It has been nearly two months since former president Donald Trump was unceremoniously dumped from Twitter, and slightly less since his dramatic—if lonely—exit from the White House. For photographer Matthew Morrocco, it’s a pivotal moment that mirrors Orchid, the photographic project he began immediately after the 2016 US election. “To some degree I was shell-shocked from the media frenzy of the election. The public hunger for personal information about candidates was overwhelming,” he tells me. “In 2016, we were witnessing something dystopian and it was scary. I wanted to take a step back and examine this problem.”

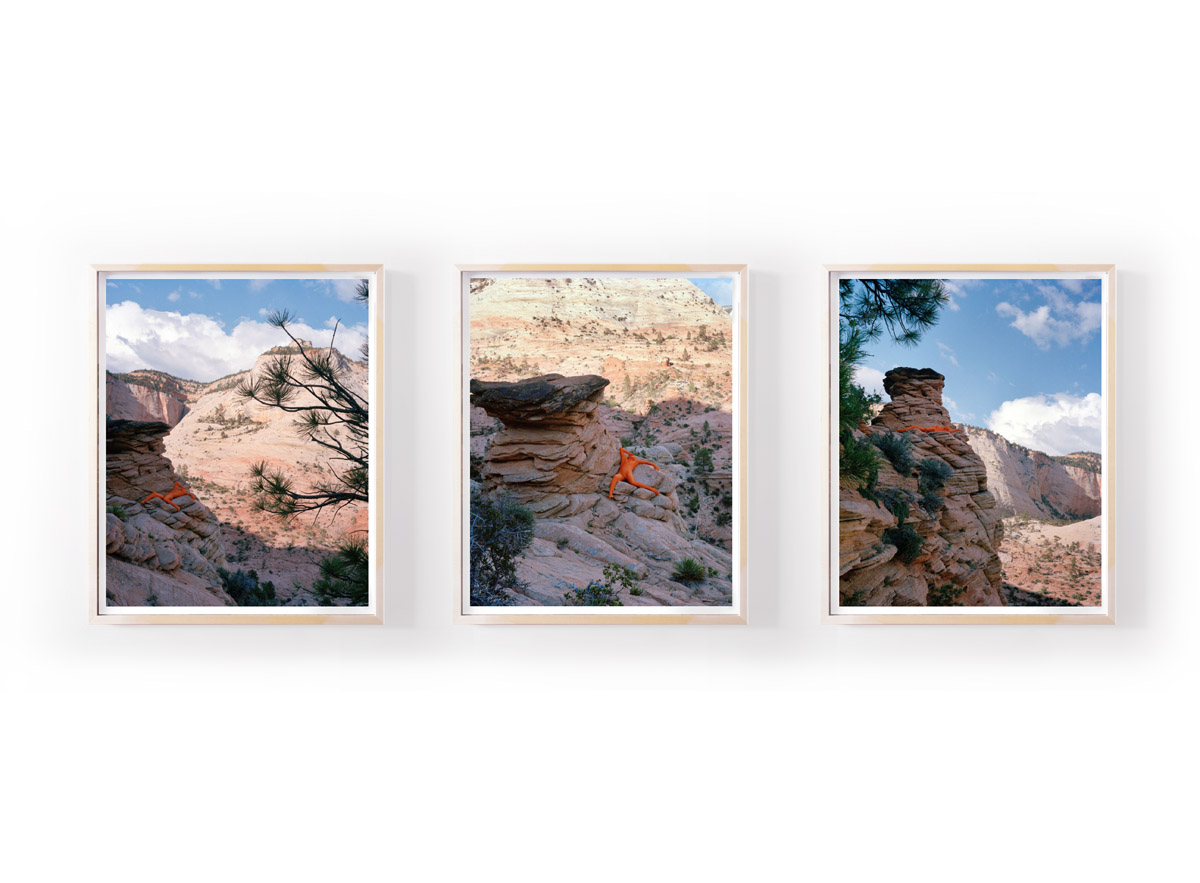

The latest iteration of the Orchid project, titled Colored to Suit, is set to launch in an online exhibition presented by RSK Artworks from 4 March, and continues Morrocco’s exploration of anonymity, social media and the role of the photograph in contemporary society. Against spectacular natural backdrops stretching from the Rockies to the Everglades, an anonymous morphsuit-clad individual performs in solitude—at once alone, yet entirely exposed and laid bare. “I wanted to draw a connection between exploitation of the natural world and exploitation of users on social media,” says the Los Angeles-based artist. “Privacy, like nature, must be protected.”

