There’s something so wonderfully ethereal about the paintings of Monica Sjöö. Lustrous greens and blues fill her canvases. Abstracted figures metamorphose into surreal shapes, both one with the earth and yet markedly distinct from it too. Divine, incorporeal, and otherworldly. While these bodies are widely depicted as Goddesses and celestial beings, there’s also an inherent universality to them. Feminism, spirituality, ecology and activism were not only central tenets of Sjöö’s work but also of her radical philosophical practice.

A Swedish-born anarchist ecofeminist, Sjöö was an artist and writer whose work intertwined activism, feminism and spirituality. It’s precisely this intransigent dedication to feminist social causes that recur throughout her oeuvre, as seen in Back Street Abortion – Women Seeking Freedom from Oppression (1968), House-Wives (1973) and Our Bodies Ourselves (1974). But if the subject matter of Sjöö’s work seems ostensibly broad, that’s because her activism was, too. During her lifetime, she would demonstrate against US imperialism, the Vietnam War, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the war against Iraq, GM foods and globalisation, amongst many other causes. Co-founding Bristol Women’s Liberation in 1969, Sjöö also emerged as a key figure in the British women’s liberation movement and the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. As an activist, Sjöö’s efforts span countless files and folders in Bristol archives, each filled to the brim with articles, drafts and activist ephemera.

It’s only in recent years – and since her passing – that her contributions to feminist and spiritual art have been widely recognised by galleries and institutions. Last year the Moderna Museet in Stockholm played host to the artist’s first-ever retrospective, Monica Sjöö: The Great Cosmic Mother, now on exhibit at Modern Art Oxford. And if you go to Tate Britain’s Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970 – 1990, you’ll also find a few of Sjöö’s works there too. Her Wages for Housework (1970) depicts the Italian-based grassroots campaign of the same name, which Sjöö also participated in. At protests, the placards would often read: ‘Tremble, tremble, the witches are returning − not to be burned, but to get paid’. For an artist whose work sought to reclaim myths about womanhood and mysticism, this was fitting sloganeering. Also on display is the striking and aptly-named Phallic Culture (1970) which features a giant penis and two troops against a backdrop of brutalist buildings. Subtlety isn’t one of the painting’s strong suits, but its message is loud and clear.

Although much of Sjöö’s art was dedicated to exploring the plights of womanhood, her depictions of mothering and the maternal make for some of her most compelling, if controversial, work. While giving birth to her son in 1961, she reportedly experienced a vision of the Great Mother, a deity encompassing both dark and light, life, and the Spirit World. Birth (1964) illustrates this encounter and ‘the enormous power of my woman’s body, both painful and cosmic’. Birth unveiled at a small Bristol gallery eliciting outrage and accusations of obscenity. In her 2004 biography, Sjöö said that she ‘decided there and then that [she] would dedicate my life to creating paintings that speak of women’s lives, our history and sacredness.’

Following the birth of her first child in a hospital, Sjöö opted for a transformative natural birth at home during her second pregnancy. This decision marked a revolutionary shift for her, serving as the inspiration for the creation of her infamous painting, God Giving Birth (1968). Sjöö vividly described the experience as supernatural, feeling an extraordinary connection with the divine force of the Great Mother within her. Like Birth, Sjöö’s most infamous painting God Giving Birth (1968) was deemed so offensive to Christianity that she was nearly prosecuted following its first exhibition in 1973. Scandal and censorship only strengthened Sjöö’s resolve to create her expressive, feminist art. ‘How does one communicate women’s strength, struggle, rising up from oppression, blood, childbirth, sexuality,’ she asks in a collaborative manifesto with Anne Berg, ‘in stripes and triangles?’ For Sjöö the answer was already evident: her work needed to reflect womanhood in all its glory and all its pain.

