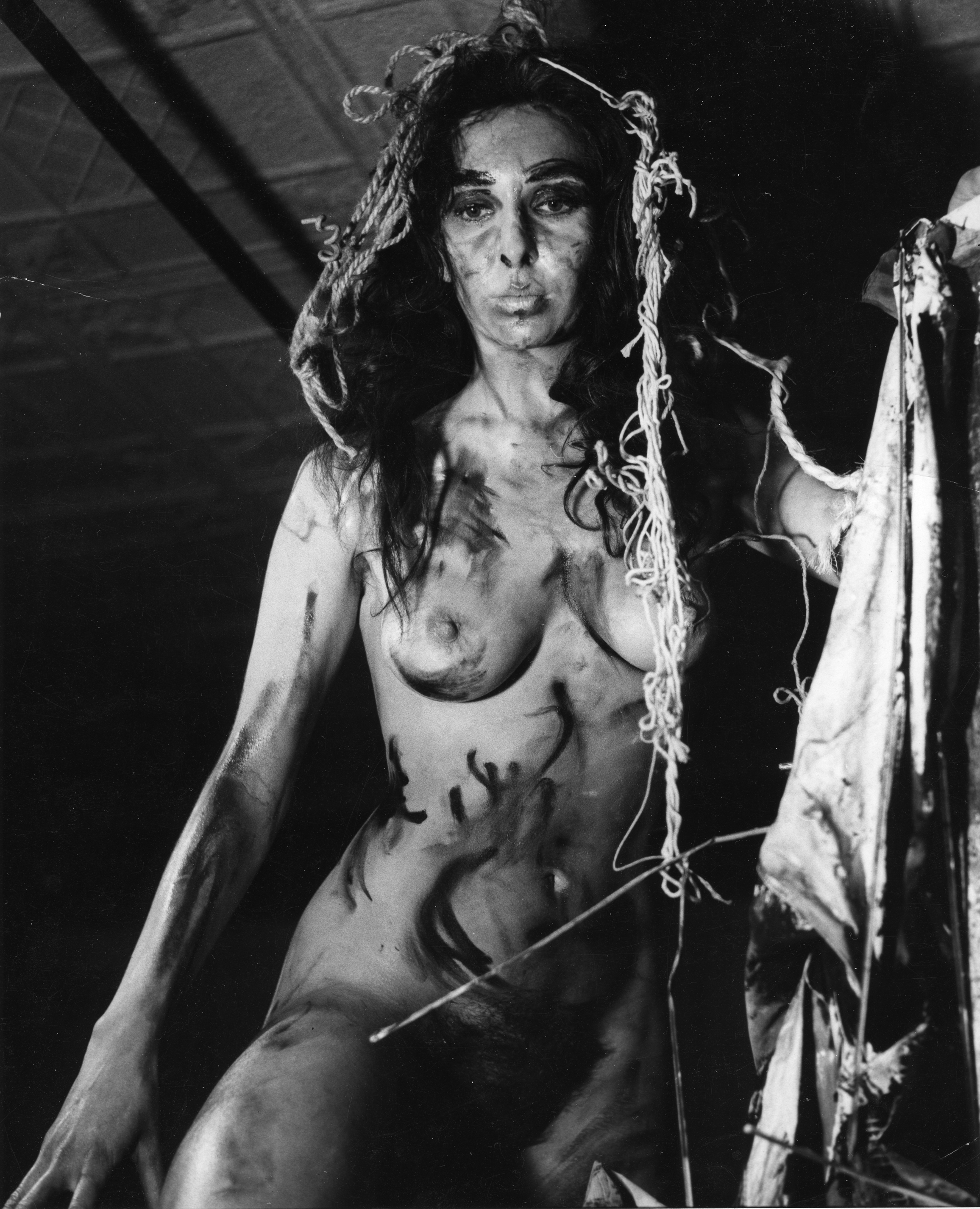

Although best known for her provocative performance works celebrating feminine sexuality, such as Meat Joy (1964) and Interior Scroll (1975), less familiar is her large body of work around disaster and destruction, which originated with her anti-Vietnam war film Viet-Flakes (1965).

“My work with disaster and war has been more suppressed than any of my work with the body and explicit sexuality,” she notes. “Your culture and mine are both based on colonialist assassination histories, and those are not what we celebrate or bring into our overt mythology, so there’s a great deal of resentment and rage when particularly a woman brings forth these images of violence.”

