“One of the things that has not been decolonized properly is knowledge production,” explains Omar Berrada to a group of international journalists. “That is to say that we, in the global south, still look at ourselves through lenses: categories that were imposed by the outside and usually invented in the colonial period.” Berrada is the director of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair’s Forum programme, Always Decolonize! He is also a writer, curator and co-director of Dar al-Ma’mûn, an arts centre and library just outside of Marrakech. His programme began as 1:54 put on its fifth London edition and fourth New York edition, and director Touria El Glaoui returned the fair to the continent for the first time.

- Installation image of Africa Is No Island at MACAAL. Image: Saad Alami

Coinciding with 1:54 this year was the opening of Africa Is No Island: 10 Years of Afrique in Visu, at the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL), for which I was in the city on a press trip. And it is this spirit of decolonization that weaves its way through both events. The exhibition brings together forty artists from the last ten years on the online photography platform Afrique in Visu that has been a “‘visual territory’ that bypasses the very notion of borders” since its conception in 2006. The building is what Othman Lazraq, the president of the museum and the son of real estate businessman Alami Lazraq, on whose art collection the museum is founded, calls a “human-sized museum”. Its ground floor certainly feels welcoming: a maze of smaller rooms, archways and passages.

Walking through Africa Is No Island I am immediately struck by Walid Layadi-Marfouk’s richly coloured cinematic photography. “After moving to the US for school I realized there was this big divide between the representation of my culture, or of Arab and Muslim cultures in general there, and my own internal representation of my identity—probably a bit surreal, distorted by my imagination.” His project Riad is a far cry from the visual tropes that he argues dominate mainstream western media’s visual representation of Arabic cultures: deserts, ruins, overall scenes of pain, violence, misery and starvation, and often set in sombre black and white. “I’m not attacking [this kind of imagery] directly, there’s nothing in this image that says ‘This is a cliché, I’m correcting it,’ I’m just trying to bring diversity to the conversation,” he explains. Layadi-Marfouk began taking photographs when he started at Princeton University, where he had originally applied to be a mathematics major. He ended up also taking an analogue photography class and began to use a four by five camera. “I’ve never used a digital camera,” he laughs, “or even a 35mm.” One of his more Lynchian photographs features his red-haired aunt in a sparkling blue gown, arms thrown wide to the empty cinema in which he spent much of his childhood watching movies. “I could not envision talking about Morocco and my family without colour,” Layadi-Marfouk says of the dazzling reds, blues and yellows in his work. “It would not have made sense whatsoever.”

- Maïmouna Guerresi, (Left) Throne in White, (Right) Throne in Black, 2016. © Maïmouna Guerresi and Mariane Ibrahim Gallery

In Maïmouna Guerresi’s work the mystical power of belief, particularly in Islam, is foregrounded. Her double portrait Giants hangs high on the wall, forcing the viewer to reckon with it from below. Italo-Senegalese Guerresi became a Sufi when she followed her Catholic missionary uncle’s advice to visit the Catholic countries in Africa and instead found the Muslim religion in Senegal. “They’re like two guardians, it’s about the search for hope and spirituality, Muslim spirituality and the different facets of the Muslim religion, as well as the religion’s secretism,” she says.

Self-identification and status is also explored in the bold portraits of Joana Choumali’s Haabré, La Dernière Génération (The Last Generation), a project that looks at the way these concepts shift with geographical movement. The subjects of the images are men and women from Burkina Faso and Nigeria who have relocated to Abidjan in the Ivory Coast, where Choumali is based, carrying with them the scarifications that served as indicators of belonging to a certain sociocultural class or tribe, or the leftovers from an initiation rite. Yet upon arriving in Abidjan, these scarifications, once something to be proud of, became a signifier of “otherness”. Now, as these practices are dying out, Choumali has been compelled to document the individuals with whom the tradition still lives. “I was frustrated not to see it the way I thought it should be seen,” says Choumali, explaining that often imagery of Hââbré would involve very caricaturish depictions, “let these people be seen the way they are.”