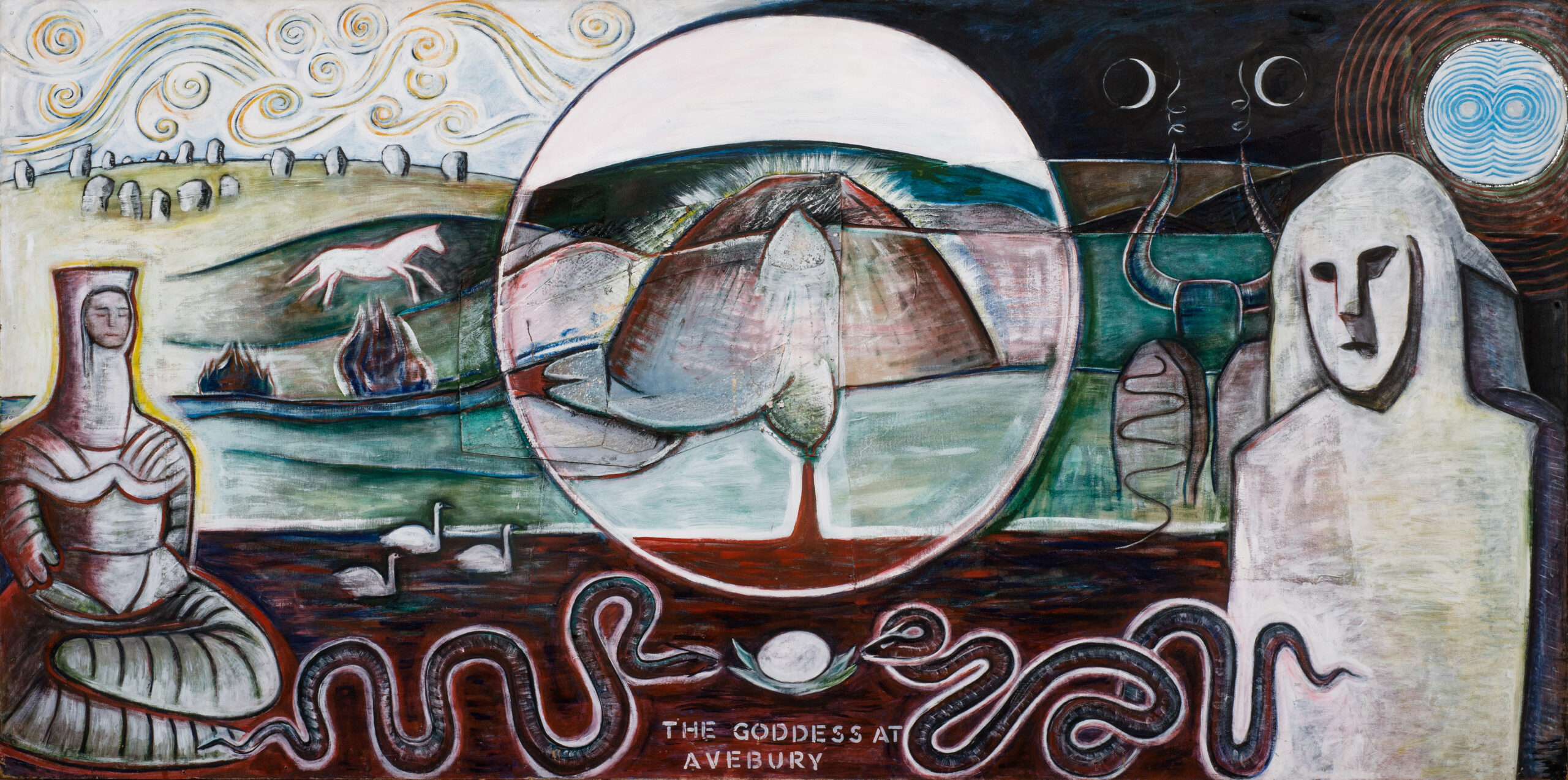

Central to her later works was a mode of spirituality that entwined Neolithic Goddess cultures and British paganism. 1978 saw Sjöö ingest psilocybin mushrooms on Silbury Hill at perimeters of Stonehenge, undergoing a psychedelic and profoundly spiritual experience while in communion with the Great Mother. It was this encounter, she claimed, that inspired her to paint The Goddess at Avebury and Silbury (1978) – an ancient landscape adorned with menstrual blood. ‘In my altered state,’ she said of the piece, ‘I travelled back thousands of years […] I experienced Her as entirely alive, a great spirit that gives us life and soul. I saw Her undulating and breathing!’

Though Sjöö had found unprecedented artistic and spiritual inspiration through the Great Mother, her creative practice briefly halted following the sudden death of two of her sons in the 1980s. Unwilling and unable to paint, the artist sunk into a deep depression. Sjöö never lost her connection with the Great Mother, though, and in her own words, says that she ‘had felt that [she] was mystically in communication with and guided in [her] painting by ancient women who perhaps, in fact, coexist with us still, in a different dimension of reality.’ In one of the few pieces she created during this period, Rebirth from the Motherpot (1986), Sjöö sought to capture that sentiment of regeneration and renewal amid the pain of her loss. Adorned with rich colours and an amalgam of animals, people, flowers, and mythological beings, Rebirth marked a shift in Sjöö’s work. Seeking comfort in landscapes, ‘she created her own support structure,’ notes Amy Budd, curator of the Modern Art Oxford show, in World of Interiors, ‘and she kept protesting.’

When Sjöö died from breast cancer in 2005, she donated most of her work to the University of Bristol’s Feminist South Archive. Within her lifetime she would also have to give away most of her extensive body of paintings as she was unable to store them within her home-turned-studio. ‘She never had regular income or work – it was hand to mouth, and her materials reflect that,’ Budd explains, noting that Sjöö often took to using materials boards and house paint instead of the standard canvases and oil paints.

That Sjöö was never formally recognised as a great artist within her own lifetime might tell us something damning about the inhospitality of the British contemporary art scene. She spent much of her career shunned from that coterie because of her radical political and spiritual activism; it’s only in the past five years, according to Budd, that there’s been an emerging critical interest in her work. Sjöö would address this inequality in her manifesto, ‘Towards a Revolutionary Feminist Art’ (1971), and collectively organise exhibitions of women artists, laying the foundations for not just the British feminist art movement but also the development of women’s art internationally.

Though her work is now on display at two major British institutions, her extensive catalogue of paintings – along with her biography – have long been available on her website. But seeing Sjöö’s art in person shows you something that just doesn’t translate into reproductions or on a screen: her use of colour. Her early works, like Mother Daughter And The Sacred Mushrooms (1972) and The young homosexual man’s dream (1966), rely on a muted palette of browns, reds, ochres and yellows, while those painted after the mid-1970s are rich with luminous earth tones. It’s a shift that marks not only her ever-deepening spirituality but also her rebirth from unfathomable loss. There’s a brightness and a light to these works – and there’s a profound hope, too.

Approach Sjöö how you will, then. Although recent exhibitions have finally recognised Sjöö’s work as a testament to her indelible role in British civil rights activism, the impact of her work extends well beyond the confines of museums and archives. It spills out onto the land she traversed in her quest for spiritual self-actualisation, the countless protests she staged, her expansive corpus of written work, and well beyond those, too. Ultimately, Sjöö believed in the transformative power of her art as activism, a tool to communicate with the past, confront oppression and think of alternative futures. Her paintings – bold and beautiful – are a testament to that very vision. We might very well join her in imagining otherwise, turning to ancient worlds to envision one anew.

Written by Katie Tobin