“My work with disaster and war has been more suppressed than any of my work with the body and explicit sexuality”

Schneemann is in London to install her show More Wrong Things at Hales before heading to the MMK Museum in Frankfurt, the second leg of a major touring retrospective that began at Salzburg’s Museum der Moderne and ends at MoMA PS1 in New York. The London exhibition is a sombre compendium of personal and public grief, focusing on three stark works. Terminal Velocity (2001–05), composed of enlarged black and white computer scans from newspapers, shows nine bodies frozen mid-fall from the Twin Towers on September 11. Her lyrical Dust Paintings (1983–88), strewn with ashes, computer chip boards, glass shards and other ephemera, were a response to the Lebanese Civil War.

The titular installation comprises a visual barrage of suffering on a mass of monitors hung at different heights: footage of corpses, a soldier shooting a prisoner, police beating protesters. These are spliced with television footage of ice skaters and race cars crashing, as well as domestic images of sexual intercourse and cats (again) eating their prey.

More Wrong Things was born out of the death of Schneemann’s beloved cat Treasure, who was hit by a car near her home in New York state. Shortly afterwards the artist unexpectedly started receiving disaster footage of bodies caught in conflict from locations as diverse as Haiti and Sarajevo.

“There were strange, almost choreographic motions, a lot of curious material,” she says. “So with my earlier footage from Lebanon and Vietnam I began to edit, starting with the images of the dead cat.” While some might consider it self-indulgent to place the death of a pet on equal footing with 9/11 and other tragedies, the work captures the surreal juxtaposition of the traumatic and mundane that characterises our daily lives.