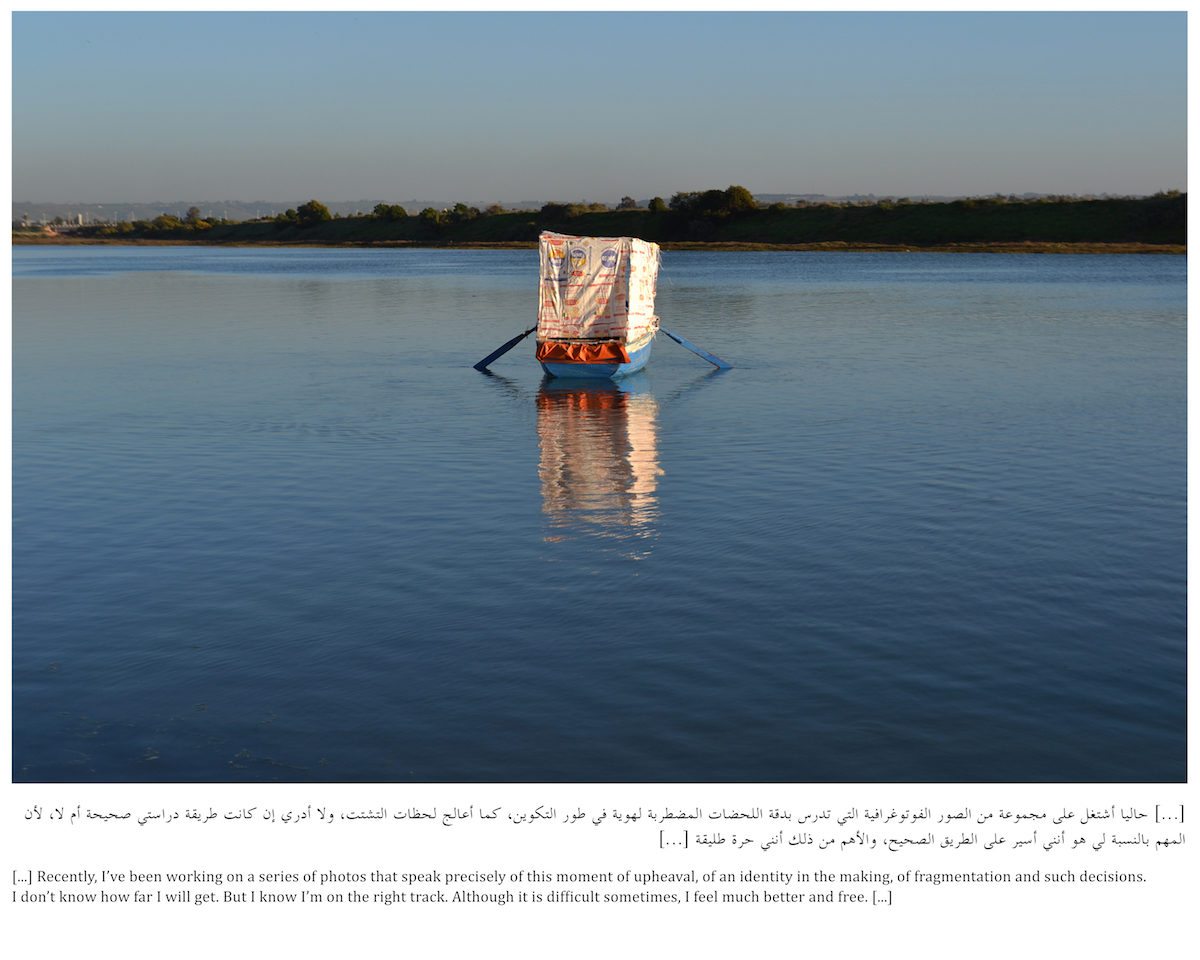

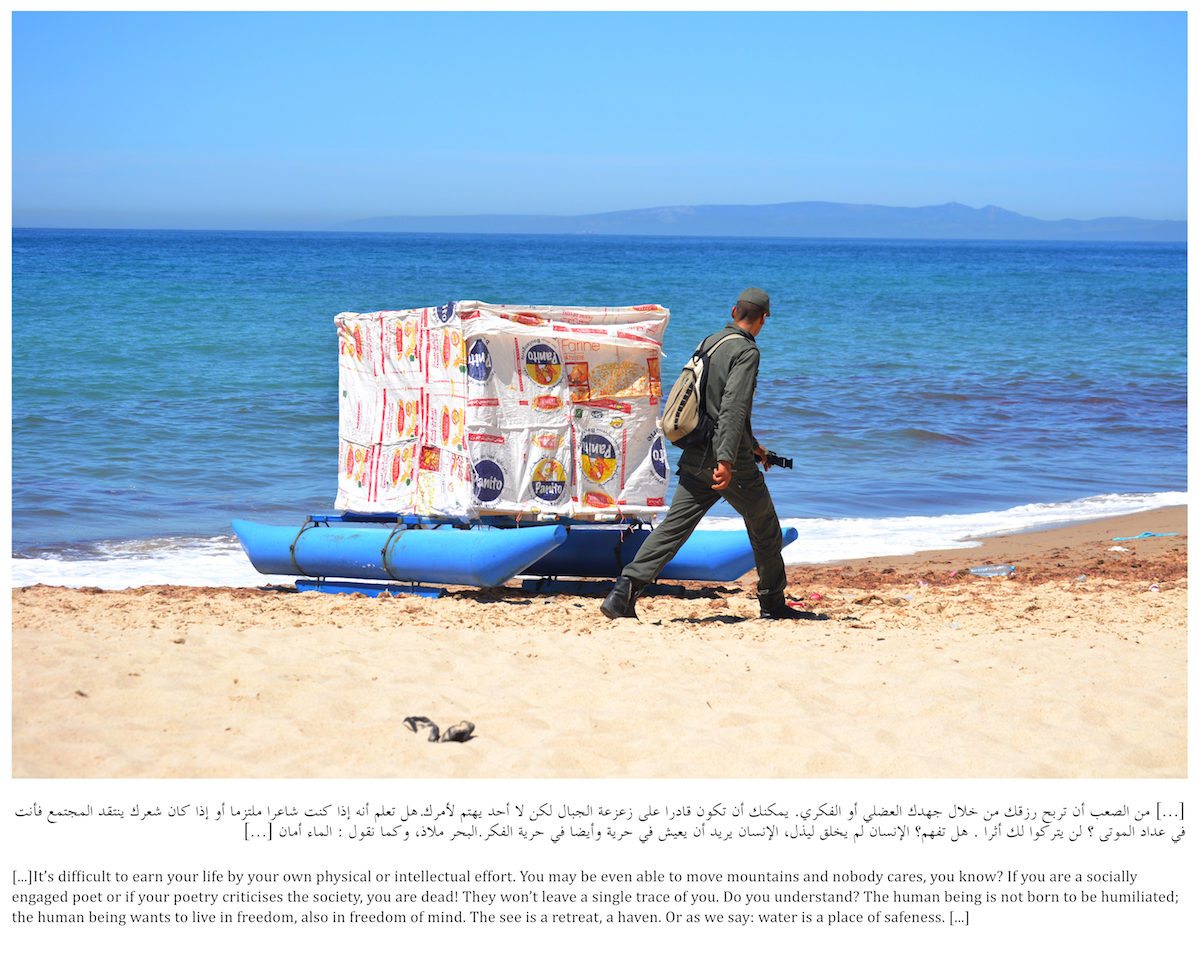