The series takes its name from The Right to Privacy, an influential essay by US Supreme Court associate justice Louis Brandeis published in Harvard Law Review in 1890. Touching on the invention of snapshot photography in 1888—when George Eastman debuted the Kodak camera—the piece examines the newfound ease with which photographs were circulating in newspapers. Brandeis argued that this form of journalism was degrading to society’s fabric—and that privacy laws were needed to counter its effects.

“The essay feels really relevant today,” Morrocco says. “Brandeis says that if we require permission from people to publish photographs of them, we will also prevent other depictions of them that are ‘colored to suit a gross and depraved imagination.’” Much like the advent of snapshot photography, the arrival of social media was heralded as a positive force intended to foster connectivity. “In the early days of social media we had this idea that the additional transparency and added social connections would enhance all of our lives,” Morrocco explains. Nearly two decades into the era of social media its sheen has worn off, with debates now raging around issues of privacy, surveillance and censorship.

Perhaps we should have predicted this: “When the snapshot camera was invented it set off a whole series of legal arguments about what privacy was in the late 19th century,” Morrocco adds. “And it is those arguments and discussions that led to some of the most important Supreme Court rulings of the 20th and 21st centuries.” For example, the right for people to access birth control, the right to abortion, and the right to have anal sex in private, all fall under a “right to privacy” that is now essentially enshrined in the American constitution.

“How do I convey that it’s possible to express an interest in having relationships with other people without sacrificing your privacy?”

Colored to Suit is a provocative visual critique of privacy within the ideals of American identity, and I wonder how Morrocco—a gay digital native—navigates social media himself. “The laws didn’t protect me in some cases from civil rights abuses by people and companies but I still lived my life as an out gay person,” he says, reflecting on the sodomy laws that still exist in some US states. “I think similarly, there aren’t laws protecting our privacy on the internet, but I still participate in that ecosystem. In general, I do my best to live an uncompromising life, but at the end of the day taking part in everyday society is important to me. I want to participate, however flawed it all may be.”

Morrocco is clearly entranced by the myth of identity—his other projects include an intimate homage to New York’s older gay community, and a series capturing the reflections of his subjects in mirrors. Photography “fell into my lap,” he explains: it was while living in Beijing in 2009 that he bought a twin-lens reflex camera for $20 that he began to use more and more. These days, he shoots with a 1950s Rolleiflex, as well as a large-format 4×5 camera. The “gravitas” of these cameras is what appeals most: “They feel so heavy and serious—it changes how people appear in front of the lens.”

“I do my best to live an uncompromising life, but at the end of the day taking part in everyday society is important to me”

The death of American artist Ellsworth Kelly in 2015 marked a turning point for Morrocco, who has studied colour theory in depth, citing the work of Agnes Martin and Josef Albers as important touchstones. German dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch is another major influence: “I was really thinking about her work a lot in this series. How do I convey that it’s possible to express an interest in having relationships with other people without sacrificing your privacy and personal space to do it?” he asks. “The figure’s free movements and anonymity, I hope, express that private moments are essential and precious.”

As a new administration settles into the White House, Morrocco intends to continue the series, albeit in an altered form. He conveys an optimism that privacy laws are moving in a positive direction, pointing to the California Consumer Privacy Act. “Whatever legal ramifications we plot out now to protect us from abuse by social media platforms will in turn help the world move toward a more equitable, grounded, and free society—in America we call it ‘a more perfect union,’” he says. “This inflection point will be hard to navigate, but it’s necessary if we’re going to safeguard so much more than just getting rid of advertisements that stalk our social media pages.”

A recent documentary by the New York Times examining Britney Spears’ ongoing conservatorship battle has sparked fresh discussions about privacy and the currency of celebrity. “Growing up in the nineties, we were exposed to these media frenzies around celebrities like Michael Jackson, Britney Spears, and OJ Simpson. There was something about that obsession with the image of these people that we all seemed to equate with power—that’s what makes social media so successful,” Morrocco says. “These days, at least for me, I feel more inclined to pursue the opposite. Perhaps real power lies in having the discipline to remain a bit more distant and unknown.”