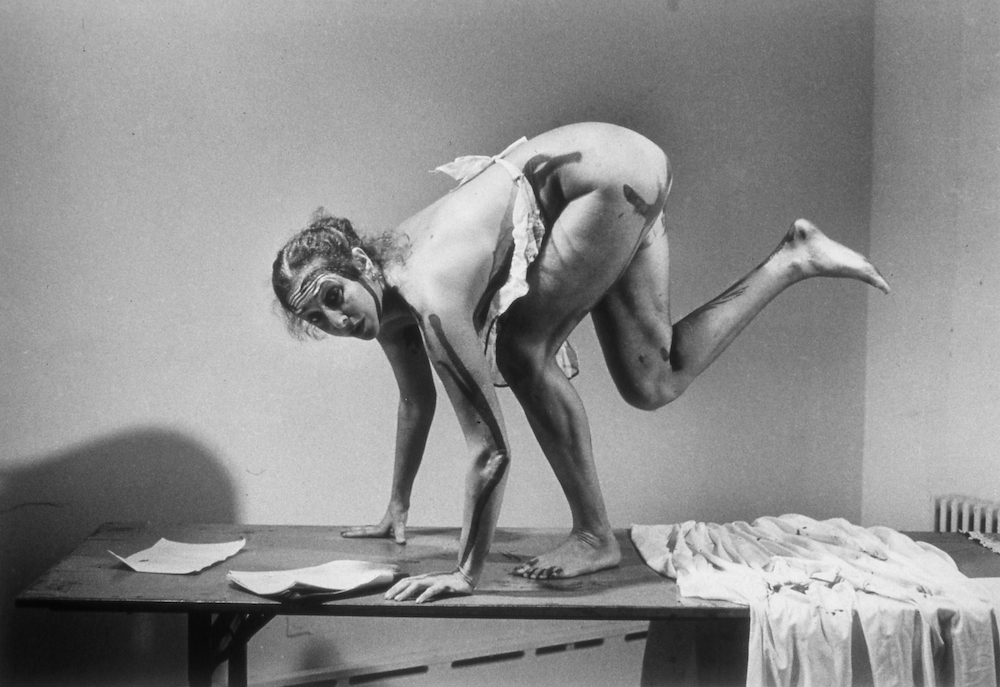

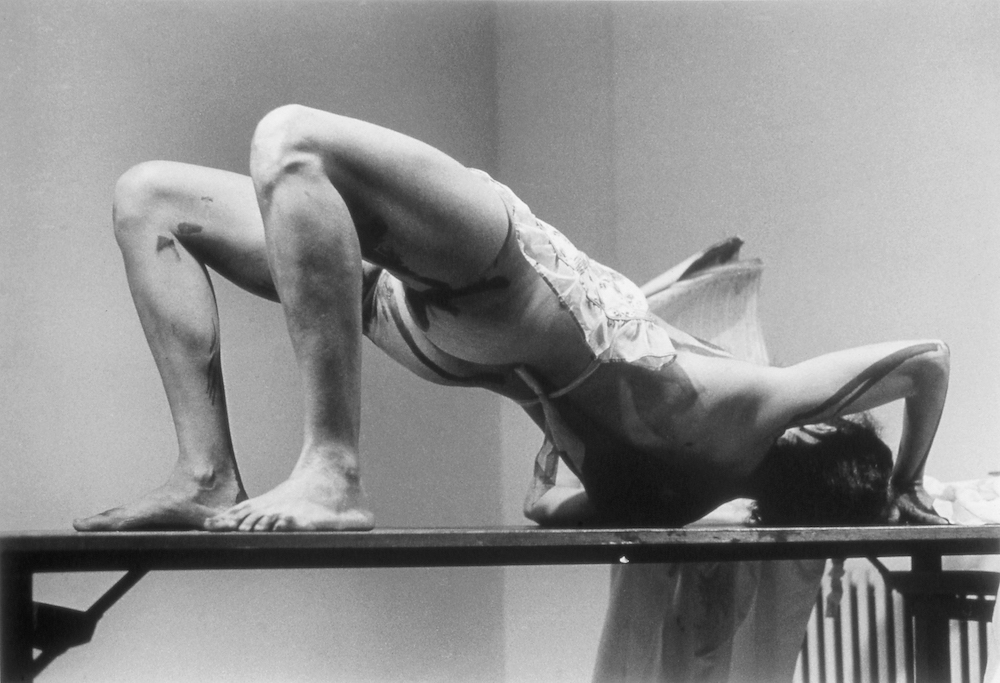

- Interior Scroll - Photo 5, 1975. Photo by Anthony McCall. Courtesy of the artist

Her latest project is centred on the conflict in Syria. “My studio is covered with images of mutilated, starved, dead Syrian men,” she declares. “When people visit me, they say how can I just sit here with all this but it’s an in memoriam for me. I felt I owed the images the presence, just the way when my animals are killed I’m very slow to bury them. The spirit is hovering and I need to absorb the transition.”

The artist doesn’t yet feel clear about her intention with the work, aware of the potential for misreadings. “I want it to be a visualisation that is unnerving and reminds people of our obligation to accept our part in who supplies the weapons, who supports this government. It is a privilege to be able to expose this atrocity and that privilege has to lead to some sense of moral responsibility,” she says.

Schneemann was born Carol Lee Schneiman in 1939 in Pennsylvania, where her father had a practice as a rural physician. Viscera and gore have been integral to her visual vocabulary since childhood.

“My mum was very repressive and conservative and full of the normal constraints and taboos, but my dad let me look at his anatomy books and travel in the car with him when he went to see patients,” she says. Her sense of body freedom, so remarkable in our puritanical Anglo-Saxon culture, is also rooted in that formative experience.

She became conscious of the limitations of the patriarchal system early on. Her desire to become an artist met with strong resistance, first at home, then in the male-dominated art world, where she battled constantly for equal acknowledgment. In her late teens she adopted the surname Schneemann: “I needed a big heavy name to be an artist.” As an art student at Bard College, she was discouraged from writing about female authors such as Virginia Woolf, who was labelled “a trivializer”.

“Your culture and mine are both based on colonialist assassination histories, and those are not what we celebrate”

The influence of the abstract expressionists is evident in her early landscapes and portraits, but she quickly became interested in expanding painting beyond the confines of the canvas. Her assemblages from the early 1960s, incorporating everything from fur and bottles to motorised elements, share affinities with Robert Rauschenberg’s “combines” and Joseph Cornell’s boxes, both artists she knew from the avant-garde downtown New York scene. Her breakthrough came in 1963 with Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, when she began using her body as a medium. “I wanted to be both image and image maker,” she explains.

An important negative catalyst for Schneemann was the erotically passive presentation of the female body by male artists such as Hans Bellmer with his contorted dolls and Balthus with his suggestive paintings of prepubescent girls. Yves Klein used naked women as paintbrushes for his Anthropométries performances, but he was always the one directing. “All of which influenced me to feel more visceral,” she remarks, “and to wonder what a lived presentation of physicality as I experienced it would look like. I didn’t know.”