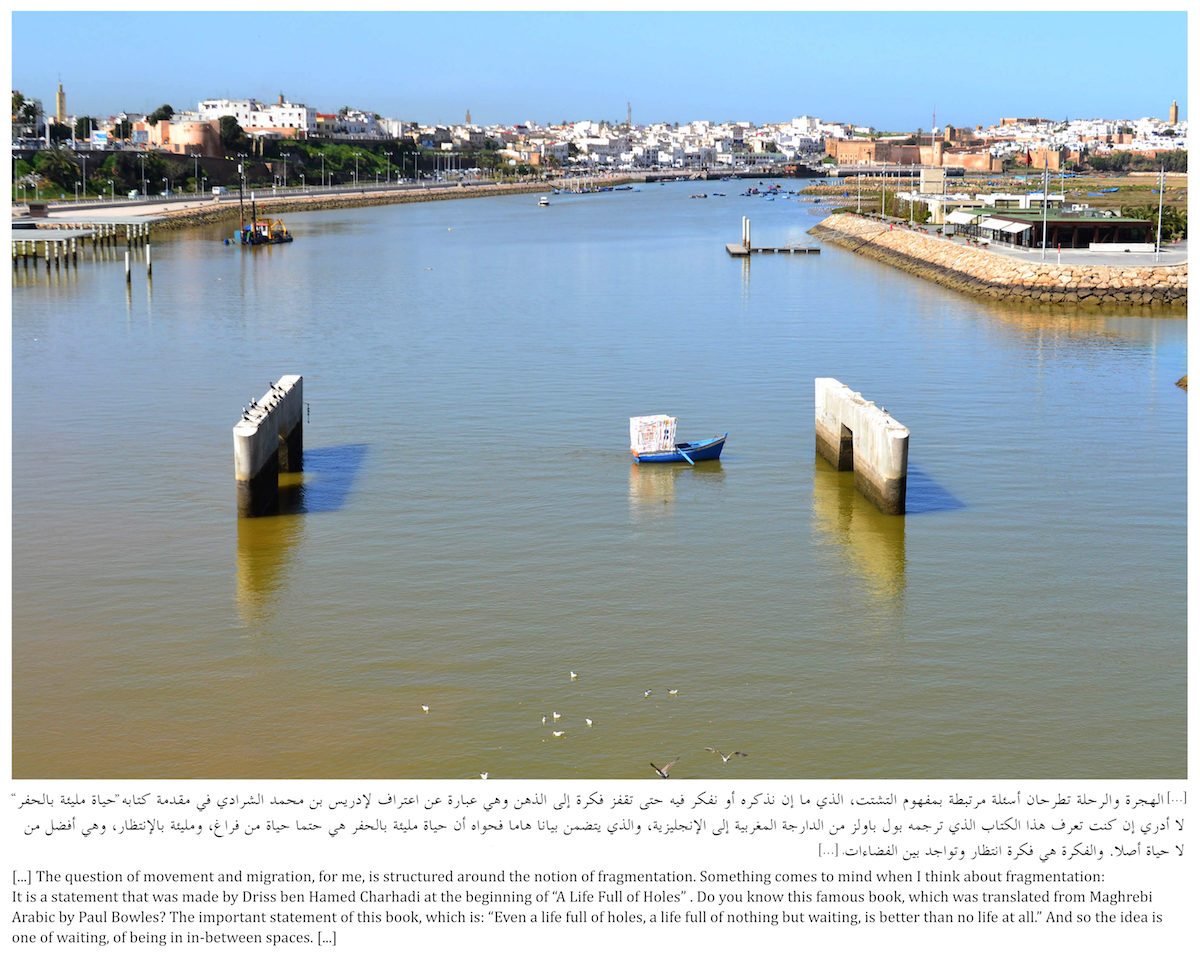

- Mohammed Laouli and Katrin Ströbel, Transit(ions) I-IV series, 2018. © Mohammed Laouli and Katrin Ströbel and Le Cube—independent Art Room, Rabat

