Can you tell me a bit about Ponte City, what was your first point of contact with the building and its residents?

We met each other on a residency in 2007 and were going to do a more expansive project within which Ponte City was going to be one element. However, after we had spent more and more time in Johannesburg and the building itself, we realized how Ponte City functioned as a metonym for the social condition of the city.

The building was first intended to house luxury condos in the 1970s. How was this received, given the political landscape in the city at that time?

There was a massive demand for housing in the city in the early 1970s, as there is today. Ponte City was marketed to appeal to a very specific subsection of upwardly-mobile aspirational whites. To generalize speculatively, it would seem that this group was much more interested in their social and economic mobility than the political landscape.

“Both the good and the bad of Ponte City have become a part of the popular imagination”

It’s interesting to read the building’s original tagline: “Live in Ponte and never go out.” Do you think that wrapped up in the idea of luxury is a sense of escaping the world, not having to deal with it? It feels as though it’s a way of making oneself separate from society. Obviously given the circumstances in Johannesburg during the 1970s this is an especially troubling idea…

We’ve always been interested in how Ponte City brings together two impossible aspirational ideologies—the “city in the sky” dream of modernist architecture where everything one could need could be contained in one building, and the crazy idea that racial groups could be physically separated as a means of keeping the majority subservient. These two fallacies coalesced in Ponte City’s design and marketing, and yes, both embody the deeply troubling ideology of separation.

What is the attitude towards Ponte City right now?

It varies, like always. Some people still see it as the most dangerous building in the city, while others recognize it aspirationally from soap opera title sequences of the city skyline. It has become a tourist attraction.

In the series, it’s mentioned that the “stories of violence” but also of “seduction” which surround the place were noticed by yourselves mainly on the television screens of the various inhabitants, rather than in the space itself. How do you think television fuels our sense of longing?

The false promise of Ponte is just like the false promise of television. Both the good and the bad of Ponte City have become a part of the popular imagination, and all the myths of violence and seduction that we had heard about the building itself were not apparent in the lives of the residents, but rather in what they were watching. Television is designed to make us long for the goods and ideologies that are being sold, but also for the drama that is often absent in a working life.

What was behind your decision to photograph everything so methodically? Did this process come about early on in the project?

We read that Le Corbusier said that the apertures of a building somehow defined its essence. So we started by photographing every aperture—every door and window. It was only when we realized how many residents were covering their windows in order to watch their televisions that we added this third typology, the metaphorical window through which they look out of and beyond the building.

What does luxury mean to you?

Glam Rock; Future Slick; Global Fusion; Zen-Like; Moroccan Delight (these were the décor options for the show flats during the failed 2007/8 Ponte renovation).

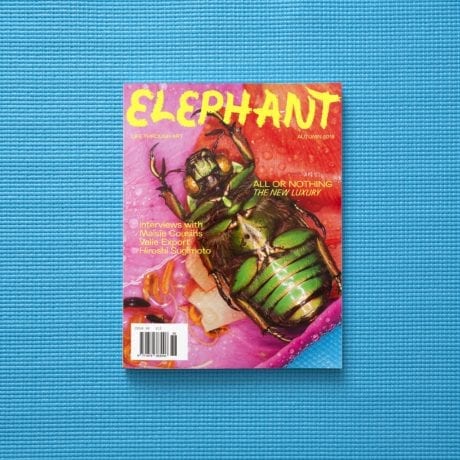

This feature originally appeared in issue 36

BUY ISSUE 36