For Eye Body Schneemann had her friend, the Icelandic artist Erró, take a sequence of photographs of her nude, covered in pigment, grease and chalk in her studio, interacting with her painted constructions and props such as live snakes and cow skulls. Her body was treated as just another material in the assemblage yet her living flesh introduced a primal energy to the whole.

However, critics were unimpressed and told her, “If you want to paint, put your clothes on and get in the studio.” Others branded her narcissistic and exhibitionist.

An obstacle in Schneemann’s struggle to be taken seriously has been her stunning physique and looks. At a time when feminists were addressing the problem of the exploitative male gaze, Schneemann’s insistent flaunting of her naked beauty was widely denounced as pandering to male erotic fantasies. “There was no premise for feminist pleasure, explicit erotic heterosexual pleasure,” she says.

“She and Joan Semmel were among the first women that owned sexual production, which was unheard of,” agrees the artist Marilyn Minter, whose work explores desire and the feminine body. “Usually we’ve been the object but they permitted sexual imagery as producers. That always impressed the hell out of me. That was a big step.”

“There’s a great deal of resentment and rage when particularly a woman brings forth these images of violence”

Undeterred by the dismissive reactions to Eye Body, Schneemann created Meat Joy, an orgiastic revelry of male and female flesh in which performers smeared each other with paint and writhed ecstatically among sausages, raw fish and chicken carcasses.

I make the mistake of describing that work (so different from what had gone before in its presentation of active, unbridled female sensuality) as “seminal” and Schneemann rightly pulls me up. “Seminal is such a funny word. It means ‘spermy’.” We grapple for more appropriate alternatives. “Eggy?” she suggests. “Ovaryish? No, we don’t do that, it doesn’t work. Maybe someday,” she smiles ruefully.

Both Meat Joy and Interior Scroll, in which Schneemann pulled from her vagina a roll of paper while reading a feminist monologue written upon it, originated from dreams and from the artist’s kinetic painting.

“It all came out of the stroke, the mark, collage, the tear, the rip, the positioning of visual elements as active events,” she says. “I didn’t think of them as being important. They were just images that I had to physicalise. It took a very long time for them to have some cultural presence.”

These radical works were met at the time with shock, annoyance, confusion and outrage. Yet it’s hard to overstate the influence Schneemann’s performative pieces have had on younger artists. Tracey Emin’s three-week-long naked performance at a Swedish gallery in 1996, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, would have been unthinkable without Schneemann, as would Matthew Barney’s Drawing Restraint II (1988), where he produced graphite images on his studio walls, suspended in a moving harness.