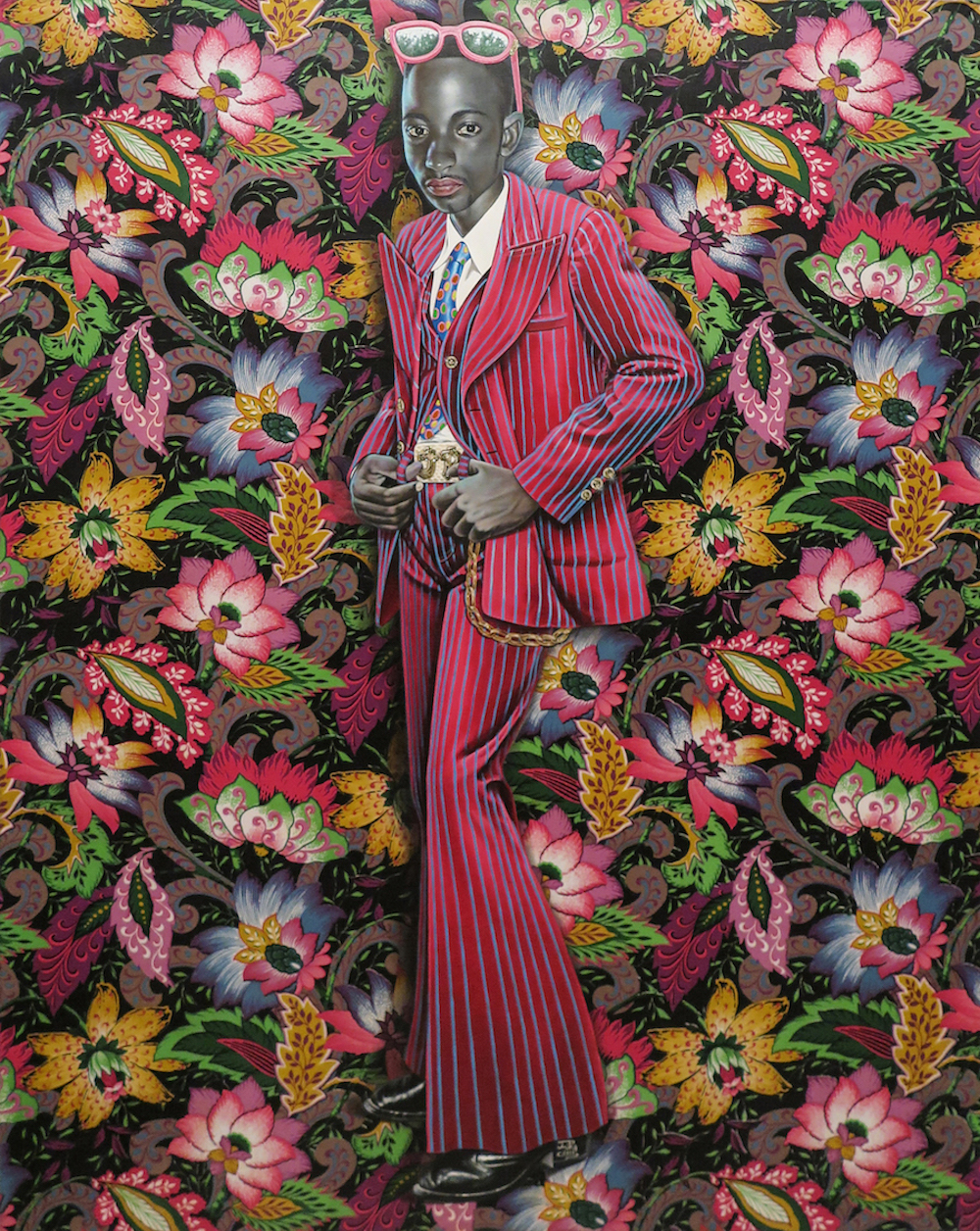

Thinking back to 1:54 I remember JP Mika’s vivid painting Elongi y Abo Muana (Figure d’Enfance), at Magnin-A: a portrait that seems to follow on from the line of portraiture set down by Malian photographer Malick Sidibe’s images of 1970s Bamako youth, some of which were also on show at Yossi Milo Gallery’s booth. The man in Mika’s painting seems young, but wary, awkward even, dressed up for the weekend yet anxious for the night ahead. As is characteristic of the Kinshasa-based artist’s work, he is painted in acrylic, straight onto a printed cloth exploding with a bright floral pattern. His pink and blue pinstripe suit is almost luminous, as if you had made eye contact with him under disco lighting and isolated him from the dancefloor he stands on.

The next evening I am caught in the crush of international visitors to Hassan Hajjaj’s Riad Yima while attending the buzzing opening of Casablanca Not the Movie, an exhibition of evocative photographs by the artist and documentary filmmaker Yoriyas, reclaiming the imagery of his Moroccan hometown from its Hollywood depictions. Glimpsing Hajjaj’s own portraiture through the crowds, I see again these celebratory colours, a mixture of references from Morocco and London, where Hajjaj spent his adolescence. Berrada’s speech comes to mind once more. “Coloniality is something that stands as a thick cloud between us and ourselves,” he explains. “We look at ourselves through this thick cloud, and decolonizing is clearing the view, achieving an undistorted view of ourselves.”

Africa Is No Island

Until 24 August 2018 at Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL), Marrakech

VISIT WEBSITE