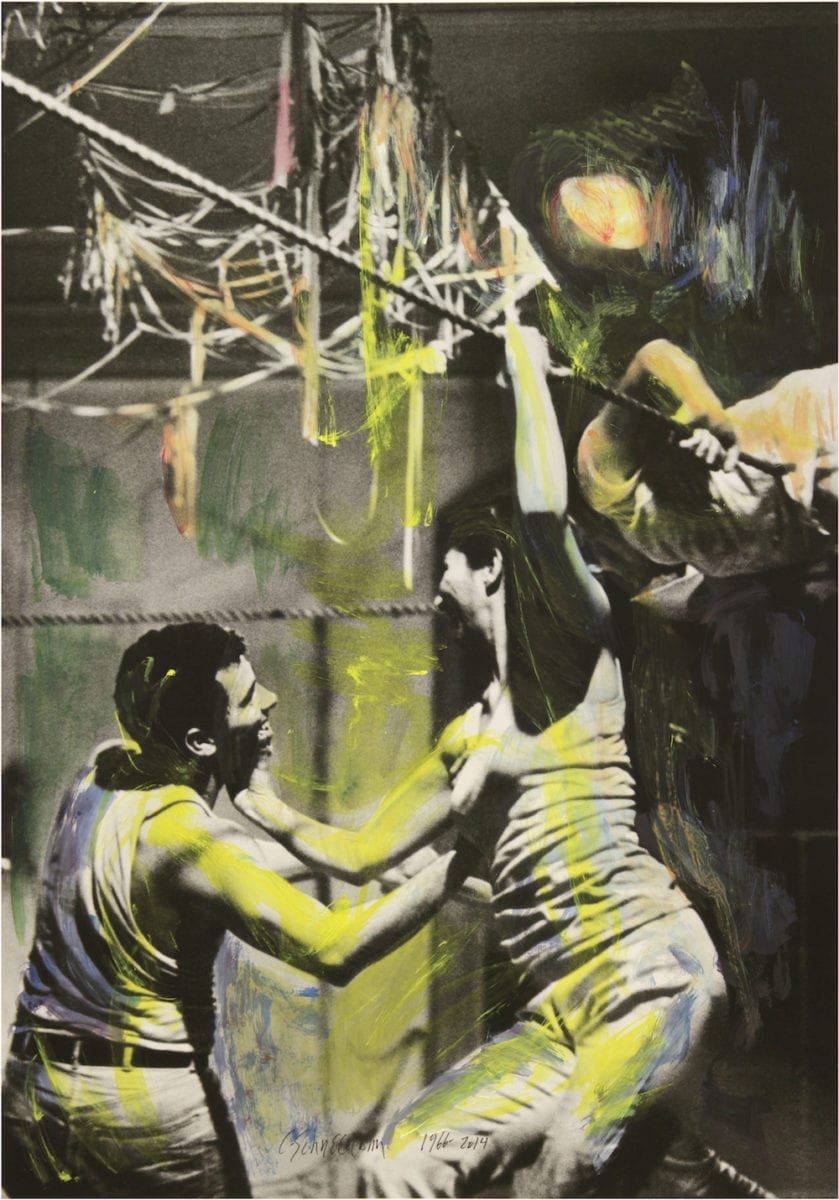

- Water Light Water Needle, 1966-2014

It irks Schneemann that she and female peers such as Hannah Wilke and Charlotte Moorman, who worked with their bodies, became defined as performance artists. “Any fucking thing now is called performance art, really anything,” she laments.

Male counterparts who orchestrated happenings, such as Red Grooms, Robert Whitman and Jim Dine, on the other hand, continued to be viewed as sculptors and painters. “It’s hard to have people understand that women were hugely significant but they had no importance,” she says of the 1960s and 1970s scene.

Still, it was a wild and heady time and she was in the thick of it. Artists from all over America and abroad converged in New York. If Rauschenberg sold a work he would throw a dinner, as sales were a rare occurrence for artists in those days.

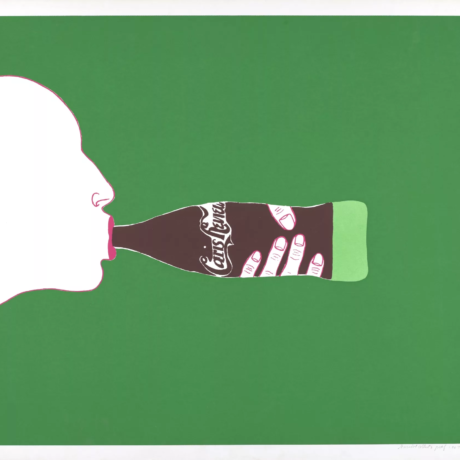

Everyone made ends meet doing weird jobs. Schneemann worked as a dog drier in a pet shop, an extra in porn films and a life model. She choreographed productions for the influential Judson Dance Theater and participated in Claes Oldenburg’s Store Days and Andy Warhol’s Factory, among many other collaborations.

She acknowledges that tremendous progress has been made in women’s art and “istory”, her term for a gender-neutral history, but worries that it’s in jeopardy from the current political situation: “The suppressors are once again in control of everything… women’s rights are once again denied, suppressed, denigrated, made obscene.”

Schneemann appreciates the belated plaudits after years of neglect, but one senses that a Golden Lion is not about to turn her head now. Our encounter ends on a melancholy note, reflecting the many “wrong things” of our times.

“The world as I wish it to be is crumbling and shattering, and in my age group my contemporaries are dying left and right,” she says. “So all these young people are all excited and ‘aren’t you thrilled and isn’t this wonderful and we’re so proud, and look what you’ve done’. All right, okay, okay, okay. I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

This feature originally appeared in Spring 2018 in Issue #34 of Elephant

Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics is at the Barbican, London, from 8 September to 8 January 2023

![Carloee Schneemann, Water Light Water Needle V, 1966-2014, painted photograph, 104 x 68.3 cm [Photograph by Charlotte Victoria]](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Carloee-Schneemann-Water-Light-Water-Needle-V-1966-2014-painted-photograph-104-x-68.3-cm-Photograph-by-Charlotte-Victoria-787x1200.jpg)